Joanna Zielińska: The overall image in your works is governed by very specific rules. Motifs circulate and paintings — which often have a painting-within-a-painting structure — are further reflected in sculptures and objects…

Tomasz Kowalski: There are no clear boundaries between particular pieces. I picture a situation; I decide upon a detail and crop it; singular elements are transformed into others… Sculptures work on the same basis; they are often attributes of the figures depicted in figurative paintings.

JZ: Is your work a whole?

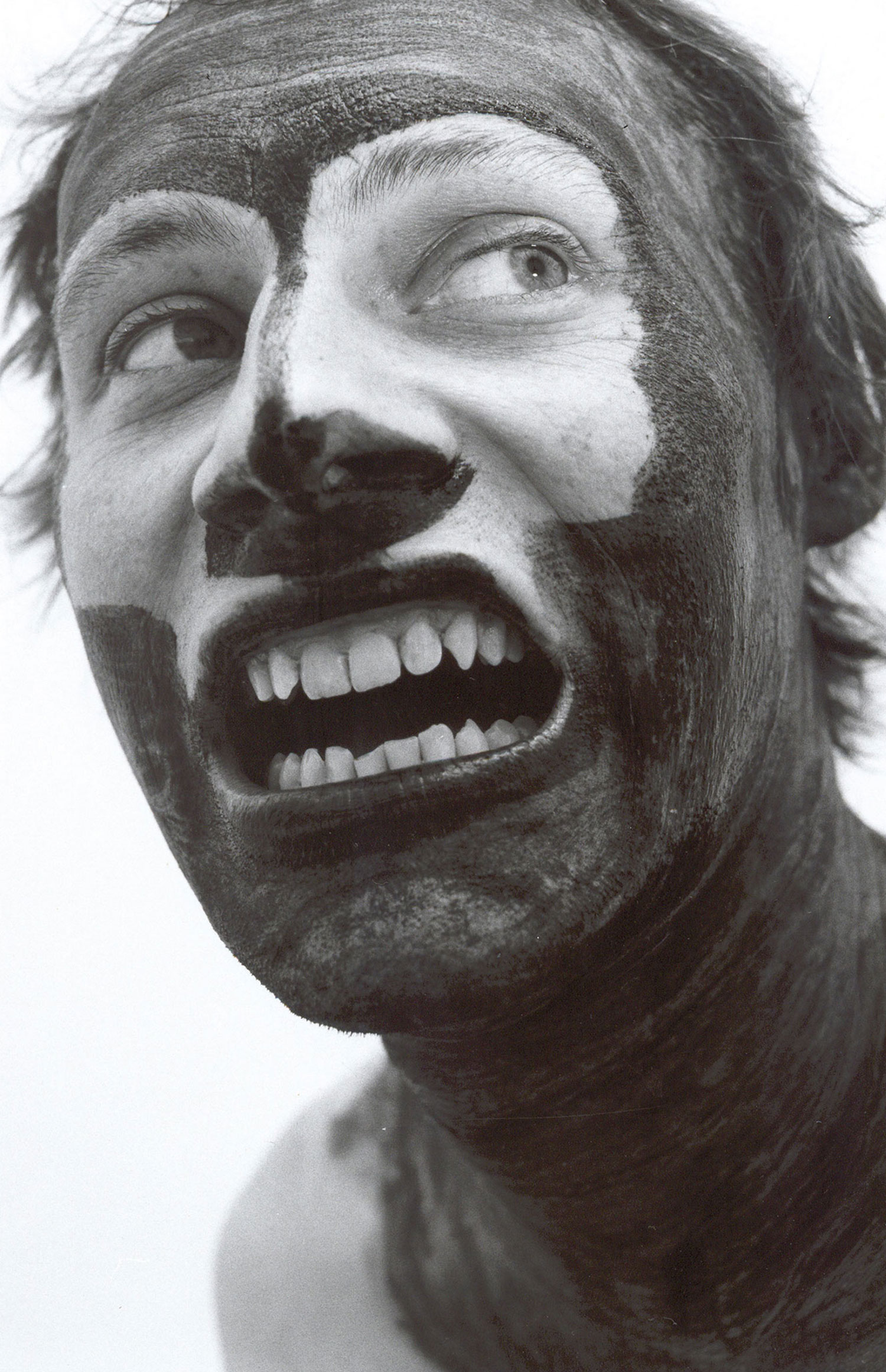

TK: It’s based on the domino effect. Some of the motifs have a huge impact and require a lot of work; it’s a whole process of accumulating reflection upon reflection, meaning upon meaning. The painting The Chimney Sweeper (2010) — which is my interpretation of Edmund Monsiel’s work — is a good example: an “Ensorian composition” featuring many masks and staring faces. These motifs focus around the figure of a chimney sweep who touches the pupil of his eye with his sooty hand. That image is reflected in other works: paintings, collages and in a radio play. It’s a psychedelic vision, an epic story that grows out of a single work.

JZ: Why a chimney sweep?

