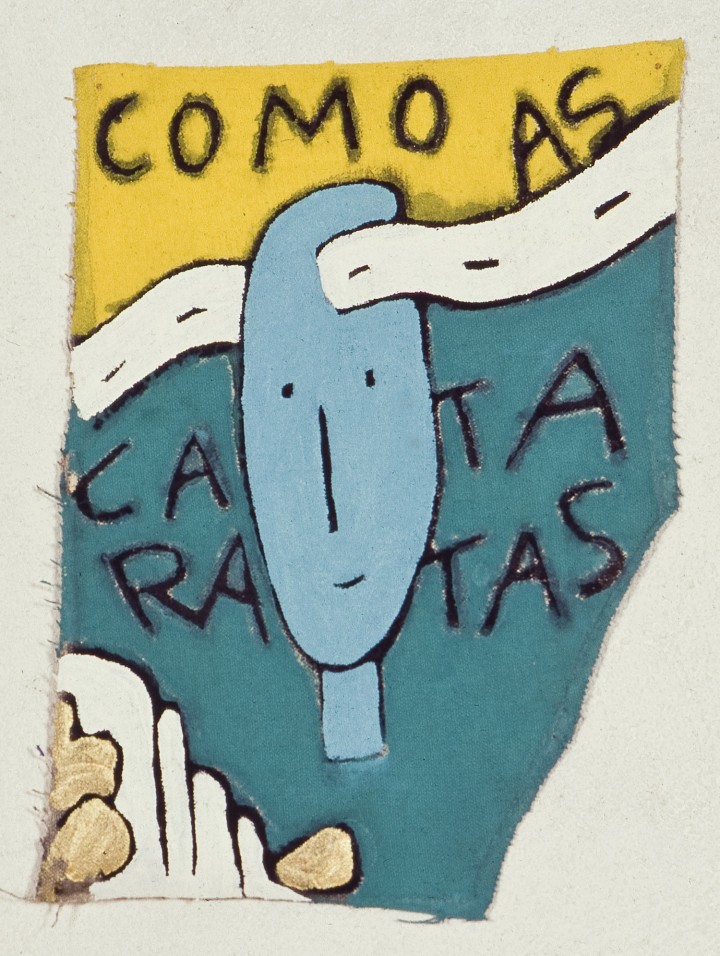

In 1984, when he took part in the group show “Como vai você, geração ’80?” [How are you doing, ’80s generation?] at the Parque Lage Arts School,along with several artists of the same generation, Leonilson was a twenty-seven-year-old painter who, like many of the other participants — Luiz Zerbini, Leda Catunda, Beatriz Milhazes, Daniel Senise and Nuno Ramos, among others — enjoyed experimenting and innovating, showing mainly his unstretched canvases fixed directly to the wall through eyelets. At this time his style was already quite recognizable, but it still bore the visual influences of the international movements that marked the return of painting earlier that decade, especially the Italian Transavanguardia, with which he had firsthand contact during his long trips to Europe in the previous years. Over the following decade, and mostly at the end of his life, from 1990 to 1993, his language would go through a deep transformation, which somehow places Leonilson on a common trajectory with other artists like Milhazes or Ramos — to mention only a few of the most acknowledged names these days. But both the path followed by his work as well as the dramatic course of his personal life make him a unique case in the Brazilian context.

Homosexual, in 1990 he learned he was HIV positive, and after a period in which his work became a poetic and sublime rendering of the progress of the disease and the transformations it brought, he died of it in 1993 at only thirty-five. Becoming less figurative and more literary, almost invaded by a void that turned sparse elements into isolated and solitary ones, his late works have been interpreted by critics as a reflection of his personal Calvary, despite the fact that many of these iconic traits actually showed up before the disease. Although arguable, this absorption remains perfectly cohesive in the case of Leonilson, an artist who, since the beginning of his career, struggled to inextricably link personal life and artistic production, to create a body of work that has already been defined as “almost exclusively autobiographical” [Lisette Lagnado, “O pescador de palavras,” in São tantas as verdades, SESI, São Paulo, 1996, p. 28]. In an interview made a few months before his death, the artist himself, when comparing the way he worked to the poetry of Constantin Cavafy, stated: “He used to go to a café in Alexandria and kept talking about, describing the guys he saw there. In this drawing I wrote ‘good news.’ I had a date with my boyfriend at 5:00 pm, and it wasn’t until 10:30 pm that he called to say: ‘Leo, I might be a little late…’ Meanwhile, I kept on drawing. To make it simple, it is like the work of a reporter.” [Lisette Lagnado, “A dimensão da fala,” interview with the artist, in São tantas as verdades, op cit., p. 113.]

