Let’s start with purple. It’s everywhere in the work of Martine Syms (b. 1988, US): the backdrop of the video Notes on Gesture (2015); the sixteen-foot-long, eight-foot-high monochrome painting on wood Belief Strategy VIII (2015); her sculptural works that appropriate lighting devices from film — powder-coated C-stands and plastic cucolorises; and her website — where the work, of course, is most likely to be seen — and where purple so richly envelops text and image that it seems almost to form something closer to context than background.

Though all of these share a single, uniform hue — something close to what Google Image Search wants me to call “eggplant” or “blue roses” — video stills and reproductions of the objects read in a spectrum of purples, from too pale to muddied. Nothing surprising in that. Beyond the vagaries of light, photography and CSS variables, we might recall Josef Albers’s introduction to Interaction of Color: “In visual perception a color is almost never seen as it really is — as it physically is. This fact makes color the most relative medium in art.” While such relativity provided the very driving force behind Albers’s work, it has haunted philosophical inquiries into the nature of color; Wittgenstein, for example, failing to rework Goethe’s famous physiological theory of color into a set of logical propositions, lamented that, in the end, “there is merely an inability to bring the concepts into some kind of order. We stand there like the ox in front of the newly painted stall door.”

Where philosophy falters, however, information capitalism advances, untroubled by what, preferring to ask how much, whether defined in CMYK, RGB or whatever. And it’s not merely a philosophical inadequacy. The very language of color pales to the point of insignificance when compared to the easy specificities of hexadecimal web color values. Eggplant? No. It’s #482e84.

A parallel can be drawn between the simultaneous uncertainties and specificities of color in general and the subcategory of colors that so frequently serve as a metonym for race. The latter, similarly, can’t be rationalized, can’t be brought into order. Race is an illusion, an abstraction, a generality. And yet it is a forceful, historically conditioned social relation, and as such it is experienced in very real and highly specific ways. Syms’s inquiries into representations of blackness, and black people, and often specifically black women, move along the spectrum between mediated generalities and something much more precise.

Color has another function here. Like its clear antecedent, International Klein Blue, Syms’s purple works as a marketing device, a key component in a strategy for branding and promoting the figure of the artist — not so much Martine Syms as “Martine Syms.” She invites this idea, dubbing herself a “conceptual entrepreneur,” which I read less as being in the business of selling concepts than as selling the concept of being in business. Anyway, as a rule, artists are selling something — or trying to — while self-figuring and self-marketing, for many, form a fundamental feature of neoliberal daily life.

