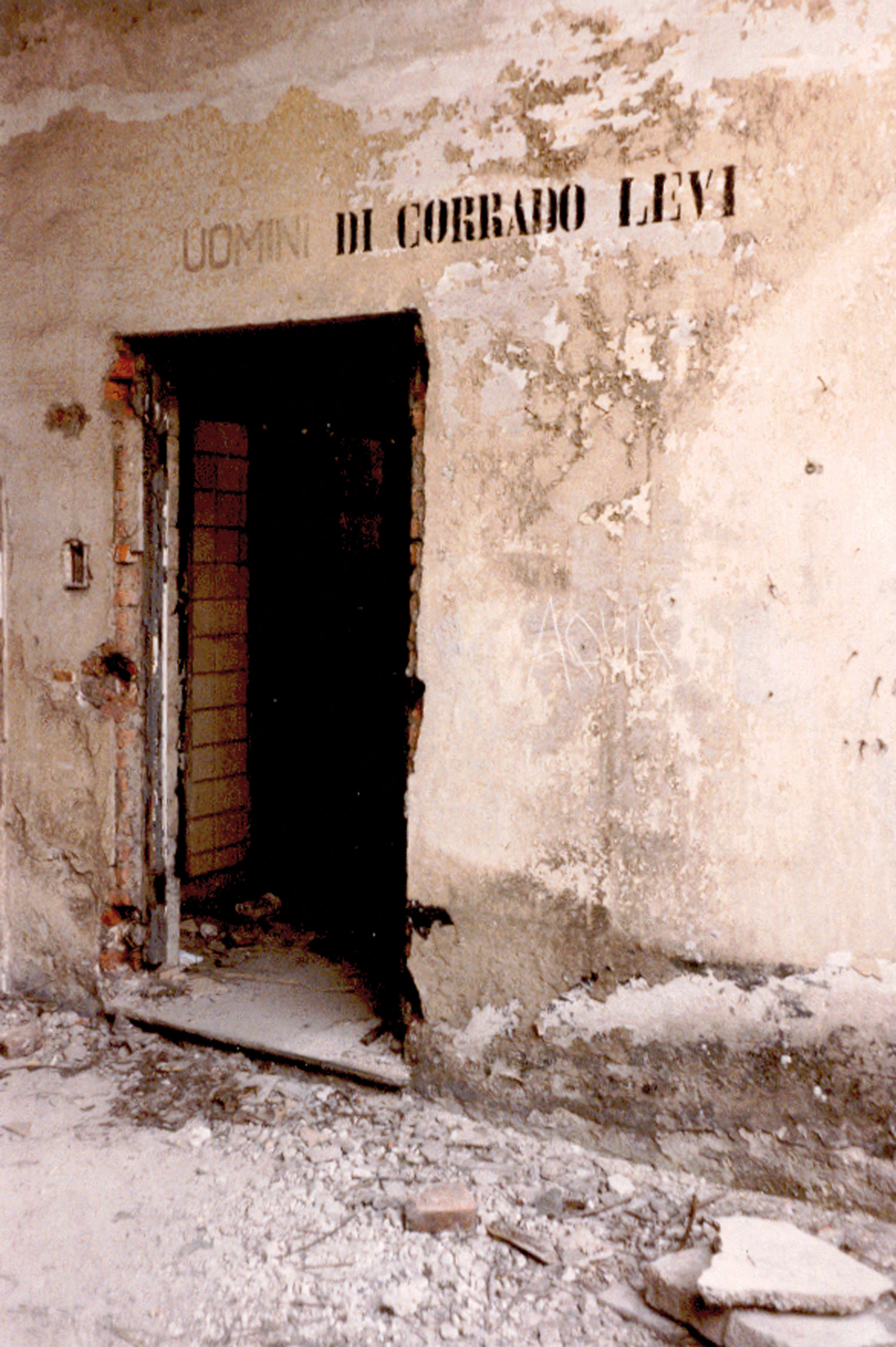

Andrei Tarkovsky shot Nostalghia in Italy in 1982, away from the USSR, a country in which he could no longer live but which he missed terribly. The title doesn’t translate as the Italian/English “nostalgia,” but as a state of perennial, site-specific ache for one’s roots, “for an inner home, some inner sense of belonging,” as he wrote. The main difference between the last generation of Italian artists (who came to fore in the early ’00s, mainly in Milan around the Accademia delle Belle Arti in Brera and the classes of Alberto Garutti and Luciano Fabro and used the galleries in Milan and Turin as global springboards) and their immediate predecessors, is that many of them not only work, but currently live abroad: Berlin, Paris, London, New York, Los Angeles, Anchorage. This exodus amplifies their being, somehow, nostalgic. Let’s take it positively, for a change, as a side-effect of the struggle to process and translate (i.e., to carry somewhere else) our entrenched genius loci and its craving for the archaic — the reference is to Pasolini, not to Neorealism (the ever-impending, black-and-white, emo cliché). It’s a work of research, re-enactment and appropriation of an eccentric tension towards modernity, which runs from the Futurists to Fontana and Manzoni, the architectures of Mollino and Scarpa, the conceptual rigor of Agnetti and Baruchello, to a series of ’70s “open practices” mixing performance, art, design, communication strategies and radical architecture — Sottsass, Global Tools, Superstudio, Gianni Pettena, Ugo La Pietra, just to name a few that