F for fair and BCAM for Broad Contemporary Art Museum

As I write this, LA galleries are already preparing for the Art Weekend in April, but two events have kicked off the beginning of the year: the Art LA fair and the BCAM opening.

First came the fair: Art LA showed a tight selection of about 60 top-quality galleries from the US and Europe (mainly from Germany and the UK). Although the fair was small — which is good — and sales figures were also small — which is bad — numerous professionals and non-exhibiting gallerists flocked to LA to check out the fair (maybe they’ll participate next year?) and to look for new artists, new collectors and new partnerships. Fueling the fair with LA’s power of attraction was part of fair director Tim Fleming’s formula, working with consultant and LA art dealer Daniel Hug — already Fleming’s partner during the golden days of the Art Chicago fair and now fully at work at Art Cologne 2009, as its new director.

Then the museum: BCAM, LACMA’s new building for contemporary art, subsidized for almost $60 million by collectors Eli and Edythe Broad, opened in February. During the month preceding the opening celebration (a week crowded with events that culminated in a Hollywood-like gala), the Los Angeles Times ran an almost daily series of stories, of which the most controversial examined Broad’s decision to provide LACMA with loans from his collections but not with a hoped-for donation; the most recent revealed that LACMA has purchased a new parcel of land just across from its campus.

BCAM marks the conclusion of “phase one” of a three-part plan for reconfiguring the LACMA complex. All of this work is in the hands of Renzo Piano, as per Broad’s wishes. Piano’s new building is a bright, travertine box with an exterior that reveals structural steel beams reminiscent of the Pompidou but here colored red. The interiors too show Piano’s typical signature, especially the high-ceilinged top floor’s perfect natural light filtering in from the roof.

BCAM has a solid container, but what is contained is arguable: the opening show, which will last one year, is a compilation of blue-chip works mostly coming from the Broad collection. The works are strong, but the show has no vision — it’s assertive and muscular. The ideas of a collector never unfold; instead it’s a survey of the art of the second half of the 20th century, legitimized by an institution in the manner of an art history textbook, except that many crucial chapters from the last 50 years of art history are inevitably missing.

In the outdoor plaza, the sun hits Chris Burden’s new installation comprised of 202 streetlamps; between this and Charles Ray’s life-size fire truck toy is Robert Irwin’s landscape work Palm Garden made of different species of palm trees.

Inside, one ideally follows a chronological path through a series of solo shows, starting from the Jasper Johns room, with the beautiful Two Flags from 1973, and a Robert Rauschenberg survey of samples from the main phases of his career. The Ellsworth Kelly room is perhaps the best: five large-scale paintings (from 1953 to 1972) are bathed in the gallery’s diaphanous light. Also notable are Cindy Sherman’s photo-filled room, Mike Kelley’s Day is Done (Gym Interior) and Jeff Koons’ majestic hall — which recalls the recent Koons gallery of works at François Pinault’s Palazzo Grassi in Venice.

There are outstanding works on view, but one wonders if a public museum like LACMA can rely mainly on the holdings of a single collector/patron. Some note that BCAM marks a milestone in the history of US museums, leading the way toward increasingly blurred relationships between public institutions and private collectors.

Ghosts of the City

Revered LA artist Michael Asher exhibited a stunning work at the Santa Monica Museum of Art, in which the idea of the void eventually resolves as a filled room. Asher’s name is inextricably associated with the ‘radical’ party of conceptual art known for institutional critique, and has influenced numerous LA artists in his role as a professor at CalArts since the late ’70s. An Asher show is a rarity nowadays, but Elsa Longhauser — the director of this kunsthalle-like museum with no collection but a strong program of exhibitions — convinced him to undertake this one, on which they worked for years. The show coincides with the museum’s 20th anniversary celebration, and it consists of a historical reconstruction of floor plans from 44 exhibitions over the past 10 years (since it moved to the current venue): aluminum wall studs delineate all the temporary walls constructed for these 44 shows (the studs only, without drywall) resulting in a traversable labyrinth both oppressive and playful. With the usual evanescence that characterizes his work, Asher evokes the phantoms of all those that animated the museum before him, turning the space of a solo show into a densely populated zone.

