Kirstine Roepstorff’s 2007-2008 series “It’s not the eye of the needle that changed – The Time / The Self / The Frame” references a proverbial theme. According to the Bible, Jesus explained to a young man that it was less probable for a rich man to enter heaven than for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle. The title expresses notions of process; suddenly, questions of ethical aspirations, personal development and one’s surroundings come into play, as if to say that it doesn’t matter who or what you blame (your age, your weak ego or the negative influence of your surroundings) — you’ll never get through that eye of the needle, simply because you’re too big! This is more than a reminder of the responsibilities that come with ownership and wealth. As in many works by Kirstine Roepstorff, it is a meditation on ethics and morality.

Who Decides, Who Decides is the title of a book the artist produced in 2004, reiterating the theme of power distribution that keeps reappearing in her works, in what seems to be an effort to put the powers at play into perspective. In this sense, her work is just as much an expression of political commitment — albeit filtered into an individualized aesthetic practice. In large-scale collages that weave images ranging from the obscure to the everyday into multi-linear structures of crystalline complexity, the artist doesn’t shy away from questions that appear banal and redundant — but only until one dares to think of possible answers.

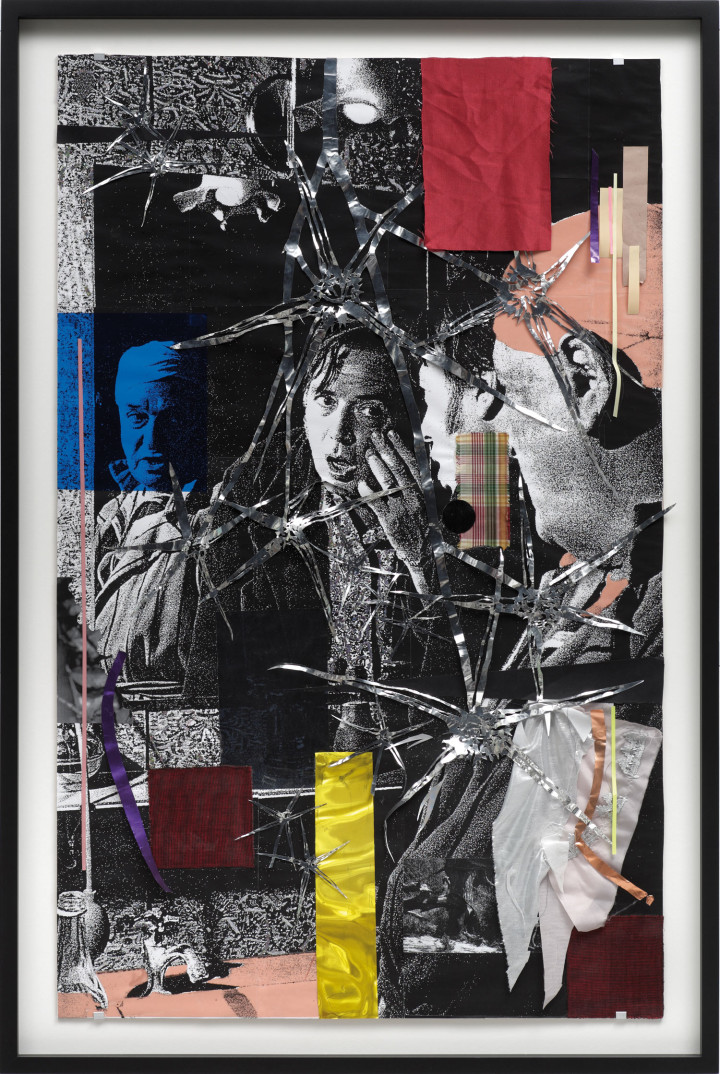

Her approach to collage can be seen as an experimental philosophical strategy. At the heart of it is the cutting out of images, with the resulting positive and negative spaces carrying traces of the other. It’s from here that the artist has come up with her own slogan: “Everything matters, even if it doesn’t seem to.” Pushing collage into wall-covering tableaux and expansive series with growing formal and narrative complexity, the artist builds drama on the wide scope of existing visual media representations. She incorporates images from the news as easily as historic material and advertising imagery, “appropriarranging” them in the process of photocopying, scaling, cropping, composing and editing the final works.