should finally receive more attention; and again, besides the international glorification of Alighiero Boetti, there’s the rediscovery of fellow shaman/showman Gino De Dominicis. Let’s see how Francesco Bonami, next fall, at Pinault’s Palazzo Grassi in Venice, will reframe such intergenerational dialectics in his vision of “Italics.” But there’s more. Italy is not the only place whose younger artists seem interested in the implications of a retrospective future, but as a country plagued by amnesia and repression, this tendency gets as close as it can to bridging a cultural/memory gap, and coming to terms with history. It’s maybe not by chance that two Italian bestsellers of 2007, straightforwardly tackling taboo subjects like the mafia and terrorism, were written by Roberto Saviano and Mario Calabresi, both born in the ’70s. At the recent “Annisettanta” exhibition at the Triennale in Milan, the ghosts of the killings of Pasolini and of Prime Minister Aldo Moro, kidnapped by the Red Brigades, were evoked by two installations by Elisabetta Benassi and Francesco Arena, respectively. Andrea Salvino has now been painting his series of angry “antagonists” for a decade, while with India Hotel 870 (2007) at Fondazione Sandretto in Turin, Flavio Favelli retold the story of the bombing and disappearance at sea, near Ustica in 1980, of a DC-9 plane, an event covered-up by institutions. The past is a hard bubble to burst: in two striking, ongoing photographic series, Armin Linke portrays the obsolescence of shut-down Italian nuclear plants and the paradoxically grand, frozen headquarters of our Republic.