Curiously, at the current Whitney Biennial an artist in his mid-thirties, William Cordova, mirrored Asher’s approach: in a small room, he evoked a portion of a Frank Lloyd Wright house by erecting studs according to Wright’s floor plan.

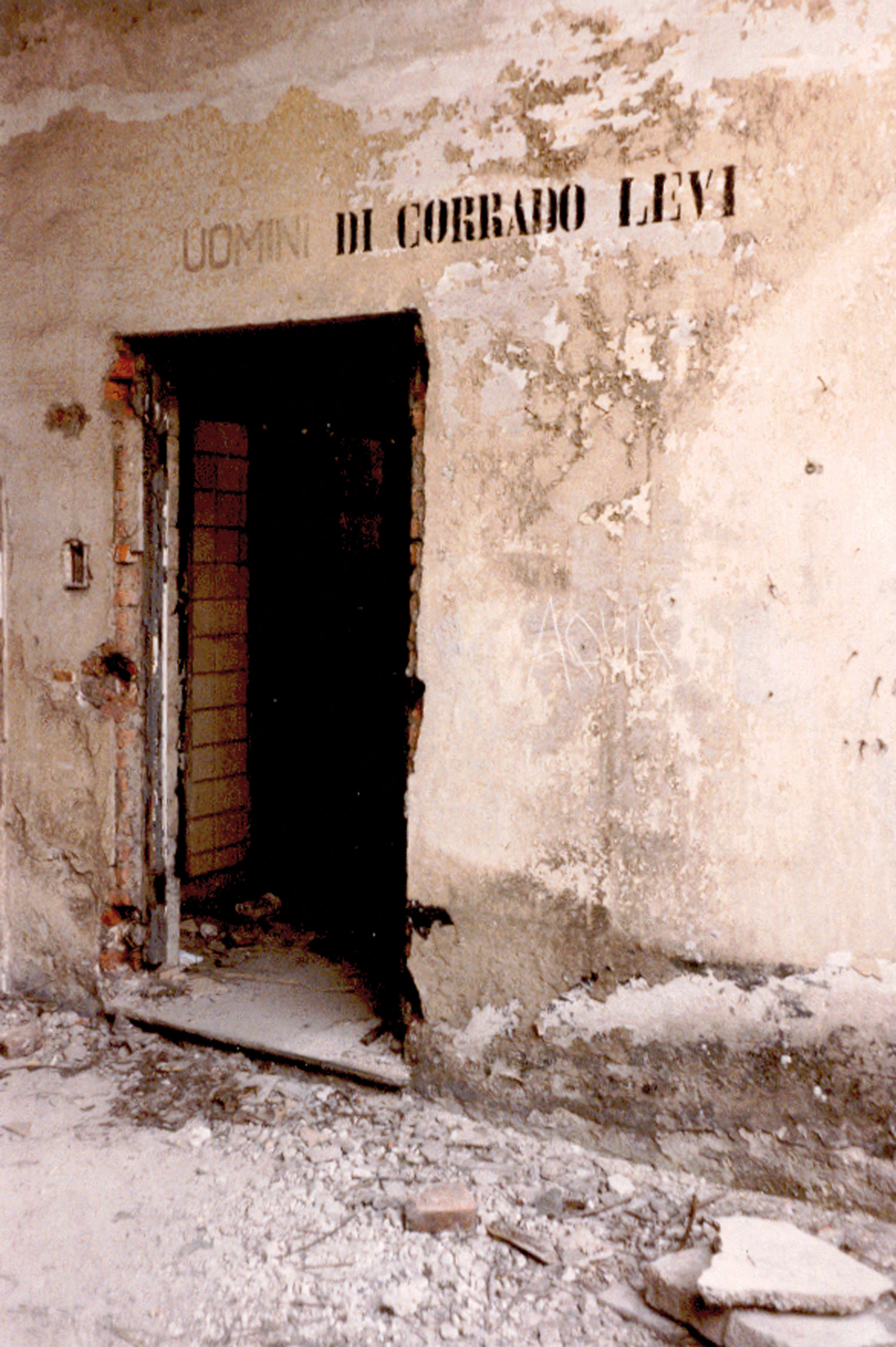

Another show conjures up ghosts: Andreas Hofer realized a “Phantom Gallery” in a temporary space that his gallery, Hauser & Wirth, has rented in Hollywood for this purpose. This is an empty shop or office-like space with a window onto the street, and the work consists of the empty space itself — its walls, ceiling and floor. But the emptiness is not void; at second glance the space reveals the genius loci in the form of traces on the walls, indicating the previous locations of furniture and paintings, and by extension the lives of earlier inhabitants that we cannot see but imagine.