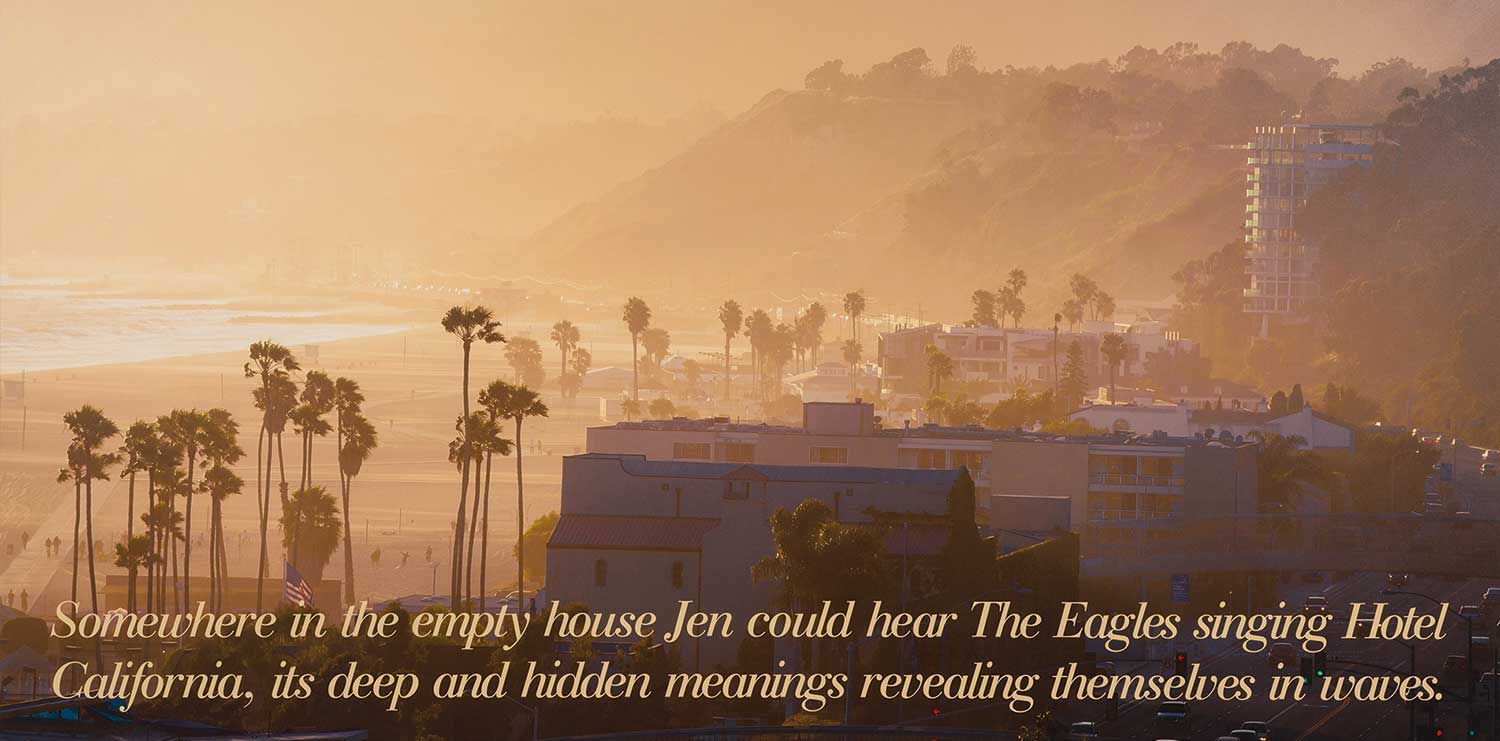

Syms interpolates this self-figuring into a broader investigation of representations of race and gender. A Pilot for a Show About Nowhere (2015) is both a documentary video essay on the history of the black sitcom and a fictional account of a sitcom called She Mad. The show’s protagonist, “a young, ambitious black woman” named Martine, works in “the Los Angeles creative industry,” while she and her friends “try to create the lives they want, and deal with the unrealistic goals they and society have set.” That television has served to inculcate these unrealistic goals is both the point and beside the point. The timeworn critiques of popular culture often presume that we don’t understand what we consume; yet, as Syms reminds us in voiceover early in the video, “television viewing has always been highly personalized and highly politicized.” If savvy viewing, or understanding the ideological operations of a TV show, does not amount to liberation — from unrealistic goals or from anything else — it does at least offer the tools for attempting to control your own representations. Fictionalizing herself into the sitcom format with a certain deadpan irony, Syms assumes a position neither exactly critical, nor, of course, acquiescent, instead offering an illustration of the formative powers of popular culture, but also of its malleability in the hands of its consumers.

This, of course, is conditioned by the digital technologies of the present. It’s there, in its most simplistic form, in every meme that uses a clip or a still from a Hollywood movie (She Mad takes its name from a meme). Syms’s installations of cinematic lighting equipment seem to say: You are already an image. But they point as well to sources that, consciously or not, determine what kind of image you want to be, what kind of story about yourself you want to tell. “Think of your most Internet-famous friend,” she says in Pilot. “Do you even recognize her life? Does it have a plot? Is there a will-they-won’t-they romance at its core? Does she find herself in wacky situations? If you can’t think of such a friend, you are that friend.” Or take, once more, her use of the color purple: As Syms makes clear, it has yet another meaning, and that is, of course, The Color Purple, Alice Walker’s hugely popular, critically acclaimed 1982 novel about the lives of African American women in the south during the 1930s, adapted for the screen and again as a Broadway musical. The color then doubles as a tool for self-fashioning and a reference to a beloved narrative of black femininity–cum–popular culture phenomenon. Purple is always also “Purple.”

TV and Instagram, however, are but two elements in the morass of mediation and memory — the accumulated mass of depictions and caricatures of black women, the historical cultural strata of a country built on white supremacy, the assumptions and ideologies of the past and the present refracted through infinite stories, pictures, information, all coexisting with an unmanageable flood of user-generated content. Syms seems to delight in the vastness of it all. Out of inundation she pulls fragments and presents each — even when only vaguely legible — as something solid, a specimen to be considered, an island in the stream. That is to say, even as she works on a thematics of representation, she is often less interested in those questions of the construction or deconstruction of image, stereotype or identity, as she is with a kind of sifting through.