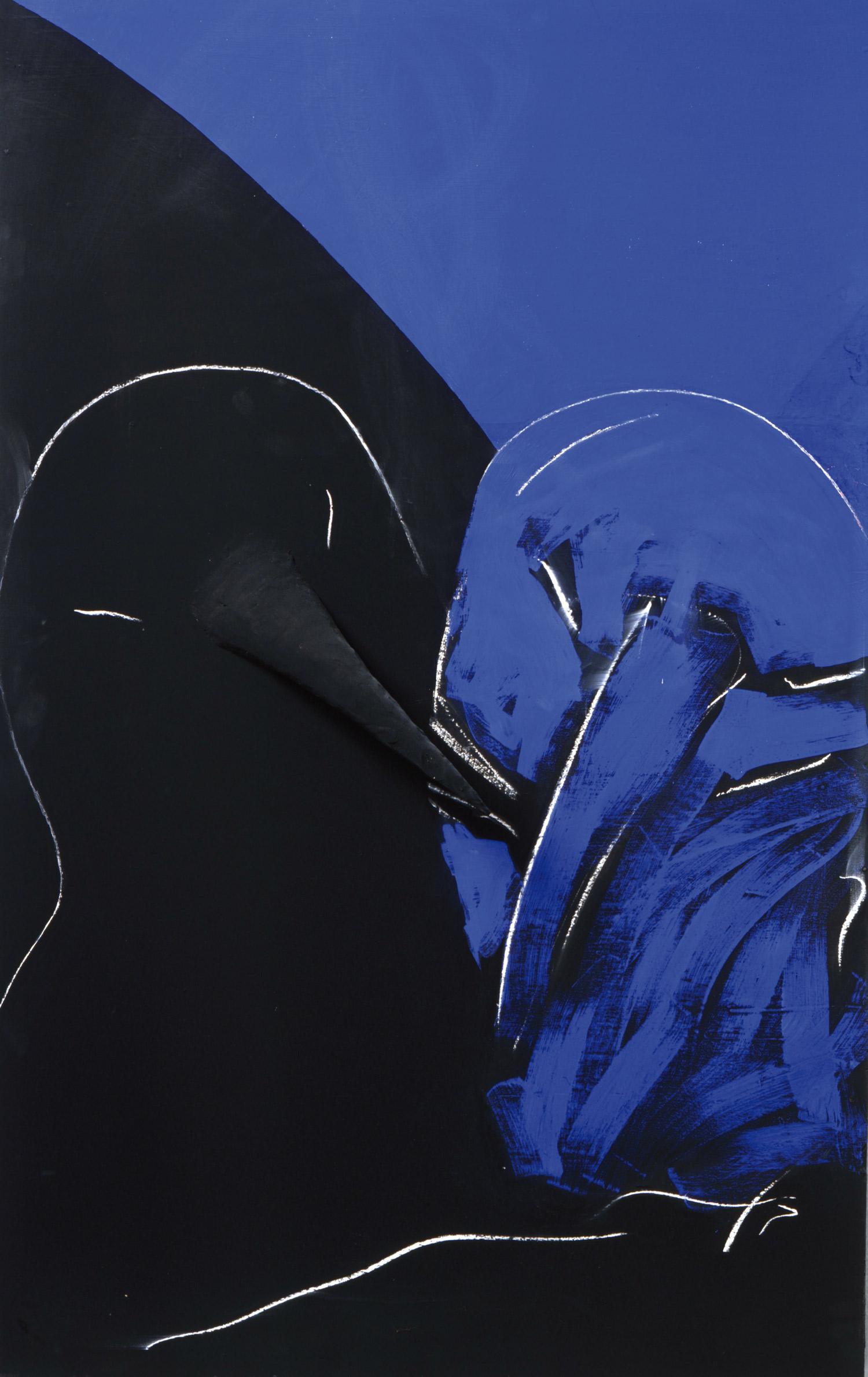

An atmosphere of enigmatic timelessness and entropy imbues the works of Pietro Roccasalva (who will be featured in the upcoming Manifesta 7 in the Trentino-South Tyrol Region, along with Previdi, Trevisani, Vascellari, Ligorio and Alterazioni Video, among others), ranging from oil painting and pastels, carried out with a painstakingly skilled technique, to carefully orchestrated performances, collage, neon, video and film. As De Dominicis referred to Sumerian myths and Urvasi, the goddess of beauty, Roccasalva calls upon Zurvan, the Persian god of time, space and destiny, ascribing him a series of “Fisime” (Whims) where images, shapes and evolutions constantly shift, migrating from one support to another. With his hermetic sculptures, large installations and photographs, Giuseppe Gabellone practices dystopia: his works pull the viewer into a dimension where the matrix is constantly missing, the elaboration of time is consuming and the feeling of alienation is often frustrating. Diego Perrone plays with distortion and the recklessness of form in a more sinister vein. For La mamma di Boccioni in ambulanza e La fusione della campana (a title inspired by Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev), his solo show at CAPC Bordeaux and MAMbo, the new, active museum of contemporary art that just opened in Bologna, he printed on hand-cut, heated sheets of forex the face of the Futurist’s mother morphed into an ambulance scene, thus turning care into scary ritual.

