Bill Arning: In my time at MIT, I was always really grateful to be in a place where the bulk of the efforts and intelligence of amazing people is focused on improving the future. What was your experience with being around scientists and science historians at MIT?

Matthew Day Jackson: MIT was important for many reasons, the most important of which was being in a micro-culture that values the balance between thinking and making. MIT’s motto is “Mens et Manus” [Mind and Hand]. It felt good to be in a place that values the work of ones hand in direct relationship to the thoughts in their head. In contemporary art the working hand is perceived to be disconnected from a brain that thinks. Being at MIT also taught me that part of my future might have a place at a university.

BA: How so?

MDJ: What has started to shape a vision for a contemporary arts education is a fascination with the culture of physics before WWII, which lead to the “Gadget” [first atomic bomb.] Also, learning about Draper Labs, reading about Oppenheimer’s tenure at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, reading your thesis on Geyorgy Kepes, and NASA (Mercury-Apollo.) The thing that all of these shared was a level of intensity in thinking and making, and also learning through the process of both. It would be an institute, within a university, which would invite non-tenure “professors” from many different disciplines within the creative field to work professionally and independently (this would depend on the individual.) While at the institute they would be expected to deliver a series of talks to discuss whatever they thought young people should learn. The students of the university would get to see professionals working (writing, dancing, painting, whatevering) and perhaps become involved in projects that the invited “professional” would like to accomplish while in residency. The end of these residencies would be punctuated with a performance, a show, perhaps a selected reading or publication. Hopefully though, it would include the possibility of failures, digressions, misfires, so that students would get to understand these as well. There is much that doesn’t work. Each of the people invited would be a cross section of the creative field, but hopefully “curated” so that there would be the possibility for panel discussions or, perhaps, collaborations. It would be part think tank, part atelier, but share little with Bauhaus education, which is the antique model for teaching art now. The thing that would mirror my time at MIT is that the “professionals” invited to the institute would have free access to the many branches of the university.

BA: Buckminster Fuller was a big touchstone for both of us working on the show “The Immeasurable Distance” [MIT and Contemporary Art Museum, Huston (2009),] and seeing Fuller’s “Starting With The Universe” (2008) at the Whitney Museum with you was a great experience. With Fuller there is also the embarrassment of watching him tell these self-aggrandizing stories again and again; however it does occur to me that it is precisely Fuller’s lack of shame about saving the world that makes him so appealing today. Does Fuller embarrass you? Does he make you want to be him?

MDJ: I am part of a generation where “cool distance” is the currency for posturing one’s ideas. We were raised by people who believed that they could change the world, and our natural reaction is to gravitate towards irony and not to believe in anything, particularly in our individual selves. There is something fucked up about thinking that saving the world is embarrassing. It takes a remarkable amount of bravery to even hint at thinking that one could do good and to follow their dreams. As far as Bucky [Buckminster Fuller] is concerned, we all know that there is a bit of myth building, in which Bucky played a part, just as all artists do. The thing that I find inspiring about Bucky is that he dared to create a formal structure for his ideas that were uninhibited by the increasing specialization of everything around him. My favorite artists/figures are those who have dared to create new ways of expressing themselves, which in turn gives us permission to dare to think differently. I have no desire to be Bucky. I am a palimpsest of influences that are beyond my control.

BA: There are so many aspects of your work that deal with things that happened before you were born, that still seem to belong to the future — like manned space travel. How does being a baby of the ’70s affect your view of the future?

