Cultural transgression and a semiotic sensibility characterize the work, personae and positioning of Öyvind Fahlström, an artist who continues to attract attention in the contemporary art world. An early example of today’s nomadic artist, he was the son of a Swedish mother and a Norwegian father. His parents met at the Scandinavian Society in São Paulo, the city in which he was born in 1928. In July 1939 he was sent to Sweden to visit his maternal relatives, a summer stay that turned out to be an eight-year-long forced separation from his parents, due to the war that broke out in September. During his time in high school in Stockholm he showed a strong interest in foreign languages. In addition to Swedish, his mother tongue, he learned German, French and Latin and studied Sanskrit and Greek independently. These early experiences of semiotic difference and border transgression laid the foundation for his future work as an artist and author. He lived in Stockholm until 1961 when he moved to Manhattan, where he lived, with some breaks in Europe, until his final year when he returned to Stockholm and died of cancer in 1976.1

Fahlström made new worlds out of complex visual and verbal systems of signification. At his untimely death he left a dense and disparate body of work, containing poetry, poetics (including the first concrete poetry manifesto), criticism, journalism, sound art, film, performance and, perhaps most importantly, two- and three-dimensional works including installations and his “variable paintings.” Some of his productions were new systems of visual forms or phonemes; others built upon already existing material, using recycled popular culture or political and geographical mappings.

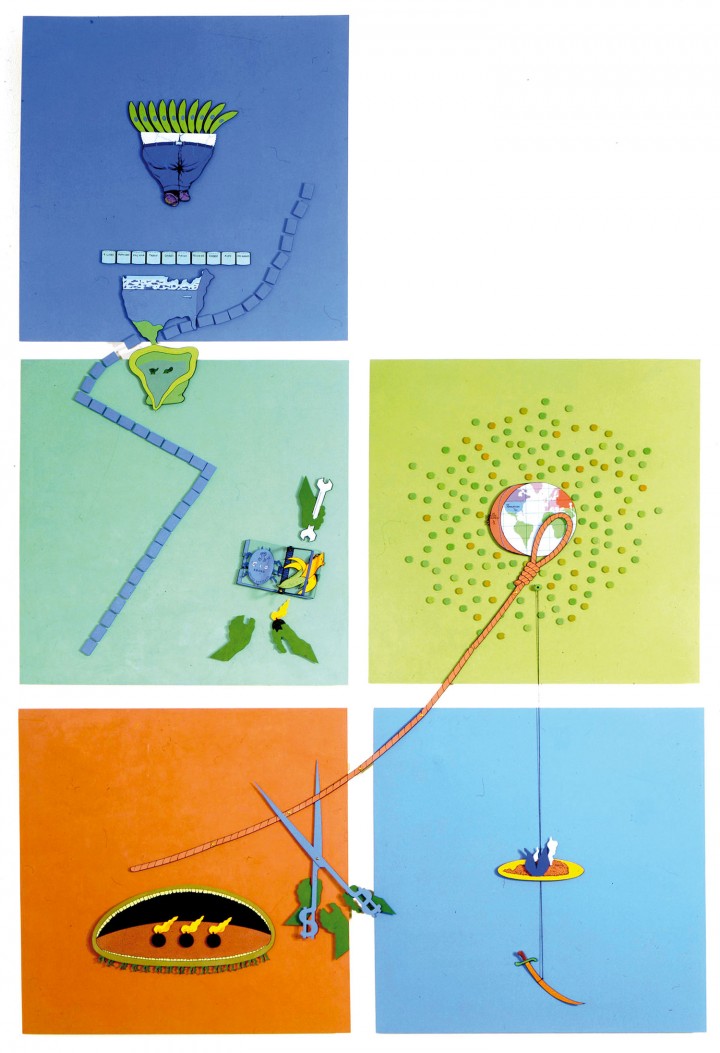

A few works can be considered milestones. In 1953 he wrote Hätila ragulpr på fåtskliaben — an opaque title that translates from Swedish as Hipy Papy Bthuthdth Thuthda Bthuthdy — in which he advocated the use of language as concrete matter, rather than as an expression of content, feelings or narrative. The publication was later given the subtitle “Manifesto for Concrete Poetry,” and is considered an early and isolated example as such. During these years he also wrote and published several volumes of poetry. However, these were distributed by small, independent publishing houses and were rarely commented upon by critics.2 In the mid ’50s, Öyvind Fahlström turned to painting while continuing to formulate his textual aesthetic. He founded the concept of “Signifiguration,” which proposed relationships between visual and verbal signs. His first oil painting, Ade-Ledic-Nander I, Rythmic Momomanometer (1955), now part of the collection of Robert Rauschenberg, was followed by the larger work Ade-Ledic-Nander (1955-57), currently in the collection of the Moderna Museet, Stockholm. As important realizations of his ideas, these first two finished paintings were part of a planned series of twenty works meant to designate three societies, or “clans,” known as Ade, Ledic and Nander, which were hostile to each other and in a constant struggle for power. The names of these units were taken from science fiction literature. These larger paintings are some of Fahlström’s most intriguing works. They visibly represent both a macro universe and a myriad of small forms or signs that interact in a seemingly regulated manner.

