On August 15, 1971, on the day of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, Richard Nixon untied the US dollar from the gold standard. Being a good Christian, in God he trusted; and I wonder whether the decision to dematerialize the world’s currency on the day of the dematerialization of the Virgin’s holy body from earth to heaven was a deliberate one. What makes this coincidence even more interesting is that at this very same time the grounds were laid for a third case of dematerialization to occur, this time within the realm of architecture. It was mostly due to Nixon’s economic measures, in fact, that the “wall,” arguably the discipline’s enduring primordial element, was transposed to isotropic spheres and thus suddenly invested with quasi-divine powers reaching far beyond its materiality.

The revocation of the direct convertibility of the US dollar to gold was intended to untether value from any material equivalent. This transformed the nature of the dollar and, consequently, all currencies exchanged on the market, making them fluctuate solely according to each other as reference, allowing money to exist in relation to itself, groundless and immaterial. Curiously, even though the effects of this maneuver registered early on in the built environment, a dispersed movement of so-called radical architects and designers was at the same time envisioning a liberated society by way of the complete dissolution of architecture through a progressive sublimation from solid to gas. Superstudio’s Continuous Monument (1969); Hans Hollein’s Mobile Office (1969); Archigram’s Plug-in City (1964); the pneumatic experiments of Ant Farm, Quasar Kahn and the like; Reyner Banham and François Dallegret’s “A Home is Not a House” (1965)with nuanced differences, these all emerged to counter “traditional bourgeois values such as permanence, material assets, and solidity” [www.design-museum.de/en/collection/100-masterpieces/detailseiten/blow-de-pas-durbino-lomazziscolari.html] with new modes of inhabitation based on transience, flexibility and the kind of cornerless epidermo-platonic techno-chic aesthetic that makes them popular still. Like Nixon, they too agreed that society was to be liberated by the power of electronic systems and communication technologies, and that the key to this condition was a shared global infrastructure adapted to the exchange of all things.

But just as Nixon revoked the gold standard — meanwhile Steve Jobs was being introduced to Steve Wozniak and MoMA was preparing the seminal exhibition “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape” — a yet-to-graduate Rem Koolhaas embarked on a study trip to Berlin with the peculiar objective of architecturally documenting the GDR-built barrier. During this trip, Koolhaas reframed the nature of walls as devices of division, verifying the Eastern Bloc’s assertion that the wall was actually built to protect the “will of people” in building a socialist state. Noticing that the “free” side of the city was in truth the enclosed one, Koolhaas witnessed the power of the wall, which had, by itself, through the most archaic and crude architectural intervention, reconfigured the entire city and become a symbolic image for the state of the world. The effects of the Berlin Wall reached, in fact, far beyond its mere architectural presence, while the scale and scope of such ripples rendered the wall immaterial by comparison. Consequently, the Wall, speaking for all walls and architecture itself, was less about the concrete than the void, less about its thin edge than the real differences it actively produced.

The implications of Koolhaas’s argument reinforced architecture’s ties with production in the largest and most abstract sense. It showed that regardless what was divided, the division of a thing inevitably produced two things that could be weighed against each other by opposition. It was then evident that technologies of separation — whether walls, membranes or barriers — instrumentalized division to produce more difference; subsequently, they proved how separation was essential to the production of new meanings and values by giving reasons to communicate and exchange. Framed in this way, the immateriality of electronic systems based on the translation of all things into bits and digits was certainly less about emancipation than production.

In this light, Koolhaas’s early work is much closer to that of his techno-hippy and liberal contemporaries than he would like to admit. In both instances, the “immaterial” digital system was envisioned in opposition to the material limitations of architecture. His work on the Berlin Wall concluded that the physicality of architecture was powerless against abstract and immaterial systems. When he returned from Berlin, he declared: “For me, it was a first demonstration of the capacity of the void — of nothingness — to ‘function’ with more efficiency, subtlety, and flexibility than any object you could imagine in its place. It was a warning that — in the built environment — absence would always win in a contest with presence.” [Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, SMLXL, The Moncelli Press, New York, 1995, p. 228] Like Marx had understood a century before, the melting of all things solid into air was a matter of realizing the promise of capitalist production, thus making it more real, more functional, more adaptable and more efficient. As the Virgin Mary left her earthly incarnation for the holy heavens, capitalism consecrated the global stock market as the holy referent. From then on, monetary, aesthetic, cultural and moral values started feeling less like this –___–”””—__—-”””—____— and more like this *%&ª¶§^)&^•º∞(^$*^€¢∞¶∞£%(&^)(*&.