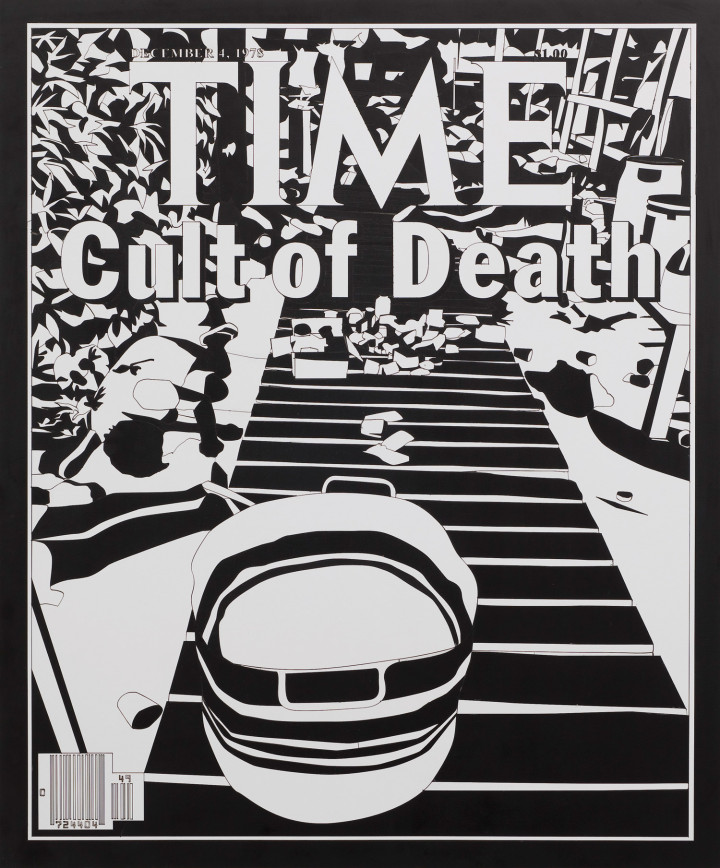

MDJ: I am the product of thousands of generations, as is the society that I live in. I am part of a generation raised on low expectations, melancholy and disillusion. Every cultural event that I witnessed in my younger life revolved around grunge, punk and metal. Underachieving as cool, fuck you, and death. I want to be clear, I love it all because it gave me a foundation from which to build what I am building now. I still seek louder and faster, and I am building a formal structure that is unique unto myself, in a search for being truly fluent in expressing myself. This fluency will never be achieved; I believe I will die trying. History does not live in the past. History lives in the present. I see things this way: nothing dies. Meaning transforms through time and is constituted by the things around it. Meaning is in the reflection of the thing, not in the thing itself; meaning is in how it affects the things around it. Just as the event I am speaking about is the reflection of all of the events that led up to it. This is not to say that there is nothing new. I feel that everything is always new as the recombination of material, meaning, form, etc., presents new forms every day.

BA: You will be having a baby before this interview is published. How does that color your future dreams?

MDJ: I am always trying to make myself better, less broken, more intelligent, better read, and a better friend and lover. Having a child will not have any bearing on these constant attempts. However, it will be of greater consequence when I fail. Yet, when I do fail, I hope it will be a learning experience for our child in the sense that it is ok to fail, and that whatever was attempted was worth the try. I will be there when my children fall, to encourage them to try again. We live in an amazingly beautiful, vast place, and it is my job to show as much of this vastness as I can to my son or daughter, while helping them feel important and significant, which I don’t think many people feel. I am also trying to express myself through affirmative gestures, which are not about being “positive,” but rather stating who I am rather than who I am not.

BA: You have a strange relationship to politics — hero figures like Eleanor Roosevelt tend to be from the past — and suggestions that your work has political implications seem contrary to your stated intentions. But since you welcome, or at least include, utopian thinking in your project, can political problems and solutions be ignored?

MDJ: I think that politics perpetuates most of the awful things that happen in the world. I believe that this is a problem created through the specialization of the politician, one who can do nothing more than to be a politician. I want to see a time when engineers, scientists, philosophers, maybe even artists can be caretakers of the society we live in. You could also apply this general feeling of politics to how I feel about art. I am an artist, but art is just a safe place to embark on a general research project towards a better and more comprehensive understanding of the world I live in. Nothing can be ignored, each part is as important to the whole as any other part. Politics is an important part of our daily lives, and I can’t separate my political concerns from my work, and would never try. However, the best way I can help is to volunteer, and to use my skills in a practical sense. In trying to express myself in the affirmative, I believe that much of what I do is to describe a sort of utopia.

BA: In some interviews you have discussed your morbid thinking, the ideas of suicide and death that color your work. I personally don’t feel afraid of death and feel that wherever my life journey ends is fine, but I hate the idea of missing the next chapter in the book. I want to see what technology and culture can instigate in the ten years after my death. What are you afraid of missing?

MDJ: I think that in order to grow we need to kill ideas that we have of ourselves. We need to shed our skin periodically, like a snake shedding its skin to grow. I have talked about this in terms of suicide, and it is a recurring theme in the work. This is a reaction to living in a society that is syncopated by moments like our first steps, our first words, high school graduations, losing our virginity, etc. Our constant looking to the next step, or romanticizing the last step, creates a situation in which we are not living for the moment, and not paying attention to the little lessons we learn daily. I am not afraid of death. I am not afraid of missing anything. I am more afraid of being alive and wasting even a minute of this beautiful time. When I think about the great things that I have missed by not being alive, it is ridiculous to think of what I will miss in the future. The past lives in me, and in us. We will all be part of the future, so don’t worry Bill, you won’t miss a thing.