Lina Bertucci: As a visual artist, is your approach to filmmaking different from a traditional filmmaker’s?

Shirin Neshat: From the beginning I knew that my film would not be a traditional film. I was neither capable nor interested in making a traditional film. But at the same time I had every intention to make a film that could ultimately be appreciated by the general public. Then the question became “what type of film could I envision that is at once faithful to my own artistic signature, yet dare to step forward to embrace a new language that I have no previous experience with?” I understood that unless the main rules and logic of filmmaking were applied to the film — such as a dramatic narrative and a clear character development — the picture would basically function as an extended video installation. Women Without Men has been all about possible ways to find a balance between art and cinema; the same conceptual approach of my previous work with a clear narrative.

LB: What was the concept you were aiming for?

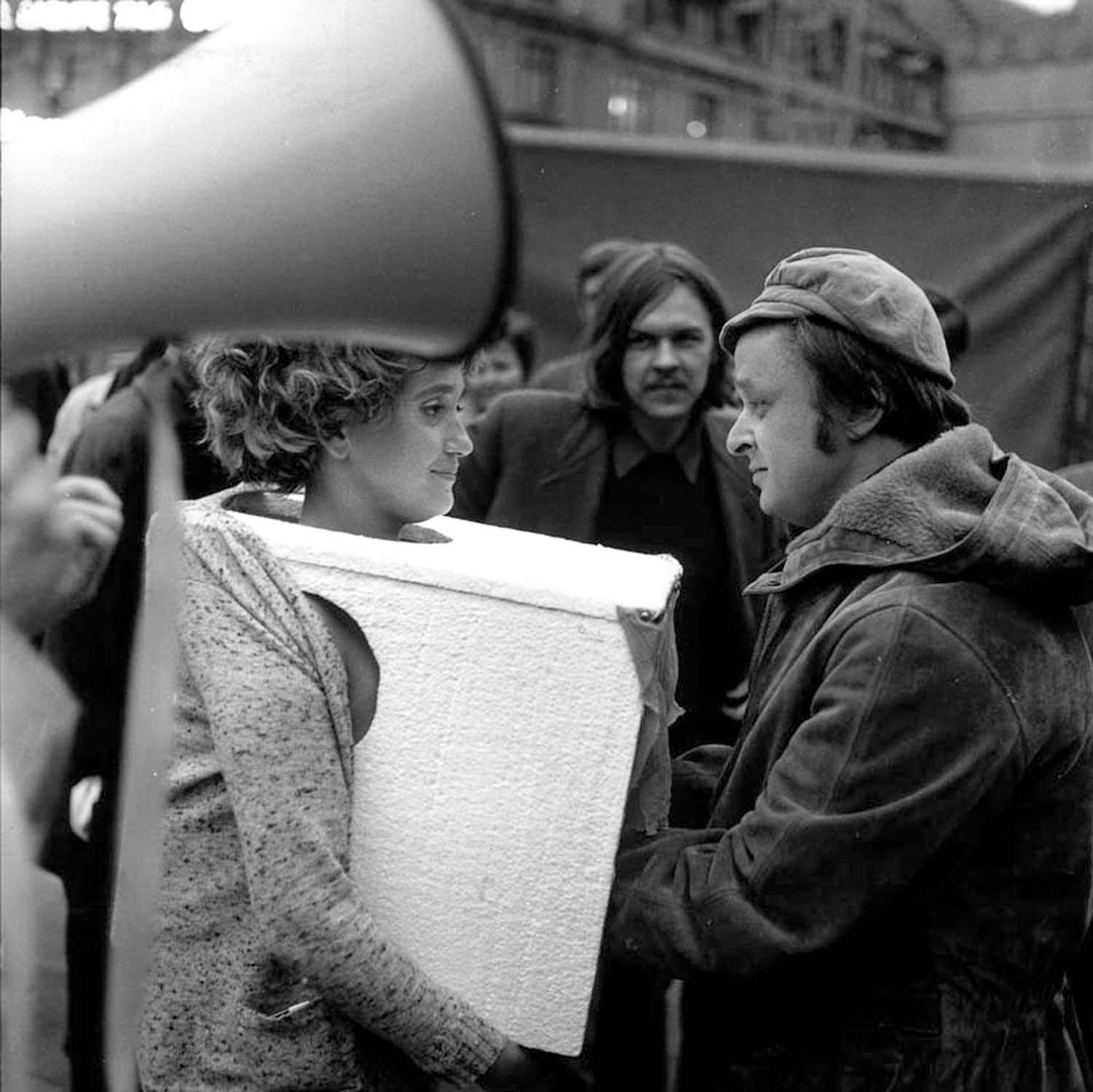

SN: I have always felt that as visual artists we tend to express our ideas through formulation of concepts, where filmmakers develop stories. I wanted to see if I could now tell a story. So first I approached the film as I would have approached any of my video installations, or photo series. I tried to find the overall concepts that interested me to convey to my viewers, then I developed the narrative. The central theme being the poetic connection between the female characters and the country of Iran; they all seemed to fight for the same things: the ideas of ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy.’ The film constantly navigates through the four women’s lives and plights, as each of them run away from their personal crisis to find peace and security in the natural surrounding of an orchard, a timeless and universal space. The scenes of street protests represent a very specific and important socio-political moment in Iranian history.

LB: Women Without Men is a novel you adapted for cinema. What drew you to this novel?