These ghosts might suggest a Gregor Schneider-like experience, but while Schneider rooms are claustrophobic nightmares that look inward, Hofer’s intervention is more conceptual than extrasensory. Indeed, the project is completed by a sister “Phantom Gallery”: Hauser & Wirth opened the same show in their Zurich venue — on the same day and at the same hour — connecting the spaces via real-time streaming web cameras. The pieces — i.e., the spots on the walls — are for sale.

The City Lights

Honor Fraser — an ex top model of aristocratic Scottish origins and a former collaborator at Gagosian’s New York gallery — started her first gallery in Venice, in 2006. Recently she relocated to Culver City, in the same building as David Quadrini’s Angstrom Gallery. With the new location, she’s added some innovations to the gallery program, including new artists to her stable, beginning with Gardar Eide Einarsson (a Norwegian artist living in New York, currently showing at the Whitney Biennial too) who inaugurated the new space.

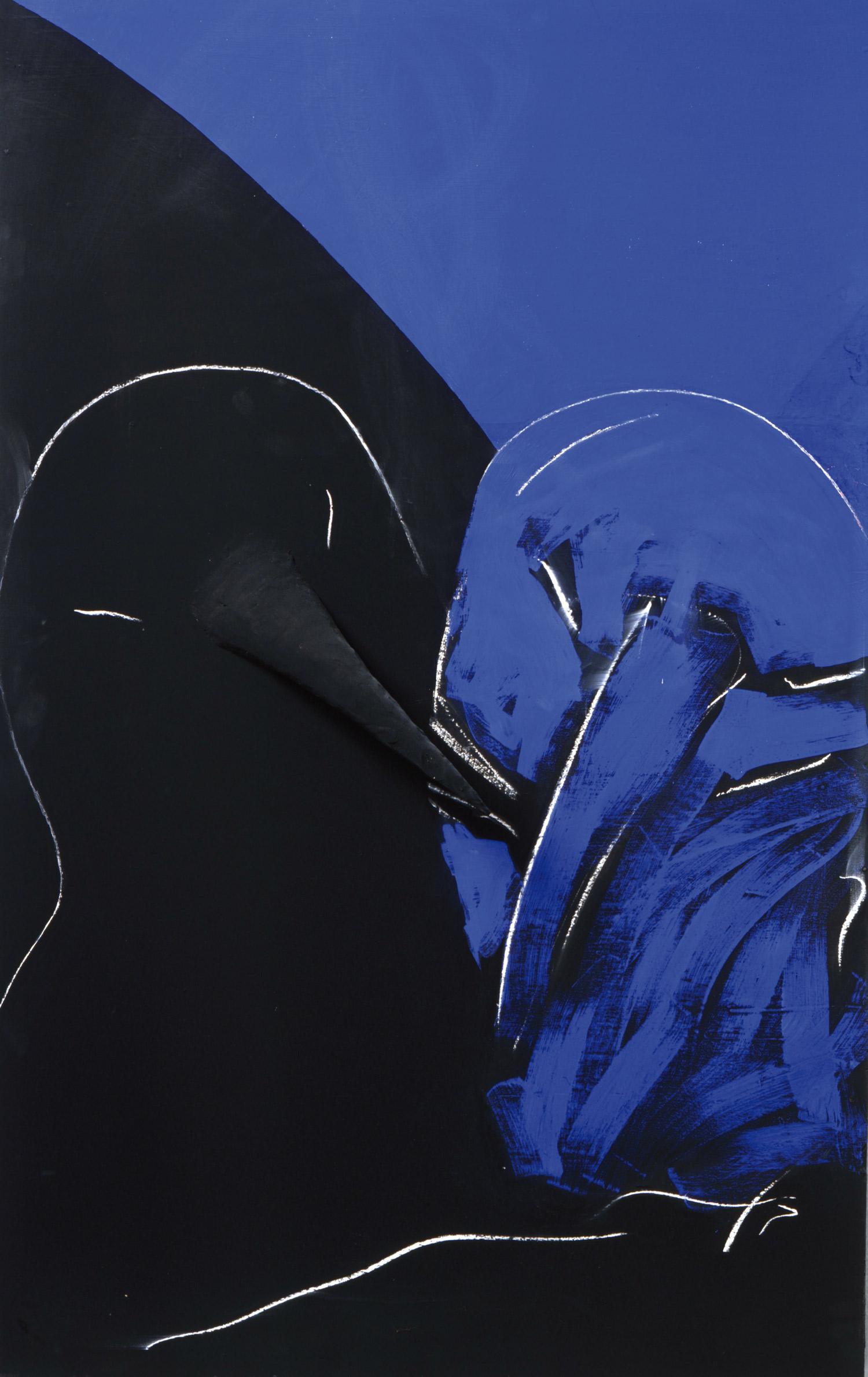

Appropriating the language and signs of street-graffiti, tags, handbills etc., Einarsson’s lexicon pervades his installations with a strong graphic quality. All My Friends Are Dead, the main piece in the exhibition, consists of a sequence of images — pictures of a policeman, sourced from a ’60s guidebook, who demonstrates how to use a riot baton — in the form of grainy black-and-white inkjet prints on plywood.

One of the most interesting works is a small photograph of a street in Berlin during the ’30s, which depicts Nazi Party and Communist Party flags hung overhead. Recalling the appropriationist works of Richard Prince and Sherrie Levine, Einarsson has merely reproduced the image and brought it into the gallery. In his works, the alteration of an image’s details or context — a technique that the Situationists would have called détournement — transposes its content into new semantic fields.

Another new gallery is active in the city: Michael Benevento worked in the art world for about 15 years — as a dealer, an art critic (one of the founders of The Journal of Art) and an ad representative. Now he runs a secondary market office in New York, and since early 2007 he has commuted to LA where his new gallery devoted to emerging artists is located on Sunset Boulevard. He works in the gap between the local and the international art scene, and brings to LA