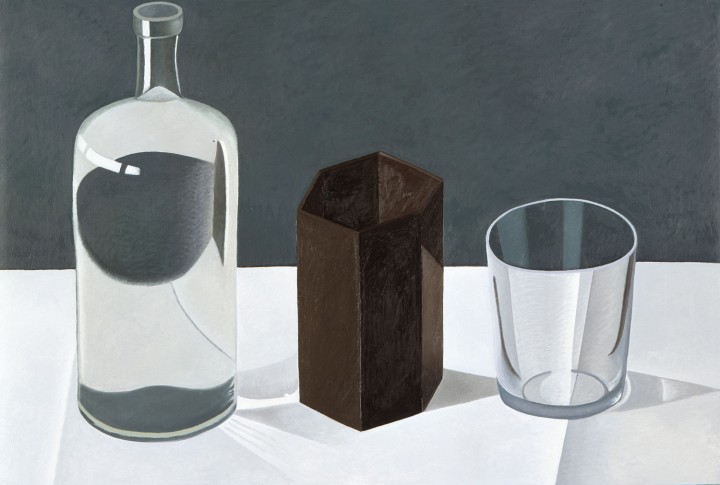

Molto grigio con blu is one of a series of paintings done between 2001 and 2003 that mainly depicts glass objects. At the center of the painting there is a large, flat bottle, two-thirds full of water. Arranged around it are a glass and a blue bottle of vegetable oil with a black stopper that appears to have been made originally for a pot of glue. On the other side, a smaller glass stands on a little upside-down plastic yoghurt cup. The background is gray. The blue bottle stands partly behind the bottle of water, partly deformed by it. The scene is closely framed. This painting represents a small revolution in the oeuvre of Nathalie Du Pasquier (b. 1957, France; lives in Milan); it inaugurates the process of progressive abstraction of her depicted subjects/objects. Paradoxically, through the years they will never lose their integrity. They do not undergo a transfiguration but rather a progressive semantic reduction. Du Pasquier holds on to her conviction that a painting is an object in itself and not a document about reality. However, she never contradicts the identity of the depicted images. She blatantly represents real objects installed in front of her, like a little set — the choice of objects being an occasion to assemble elements of interest.

The idea of “frame” epitomizes Du Pasquier’s practice. Her painting is intimately concerned with the significance of structure, composition, status and time, all of which the photographic term “frame” includes and expresses. For the artist and her work, time is the essential factor: the time she spends looking and the time that transforms what she observes. She generally uses what is available in the atelier. However, months may go by before these forms find a definitive place in a composition. She moves the objects again and again until the mise-en-scène appears to be plausible and fit for reproduction on the canvas. With the aid of a square sight in the middle of a sheet of cardboard, she peers at the arrangement, considering even the most unlikely views attentively. She also calls upon the camera during this phase of scouting and assessment of reality. She is seeking the instantaneous vision of that instrument, the vision that she will fix in her mind before approaching the painting surface.

She has no interest in rendering the relationships or the stories that are inevitably latent in the pictorial group, just as she does not care to stylize them. She has no fear of appearing to be decorative. Her only mandate is to paint well. This does not exclude her awareness of what she immortalizes — for example, the conscious intent to fix what observers normally do not see. This was the reason for dwelling on transparent subjects, to perceive the objects behind the glass. She does not interfere with what she sees and does not attempt to manipulate it. What pleases her about the transparent condition of glass is perceiving the natural transfiguration of objects beyond it. The mind recognizes the objects behind the glass, but the artist focuses her mind on how they are seen and not on how they are recognizable. That is why she has never made a theoretical statement. What she does and the reason for what she does are in the sphere of the inexpressible. She has painted over-scaled objects many times without creating a hierarchy among them. This is her way of detaching them from the idea of naturalism and emphasizing how they relate in time. There is more time around large objects because they demand more time to be depicted and, likewise, require more time to be observed.

Often artists feel obliged to challenge the traditional methods of representing the world that they find obsolete. They even go so far as to believe that their mission is to change these methods of representation. So many ways of representing reality have been assessed that the space of action for an artist has been totally mapped. However, painting exists even beyond the techniques that have identified or qualified it until now, and nothing has been invented that can really substitute the quality of oil painting. This is another reason why Du Pasquier is fundamentally devoted to painting. She wants to be able to repeat the traceable experience that comprehends the idea, the vision and the finite space of a two-dimensional image. Operating in this way, she does not feel at all isolated from the world or the great questions that agitate and inspire man’s life every day in the fields of sociology, anthropology, philosophy or even science and economics. There are no scales of relative value between the utensils, forms and materials included in her artistic project and depicted in her paintings. They originate in semantic areas that are often considered contradistinctive — zones that are fraught with risk but feature unexplored sensory qualities. So far so good. However, it must be said that Du Pasquier has never indulged in reckless postmodern sprees in which elements are assembled and painted without rationale or reason. On the contrary, she has always taken care to represent the elements for what they are.

