Mike Kelley: Tulsa was the first photographic work I ever saw that realistically depicted the drug scene. It shocked me because, at that time, that was not something you saw in the art world. How did you come to make those photographs?

Larry Clark: I’ve been a photographer since I was a teenager. My mother was a baby photographer, going door to door. I always had my Rolleiflex and strobe with me because I was working for my parents. I never thought about photography in other terms, as art or anything. But then I went to a commercial photography school which happened to be in an art school. So I was exposed to kids who were doing art and to a lot of the documentary photography from the old Life magazine of the ’50s when they were doing those great photo essays. Eugene Smith had quit Life because they wouldn’t give him enough time to do the assignments. He was always writing these diatribes about the ‘truth,’ and how he wanted to tell the truth. One day I snapped, hey, you know, I know a story that no one’s ever told, never seen, and I’ve lived it. It’s my own story and my friends’ story. I would go back to Oklahoma and start photographing my friends. That’s when it snapped — I wanted to be a storyteller. Which I hate even to admit to now, because I hate photojournalism so badly.

MK: Was there some kind of heroic aspect to this? I’m thinking of beat literature where a subculture is pictured in really exalted terms. Or Robert Frank’s photographs, for instance, which have a very romantic quality to them. Were you familiar with this stuff? I’m asking because your work doesn’t have a photojournalistic look to it. The situations, positions, and places in Tulsa look too real to be posed yet there is, at the same time, a strange, ‘fictive’ quality about the work.

LC: I wasn’t familiar with those people at that time. It’s interesting about the fictive quality… but you know it’s real, it’s documentary. I grew up in the ’50s with all those great B-movies, “film noir” they call it now. Double features, triple features every Saturday… with all the dark shadows in them. In the beginning, I was just trying to make photographs. Someone would come in and I’d see a light and shadow and recognize things that were dramatic. I was trained as a portrait photographer. And you’ve got to make people look good or you don’t get your $10.95. Many photographers and photojournalists are great at grabbing the picture, being quick and focused and framing the composition, but they don’t care what the people look like. I did.

MK: It’s true, in Tulsa people generally look good. Like the guy on the bed with the gun, or even the pregnant woman with the needle in her arm. Perhaps that’s part of why the work seems fictive to me. They’re very classical pictures. In fact, the photos might be even more shocking because the scenes depicted are not made grotesque or seedy like they normally are in photojournalism dealing with drug culture.

LC: The shot of Billy on the bed with a gun, I always looked at that as like a baby picture. If you looked at some of the baby pictures my mother or I took, it could have been that pose. I didn’t get it at first, but I knew it was great. It was a natural picture. With the white sheet in the background, it could be a studio picture. I was able to get that quality when it was actually happening, that quality of looking set up.

MK: Tulsa really is very cinematic. Even though there is no coherent narrative it seems as if there is one. I think that feeling is accentuated by the fact that there are a few sequential photographs, and some prints of film strips.

LC: There was a trick there in the Tulsa book that I didn’t even realize until later that makes it look cinematic. No one looks in the camera. If you do a whole book where no one looks at the camera it’s like a movie. I had to leave out a lot of good pictures because they didn’t fit the flow.

MK: When did Tulsa come out? I know you did some of the photographs when you were quite young and then went back after you’d gone to school and shot more.

LC: It came out right after I finished it in 1971. The first section is 1963, the middle section is 1968, and then the last section is 1971. About half of the book is 1971. I went to Tulsa and did all those pictures in a matter of months. I knew every aspect of the life and knew what was missing from the book. I went back and was almost… waiting for those photographs to happen. I didn’t know how they would happen but I knew I would be ready.

MK: Even though you subtitled Teenage Lust an ‘autobiography’ it seems more removed than Tulsa. There are photographs of you involved in the action, and in Tulsa that wasn’t the case, but it has the quality of operating in memory.

LC: Teenage Lust is about going back and photographing the past. I had known this next generation since they were little kids. When the Tulsa book came out they looked up to us and to me as a kind of hero. I just told them what I wanted to do and they let me come back with them. It was like living out a fantasy to go back and relive and photograph your past.

MK: It’s interesting to me that in one series of photographs you show yourself interacting with the teens. There’s an obvious age difference yet it seems as if the viewer is asked to accept that there is no difference.

LC: I even captioned the picture where we’re naked in the waterfall, “Self-Portrait with Teenagers.” A lot of those pictures are about me trying to be a teenager, to validate that time for me, which I felt I didn’t have. I was always late, and I missed that time and there’s always that desire to go back. I always wanted to be the people I photographed and I think using these people is like this perfect childhood. I always thought that Tulsa didn’t give me the satisfaction it should have because I was twenty-eight when it came out and I thought I should have done it when I was seventeen.

MK: What do you mean you missed being a teenager? Even though Tulsa didn’t come out when you were a teenager you started the project soon after. And it was your scene you were photographing.