“I’m exploiting the already given reality, yet knowing it’s just a construction. And I let the images talk to each other in order to investigate the lines I am interested in.” Composing the works using different papers, but also drawing on other materials such as fabric, felt, leather and glittery foil, gives the final work a decisively haptic sense, adding physicality and thereby a sense of reality and identity, while contributing to a sometimes kaleidoscopic and visually overwhelming appearance.

Yet, as visually or semantically overwhelming as her work might be perceived at first glance, one takes the time to look at these works. It is easy to discover recurring allegorical characterizations of specific world principles that invoke the work of Hannah Höch, the Dada-founding figure of collage, as well as painter-philosophers such as A.R. Penck. For example, there is “Balance,” often portrayed by people juggling, in works like If balance stops and asks why, balance will die (2006); the scarily detached principle of “Happenstance”; or other players such as the “Moment Man,” the constant decline of “The Eel of Unfortune” and “The Dog Called Loss,” a painful creature of the past and lost memories. Not all her characters are as figuratively evocative. There are also the “Pears” — fruits of passivity that continuously grow into increasing turds of pure dead weight — or the always mysterious and shape-shifting “In-betweens.”

With these and similar allegorizations, Roepstorff manages to render topics of desire, adoration, beauty, success, power, social and economic relations from various perspectives and with relentless curiosity, exploring the cracks in the façade of our civilization, extrapolating her findings in her fabrications that never allow the viewer to forget that these too are products of this society.

This strategy was taken to a different level in her spectacular project Stille Theater [Quiet Theater] (2008), a work that is surprisingly talkative. Two (invisible) meta-characters, “Image” and “Space,” engage in a psychologically charged dialogue, aided by a moving display structure as a kind of theatrum mundi machine, vaguely reminiscent of the tree of knowledge. A whole league of the artists’ allegoric characters conjures up and informs the positions of “Image,” while “Space” argues from the point of view of social texture. The play liberates the allegorical characters of the collages and takes them into a realm of negotiation with reality, a cosmos of (sometimes rather unlikely) possibilities.

The project was never as romantic or melancholic as it might sound. By focusing on the limitations of perception, the artist constructed a paradox in her formula, emphasizing the subjectivity of personal experiences. By reflecting the problem of seeing the world as a whole when perception is intrinsically fragmented, this work — with references to and traces of global and personal history, both conscious and subconscious — wove a web of promises, memories, dreams and visions entangled with notions of the self as a (more or less) homogenous entity.

Maybe this aspect became most apparent in the artist’s recent enterprise, her group compilation/exhibitionc“Scorpio’scGarden” (2009) at the Temporäre Kunsthalle in Berlin. Realized at the breakneck speed of only two months, the show and accompanying ambitious performance program involved just short of forty Berlin-based artists, ranging from internationally established artists like Elmgreen & Dragset, Isa Genzken and Monica Bonvicini to emerging contenders such as Anna-Kavata Mbiti, Kerstin Cmelka and Fiona James. Instead of incorporating the individual works into her own narrative fabric, the generosity of Roepstorff’s artistic approach showed. Activating the vast space was an impressive curved ramp that was accessible to viewers and provided them with the illusion of an overview — while also serving as a somewhat megalomaniacal and weirdly instable plinth for the towering and slightly menacing black sculptures of Julian Göthe, the jingle-jangle paper column of Jason Dodge, Enrico David’s brooding Bulbuous Marauder (2008), Karl Holmqvist’s smart and sleazy linguistic sculptures and Amelie von Wulffen’s painted sofas. It also simultaneously embraced and undermined the theatricality of the Kunsthalle’s sheer volume. By structuring it with semi-transparent hanging blinds, she allowed the individual pieces and performances to become characters with their own agenda, without any strategic turn of legitimization by a governing principle other than the idea of a garden inhabited by competing ideas and visual strategies.

Apparently Kirstine Roepstorff saw no need to drag camels through eyes of needles. So there were no needles, nor even camels — but many open eyes, taking it in, and continuously changing and exchanging their views.