With respect to the history of the still life, Du Pasquier emphasizes a desire for objectivity over sentiment. Her continuous attention to the plastic structure of form and space confine the work to the existing limits of an absolute construction. Her approach to color, intended to modify the rational component of the pictorial image by introducing light values and the delicacy of sentiment into the structure is quite different and, in fact, extraneous to her work. Note that the simple, or occasionally complex, objects gathered together in her still lifes never lose their real substance. They are never merely ghosts of her memory.

However, the paintings are apparently becoming more abstract. She has taken this direction because she no longer wished to hear the comments about the nature of the objects she had selected for so many years. The objects were also vulnerable to symbolic interpretation. Her motivation was a strong desire to eliminate what little narrative remained in her pictorial compositions. She has always loved the mutism of abstract paintings, which are what they are. If someone depicts a basket, a glass or a stapler, an observer always wonders the reasons for the choice.

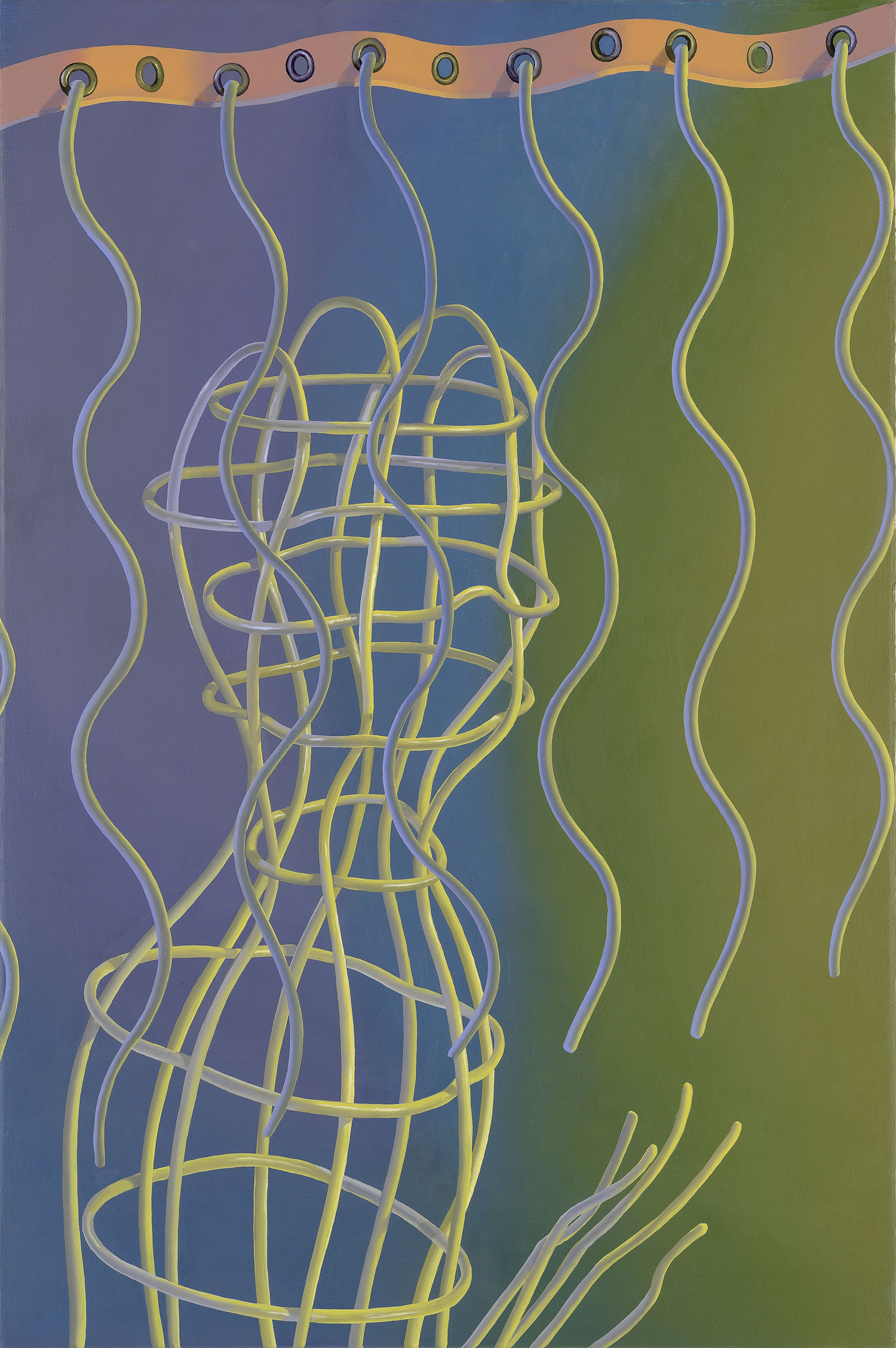

Since 2003 she has adopted the strategy of constructing and representing abstract things. Her work is now divided into two phases, construction and painting — but the silent moment of painting is still safe! Du Pasquier has resumed an operational procedure she inaugurated in the 1980s when she also worked as a designer. The constructions have independent personalities and cease to be merely models. They may be exhibited in shows where there are paintings on view. Obviously, they are never shown together with the paintings that represent them, but they participate in completing the theme of this type of architecture. They are components of her work as it proceeds, expanding, changing and discovering new modes for speaking about these imaginary spaces that serve only to make beautiful paintings and nothing else.