LC: Even in Tulsa when I was photographing my friends, I wanted to be my friends — anybody but myself. I was really just a skinny little kid who picked this identity and these people to hang out with. I’m a tag-along guy who’s fifteen and looks twelve. I didn’t reach puberty until I was almost sixteen. At this point my father had just come back; he came back when I was twelve, in sixth grade. He was a traveling salesman on the road. My mother always said, “Everybody likes your father, he is such a nice guy.” Every fucking day of my life she said “how much everybody likes your father.” And, of course, I loved my father; I didn’t start puberty and he looks at me and says, “What did I do to deserve such a scrawny little kid?” and quit talking to me. My parents sent me to get some vitamin B-12 shots. No one said it was O.K. I remember sitting in the bathroom when I was fifteen and looking down at myself and saying if I don’t get some hair on my dick by next summer I’m going to kill myself.

So I started this secret life. My first secret life was I hadn’t started puberty yet. Then I started hanging out with these drug guys and it was a secret lifestyle. Drugs weren’t mentioned back then. So it was just layers and layers of secret lives. When I was almost sixteen and I started going through puberty, that’s when I started shooting speed.

MK: So puberty and drugs were like a mixed rite of passage?

LC: Right. When I’m sixteen I’m like thirteen really.

MK: So this impulse to go back is an impulse toward normalcy?

LC: Normalcy, right. I was a freak, a secret freak. That was always a fantasy of mine, to go back to high school and do it again. To do it right. There’s also this sexual fantasy that I have, and it’s to be a fourteen year old kid, right? Going through puberty, you know, at fourteen, normally… you see I say ‘normally.’ You see I still think there’s something wrong with me. But to be fourteen years old, and I even know how I look. I know how much hair I have on my dick and I have a sister who’s having a slumber party and she’s got five or six seventeen-year-old girls. I’m the younger brother. And they get me to take my clothes off and I dance around for them and they’re playing with me and I get to fuck them and they sit on my face and I’m eating their pussy and…

MK: Do you think your work is erotic?

LC: I think all the work is erotic somewhat. I like my work to look sexy and it does look sexy. But do you mean for me or for the viewer?

MK: Well, for either. When you make these works you are obviously aware that other people are going to look at them.

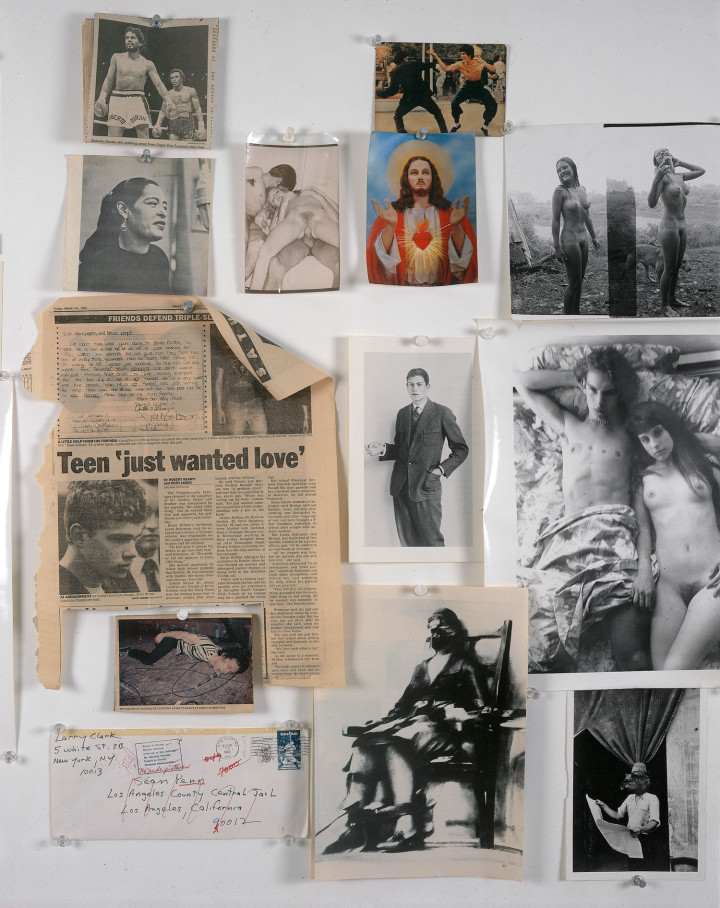

LC: When I did the collages, for example, the purpose was not the viewer at all. My most successful work, like Tulsa, I felt had been done on a purely emotional basis. I think it was Andy Grundberg of the New York Times that wrote that my work was psychotherapeutic. I said, somebody finally got it. I always felt that was going on.

MK: A lot of people see your work as homoerotic, especially the more recent work like the collages and the large-scale sequential photos of teenage boys. There are certain gay artists showing now whose work on the surface recalls yours.

