originally published in Flash Art International n°186, 1996

This discourse disturbs the gaps occupied by an articulate enunciatory practice that poses a challenge to contemporary thought. It is a place where the supercessional language of modernism is peeled away and made mute in the stereophony of clashing tongues. This in many ways represents the fraught encounters between cultures, in that juncture where furtive glances are exchanged in the sprawling market place of modernity, which in turn motivates the possibility of the plural in the discourse of cultures.

This possibility of the plural is what has come to define the postmodern, and its celebration of contingency, fragmentation, and rupture (which defy reconciliation), events that are profoundly anti-Hegelian gestures. They reinforce the incredulity of grand narratives — and indeed of all metanarratives. Such objections represent not just a mere critique of systems, nor are they exclusively internal philosophic objections to what now strikes us as the myth of the progressive dialectic of the Enlightenment Spirit.

Many of them are motivated by ethical-political considerations that address the complexity of modern experience. Anyone who has experienced the 20th century in places where there has been much violence, barbarism, genocide (both as products of colonialism and post-colonialism), can scarcely avoid being incredulous about a narrative which casts history as the progressive realization of freedom.

If art then is a practice of freedom, we must equally insist on a subjective critical practice which dislocates the ingrained cynicism and prejudice that mars the speech of the so-called ‘other,’ which sequesters its agency outside the time line of history. We must insist on the contingent analysis of all cultural discourses that claim this freedom exclusively for themselves. Following the discourse of power that defines colonial relationships along the binary logic of Us/Them, Center/Periphery and which also sees the contributions of the dominated to culture as either inconsequential or supplementary, one cannot avoid being suspicious and skeptical of the possibility of achieving some kind of reconciliation with reality through speculative comprehension.

In the contest of history, Africa is a lost continent to many, a modern day Atlantis, elusive in the vicissitudes of 20th century cultural narratives. To locate Africa as an arbitrary soundbite in these narratives is to regulate its commensurability. Today African art, and most emblematically contemporary African art, exists as a dehistoricized territory teeming with fictive narratives. As the critic and artist Olu Oguibe has vividly written, this is a contested territory “where the contemporary African artist finds herself locked in a struggle for survival, a struggle against displacement by the numerous strategies of regulation and surveillance.”1 It is a territory where the West has assigned itself the power of sanction and legislation while inscribing African subjectivity in “the befuddled corners of obscurity and rudimentary episteme.”

In the frenetic events of late 20th century critical summations, Africa also remains, as in the past, a territory of the imagination, contradictorily occupying a place of origins and lack, a forest of excessive and aberrant signs that troubles the cultural logic of the modernist project. But for those in search of genuine knowledge of this area of contemporary cultural production, it is these fictive histories that have come to repeatedly circumscribe the potent artistic activities of a young generation of African artists. Those histories turn their practice into colonies of perversion that are magnified and projected through the peculiar lens of occidental desire and its almost insatiable taste for the exotic.

Turning to the practices of contemporary African artists and their relation to critical art discourse, we are jarringly confronted with questions that dance around the possibility of an autonomous post-colonial enunciation. It is a challenge made keen in a set of questions posed by Homi Bhabha when he asks “How is historical agency enacted in the slenderness of narrative? How do we historicize the event of the dehistoricized? If, as they say, the past is a foreign country, then what does it mean to encounter a past that is your own country reterritorialized, even terrorized by another?” Western attitudes willfully ignore or refuse to engage these questions, choosing instead a regulatory distance from which to pay lip service to a notoriously patronizing relationship.

Reading the careers of the eight contemporary artists discussed later in the text, who by accident of origin are African, what becomes so clearly articulated is the broad spectrum of interests and philosophies evident in their maturation as artists. These interests and philosophies slip away from the received and prejudicial notions of Africanity (read: pre-modernity) with which the western establishment endows art by Africans of any period or generation.

In these works, scattered and subsumed within the prime networks of many critical regimes, what we encounter are acts that aspire to agency, the desire for an extensive and complex elaboration of what it means to live and work as an African artist in a uniform environment that refuses their value through recourse to primitivization. The debates around which their work is centered contend for and aim to prise open a space that can interrogatively turn the subjective agency of the depersonalized into a fruitful discursive activity. Thus, they arrest the historical contingency which hegemonic dehistorization imposes and turn it into an event of disruption and empowerment.

