Jenny Schlenzka: How did you become invested with movement?

Simone Forti: Before I got seriously involved with dance I painted. I was married to Robert Morris. We dropped out of college and moved to San Francisco in 1956. He taught me how to stretch canvases, and I made big Abstract Expressionist paintings, which weren’t very good. But there was a dance school nearby, where I was going once a week for fun. That is where I met Anna Halprin who had just decided to completely concentrate on improvisation.

JS: Now that improvisation has become part of the regular dance repertoire, it is difficult to imagine what was so special about it back then in the late ’50s.

SF: Anna’s workshop reminded me of work I had encountered in art schools, where we would spend hours exploring different qualities of line, or the opposition between dark and light. Anna would have us work with weight or the negative space between two bodies. She asked us to put all our attention into it. Later, the work in Robert Dunn’s classes was more about a simple idea that you would take to the extreme.

JS: What was the most important thing you took from that time?

SF: During the time with Anna was kinesthetic awareness: to be aware of the sensations in your body and your movement impulses. Anna was also working anatomically. We would study a particular part of a skeleton and spend half an hour exploring the sensations of movement in that area. She would teach us that any movement has its quality. It might be very tight, very precise, or very soft. We were also learning to be aware of the arch of an improvisation. A sense of orchestrating with other dancers, which I think in America comes from jazz. This idea that you can be a group of artists who are paying attention to what everyone else is doing. And then, there is that moment when an individual takes a solo and the others step back as a support. Then, you sense when the solo is over, and you let that person join the support again.

JS: Which reminds me of your dance construction, Huddle, from 1961. It consists of six or seven people who gather in a tightly packed group, then take turns climbing over the mass, forming a living, moving sculpture.

SF: Yes that’s true, this piece only works if the performers pay very well attention to what everyone else is doing. But the Gutai Group was also a big influence.

JS: The Japanese avant-garde group from the ’50s?

SF: Yes. I found a magazine with pictures of the Gutai Group at Anna’s. I was starting to need something more minimal; because of the intensive workshops we would work in the summer, from 10 in the morning until 2 am at night. I was just drunk with movement. So, the idea of something that was one movement was just what I needed. In the magazine, I saw Murakami Saburo’s Breaking through Many Screens of Paper (1956). Another piece I remembered was Kazuo Shiraga’s Please Come In (1955): a man with an axe, looking like he was about to swing around and knock down the logs that leaned over him like a tipi. I liked wild things.

JS: Is that why you moved to New York?

SF: At first New York was a shock. I missed the trees and mountains. The city looked like a house of mirrors to me. I remember thinking, “I still have nature because I still can feel gravity. I have mass and I have weight. And that is nature.” I think we moved to New York mostly because Robert really needed to see the Abstract Expressionist painters like De Kooning. He spent the whole year reading and looking at art, and did not make anything for a year. And that turned out to be very productive. By the end of that year he was not interested in Abstract Expressionism anymore.

JS: What happened to your artistic development?