SN: When I was searching for the right story to re-adapt into my first feature, I knew that I would need to find a novel that somehow fit my visual and conceptual approach. I had known about the novel Women Without Men by Shahrnush Parsipur since I was young, and it was brought again to my attention in 2002. This novel, written in the style of magic realism, not only lent itself to strong visual imagery, but it also beautifully moved between the orchard and the city of Tehran, heaven and earth, emotional and political states of the women and the country. Also, I must admit that I was very interested in the period the story takes place, which is in 1953. I thought this was a rare opportunity for both Iranians and Westerners to look back at Iran when it was a very modern and a secular society. Most Iranian films focus on Iran after the Islamic revolution, when the country was transformed into a strictly religious society. In addition to the cultural and political dimensions of the novel, I found myself fascinated by the author herself, and the life she had endured as she spent years in prison, suffered from mental illness and lived in exile. I strongly felt that a re-adaptation of Women Without Men would pay tribute to this important female artist who would otherwise be forgotten.

LB: We met for our first interview in 1997 after your second video piece Shadow under the Web (1997). I was thinking that the language of that early piece has clear echoes in this feature — how a woman in specific spaces like alleys or the garden serves as a metaphor.

SN: This is indeed true, a lot of time has passed and my work has changed a great deal, but certain things seem to remain constant. Images of women in alleyways and gardens, and of course the way female characters always seem to flee from their difficult lives. I suppose the one thing that has changed most in my work is the introduction of the narrative element.

LB: Shoja Azari is credited as co-writer of the script. How did your collaboration evolve?

SN: Shoja and I met during the making of Turbulent, and we have continued our collaboration ever since. Shoja himself is a visual artist and a filmmaker, and has quite an active career. In Women Without Men Shoja indeed co-wrote the script, but his involvement was far beyond the script; his role became that of co-director in the way that he was engaged with every aspect of the making of this film. To say the least, Shoja helped me to maintain my own artistic signature.

LB: Your work deals with potent political issues and gender politics; yet it stems from a very personal history. How do you manage your political position and artistic practice?

SN: Politics have been an integral aspect of my work whether working with photography, video installation or cinema. Generally I feel that it is practically impossible for Iranian artists to distance themselves from politics as our lives are so affected by political developments inside and outside our country. Naturally, there is a great degree of grief and frustration when a life is lived in exile, separate from your loved ones and your place of birth, all of which imposed unfairly by governments and people of power. Therefore, my work seems to be expressing the sense of anxiety and sadness that I feel in relation to my personal experiences as well as the profound social anxiety that I feel for the entire world. So, in many ways, my intimate monologue seems to always find its way toward a larger dialogue.

LB: How did you find working with actors?

SN: I had rarely worked with professional actors in the past and in this film I was working with four main characters as well as a number of other actors who had secondary roles. I think at the end the success of the performances was due to the intimacy of our relationships, the fact that many of the actresses in a way identified with the roles and played themselves.

LB: Could you tell us more about the decision to set the film in Iran during the CIA coup and the reinstatement of the Shah in 1953?

SN: Both Shoja and I felt that the historical context of this film was very important, as the world only seems to remember Iranian history after the Islamic revolution. More so for Iran’s younger generation, those born after the Islamic revolution, who have little information about what Iran was like before the current regime. On another note, I have always felt a lot of frustration in how, since September 11th, within all the debates about the conflicts between the US and the Iranian government, so rarely American media refers to the Coup in 1953, which was organized by the CIA, which was directly responsible for overthrowing a democratic government. In many ways, most Iranians believe that our country would not be where it is today had it not been for this American conspiracy, which became a pivotal moment for Islamic Revolution and the beginning of the profound conflict between the US and the Middle East.

LB: Aside from its political dimension, the film is very beautiful and feels very authentic in respect to that historical period in Iran. Tell me about the process and approach to art direction.

SN: We paid a lot of attention to the look of Iran in the ’50s; we researched Iranian architecture, interior design, fashion and style of the time. We traveled several times to Morocco to look for locations, to see how we could recreate Iran of the ’50s in Casablanca. Then, together with our production designers — particularly with Iranian artist Shahram Karimi — and our modest budget, we created numerous authentic and traditional spaces such as the bath house, the brothel and each female characters’ house.

LB: You often talk about this film’s long conception process of six years. What was the genesis of the project?

SN: The production of this film became very lengthy on both practical and artistic levels. First of all, it was quite a challenge to raise funding, which ultimately came from the German, French and Austrian governments for an Iranian/American director shooting in Morocco! Artistically the novel proved to be extremely difficult to translate into a film script, particularly for its magic realism style and the fact that it had four primary characters who needed to be developed. We began writing the script in winter 2003, went into production in spring 2007 and finished editing in summer 2009.

LB: How does the script differ from the book?

SN: It’s fair to say that the film is only 30 percent faithful to the novel. Originally the writer wrote separate short stories about each one of the characters, and at some point decided to join the stories together. For our film the women’s stories were told in a parallel manner. Also we strongly felt that in order to translate this novel into a film script, the magical aspect of the story had to be reduced. I also did not entirely agree with the author’s portrayal of the female characters, as they became too much of a victim.

LB: You won the Venice Film Festival’s Silver Lion last summer. Did you expect to win? What was that experience like?

SN: When we arrived in Venice, I was already overwhelmed by the fact that my first feature film was in the competition category of a very distinguished film festival, and had no other expectation. Therefore, the announcement of the prize, which came after we left — and happily made us return for the reception — came as a total surprise. I must say during the ceremony, since everything was announced in Italian, I had no understanding of what prize I was receiving, until later when I found it was for the best director and indeed I was beside myself. I think the most important message of the prize was that the festival and the jury welcomed and encouraged new experiments in cinema and after six years of hard work, this acknowledgement felt unbelievably great!