Today contemporary African art is very much in the news. More and more exhibitions are devoted to its artists. But there is something peculiarly distasteful about exhibition opportunities that grant almost sixty percent of their time and space to artists from the collection of one Swiss collector. Jean Pigozzi’s collection which, with characteristic bombast and inelegant immodesty, bills itself as the largest collection of contemporary African art, has made the past few years a template for the abuse of privilege and access. Administered by his curatorial henchman André Magnin, the collection privileges the kind of art that typifies what might be called Outsider Art setting up a dichotomy between the work of young and innovative artists and the so-called untutored artists.

As Valentin Y. Mudimbe has pointed out, the colonizing structure has resulted in a dichotomizing system and with it a great number of current paradigmatic oppositions have evolved: “traditional versus modern; oral versus written; agrarian and customary communities versus urban and industrialized civilizations; subsistence economies versus highly productive economies.”

It is particularly pertinent to write about this generation of African artists without arresting the comprehension of their work through the regulatory devices of institutional and curatorial framing. Such devices privilege this dichotomy in historicizing Africa’s contemporaneity. The great temptation would be to continue to write on the practice of African artists in terms of arguments that struggle to untangle their individual aesthetic projects from the carnivalesque, as marginal inscriptions written on the tattered endpapers of modernity. However, what demands enunciation — between stereophony and muteness — is that wide space of unmediated desire in which many contemporary artists from post-colonial cultures search for a voice.

Bili Bidjocka slyly steps out of the muteness and stereophony of a false African speech and enters the dismal wreckage of the modern metropolis. Today it seems a commonly accepted practice among contemporary artists to show works of art that address social, political and economic conditions — an end-of-century condition implicit in most postmodern art.

If most viewers feel increasingly alienated from this art, that supposedly ignores the aesthetic idealism of prior art, it is because, as many socially and politically engaged artists see it, those viewers need to be weaned from such idealism. Bili Bidjocka however, attempts to recover the vital aspects of these two conditions by mobilizing the historical conjunctions and the competing demands of the social and the aesthetic.

Born in 1962 and resident in Paris since age twelve, Bidjocka is a conceptual artist whose work is positioned on that vital and contentious boundary between modernism and postmodernism. Mobilizing the political and social dimensions of identity, and locating his practice on philosophical inquiries into accepted conventions of artistic activity and representation, he pluralizes his forms and materials by turning to discarded objects already touched by or imbued with human hands and presence.

In a recent work titled Explicit Lyrics (1995), Bidjocka appropriates elements of rapture to address questions of emptiness and absence, of beauty and its limitations. To make his work, Bidjocka, like Olu Oguibe and Georges Adéagbo, exits the confines of the studio to probe the fissures and submerged gaps of modern material entropy. A poet of obsolescence, he plunders the streets of the metropolis, rescuing discarded objects and resituating them in new performative roles. Dislocating the primacy of site and location, the works take on a new life, new role, and new meanings. The found objects serve as referents for the outside world, its memories, its absent and diminished bodies.

Caught between memory and absence, in the interstitial space opened by loss, the emotional effects of his paintings and installations are resolved in that space where personal experience can be invoked abstractly enough so as to be seen as the experience of another. Bidjocka appreciates that it is in the instance in which we feel empathy for, and share the pain and history of others, that we come closest to understanding our own pain. And yet, the profusion of eggs and shaped-ball arrangements in his paintings and installations suggest desire for beginning and renewal.

Olu Oguibe, born in Nigeria, works with careful deliberation. Metaphors and symbolism are ruefully deployed and put into jarring but ironic juxtapositions in works fashioned both out of cerebral dispersions and concretized employment of materials in an attempt to rupture modernist notions of aesthetic inwardness invested in objects that reek incompetently of beauty. Here two polarities converge.

On the one hand, Oguibe primes his sometimes disputing productions with a cool distanced rhetoric that plays on minimalist iconography. On the other, his works unpack a range of topics and issues, mixing their volatility and tensions to deracinate modernist exclusivity and possession of the right to discourse.

