The art world’s recent infatuation with German painting has distracted attention from the emergence of a group of artists contributing substantially to the global art circus. These trends may be related, though: the fetishization of the (painted) surface in the global art market triggered a kind of re-evaluation of sculptural and object-related strategies. So it may in fact not be completely incidental that in the very moment that the appreciation of art and collecting appears to be increasingly about the hunting down and possession of images, that a whole group of artists rediscovers the third dimension to articulate their complex ideas. This is by no means an attempt to create a new Berlin school of sorts, rather a haphazard group of artists who combine a renewed faith in conceptual artistic strategies with multifaceted sculptural and object-related artistic approaches, thereby effortlessly stretching the limitations of notions of the sculptural and the object, its context and inscribed narratives, the possession of it, and the possibilities of interaction with the viewer.

It’s like discovering a peephole somewhere. Coming closer, peering into it, you discover a universe you never knew existed. A little irregularity suddenly exposes the capability to shake the foundations of your world. For example, Kirsten Pieroth isolates everyday objects from their original backdrop and inserts them into a new context. But the irritation this causes in terms of understanding what actually is there generates a whole array of questions that go far beyond that of the original object, its possible functions or its design. Suddenly the object enters a whole range of possible readings, raising surprisingly basic and fundamental questions concerning time and space. Locations, distances, history and geography come into play as systems that represent a set of assumptions that form the backbone of our civilization.

“I regret that a previous engagement prevents me from accepting your kind invitation to dinner at your home, on Thursday evening, September seventeenth.” The title of Kirsten Pieroth’s 2003 show at Galerie Klosterfelde was taken from a letter by Thomas A. Edison: probably an excuse for the American scientist and inventor to skip a social event. This excuse is the starting point for an absurd probing of the quality of invention as such, reflected in letters the artist wrote to file a patent, aligning the lame excuse with Edison’s more famous inventions. A documentary introduction featured a famous autographed photograph of the inventor power-napping on a workbench. His signature on the picture was forged — however, as if to prove the contrary, the centerpiece of the show, Edison’s Workbench, reconstructed by the artist, bears the signature, of course executed by the artist herself. The myth of artistic creativity is reflected in that of the inventor’s genius, simultaneously undermining prevailing concepts of truth and authenticity. Instead the artist humbly proposes a more subversive and critical narrative, supported by the physical presence of the workbench, that lends a subjective form to the idea of intellectual property as such, and the act of making history.

Apparently the third dimension is required to successfully render a social concept as a possession, especially in times of immediate accessibility of digitized information. The availability of anything as an image in turn renders sculpture an authority of the real. A project by two Berlin-based young Norwegian artists, Jan Christensen and Øystein Aasan, turned the Oslo Central Railway station into a huge sculpture by covering a large part of the glass facade with the adaptation of a quote by Berlin art critic Raimar Stange: “Politically encoded surface.” Meant as a completely unspecific statement, apparently mocking interventionist strategies, the reverberations of the piece led both artists individually to new works dealing with issues of appropriation, site-specificity and architecture. Christensen embarked on an experimental wall painting spree, developing large-scale installations that shamelessly appropriate and rework artist trademarks — like the stripes associated with Jim Lambie or Bridget Riley he used for the project room at the Irish Museum for Modern Art. Øystein Aasan continues to question notions of authenticity and concepts of intellectual possession with his bootleg pieces: sculptures that function as displays for stacked CDs of unauthorized recordings that are illegal, but extremely popular among fans of particular rock bands. The formal language of the sculptures draws on Russian constructivism, and their contextual concepts of common possession offer a historic twist to the whole narrative of encoded surfaces and possession of culture, as well as the discourse of presentation and representation.

A related interest lead Natascha Sadr Haghighian to involve the context into the presentation, letting it basically represent itself. Her first solo show “The horned owl’s diseases and their significance for its re-naturalization in the Federal Republic of Germany”(2003) consisted of Johann König’s seemingly empty gallery space. Invisible birds, uncannily attached to the presence of viewers, emitted audible attempts to escape. A cracked but not broken gallery window bore witness to the efforts of trying to flee the white cube. Sensors in the doors triggered sound-loops of an increasingly panicky flutter of a bird, circling the speakers, even crashing into the windowpanes. The birds’ panic was tied to the visitor’s presence; as soon as the opening bustle was over, the frantic bird-cage scenario subsided, reminding the leaving visitor in a very poetic way of the linkage between ideas of global culture and local realities, tensed up by the ghost of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds.