This imagery resurfaces in the masks of Mamuttones, archaic carnival costumes of rural Sardinia, which Perrone introduced in his sculptures exhibited this year at Casey Kaplan in New York and then at Giti Nourbakhsch in Berlin. Political thinker Paolo Virno may help here: “Ritual registers and confronts all sorts of crises: the uncertainty that paralyses action, the terror of the unknown, the intensification of aggressive drives at the heart of the community.” Nico Vascellari, who staged a loud, wall-of-sound performance at the last Venice Biennale, often uses folk masks, primal self-made costumes and raw wood for his energetic parades (Cuckoo, 2007), videos and installations, which involve a good deal of smashing (he piled and burned to ashes in a city square the contents of his show at MAN in Nuoro), and the disruptive energy of noise and punk music played by his band With Love. Dark and hardboiled, the characters populating Alessandro Pessoli’s paintings, drawings and ceramic sculptures move across nightmarish landscapes, while Simone Berti’s mutant creatures and machineries seem trapped in an inexorable, time-warped reality. Delightfully horrific are also the digital animations, drawings, paintings and sound installations by Roberto Cuoghi (now way past his notorious seven-year metamorphose, during which he assumed his father’s middle-aged physical appearance, gestures, and clothes). At Palazzo Grassi’s “Sequence_1,” he stole the show with complex layerings of pencil, ink, charcoal, paint and varnish in the series “The Axis of Evil” (2006-07, nine maps of the countries that George W. Bush accused of sponsoring terrorism), while his much-awaited solo show at Castello di Rivoli focuses on the iconography of Pazuzu, the Assyro-Babylonian demon of The Exorcist.

There’s an archaeology of desire and utopia. In May 1972, a Time magazine article about the ground-breaking exhibition at MoMA, “Italy: the New domestic Landscape,” stated: “The thrust of designers like Sottsass, Aulenti, Zanuso and the Archizoom group is not to decorate the psychic space around us but to extend and question it. This means a critical approach to social patterns, which starts with the language of shape.” Years on, the legacy of that radical language is proving fruitful — and definitely not only among collectives like A12 and Stalker, which formed in architecture faculties in the mid ’90s, before going public with projects, interventions and strategies following the steps of the early Radicali. One of the last projects by Sottsass, who died in December 2007, was the cabinets he designed for the remake of the Kinsey Reports on human sexual behavior by Francesco Vezzoli. Patrick Tuttofuoco’s colorful, pulsating structures, often venturing into public space and calling for attention, are the synthesis — or rather, the portrait — of group dynamics and the artist’s interaction with society and community. For “Revolving Landscape” at Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, he traveled around the world in 80 days, touching base in 17 fast-developing megalopolises, while for the upcoming Folkstone Triennial he embarked on another non-stop trip across the Balcans, along the tracks of the Orient Express. For Deborah Ligorio, mapping territories and architectures becomes a tool for visualizing a social landscape; of her video Il sonno (The Sleep) (2007), shot while flying over Naples’s volcano Vesuvius, she says: “It’s an impending threat, which could awaken at any given time. I want to talk about a typical attitude of social psychology: the drowsiness before the evidence, perhaps a survival technique.”