Untitled (1994), an installation of a mirror in a heavy gilded frame that is roped off at a certain distance from the viewer, suggests ideas about portraiture, self-observation, presence/absence, and framing as a metaphor for the reified masterpiece object and the commodified subject. Another untitled work, a gleaming toilet bowl friezed with a shower curtain made out of the British Union Jack (the Empire’s mascot), evidences the false stiff upper lip that decorates the stoic façade of a pristine environment while revealing the abject nature of waste contained within.

One can argue that the hegemony of the British empire also appropriates this role in its colonial projects by posing its brutal annexations of overseas territories around the argument of a civilizing mission. A reading of this work takes the obvious route of invoking Duchamp’s urinal. But this is merely an incidental art historical reference. The underlying structure of this piece within Oguibe’s oeuvre is of a more mediated and engaged interrogation of structures of authority and domination. Above all else, Oguibe makes work that is strikingly divergent from the concerns of postcolonial cultural ideology and the cloying charm of oppositionality.

Houria Niati was born in Algeria in 1948 and has lived in London since 1979. Since the early ’80s, she has been exploring the Orientalists’ images and constructs of Algerian women, particularly in the work of French painter Eugène Delacroix and, generally, in postcards and photographs from the French colonial period in Algeria.

From the terror and fear she experienced as an incarcerated child during the Algerian’s war of resistance against the French, Niati’s work brings a palpable disgust towards the distorted French colonialist images of Algerian women as exotic possessions, erotic objects and submissive creatures. Her work is also critical of the oppression of women in today’s Algeria and to the feeling of betrayal by the Revolution’s male dominated leadership after independence.

Still, complex as her work already is, Niati invests it with multiple sources and artistic traditions, which not only assert her Algerian identity, and her pan-African devotion, in her use of West African decorative elements, but also — like her western colleagues — her claim to styles, issues, influences and interests relate to her experience as an African artist living in the West.