José Leonilson Bezerra Dias was born in 1957 in Fortaleza, state capital of Ceará, in northeastern Brazil. Despite having moved to São Paulo with his family while still a child, his work would be marked by the visual elements of his birth region, such as the simple and direct iconography of Cordel literature — a popular literary genre in the northeastern region, consisting of simple stories inspired by folk legends, day-to-day episodes or historical events, often rhymed and illustrated with engravings — as well as religious symbols that would become recurrent in the paintings, drawings and embroideries of his late work. His choice of embroidery as a preferred technique also leads back to his childhood: his father was a fabric trader, and his mother used to spend hours sewing and embroidering. On the other hand, Leonilson himself approached his embroideries in the tradition of naïve or outsider art. He was notably influenced by Arthur Bispo do Rosário — a former mariner and boxer who produced a unique bodyof work over a few decades, after being diagnosed with paranoid-schizophrenia and admitted to the Colônia Juliano Moreira psychiatric hospital — as well as other inspirations, such as the North American religious movement of the Shakers, or the fabrics of the Pre-Columbian era, rotted by time and inclement weather. The ability to integrate countless references, thus taking ownership of the features that directly relate to his extremely personal poetics, is a distinctive trait of Leonilson. From this diversified and profoundly refined stock emerges a work characterized, above all, by the capacity to establish immediate empathy with the observer, to whom it seems to speak in a direct and stripped-down manner, whether through the apparently unassuming traits of the characters or the use of familiar and warm materials. This is especially true of the embroideries produced in his last years, which were created in a small format and lacked the “violence” of his juvenile paintings. In spite of having a less violent tone, these works have an extraordinary force. With aplomb and self-consciousness, they nonetheless maintain traditionally feminine techniques. Aware of this manifest paradox, and tracing an analogy between his own work and that of some Brazilian female artists he admired, like Lygia Clark and Leda Catunda, Leonilson stated: “When I see Lygia Clark’s work, I feel this power of women. And I think of myself. I am now weaker, sometimes I get stronger, but I keep thinking that I’m doing these delicate objects, small embroideries. I notice there is a pretty big parallel. Back in the days we used to do big paintings, I felt like we had to use violence, strength, but now I feel like all that is just so stupid. One has to have been through all that to make a small piece of cloth like this one.” [Lisette Lagnado, “A dimensão da fala,” interview with the artist, in São tantas as verdades, op. cit., p. 89.]

Although the general tone of his works gets more peaceful and delicate over the years, it is important to note that they also acquire an ever-increasing literary and poetic aspect. Influenced by poets and writers, as we have seen, he started to include more and more verses, his own or by other writers. Yet, seemingly banal words and sentences have come to particularly and unmistakably characterize his work. In this sense, it is worth noting how these words simultaneously become more present and benefit from tremendous freedom. That is to say, they gain an inwardly poetic status; exempt of the conventions ruling the prose, the words of Leonilson are clearly “his,” and that is how the presence of misspellings, as well as grammatical and syntactic imperfections, must be regarded. Far from being a product of ignorance, negligence or improvisation, these anacolutha allow the artist to take possession of the word in an intrinsically intimate and personal fashion. Scathing and concise word descriptions, such as Ninguém, Mentiroso [Nobody, Liar, 1992] or O Perigoso [The Dangerous One, 1992], become privileged instruments for building a sort of imaginary, non-figurative self-portrait. In other words, the human figure — which must always be considered representative or at least allusive to the artist himself — becomes almost absent in his late works (the exception to the progressive fading of the human figure in Leonilson’s work are the weekly drawings for the “Talk of the town” column,written by journalist Barbara Gancia at the newspaper Folha de São Paulo, between March 9, 1991 and May 14, 1993), ceasing to be intimately tied to the personal life of its author. In a moment when the artist no longer recognizes himself in his own body, transformed and mortified by the disease, the task of representing it is assigned to words, numbers and other recurring personal information from this phase. In this sense, the work El Puerto (1992) ranks among the most explicit. A piece of cloth cut from a shirt of his has the following embroidered inscription: “Leo, 35, 60, 179,” in reference to the artist’s name, age, weight and height, respectively. The cloth covers a small mirror, which throws open the mechanism of replacing the real image for physical data, but also recalls both the coming and ineluctable absence of the artist, as well as, in a broader sense, the inevitable character of death for anyone looking at oneself in the mirror. The work then turns into an almost conventional memento mori due to its crystal-clear affect.

Leonilson’s last works were produced for a major installation that occupied the Morumbi Chapel in São Paulo in 1993 — a project he was not able to see finished. Photographic records show familiar, household objects, like chairs and embroidered shirts, silently occupying the space. Even though they are predominantly white in color, the feeling that remains is that of grief and loss. Educated in religious schools, and impressed at a very early age by the visual strength of catholic symbols — fisherman, pearls, lilies, the rosary, fish, sheep, candles, the sacred heart, all of which recur throughout his trajectory — here the artist reaches the apex of his relationship with the sacred. “I’m not catholic. I don’t go to the church. But I pray every morning asking to be taken care of. […] I keep doing these works as prayers, just as the Hindis do their embroideries. It is like a religion that provides symbols. Once you believe them, you can get somewhere.” [Lisette Lagnado, “A dimensão da fala,” interview with the artist, in São tantas as verdades, op. cit., pp. 118–119.] At first reading, a statement like this one might seem to reinforce the ambiguity that the artist himself considered to be the cardinal feature of his work. But ultimately it supports the certainty that Leonilson, with an innate and instinctive capacity to progress by means of successive deviations, and without ever following a straight or predictable line, indeed “got” somewhere. That is, he got to produce a body of work that still today, more than twenty years after his death, and even after having been subject to numerous retrospectives, continues to surprise and thrill.