This patchy genealogy shows that walls, boundaries and membranes, being some of the most rudimentary types of interfaces, can be considered at once a paradigm of separation, of production and of communication. Their parasitic presence in the world is the fuel that keeps the machine productive. It also shows that an immaterial network of exchange was imagined simultaneously throughout the liberal spectrum, whether in aesthetics, politics or science. There was a general conviction that the only way out of the dead end of modernist politics was to divest materiality by overlaying immaterial systems of division onto the world. The shared ambition was to unleash the production of values, whether monetary or symbolic, which were believed to guarantee that liberty would become other. Divided and connected, plural and unique, immaterial and material, abstract and real: the contradictions of postmodernity might have been much more consciously constructed than it is usually believed. And yet, however progressive and liberatory these solutions may have felt at the time, they were all inspired by and consequent to the necessity to improve and expand the already global technology of exchange that is money.

The power of this realization about materiality spiraled modernism toward its total sublimation. In some ways we are still coming to terms with all the postmodern bubbles spun by an architectural discourse that, since then, has desperately attempted to hold onto something tangible (the regionalists, the historicists, the Pop artists and the technologists). Today, the global system of immaterial division, progressively overlaid on the existing world, has absorbed a large portion of the city. It reached a symbolic point in September of 2007 with the release of the first iPhone — as if announcing the subprime bubble and the socioeconomic era’s shift from postmodern to post-internet.

We might discuss smart devices in relation to the housing crisis, noting that the internet had at that point become an essential infrastructure for inhabitation similar to what architecture always was. Such devices allowed one to visualize the digital as a space that isn’t open but is made of immaterial walls and buffers, not unlike scrims whose borders annexed and overrode much of the existing architecture of the city, transfiguring it in the process. Indeed, the dominant technology of division of the modern city is repurposed by the new flexibility, adaptability and functionality of digital separations. However, this does not imply that material separations have lost their capacity to exclude and that all thresholds will one day be replaced by immaterial ones. This would be to forget the dramatic proliferation of border walls occurring proportionally to the expansion of the digital, which shows the inadequacy of the digital to administer bodies and things as such, especially when they don’t have the “luxury” of being included in the system. Moreover, it shows the absurdity of wishing for a totally virtual, “smart” lifestyle.

It has already been a few decades since the era of architecture’s dominance was declared over by the figurehead of the architectural avant-garde, Superstudio, as they foresaw the inevitable expansion of immaterial infrastructures. Was the city transformed, and in what way? Have there been any notable changes? The potential of the immaterial led to a series of new urban and architectural typologies, the first notable effects being the appearance of a rhetoric of liquidity and liquefaction in the architectural discourse. The impossibility of the total dematerialization advocated in the 1970s initiated a progressive search for a softer and smoother architecture, one that was deformed to accommodate flows when it wasn’t being deformed according to flows.

The guiding light of this transformation of the city from without was Zaha Hadid (this past tense is particularly heavy with her tragic passing a month ago). Hadid’s career offers a good summary of the progressive infiltration and recomposition of the urban totality by the digital. Her work seems driven toward ever-higher fragmentations and resolutions. The recourse to a liquid architecture was deeper than the literal and superficial application of the rhetoric of management that suddenly fetishized networking and interactions at the forefront of production. The appeal of sleek, curvaceous spaceships mobilized the entire spectrum of the digital beyond the mere object. Her buildings are not simply walls or even spaces made of borderless rooms organically flowing into one another with the lightness of air, but they were created with a deliberate irreverence toward any medium of existence, as the architectural presence cannot ignore its “immaterial” life as rendered projections, technical exploits and high-value images.

The conflation of all mediums into one is visible in Hadid’s paintings. The city fabric becomes a myriad of fragments, as if buildings, roads and the landscape were one identical material. The whole is exploded into atoms to reveal its unity, analogous to the unity through division promised by the digital. Like the pixels of a screen or the bits of a file, Hadid saw that our experience of the world was being abstracted into segments in order to flow better, yet without actually changing shape in the physical sense. Unlike the gridding of Koolhaas’s captive globes, which managed to freeze architecture in time but failed to represent the totalizing process of uniformization wrought by the digital, Hadid sensed that the immaterial structure could very well contain all there was, without ever producing any architecture “at its image.” Her architectural quest was to give form to the formless.

