The history of modern art in Korea is an endless quest to establish a Korean identity beyond Japanese modernist influence and Western movements that arrived through the vehicles of American culture such as art magazines. The tangible reality of these artworks did not reach South Korea until much later when the museum system started to develop in the late ’80s.

If the South Korean scene was dominated by a sort of modernism — because the ‘good taste’ of the bourgeoisie was and still is more inclined to ‘radical’ non-objective kinds of art: cool minimalism, zen-like monochrome paintings — the turn of the ’80s saw the emergence of a political fight for democracy that included the heroic participation of a group of artists who united under the banner of the “people’s art” (minjun). The revolutionary movements were violently suppressed by paratroopers sent by the militaristic government. Hundreds of people were killed, some of whom were depicted in huge paintings by these artists, influenced by so-called Socialist Realism.

With the return of democracy a decade later, the election of a new center-left government saw the same ex-rebellion artists under the golden ceilings of the power’s palaces. Another style replaced the former one and Erró became an heroic figure to be exhibited on the walls of big public museums.

The ’90s was a difficult time for a new generation of artists who didn’t want to pay tribute to its monochromatic predecessors or to post-Stalinist propaganda art, and who sought to establish their own areas of interest: gender, kitsch vs chic minimalism, installations and multi-media computer generated works. Lee Bul, Kimsooja, the late Bahc Yiso and Choi Jeong-hwa were the figures who struggled to break down the formal barriers and the social politesse of a Confucius-rigid society. Either in Korea (Lee Bul, Choi Jeong-hwa), or self-exiled in America (Kimsooja, Bahc Yiso), they fought to establish themselves within international biennales and globalized group shows.

The future of South Korea is our current nightmare, due to the fact that a techno-freak generation of teenagers are preparing to replace the elder generation of grayish businessmen, anonymous within the gigantic Korean multi-activity companies (Samsung, LG, Hyundai, SK, etc.). Young Korean cinema, so successful locally as well as internationally, demonstrates how one can prevail by a great strategy in a globalized world. Is South Korean visual art possibly going to do the same? The notion of Korean identity is a trap, because nobody cares about specific identity anymore, a change that is in itself a positive piece of progress against the idea of nationalism. Technically well-trained, art students now have access to the world of art. Some are even well off enough to be able to totally devote themselves to their practices. They all visit Kukje, Hyundai, PKM and Arario galleries, among others. The gallery situation is flourishing, as the galleries all have built their own spaces — three- and four-story buildings sometimes accompanied by a fancy bar and/or restaurant. There are museums on every corner of Seoul’s city center or on the southern bank of the Han River that crosses the megalopolis. Private museums are the trend, run by companies — Samsung Leeum, Daelim, Ilmin, Kumho, Sungkok, etc. — or by artists (even the most obscure masters have erected museums to their own glory). Art centers are also playing their role between private and public spaces — Art Sonje was the best example of an independent institution able to compete at an international level (but unfortunately now closed) — and the last decade has seen the emerging concept of ‘alternative space’ occupy a more and more significant place in the scene: Ssamzie space, run by the leading fashion company Ssamzie Co., as well as non-profit exhibition spaces Pool and Loop.

Confusion, contradiction and great enthusiasm are tensions dominating the contemporary Korean art scene, which is so often disappointing because a lot could happen but rarely does. Artists can help in this matter. A young generation trained abroad could bring back techniques and international know-how, capable of enriching art in South Korea.

I have selected seven artists to draw a subjective panorama of the emerging South Korean scene. This selection mixes artists working with installation with painters and photographers and, in a tribute paid to ‘new technology,’ a couple of web artists.

Haegue Yang (born in 1971) studied in Germany where she was introduced to the theory/workshop/gender/symposia practice. She is currently dividing her time between Germany and Korea. After a first period of digesting the Michael Asher era combined with a German background — she did some seminal pieces in which she explored the poetry of the street with leftover furniture in Street Modality (2001), or Social Conditions of Sitting Tables (2001), in which she photographed typical-looking pieces of street furniture — her involvement in video-diaries à la Jonas Mekas, juxtaposed with a rather hermetic narrative read in a listless voice, brought her to the urban poetry of the dark corners of cities, of non-monumental locations filmed around the world throughout her own trips to Korea, London and Brazil. It is fresh, slightly boring and simply edited, but delightful in beautiful sequences of the soft invasion of origami in the gutter of a wet street. Over the last two years she has achieved a sort of freedom, a freshness in a series of works entitled “Series of Vulnerable Arrangements” that was on view in Utrecht, in Copenhagen and in Seoul in 2006. This series culminated in an installation in Korea, Sadong 30, in which she displayed little events produced by small objects, lights on the floor, and other material thrown around the abandoned space of a house falling apart — between the romance of privacy and the openness of public address. It is clear that she is moving forward and has finally gained a certain degree of serenity.