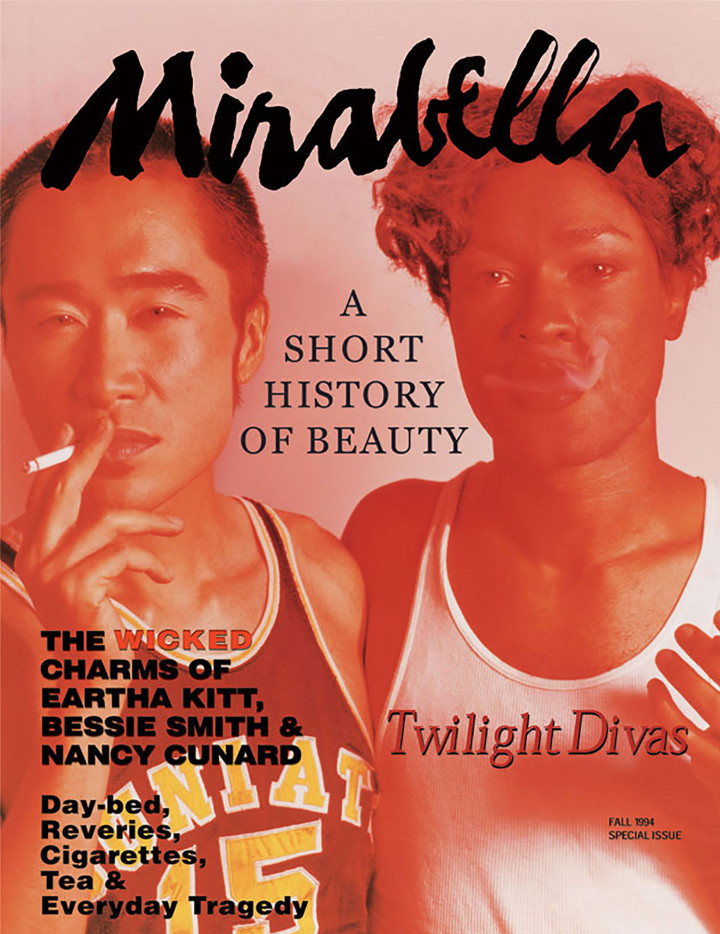

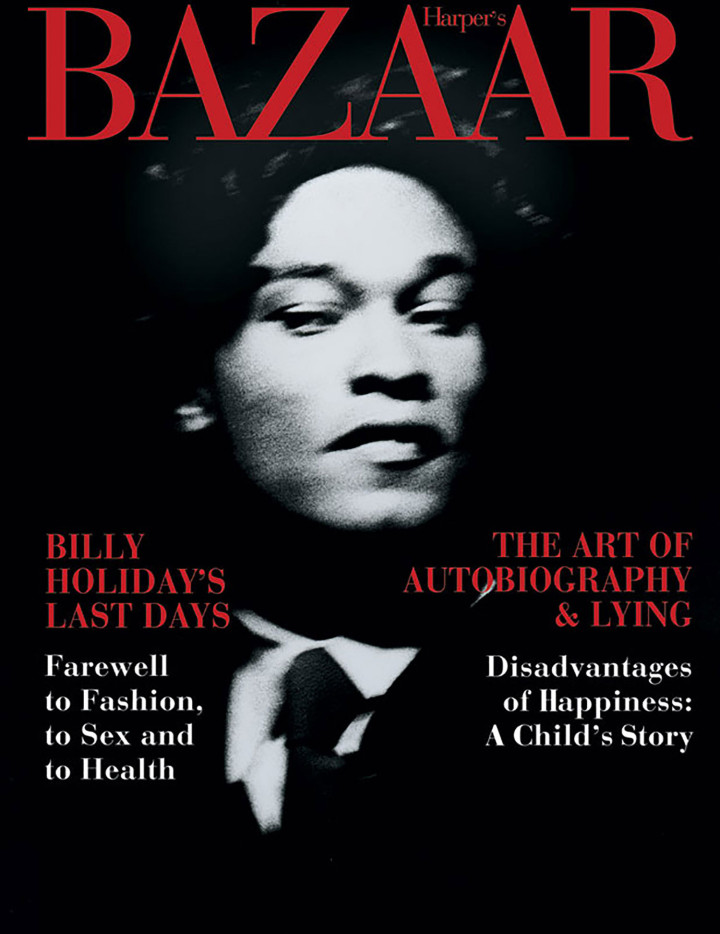

Iké Udé’s work uses photocopies, photography and text which the artist then intercuts with commentary and turns into movie posters and magazine covers, or simply agitated walls plastered with wayward images pillaged from fashion magazines. This is appropriationist art of a high order.

In his recent multimedia installations (video, photography, prints and performance), Udé uses that most traditional of genres, self-portraiture, meticulously disguising and photographing himself in different identities (waif, dandy, supermodel, masquerader, etc.), which he then renders as virtual movie-posters or magazine covers such as Vogue, Glamour, Town and Country, Harpers Bazaar, Conde Nast Travelers, Parents, etc. Vivid commentaries such as “Who is Afraid of O.J.” and “Hysteria over the Death of the Noble Savage” are added as cover copy to further chart the territory of power and dispossession. The artist appropriates and subverts the magazine covers and posters that provide the blueprint for his interventions, activating a discursive platform to engage sociopolitical issues.

Bound at first glance to the performative space of the western drag culture, Udé’s ambivalent narratives of desire and manipulation are instead connected to “Adanma,” a contemporary Igbo masquerade performance genre in which men impersonate feminine characters to gain access to wide ranging discussions about gender identity and politics and to co-opt and control women’s agency. Udé, while replicating impersonation and masquerading from an African context, extends into territories of the Western media, thus deconstructing the formation of an image of the African as exotic object and exposes the fantasy embedded within the rigid limits of history, identity and difference.

Folake Shoga’s video work and installations embody a rather tremulous uncertainty, though a more fruitful encounter with them reveals the artist’s sureness of vision. Working in the gaps that doubly marginalize and glorify women of mixed race descent as strange hybrids and exotic objects, Shoga, born in Nigeria and resident in England for the last twenty years, has instituted a contrapuntal and reflective take on issues of race and femininity.

In order to trace the elusive cartographies of mixed-race women’s lives, their desires and celebration of difference, the artist works from the ground zero of representation by using her own body. She projects it into those unexplored territories of the psyche that refuse naming while still quivering with knowingness. Her experimental installation, Like Something Not Very Concrete (1994) employs video, film projection, found furniture and sound to furnish an environment in which viewers, in their experience of the work, become integrated into the work’s setting as co-conspirators.