artists rarely shown here, such as New York artist Peter Coffin. During his show, the gallery space was infused with ever-changing colored lights and shadows, and three life-size black aluminum silhouettes of iconic sculptures: Rodin’s The Thinker, Max Ernst’s Capricorn and Sol LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cube. Throughout the show is a series of posters rhythmically spaced on the walls from the entrance to the end of the gallery. These feature rainbow-colored backgrounds as seen in rock concert posters from the streets of LA. Working with the LA printing company that produces them, Coffin produced a new version that eliminates all text but retains the ambience of the original.

Both works examine the canons of representation through the lens of art history and figuration. Figuration appears in the silhouettes but vanishes from the posters; history is in playful evidence in the sculptures but deleted from the posters, which in turn become abstract pictorial motifs.

“Globetrotters” is an exhibition of LA sculptors organized by Katie Brennan, the owner of Sister in Chinatown, in a space that she rented for the occasion just a few blocks from the gallery. The seven exhibiting artists — Katie Grinnan, Evan Holloway, Jason Meadows, Pentti Monkkonen, Amy Sarkisian, Eric Wesley and John Williams — were born in the late ’60s an early ’70s, and studied at UCLA and CalArts. Brennan recalls, “They were my heroes when I started to work in the art field as a gallery assistant. LA is known for sculpture because of these artists.” For each of them she selected one significant early work and one or more recent works. For instance, Jason Meadows has two sculptures, one from 2006 and the other from 1999. The latter, titled Trailer, caches the archetypal elements that then became his signature: bricolaged shapes and the idea of primitive, Dadaist machines; whereas Eric Wesley’s two small assemblages of cowboys and stagecoach toys are chaotic tangles cast in bronze. The first group was made in 2002 and the second is its more recent remix; the result is two similar but not identical arrangements, lightly parodying the idea of authorship.

All the sculptures in the exhibition have a time-based quality that, as a whole, cast a valuable perspective on LA’s sensibility: they are performative, humorous and fetishistic approaches to assemblage that convey an extravagant sense of the playful and uncanny.