Slightly older, Choi Jeong-hwa was born in 1961 in Seoul, where he still lives. He is one of the main figures, a sort of godfather for a younger generation, running many projects and business in Korea and abroad. He decided to live in South Korea out of a sort of pride and love for his country — aware also of its limits and heaviness. He is the one who brought — within the good taste of bourgeois aesthetics — into the discourse the issue of kitsch as a given data of the modern globalized (but Chinese-made) consumer world. Collecting cheap objects, enlarging them to the size of a monument, piling them in colorful arrangements and treating everything as if it were on the same level because anything goes, he became a great urban decorator. Seen in different international biennials (from Venice, Lyon, Liverpool, Shanghai, Singapore to Yokohama), his Fruit Tree (Yokohama, 2001) and Flower Tree (Lyon, 2003) were successful because they were direct, obvious and therefore immediately popular. It could have been a cosmetic cool and easy decoration, but he is being ironic when vaguely copying Le Corbusier’s famous cubic armchair and upholstering it with a fake Louis Vuitton fabric, or when he covers a museum building in Seoul with tons of street banners with images of fresh pizza at the corner grocery, a lottery, a concert in a park, etc., using cheap, colorful, digitalized bubble-jet prints. At the same time, he is a graphic designer, an interior designer and an architect; he recently was asked to renovate the Seoul Cultural Foundation headquarters building in Seoul. Choi Jeong-hwa totally undressed the building by peeling off the façades down to the structural concrete beams. It looked injured, deconstructed and rather impressive. He completed the rough-hewn effect with ex-train track wooden beams, used for the stairs and the floors. A postwar minimalist atmosphere created a scandal in the Foundation, which effectively blocked the project and left it unfinished.

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (founded in 1999) is a couple living in Seoul and doing web art. They met in Paris and moved back to Korea. The Tate Modern commissioned a new piece (The Art of Sleep) and so did the Pompidou Center for the artists’ 30th anniversary (Les amants de Beaubourg). Their Flash animations are punchy and straightforward. Once you have visited their website (www.yhchang.com), you can enjoy their visual and sound poetry. They glorify Cunnilingus in North Korea, or put you under the skin of a Korean (Morning of The Mongoloids). They have the critical sense of humor and touch of maliciousness necessary to live in Korea.

Jung Yeondoo (born in 1969) is a landscape artist who uses photography to give form to his imagination: recently, in a series of works entitled “Location,” he created outdoor scenes that one can see as film stills shot on site. He exhibits these stories all along the gallery walls as a number of suspended narratives. An image depicts a landscape seen through a window, past rice fields and with a mountain in the far background. All fake, all made up, mystification, betrayal, the scene is built up with a few wood boards and props displayed right on the spot: the camera frames the whole. In a past series of works, Jung Yeondoo asked school kids to draw some of their dreams. From the drawings, he constructed the sets to be photographed; they were handmade, without digital effects, just old-school photos with set designers and carpenters to help fabricate the sets.

Lee Noori (born in 1977) is a painter who tries to follow fashion and the Korean must-have: architecture. He currently paints houses cut out of coffee-table magazines. Modernist houses, not totally famous but trendy, which are good enough to be reproduced in the glossy pages of those magazines. His work is painterly in the way that extra colors, lines and traces are spread around to glorify the surface of the canvas. Architecture is a serious matter in South Korea, when anybody with a bit of money who wants to have his or her own museum, or fancy Japanese restaurant, can ask a talented ‘cut-and-paste’ young architect to design it. Wood, cor-ten steel and concrete are largely at work in these medium-sized buildings which are mushrooming up all over cities and the countryside, much to the chagrin of the ‘international style.’

Sung Nakhee (born in 1971) is a bad girl playing the serious painter as she covers walls and walls with her nervous and linear graffiti. Akin to Otto Zitko Raüme installations, where endless lines are drawn around museums walls, she constructs large linear wall drawings. Originally theorized and practiced by the Surrealists, automatic drawing supposedly allows the unconscious to rise up to the surface of a work while eschewing the notion of composition. Take a line and follow it to its end: it may go through angles, flat surfaces and dark corners, it may touch the floor as well as the ceiling and leave the room filled up with spider webs on acid and Kandinsky a fa’ presto. Sung Nakhee also paints on canvas, which makes her work more accessible to collectors, apparently.

