João Ribas: I’d like to begin by discussing this post-humanist condition underscoring so much of your practice — ranging as it does from sculpture to drawing, video, ceramics, and painting.

Sterling Ruby: Post-anxiety, post-cynicism, post-transgression, post-depression, post-war, post-law, post-gender, etc., etc., etc. For me it seems fitting to the purpose that all of this baggage is the reason we have to be post-humanist. There is just too much information for anything to be coherent or whole. To be quite honest I had never thought about post-humanism in relation to my work until Robert Hobbs started the discussion while preparing his essay for the JRP|Ringier book. What makes it hard is that there is no real definition of post-humanism, which seems fitting for the times and for the topic. During the ’80s and ’90s, Félix Guattari and Jean-François Lyotard were focusing on technological advancements and sociological peripheries that seemed to suggest a future transformation or liberation of some kind. At present Mike Davis sees the post-human as an entity of excess, an individual or group who can’t take any more. Even Steve Nichols who published The Post-Human Manifesto in 1988 suggested the situation might be generational.

JR: Yet somehow your work seems particularly grounded by a specific notion of ‘transversality’…

SR: Well, one outcome of this ‘post-situation’ is generating a feeling of continuum, as an adjustment or a way of coping. It certainly doesn’t feel as if it is anything other than a strategy for survival. I recently started thinking that I apply a kind of ‘transversality’ not only in theory, but also as a work ethic. My intention is to use many media as a kind of schizophrenic labor strategy. It seems very easy now to say it, but it has taken me years to convey that this scattered routine belongs within a coherent trajectory. Works may not look the same formally, they might not even be within the same medium, but there is a lineage that links everything that I do together.

JR: There are two poles that emerge directly from your early sculptural and drawing work that seem foundational. On the one hand there is the masculine orthodox language of minimalism, which your work has had an agonistic relationship with, in its reappraisal, from the start. On the other hand, the notion of representing, in symbolic form, marginal states and forms of containment like the penal system and incarceration, normative sexuality, the notion of a stable social identification, as well as attempts to move out of these things that are often deemed types of ‘pathologies’ — gangs and criminality, transexuality, abjection… These are in some way the repressed ‘other’ of minimalism…

SR: These two poles (formalism and representation) have always seemed to be in opposition of one another, but for me they became mirrored necessities, especially over the past decade working as a contemporary visual artist. I went to a foundation college in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, for four full years; I learned the visual basics like perspective, color, composition and form. In that curriculum I did nothing other than still life, figure studies, mixing colors and additive and subtracted sculpture. After that my education switched completely; I wound up taking almost no studio classes, enrolling mainly in psychology and theory courses. Having one versus the other seemed absurd and I often thought about what it would be like if I had done neither. This is where my graduate education fell into a downward spiral, which ultimately led to not receiving a degree. I felt like I was regressing, that I had too much education, and that this was preventing me from making anything other than premeditated work.

The antagonistic approach that I have taken towards minimalism started during this period. I thought that Judd’s writing was too much of a handbook and that the movement was restricted because of it. The ideas of territory and how things were deemed minimal were in dialogue with masculine authority or, more significantly, who controlled the movement, and I found that to be problematic. I have always thought of art as similar to poetry, that it can’t be proven and yet, if done right, has a sense of unmistakable aura. This idea is also in direct conflict with education and training; it brings with it my generation’s shift towards primitivism or naivety. My disobedience of the regulations that set definition to the movement manifested itself in certain pathologies. Everything started to collapse in on itself, and there became no line between formalism and representation. The minimal form was in fact no longer the item of exterior object-hood, but instead the vessel that contained all aspects of marginal states.

JR: Is there also a sense of embracing devalued cultural forms, say like ceramics, or graffiti — as demarcations of territory and collective identity?

SR: Yes, absolutely. Ceramics in particular correspond to the therapy-driven collective identity. The medium of clay for me is universal. It holds all sorts of shared principles with reference to desire, immediacy, sexuality and repression. The malleability of the clay becomes truncated via the kiln, which is also a kind of a monumental allegory for where we are as a generation. Perhaps it characterizes our incapability to truly feel as if there is an innate expression… that even this is an incarceration of current times. It is converted through the firing into a monument of the gesture that it once had. Graffiti is similar to this as well. It seems like a kind of collective mark making, as much as it is about territorial pissing.

JR: One of the terms that seems to keep coming up in discussions of contemporary art practice is the idea of ‘sincerity’ — almost taken on as a positive, critical term. At the same time, your work has often been reproached for being precisely the inverse. I find it somewhat puzzling that sincerity would be taken up by a generation of artists as a critical term.

SR: Yes, I agree with that completely. Sincerity seems to have become a designation for our generation. It feels like the backlash to cynicism or even postmodernism. I guess I hadn’t thought that it was a critical term as much as a way out of conceptual pessimism, maybe even anti-critical. I get pretty down on the fact that people equate sincerity with being positive. I do think that my work is sincere, but this often gets overlooked because of its underlying hostility.