In order to explain the work to its first owner, collector Theodor Ahrenberg, Fahlström wrote a manuscript that is a universe in itself. Written in a language suggestive of bio-global space, the text presents a detailed description of the inherent mechanisms between the Ade, Ledic and Nander clans. The driving force in this world is the surplus or deficit of fat, or energy, which the different entities are connected to in different ways. The aim of Ade-Ledic-Nander, he writes, is to “create a world of situations and actions in a contradictory and discontinuing time-space.”3 At over thirty pages, the manuscript includes occasional red letters and small drawings that refer to the figures in the painting. While the painting could be independently understood through its innate formalistic qualities, Fahlström’s manuscript introduces a narrative context. He also refuses to acknowledge the then-topical divide between art as gesture and art as representation, a position he was to maintain throughout his life.

After years of living in what he described as the “frosty and numb climate” of Stockholm, where his poetry had received little attention, his move to New York in 1961 marked a profound shift.4 The founding of the Moderna Museet in 1958, and the pivotal exhibition “Rörelse i konsten” [Movement in Art] organized by the museum’s founding director, Pontus Hultén, had led to new contacts and transatlantic connections for the Swedish art scene. During the aforementioned exhibition, Fahlström and the painter Barbro Östlihn — to whom he had just gotten married — met Robert Rauschenberg. Although the scholarships that financed their travels were officially for the study of the new American art of Abstract Expressionism, they landed in the center of two even newer art scenes: Pop and Minimalism. From day one they were imbedded in artist circles that included Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, Frank Stella, critic Barbara Rose and characters like Billy Klüver, the Swedish engineer who fostered collaborations between art and science. The couple moved into Robert Rauschenberg’s former studio at 170 Front Street in the southern tip of Manhattan; their neighbor was Jasper Johns. In the blocks around them were other young artists who felt a need to distance themselves from Abstract Expressionism’s headquarters on East 10th Street.

This new context helped define Fahlström’s career shift as a visual artist. No longer in a place where Swedish was spoken, he nonetheless constantly published articles and produced radio and television programs for Sweden, reporting on the American art scene. Influenced by Pop, he abandoned the signifiers of his earlier paintings and started to use comics and other popular culture forms as material for collages and paintings that were more hard-edged than his earlier work. Part of the change was also due to his new, intense collaboration with Barbro Östlihn, who executed much of Fahlström’s work during the ’60s and early ’70s, especially as small collages were transformed into new and bigger versions; her collaboration with Fahlström meant that a new painterly language slipped into his work. Fellow artists Johns and Rauschenberg supported Fahlström’s work and his career developed rapidly. In 1966 he was included in the Nordic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

By the end of the ’60s his subject matter had turned to political systems, world economics and the exploitation of the Third World. Already he had developed strategies for extending the work into the minds of its viewers; in variable paintings like The Planetarium (1963), now part of the collection of the Centre George Pompidou, or installations like Dr. Schweitzer’s Last Mission (1966), figures on magnets could be rearranged according to the intentions of the viewer. However, the white cube of the museum, like the structure of the art market itself, allowed little actual interaction. As a response to this situation the artist decided to use techniques like lithography in order to give his images larger distribution. For example, in May of 1972 he reproduced his World Map on newsprint as an insert for the magazine Liberated Guardian. Still, in an article titled “Historical Painting” published in Flash Art in 1973, he argued that the gallery market was needed in order to reach a larger audience. He explained his new formal strategy: “With the introduction of a completely colored background (in the “Column” series, World Map, etc.), I have gotten into a sort of historical painting where all kinds of data and ideas — historical, economic, poetic, topical — are presented in a unified style. For the sake of clarity, data and interpretations are both written down and depicted visually. Blue colors denote USA, violet Europe, red to yellow socialist countries, and green to brown the Third World.”5

Recently Fahlström’s work has been reintroduced in several art-world contexts. It was mentioned by Mike Kelley in his text “Myth Science” (1995),6 by Catherine David at Documenta X in Kassel in 1997 and by Daniel Birnbaum in relation to “Making Worlds” at the 2009 Venice Biennale. Projects by Mattias Nilsson and Antonio Sergio Bessa have shown that part of Fahlström’s so-called interactive works can be easily adapted to new digital platforms. Öyvind Fahlström’s interest in play theory and his ideas about open artworks, world making, transatlantic experience and semiotic play have great relevance for the contemporary avant-garde; yet his oeuvre is still strongly connected to history and the neo-avant-garde of the ’60s. The entirety of his multilingual universe remains, to a large extent, still to be exploited.