Danae Mossman: Can you describe the ideas driving your practice currently, and what form they may take?

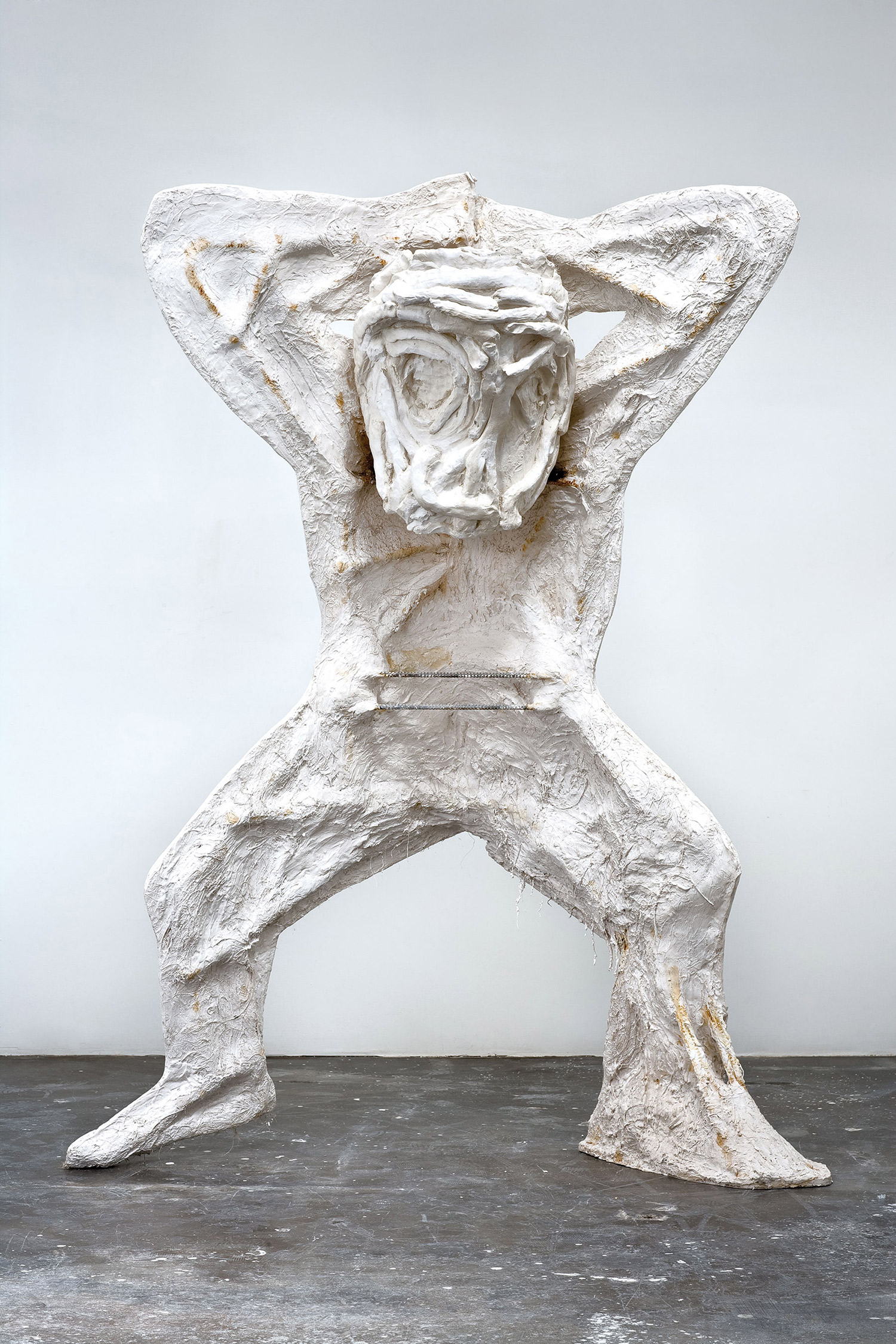

Sriwhana Spong: I’ve recently taken up ballet classes again after 15 years, at the encouragement of a dancer, Benny Ord, who I have been working with on a new video piece. This work Costume for a Mourner involves the construction of an imagined dance from the ballet “Le Chant du Rossignol,” originally choreographed by George Balanchine for the Ballet Russe. I was fascinated by the original costume designed by Matisse, which looks like a huge white liturgical robe made from thick felt. I was curious as to how the body might move within this costume. There is no known footage of the original ballet as Diaghilev felt the technology at the time did not do justice to his artist’s dancing.

I remade the costume based on images of the original, and passed it on to Benny who created a three-minute dance. This piece is very much about distance, translation, archives and the imagined gaps between documents. My ballet teacher Timothy Gordon is full of these wise sayings about the body and movement like “wherever the skeleton goes the muscles must follow.” This has increased my interest in the process of a work: this idea that it’s not where the skeleton heads, but how it gets there. As I attempt to capture certain lines and balances, I realize that what interests me is not the forcing of the body or the material into a set mold or ideal. So in a weird way, what is necessary for me when dancing, has become interesting to me in areas of my practice — allowing moments of chance, of failure, of collapse.

DM: This movement between points, imagined spaces between fact and fiction, the melding quotidian and liminal forms, has manifested in your practice in various media — yet often film is your first port of call. Can you talk about how the extension and compression of movement and its limitations or failures were explored in your film Halberd Head (2008)?

SP: I filmed Halberd Head at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I had spent a lot of time looking at the East Asian artifacts, and was amused that only still photography and no moving documentation was allowed in the Museum. I wanted to give these objects from my own estranged heritage a new life, so I documented them by surreptitiously winding on a canister of Super 8 film by hand. I knew that I would fail to properly capture these objects — and the final piece is just abstract bursts of light that have picked up the rhythm of my hands winding on the film, like a dance in a way. I’ve always liked the notion that artifacts carry the vibrations of their makers’ hands, so I like to think that in Halberd Head, my film and the objects on display, are the same — receptacles for movement.