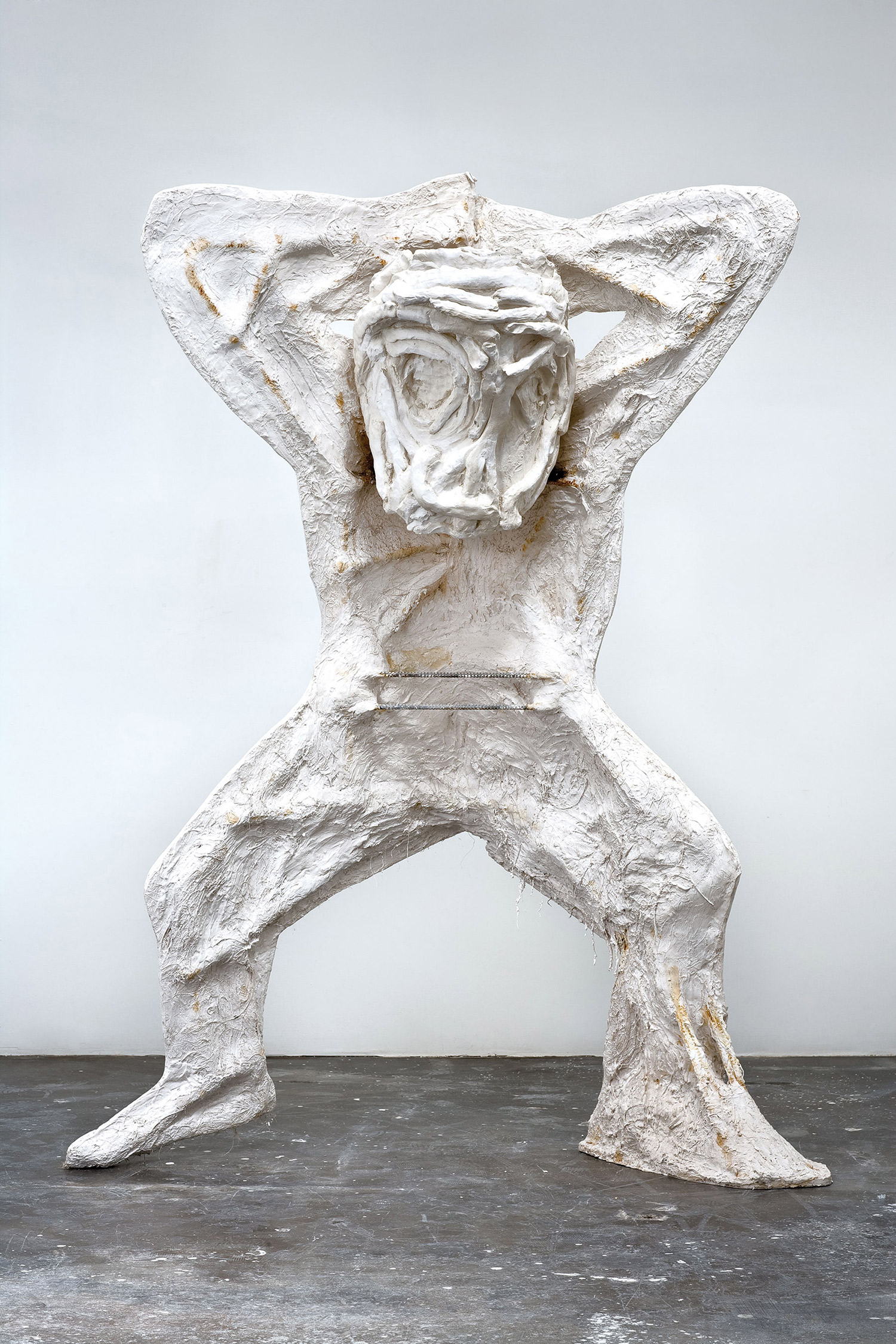

JR: I’m curious about The Masturbators (2009) in terms of its structured patheticalness — the corporality is so intense and aggressive as to almost be a form of torture…

SR: I started The Masturbators almost a year ago. I originally had a different idea for the work. I hired one male porn actor and asked him to masturbate to climax in a room by himself. The camera and crew were in the adjacent room with the lens being focused through a hole in the wall. I expected the actor to run through the request with ease, but the reality of it was that he couldn’t do it. His embarrassment over his profession and not being able to masturbate to climax became the project itself. I followed the project over six months by hiring an additional eight actors, shooting them all the exact same way. In the end only three of the nine actors were able to climax; the ones who could not had reactions ranging from subtle humiliation to violent disappointment. There were times during the production where it got very tense.

I had focused so much on the super maximum penitentiary stuff the years leading up to this, that I had contemporary masculinity in the back of my head. I read a great line from Lorna Rhodes’ Total Confinement, which stated: “The secret of violent men is that they feel ashamed — deeply ashamed over matters that are so trivial that their very triviality makes it even more shameful to feel ashamed about them.” I thought about this quote every time I finished a shoot with one of these guys. I mean: who should be expected to climax on cue? The project became like a core behavioral study once completed. It seemed brutal, but honest.