Riccardo Previdi’s mobile structures/sculptures for concerts (presented at ZKM in 2006), his shiny and frugal “Oversizing Aconà Biconbì” series in cardboard, plexi, PVC and neon stylishly reprocess the visionary possibilities of Techno-Utopia but also the capital lesson of Bruno Munari, an artist-designer who never stopped playing with perception and functional forms, for instance, with the Travelling Sculptures (1958) that would be folded and put in a suitcase, in order to take one’s cultural heritage around the world. Massimo Grimaldi conflates the seduction of objects and consumer goods with a forceful reflection on the social role of the artist, Andrea Sala deconstructs and reassembles the lexicon of Modernism, while Francesco Simeti plays with slickness and forced happiness of design to bring about disturbing images of war and conflict.

Christian Frosi applies the analytic vocabulary of Minimalism to his performative pieces, experimenting with combinatory logic, social dynamics and environmental concerns, from the sand dune he built at the Fondazione Sandretto last year, to the project of traveling to a remote Australian settlement to witness the apparition of the Yippipie cloud, which stretches up to 600 miles and moves at speeds of up to 35mph (Waiting Yippipie, which won him the 2007 Fellowship for Young Italian Artists at the Castello di Rivoli). At the intersection of geometry and organic growth, as attempts to give reality an order and a measure — superfluous, in flux and fragile as it may be — lay also the “humanized sculptures” of Luca Trevisani (showing in Milan at Gió Marconi and in Berlin both at Kunstlerhaus Bethanien and Mehdi Chouakri in May), who looks back on the rigor of Francesco Lo Savio as well as Robert Barry’s love for the ephemeral and invisible. On the other side, Piero Golia casts an ironic revenge on Minimalism and its macho epic of great gestures, turning guillotines, garden benches, brooms and showers into primary structures, but also choosing to question its elitism by running the independent Mountain School of Art in L.A. with artist friend Eric Wesley.

Not so surprisingly, in a country where still only half of the female population has access to work, the least devoted adherents to ‘fatherly’ traditions are a number of women artists, who mix defiance and derision to bring about daring and powerful statements. Monica Bonvicini hits the underbelly of Modernism, targeting architecture and Minimal Romantik as a gendered reservoir of tensions, desires and aggressions. The works by Lara Favaretto (who will participate in the next Sydney Biennial) and her passion for overturning hierarchies and implementing impossible projects, feel akin to the puns of writer Ennio Flaiano, who used to describe a dreamer as “someone with feet firmly planted on the clouds”; she can convince a group of villagers to try and make a donkey fly, suspend in mid-air a gipsy caravan (Poors are crazy, 2005), hail sardonic applause for the Queen (Frieze Projects, 2007), but also cut off her hair and make it into a rod with which to violently hit the wall (è così se mi interessa (2006). In her subtle videos, Stefania Galegati discloses the mise-en-scène of mass rituals, from the spectacle of Pope John Paul II’s funeral broadcasted worldwide, to an edition of 100 red T-shirts featuring, instead of Che Guevara’s icon, a bearded Giuseppe Garibaldi, the Italian 19th-century liberator whose statues grace city squares around the world. Micol Assaël (also going to Sydney) is hair raising. Her old-fashioned, menacing machineries bring on violent tactile assaults; the inner tension of her pieces reached a climax with the — literally — electrifying Chizhevsky Lessons (2007) at Kunsthalle Basel. In the same museum, Paola Pivi (enlisted for the Berlin Biennale, along with Giulia Piscitelli) had previously displayed a leopard feasting over cappuccini. Last January, at Portikus, she installed nine objects of polished steel, loudly pumping large jets of liquid from a five-meter height, which could be read as ingredients for a self-portrait. Defying physics and logic, she pursues the Borgesian task of reproducing in PVC, on a 1:1 scale, the Mediterranean island of Alicudi where she once lived. At the core of her grouping together of albino livestock for “My religion is kindness. Thank you, see you in the future,” (2007) at the Fondazione Nicola Trussardi in Milan, lays a pretty disturbing question: “Why do whites have most of the power?” Another good one, which she used as a title for an old sculpture is: “Do you know why Italy is shaped like a boot? Because so much shit couldn’t fit in a shoe.”