She insisted on breaking the dualism between public and private, on upholding the singular ground of modernism while mitigating it by degrees, and considered the whole discretely, because it was already underway. She introduced the gradient as a valid architectural typology because the limits of rooms had faded as much as paintings had become pixelated. Hadid’s architecture characteristically evolved from angular to curvaceous as it wrestled with the sophistication of the abstracting force of the digital. It is unlikely that her architecture of infinite dissolution was ever meant to be applied to entire cities. She was building glitches into the urban fabric, or rather mirrors that let the rest of the city see its real face.

Thus, the material separations of architecture do not fall in the presence of smart devices, which make bodies and cities smart by incorporating them in a global structure of immaterial separations. The crisis of enclosure that the philosophers of plurality and individuality had identified is not the irrelevance of architectural knowledge that Koolhaas also sees in the smart city. [Rem Koolhaas, “The Smart Landscape: Intellligent Architecture,” Artforum, April 2016] Architecture is not dead; it’s just different. The walls, the membranes, the rooms, the windows and the passages of the smart city do not perform in the same way, but these elements remain the core repertoire of architecture. The way they used to mediate relations are indeed queered by the addition of other kinds of frames and other means of emotional administration, but the way forward is certainly not the re-establishment of their classical nature through other forms of technical artifice. This evolution isn’t necessarily more profound than past historical movements, either. As usual, when the historical constellation shifts, a relevant relationality to built forms will naturally come through the sensible aspiration toward another “sentimental education.”

Nevertheless, if architecture wasn’t made irrelevant by digital technologies, it is clear that the organizational capacities of the digital, the internet and smart devices have notably impeded on architecture’s territory — that of a knowledge that orders and divides space — and has arguably emptied architecture of some of its original raison d’être. This is one of the reasons why some of the borders of the age of access can afford to become less evident in certain cases, less rigid, less present; or why lost typologies of space and décor are able to be brought to life now that the puritan rationalism of the bourgeois days has faded (or has been assumed into heaven). It is also why it is necessary to dissect material and immaterial divisions upon the same table. The digital has also established itself as an essential tool for orientation through which the world appears both spatially and affectively, thus stepping on architecture’s significance as an emotional infrastructure. It has enabled new patterns of movement, a state of permanent nomadism in space made possible by the permanence of the connections that matters, to relatives or to work, for instance. One can live swiping and surfing from one space to the next because one dwells, like the Virgin Mary, in orbit.

When living in this way, the experience of physical divisions is mostly temporary. One goes from space to space more or less voluntarily, navigating a subjective map of the city that is being constantly reconfigured. The architecture remains the same, but occupations change and fast-forward, from room to room, from neighborhood to neighborhood, from city to city. It is a state of zombie dérive wherein being lost isn’t an option, nor is being in control. But gone is the modernist aversion to materiality, which peaked with the radicals’ abolition of architecture. The relationship to walls and buffers, and to matter and media in general, is still violent, but can afford to be more intimate now that control and escape are both the result of days spent stroking a glass screen. Or perhaps it is because the comprehension of the subject has evolved toward a more ambivalent and unresolved relationship to the violence of power, that of resistance. The subject forms against forces rather than through their abolition. It needs to oppose walls and feel borders in order not only to become, but simply to be. These borders are what makes room for the Self by holding the Other back. After all, these separations, whether physical or abstract, are the only realities that the subject has to present and represent herself, the only realities that she can inhabit.

The contemporary relationship to boundaries and interfaces isn’t only more intimate; some of these thresholds are sacralized, some fairly, others less so. Think of the many incantations pronounced to perform your personal sphere: “I am a straight German vegan blond middle-class black homo with two sisters and a degree.” The performance of the self happens through the temporary identification with real abstract thresholds and, although they are not really yours, their combinatory appropriation reinforces individuality. Entertaining a good relationship with borders seems vital, but it remains nonetheless power’s ambit to impose its definitions on space, things and bodies, making the whole valuable in its own terms. Digital devices, profiles and platforms instrumentalize individuation by dividing into ever more parameters, more criteria, more elements. The more criteria that define a thing, the more it is amenable to the market since it has more degrees of comparison and exchange. Rendering life in high-resolution expands the range of life that can be potentially productive.