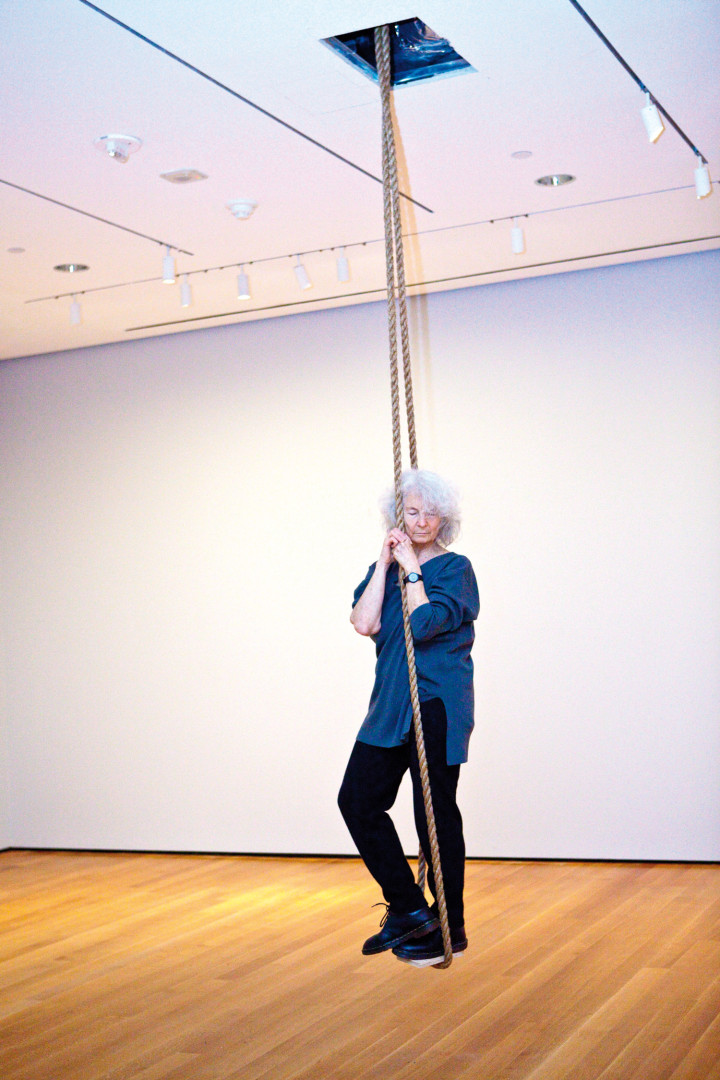

SF: I met Robert Dunn. He was teaching a composition class for dancers, at the Merce Cunningham Studio. He started by talking about John Cage. The idea of deciding what you are going to do through chance operations was very interesting to me. One thing that impressed me was the fact that Cage did not like improvisation because he thought one was always going to one’s own taste. In Western music there are certain expected patterns that confuse the ability to really just hear sound. By deciding things by chance, you got away from your taste and patterns and you could just purely hear the sound that came up. One summer everyone was going to climb rocks and I got sick and I could not go. It hit me hard, because I had very much looked forward to it. That gave me the idea to find something to climb. Cage needed to hear sound so he created a situation to hear sound. If I needed to climb, I could create a situation where I could climb. I needed to sense my weight and I came up with the idea for Huddle.

JS: In Huddle many of your influences merge; Anna Halprin’s interest in the quality of movement, Gutai Group’s concentration on one big gesture, the idea of chance operation from Cage.

SF: And the fourth element was the photography of Muybridge, especially the images of men working.

They are not at all stylized but all about the body organizing itself to fulfill a necessity. I often felt that dancing makes it hard to really see the body because it is moving around in so many ways and directions.

JS: Many of your pieces focus on the body and its sculptural existence.

SF: The dance constructions were arranged in space in a way that viewers could walk around them. And in fact, at the first concert at Yoko Ono’s loft in 1961, at one point two dance constructions were happening simultaneously. It was like a sculpture garden. You do not have to look at them from beginning to end.

JS: In this context, it is interesting that the wooden boxes in your whistling duet, Platforms, look very much like Robert Morris’s early sculptures.

SF: I don’t know, I just came up with the form. After I drew them I was thinking, “How am I going to build this?” And Robert said “Don’t worry, I’ll build it for you.”

JS: Your pieces are immaterial and ephemeral. Yet, they are based on scores and can be repeated. Do you ever think about preserving them?

SF: No, but maybe I should. No one could own the Huddle though, or have exclusive rights to perform or teach it. It is part of its nature that everybody owns it, and that it spreads out. But still, it would be nice if it had some protection and definition.

JS: Let’s talk about Handbook in Motion (1974), a very special book. Could you talk about the subtitle: An account of a ongoing personal discourse and its manifestation in dance?

SF: It is autobiographical. The title suggests the working together of the rational and the body’s intelligence. What we know about things through our bodies.

JS: The book marks a departure. In the beginning of the ’70s you started doing different work. I am thinking of the animal movements.

SF: Partly, I was just looking at movement. But I was also looking for the roots of dance behavior. We tend to consider dancing as evolved stylized behavior. But expression through movement, playing with movement, or even movement rituals, seem to come from a very early part of evolutionary development that we share with other species. The first dance I made from my observations in the zoo was based on a flamingo’s pulling up his foot, trying to go to sleep. I adapted it to leaning back as if lying down, while trying to stand on one foot. And also on a polar bear, swinging his head.

JS: You also worked with Dan Graham in Nova Scotia. He cites you as a big influence.

SF: I remember a work of his I participated in entitled Helix/Spiral (1973). Two people, filming each other turning around their axis. But I am not sure what exactly my influence was. Dan was working very much with visual perception whereas I was working with kinesthetic perception.

JS: Why do you call yourself a movement artist, as opposed to a dancer or a performer?

SF: Most modern dance has never interested me. Even Cunningham hasn’t.

JS: What is it that interests you?

SF: Movement.

JS: But isn’t dance movement? What interests you in a grizzly bear running back and forth in the zoo, and what bores you in a modern dancer doing the same?

SF: Because a modern dancer does not run back and forth. He would only do as if he was running back and forth.