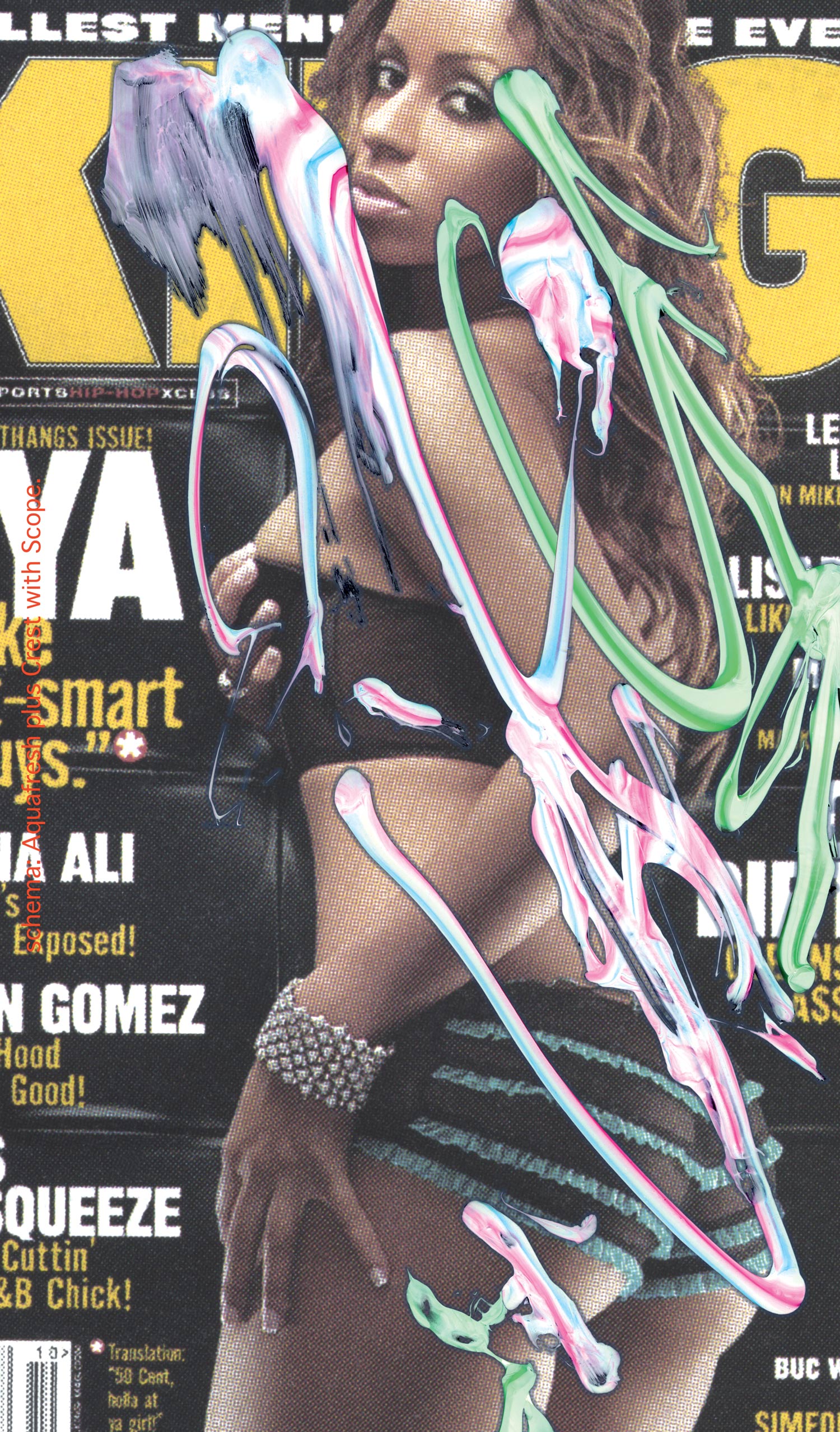

Departing from a post-minimalist formal language, Michaela Meise’s sculptures function on a completely different level, displaying elements that seem to stem from coincidence as well as from construction. Drawing from sources that range from the aesthetics of minimalism to the mock-minimalism of Heimo Zobernig, they appear precarious and precious at the same time, simple and impenetrable. Geometric, abstract, yet sketchy, they stubbornly retain an air of ambiguity, an out-of-placeness, even if apparently contextualized with stuck-on photographs of, e.g., female celebrities. But does it all add up? It is the precisely proportioned installation, rivaling with the dissonances of content and form, that makes her works resonate. Her sculptures acquire their unspecific reading by the diverse elements forced together, like Black Laundry Cube (2002), a wooden cube featuring a photograph of a rally of bare-breasted members of the leftwing lesbian group Black Laundry, sporting Palestinian scarves on Tel Aviv’s Christopher Street Day, probably not gaining much support from Palestine.