This dialectical work, set in a temporal and spatial interdependency, uses the traditional film technique of quick cuts and edits, as well as narrative fragmentation, to intercut and splice footage and build dense but still insouciant forests of signs. In Shoga’s work, it might be possible to probe attitudes posed around the confrontation between technology and tradition in order to arrest and iterate the probable emancipation of contemporary African art from academic formalism.

The scars of Angola’s recent civil war pervade the multimedia installations of Antonio Ole, through its corrugated iron walls, its scrap metal parts, its cinders and bone fragments, its wrecked boats, its brick arrangements and lurking stuffed crows. As a site of desolation, this seemingly empty scenario enacts the blindness and deafening silence that Africa has experienced within the New World Order of things; but it also unveils those inner dwellings where the distance between the ‘other’ and the self finds its resolution. For this is not a place empty of people, and the emotional impact which this devastated scenario incites in viewers might well reflect the fact that the urban wasteland is not the exclusive territory of the so called Third World countries. The compelling photographs of Angolan survivors that accompany Ole’s installation indeed look as much to the wreckage as to the viewers.

“If at a previous stage my work focused on a survey of the traditional Angolan culture, extracting from there new signs, at the present moment I am more interested in facing art in a more comprehensive, global, multidisciplinary form,” explains Ole, “where the aesthetic play develops out of elements linked to collective memory in general and out of a certain critical capacity which seems to me to be necessary to reactivate in people.” Despite their conceptual sophistication, in the experience of Ole’s works, sensation takes precedence over thought, and since the driving force of the artist is a compulsive desire to grasp reality, we can say that he has a tragic approach to that reality which he endeavors to communicate, and that his tragic urge outgrows an emotional effacing of boundaries.

The interiors, self-portraits and landscapes that Oladele Bamgboye renders as photographs, made by performance and props standing as repositories for cultural symbols and stereotypes, are also searching for a presence. From memory and identity, both blurred among the lights and shadows of cultural relocation, Bamgboye presents his subjects in their substantiality. He refuses, however, to idealize them, trying not so much to enthrall the real thing, as seeking to render the reality of the thing, its existence, over and above its circumstantial characteristics, so as to keep no more than its biting essence, as in those shots which show a wound in the genital area of the artist’s body.

The artist departs from the literal representation of its subjects to rediscover them in a more real assault on the real, to create some sort of intersubjectivity with the viewers where the emotional and the speculative are bridged. In this way, Bamgboye avoids any fetishizing, any availability as object, deconstructing on the one hand the sexuality projected onto the black male body and, on the other, demythifying his own role, as photographer and sitter.

A recent installation by the South African artist Kay Hassan, The Flight (1995), a mise-en-scène that alternately compels us and puzzles us, is another ruptured location of emotional intensity. In encountering the work on the floor, we are confronted with a made mattress, some packages and parcels, old suitcases and a few bundles. There is nobody there except the viewer, but each of these objects has a personal feeling, a private story to tell. On looking more closely, by the bedside, we find an open bible, a bottle and some foodstuffs on a beat-up suitcase. These might be the stuffs of the emigrant, of the displaced, of the relocated, of the political refugee, of the homeless, of anyone used to living on the move.

We could not say from where or in what manner these obvious, familiar, direct objects came to be as they are. We may sense the absence though; and the anxiety and the pain. We may even come to realize that we are invading the place of someone else. These objects trigger in us the memory of an experience that is not our own, of a condition we would rather forget. But we can not evade their meaning: they are the badges of a culture always searching for a home.

Of course, other contemporary African artists, living either inside or outside the continent, would have been equally pertinent in an account confronting and exposing the self-defeating agendas of those who continue to profit from the farcical idea that contemporary African art is an exotic territory of untutored craftsmen ready to be occupied.

Amongst others, Ouattara Watts, Touhami Ennadre, William Kentridge, Willie Bester, David Koloane and Rotimi Fani-Kayode have already proven them wrong. And the big wave moving in, including Lubaina Himid, Candice Breitz, Joachim Schönfeldt, Fernando Alvim, Kendell Geers, Yinka Shonibare, Odili Donald Odita and Belinda Blignaut are already engaged in a practice aimed at disrupting entrenched Western structures of reference.

from Flash Art International n°186, 1996