LC: They just can’t get past the fact that it’s teenage boys. Someone I know once showed Allen Ginsberg Teenage Lust. Allen looked at the pictures and asked “Is he gay?” and my friend said “No”; Allen said “Wanna bet?” There is that aspect, if you have fifteen year old kids in your pictures with hard-ons, people are going to think that. But what can I do about that? My wish would be to go back and be that age and be one of those normal kids.

MK: How did you shift from doing the photo books into doing collages?

LC: I came upon the collages by way of doing photographic triptychs. I wanted to get away from the books. I was seeing everything as a double page spread. I was doing a project called Children of Alcoholics, photographing a kid who was having trouble with drugs and alcohol and who was living in a family that was drugs and alcohol. I had gone out and photographed this scene and it came down to three photographs that I liked out of all of them. They told the story. So I made some triptychs. This led to the first collage, where I took a picture from a magazine and put it with one of my photographs. It was a picture of Matt Dillon when he was about fifteen years old with his shirt off. Then the collages just kind of grew. I started thinking about all this stuff in the newspapers about teenagers killing their parents. There was one about a kid who slaughtered his parents; he slit their throats and hit them on the head with bar bells. What was interesting to me was that he was naked so he wouldn’t get blood on his clothes. And the first thing I wondered when I read the story was if the kid had an erection when he was killing them. I said, God, what a fucking image!

MK: I remember the mental image of Lizzie Borden killing her parents used to get me hot. It was the same thing, she killed them naked so she wouldn’t get blood on her clothes.

LC: And then there were all these stories about autoerotic asphyxiation. There was an article in the New York Times that I used in a collage about a rash of suicides on Long Island, about five in a few months. Everyone wanted to know why all these kids in this small community were killing themselves. It turned out they were jerking off while they were hanging themselves. The parents would clean up the scene and it would be called a suicide… it was better a suicide than be embarrassed by their kid jerking off while strangling himself and dying.

I was thinking about things you couldn’t photograph. How are you going to document a kid killing his parents? How are you going to be there when a kid dies from autoerotic asphyxiation? The collages were a way for me to deal with that problem, to tell the story in another way.

I did one collage about the New Hampshire murder case where a twenty-two-year-old teacher came into this high school to teach drugs and alcohol and she seduced a fifteen year old boy who was a virgin and got him to kill her husband. It’s a mix of pictures of sexy teenage actors from teen magazines, photographs that I shot for it, and the article about her that reproduces Polaroids she took and gave to him. This is the only one I ever titled — The Perfect Childhood. Because that is the perfect childhood. Wouldn’t you like to be fucking the beautiful twenty-two-year-old teacher when you were fifteen? This kid’s got everything. And then the Hollywood-perfect childhood goes bad: the kid’s got twenty-eight years and she’s got life without parole.

I’d been seeing all these newspaper stories about kids murdering their parents but the kids didn’t look right. They always looked twisted or older than seventeen, but this kid looked perfect. He’s got his Motley Crue T-shirt, the jean jacket, the long hair, and just a wisp of a moustache.

MK: Didn’t you do some set-up photographs of boys simulating autoerotic asphyxiation and other things?

LC: I tried to set up some photographs like I see in the newspapers. I couldn’t, they were ridiculous-looking. I got one kid hanging like a suicide. I used it in a collage. I was trying to get to the autoerotic thing but I could only get him to do so much.

MK: How do you find these teens and what’s your interaction with them? Do you hire them?

LC: I’ve done this about three times — I’ve gotten kids to model for me and I pay them. It’s just straight professional modeling. I just brought them into the studio and photographed for five or six hours, just click, click, click — talking, eating a sandwich, smoking a cigarette, or trying to set something up like pretending they were cutting their wrists. I saw all these pictures and tried to pick out one good picture and I said, what if I just print them all? What if I take all these pictures and just cover the walls of a room with them? Or do a book and have them all, page after page with no writing. Just one kid, fifty pictures… two hundred and fifty pictures.

I had made some twenty-four-by-twentys for a collage. They really looked good big. My other work didn’t look good big. Like the Tulsa photographs, if you make them big it changes it, it’s like you’re exploiting it.

Now I just photograph the kids over and over. Everything is stripped away. I don’t need the drug scene, I don’t have to have them hanging themselves, I don’t have to have the teenage lust life, I don’t have to have my whole forty-eight years, all I have to have is just the normal kid sitting in the chair. The photos are getting looser and freer. I don’t have to find this idolized picture of the kid in ten rolls of film. Every shot is important because it’s not about taking a photograph anymore, it’s about me photographing the kid.

MK: That reminds me of action painting. You don’t think about the image as much as you think about the activity of production.

LC: The idea is to put all these fucking teenage boys in one place and just finish it there. Just put the whole obsession with going back in one book and maybe it will be finished, maybe I can do something else.

Now I’m thinking I’m right on time, wherever I am today I should be and all of a sudden I don’t feel that I’m late anymore, man, it takes a lot of pressure off your life.