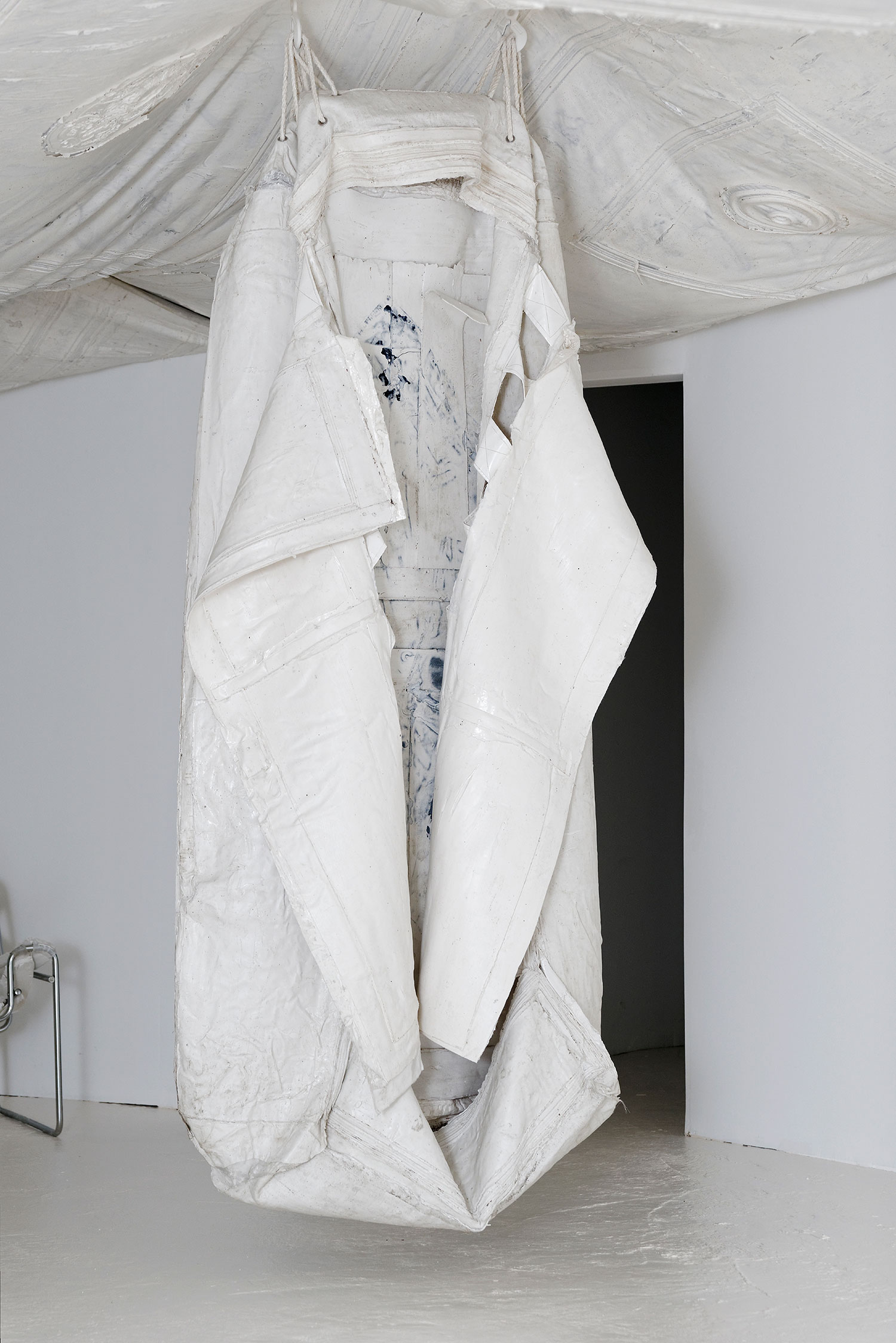

The wall as womb — a metamorphosis offered by the crisis of physicality, which opened up a whole new geometrical cosmos questioning the pure binary value of the line as it translates to spherical orbit. Immaterial divisions, 360° horizons, HDRI extravaganzas, a world without end, one who cares without reason.