For example, her video project Lessons (2014–16) consists of 180 thirty-second segments of found and original footage, each, according to Syms, featuring a black figure (though sometimes unseen). Running from silent-era film clips to mundane home movies, the piece comes in and out of focus — literally, but also in terms of what the individual lessons here might be. It’s clear enough when we watch politically charged rapper Sister Souljah on the Phil Donahue Show in 1992, speaking about the exclusion of African Americans from the promises of capitalism and the state; or the segment of a woman sitting on a stool against a white backdrop, her face cropped largely out of frame, reading from James Baldwin’s The Price of the Ticket; or even, perhaps, when we hear the theme song to the 1990s sitcom Moesha, playing over abstract video: “Up in the morning / A new day is starting / It’s me, it’s me / Am I realizing my responsibility? / It’s me.” But other segments, if evocative, come across more didactically ambiguous: camcorder footage from the fight that broke out between white and black teenagers at a bowling alley in Hampton, Virginia, in 1993, an incident famous for the resulting prosecution of future NBA star Allen Iverson; a blurry and jump-cutting scene of a gospel choir; or handheld footage, which looks to be from the ’80s, of black families seated at a banquet, as a band plays on stage.

Their ambiguity mirrors the fleetingness in the form of the work. Many of the fragments that make up Lessons have a fascinating and intense specificity, almost to the point of feeling arbitrary. You could imagine her just as well pulling a different set of 180 thirty-second clips. In The Grey Album, Kevin Young’s 2012 wide-ranging book of African American cultural criticism, which Syms has cited as inspiration for Lessons, the author remarks that “the dominant mode of this post-soul era is fragment: pieces that don’t so much stand in for others (as in postmodern metonymy), or as mere metaphor (as in modern blues or Waste Lands), but that serve as a series of synonyms, equivalences as a form of equality.” Lessons is a work of synonymity, playing precisely on the endless availability of such material. Identifiable or not, well known or obscure, the sources become commensurate through the structure of the editing.

Notes on Gesture (2015) also works on the logic of the fragment. The video consists of a series of short clips, each no more than a few seconds, featuring the artist Diamond Stingily performing a series of actions, hand gestures and facial expressions. Each clip loops several times before cutting to the next, and fragmentariness is emphasized in the abrupt interruptions of Stingily’s movements, echoing the jerky repetitions of a meme or a Vine. Notes presents a kind of satirical taxonomy of black female gesture — one that is happily unsystematic and necessarily partial. Yet even if we recognize a given gesture as familiar or caricatured, the rapid repetitions render it increasingly abstract and inscrutable.

Syms realizes a more pronounced effect of inscrutability in her photo series More Than Some, Less Than Others (2014–16), a title that suggests vagueness and amplitude as a theme. A few of the images are more or less identifiable: a page from Aunt Sally’s Policy Players Dream Book; a grainy close-up of a woman’s face taken from a clip that appears in Lessons; and a screen with white text on Syms purple that seems to float in a darkened space (probably documenting a lecture), which reads, “When entertainment frames the future, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.” Most, however, provide few clues, their context, meaning, or stories withheld: an orange curtain, a silhouette of a hand, a garment with the words “life is a paradox” in gold letters, hanging from a white wall. It is unclear in most cases whether they’re “originals” or sourced from somewhere. Apart from their fragmentariness, these works, whatever their sources, share with Lessons — as well as Pilot, parts of which are shot on smartphones and webcams, indifferently framed — a penchant for what Hito Steyerl calls the poor image: “It is a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution.”

Syms’s poor images reflect an interest in the everyday — not the real, as such, but rather something closer to a prosaics of representation. Her text “The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto” issues an exhortation away from the seductions of that corpus of temporally and spatially expansive black imagination (Samuel Delaney, P-Funk, Sun Ra, etc.) and the uses to which it can be put, eschewing “unexamined and hackneyed tropes” for more realistic ones. Even the mundane is a trope. And even old camcorder footage, new webcam footage and unplaceable pictures are incidents in the ongoing history of representation. They are both right here and out there, in the abstractions of the image world. In Lessons, Syms draws her fragments from the vast store of images of black figures. She reifies them, animates them, presents momentary specificity, and each fragment, in turn, slips back into generality. Remember that hers is a show about nowhere.