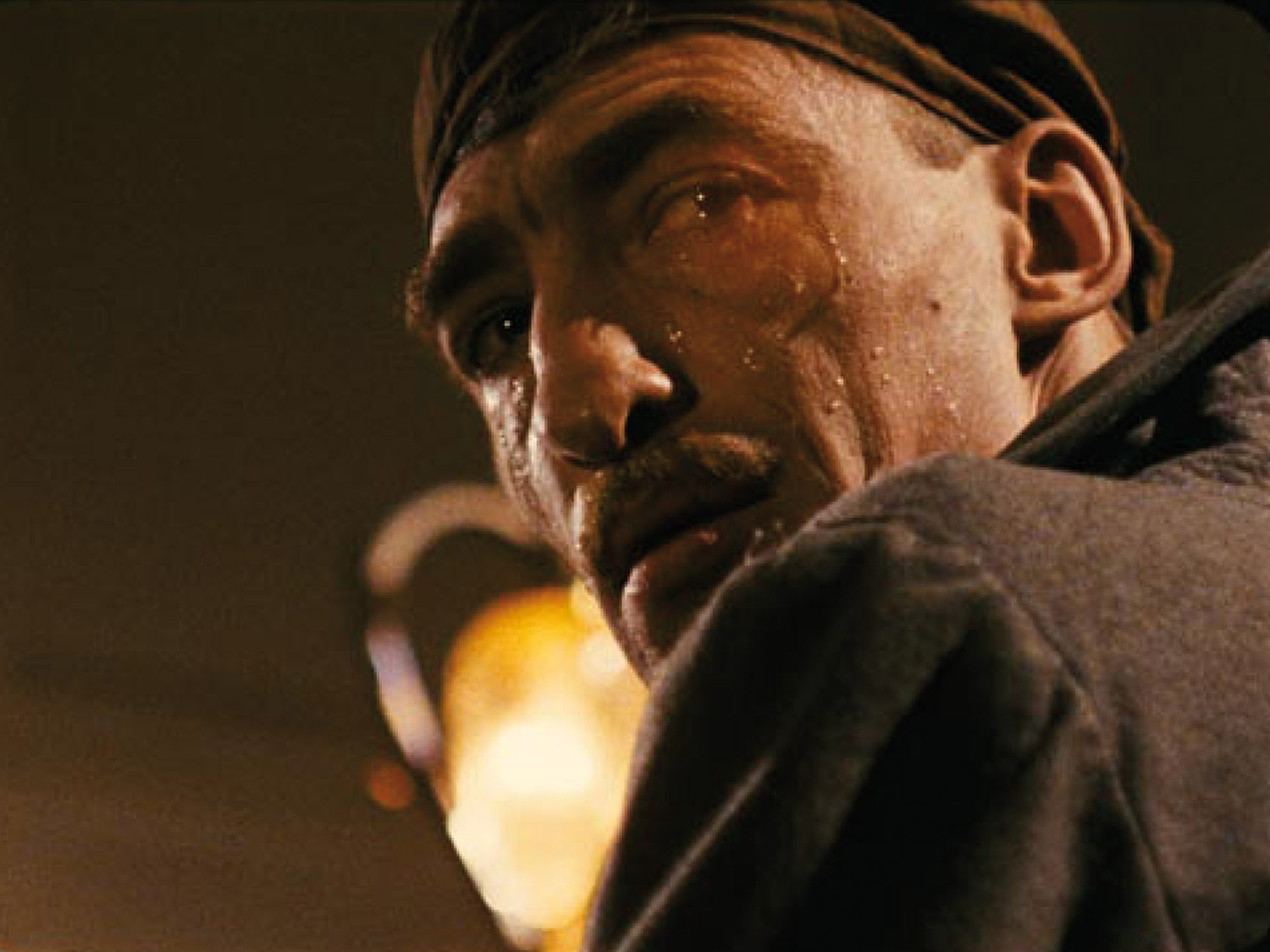

Leaving the walls for a simple small A4 sheet of paper is the will of Baik Hyunjhin (born in 1972). He is a complex character: he has been known as a musician, a film soundtrack composer, and more recently as a talented draftsman. His large series of drawings (Augustus Phrase, 2005, for instance) show black-and-white lines, contorted to suggest characters and backgrounds while some colors sometimes contradict the linearity. Recently he organized, for a group show, a whole body of drawings in a powerful installation combining overhead fluorescent lights and painted walls. He included, during opening hours, a performance in which he mumbled songs, sat in a corner and dressed as a tired and wounded boxer.