TK: I had the idea of combining different shades of black, like in the picture painted in various tones of black, black upon black. I imagined a chimney sweep, wearing his all-black uniform, who goes into a chimney in the middle of the night and touches the pupil of his eye with his dirty hand. That was the basis for my “scenery.” I chose attributes for the sweep and recorded a radio play about a chimney sweep who got lost on a church roof… anyway, the point was that different tones of black mix on the surface of a picture.

JZ: You often relate to childhood experiences. Your language is full of recurrent motifs such as, for example, a curtain, a room with a wooden floor, insects, a circus… they remind me of children’s stories.

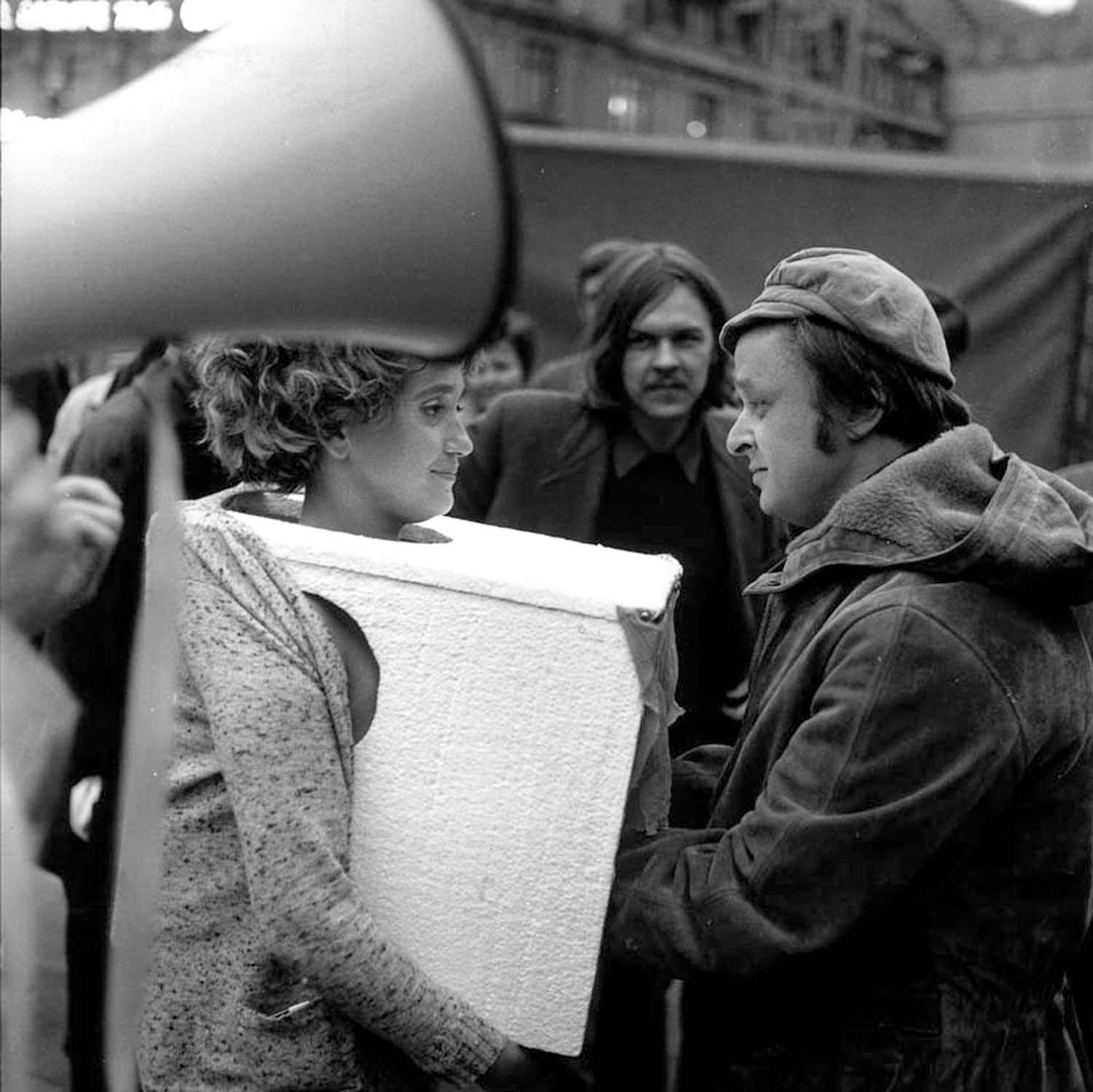

TK: The motifs you mention are directly related to the history of art. I developed that language because I needed it for my narration. I have abandoned it to some extent as my objective now is to reduce the narrative element. My ideas are still the same though. I keep working on similar themes like theater, constructing static performances that take place in my pictures. It’s all the same, all the time — no matter whether it happens on stage, in the dark, or whether there are insects involved.

JZ: What is the next step?

TK: In my new pieces I am more concerned with aesthetics and form; narration comes afterwards, bringing emotions, memories, false memories and dreamlike distortions. In that sense, the story is out of control. I make pictures out of modeling clay, partly to rest from narration. I was very intrigued by the idea of juxtaposing narrative-based works with minimalism. Someone rightly called the clay pictures “secretions born out of excess,” or “dung of narration-based paintings.”