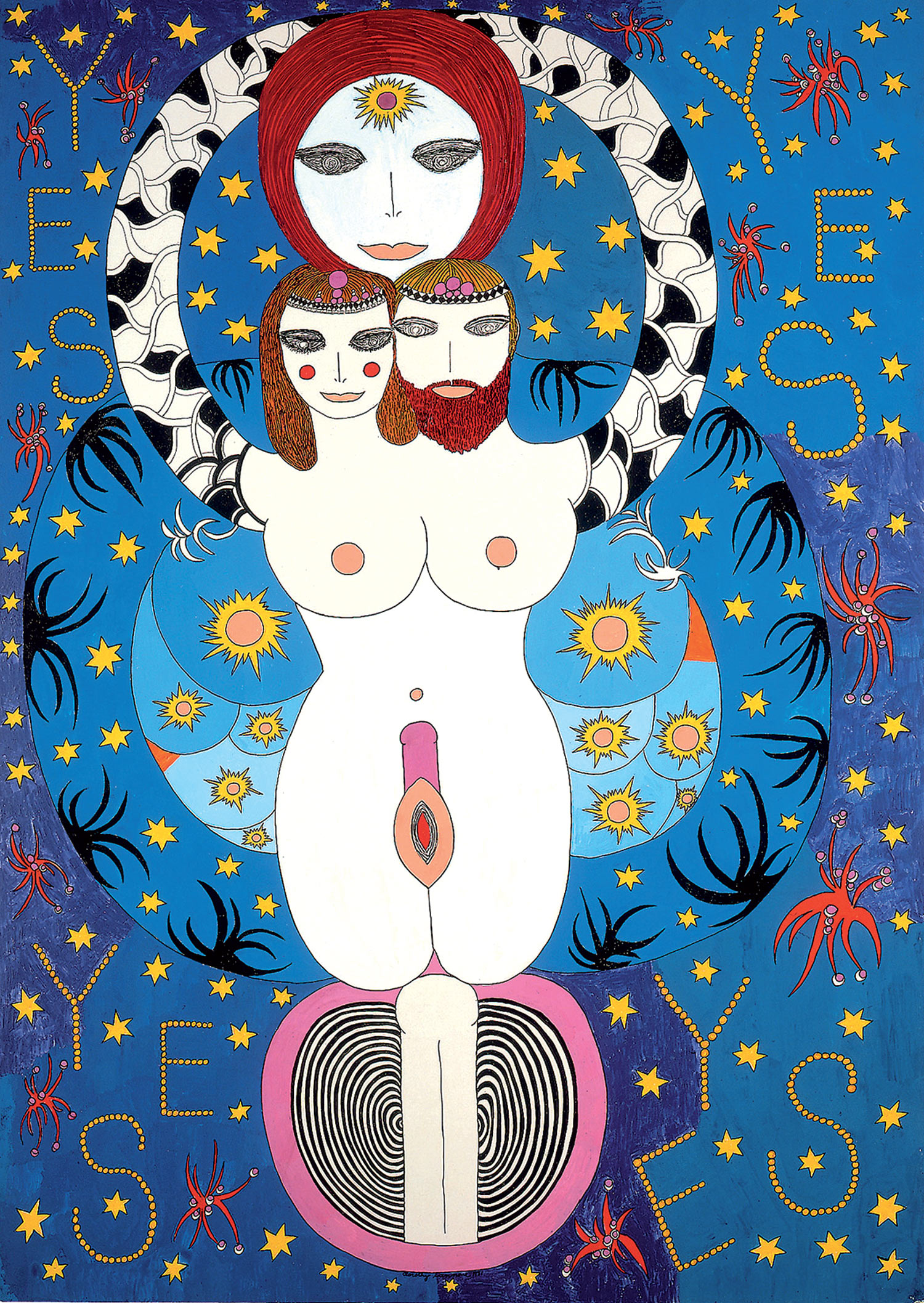

Gone (Collection of Once Was), from 2006, on display in January at the Berlin branch of Peres Projects, is a huge installation comprised of large-scale collages of found images, and a room size sculpture by Kirstine Roepstorff. An oversized replica of an empty museum display case, propped up by stilts, hovers menacingly over a collage composed of found images. The missing contents of the display case, the very sources of our culture, are about to crash into a splatter of image culture, where everything has the same relevance, has become mere surface, without any conceptual power or idea content at all. It portrays the doomed idea of a common identity constructed entirely on the concept of loss.

Common identity is also a recurring theme in the sculptural fabulations of Björn Dahlem. His most recent show in Vienna at Engholm Engelhorn, the “Homunculus Saloon” (2006) explores notions of the construction of an ideal identity. Rooted in German Romanticism’s quest for deeper meaning, and equipped with laconic humor and panache, his art reflects the innermost structure of the cosmos as another model of the romantic Seelenlandschaft. The landscape of the soul, that artists like Caspar David Friedrich were preoccupied with, contemplated the imponderable profundities of the inner self. But in Dahlem’s eccentric wood lattice sculptures the apparently rational approach succeeds in metaphorically constructing identities, where the uncertainty principle is the ultima ratio and the hyper-psyche reaches a perfect state — where all inconsistencies are flushed down the black hole. Establishing the apparently all-too-human flatness of the supposedly endless depth of the universe, Dahlem’s sculptural and architectural constructions existentially question any concept of science and rational truth.

Just as expansive — but with a different concept of narrative, Michael Beutler’s on-site sculptures gain their immediacy by relating directly to particular architectonic situations. Rather than approaching these systematically, Beutler subjects himself to an idiosyncratic experimental process, incorporating playful rules, homemade machines and standard DIY techniques, following a sequence of mutually conditional decisions through to the very end.

The results frequently bear the marks of the artist’s interest in conceptualizing his production processes, connecting his observations with the particular qualities of his every-day building materials, bending their intended use to lyrical-sculptural interventions with often ornamental structures, often with surprising static qualities. Maybe most known for his piece Next to Center (2005), a site-specific sculptural installation presented at the Frieze Art Fair, he made use of the resources found in and around the fair environs, reacting to the fair’s internal grid structure. Beutler succeeded in constructing a social structure, reflecting utopian ideals in architecture. His pragmatic view of creative processes, emphasizing craft and the closeness to the material, explored an alternative way of inhabiting a rather restrictive situation, resulting in a playful interrogation of private and public locations.

“Besitzarbeiten” (Property Works) is what Florian Slotawa called a series of his early pieces, created entirely of objects in his private possession. Inspired by a genuine interest in sculpture, motivated by an early infatuation with the conceptual art of Lawrence Wiener and Hanne Darboven, and furthered by a deep distrust towards adding more objects to a world already overflowing, the art student first moved all of his belongings into his studio, using them to assemble his first sculptural works. In an ongoing ping-pong game with his photographic ambitions to catalogue his possessions, he has continuously expanded the context of his assemblages, from his own property that he exhibited as a whole (and sold to a private collector) at his show at the Kunsthalle Mannheim in 2002. Since then, while the sculptures made of his possessions were on display, he has utilized the property of museum staff and the contents of museums and hotel rooms where he has stayed. Only temporary transformations, these works remain as documentation. As the artist prefers to work with what is already there, the scope of what is available has extended to a point where his latest sculptures are produced using elements from Ikea shelves. These industrially produced boards are ubiquitous materials, available on three of the world’s continents, requiring no further refinement, ready to be stacked into modernist, cubic sculptures, according to the artist’s plans, held with a lashing strap.

By stacking her whole oeuvre on a standard transport palette, Haegue Yang produced Storage Piece (2004) — quite a tease for the interested viewer. And a surprisingly substantial physical presence, the wrapped and boxed works as such acquired a quasi-sculptural quality. The artist included an inventory counting up the odds and ends of the pieces, as mere materials, like a recipe, combined with a recording of a text by the artist on her personal attachment to them, the concepts of possession, and recounting ambitions and anecdotes of the production of some of the pieces included. By opening her work to a reading that included the personal, maybe less noticeable and ephemeral notions of the everyday, this stacking piece acquired a relevance at once poetic, funny, private and witty. It is not only recontextualization or her anti-spectacular strategy, but her very unique sensibility, purveying a refreshingly funny but also slightly melancholic sense of alienation.

The idea of the sense of alienation brings us back to Kirsten Pieroth and one of her most beautiful pieces: a puddle. Collected in Berlin, she brought it to Albania for the 1st Tirana Biennale, exhibiting it on the floor of the Chinese Pavilion. Visitors passing it would try to walk around it, or raise their heads to the ceiling, looking for the leak in the roof. Many never noticed and just waded through, spreading the mess from Berlin to Albania, and to the rest of the world.