Michele D’Aurizio: In 2002 you organized a group show titled “poT” in the context of the Liverpool Biennial, which then traveled to Galeria Fortes Vilaça in São Paulo. It was concentrated on works that had a vessel form. Can you tell me more about it?

EV: The vase is a body of gracious outlines that can also hold external content. These are qualities similar to those I expect from a work of art: grace in the making, openness to associations. The vase idea came to me as a salvation after a deep creative crisis — the first “good” works of art after that period were vases made of trashed paper. So that show marks an important moment of recovery for me, especially after years of study in London. I used to have a rather assertive approach to art making, which was well received here in Brazil in the ’90s. I made conceptual drawings from pseudo memories, and thanks to that I got a scholarship from Brazil and was accepted at Goldsmiths. But there I lost everything: I told myself that what I was doing was counterfeit, and so I deconstructed everything I used to believe in.

MDA: Do you credit this to the school’s teaching methods or was it more a personal process?

EV: Much as in psychotherapy, it was personal hardship within a certain method. The school shakes up your practice. I felt lucky that I was given the chance to go through this process, and it still informs the way I tend to look at art; it’s all about motivation, where the work comes from and what drives it.

MDA: What do you mean by motivation? Are you searching for an idea? A spark? A technique of your own? A working process?

EV: I think it’s all about the process and the ethics of making. I channel my motivations to be aware of things that excite me or affect me so that I will not feel blank or disenchanted in my practice. It has to do with the first spark of a work, you are right. But then motivation also determines some “zone of truth” in the work; it guides how I position my vision of art and society within that work. Sometimes I feel my enthusiasm escalating while I work — almost a tyrannical drive. I can cope with such bursts of ambition because I do believe that the role of art in society is enormous. I feel suspicious when I see artworks that evade, that point at problems or solutions elsewhere. I believe that these works rarely lead anywhere or help anyone.

MDA: I want to understand if you seek specific figures within your surrounding environment or if the environment itself suggests things that you then convey through your art. I am thinking about a series of sculptures in which you match the shapes of human genitalia with vegetables (Missionary, 2011; Romana, 2011; Tamanha, 2011). Did you look for genitalia in vegetables, or did you end up casually recognizing them?

EV: Well, we are all attentive to penis shapes in vegetables… So it’s a figure that draws itself — it almost escapes representation. In these works the articulation of the figure and the title are a lot of fun for me. It works like a circular process that I can enter from any point. I recently made a work titled Call Girl (2013), which is a small abstract relief with a number of red and blue rectangles mounted in it. This work could be anything — it’s an abstract composition — but when I looked at it I saw a make-up set: the red is the lipstick and the blue is the eye shadow. So, starting from an abstract composition I ended up with the image of a prostitute; but it could have happened the other way around. This feels to me like a way of enriching the language of abstraction and softening the process of representation.

MDA: Indeed, when I look at some of your bronze reliefs (Text Book, 2013; A4, 2013; Livro de Criança, 2013), especially if I think of them hung in a row, they remind me of the rhetoric of abstract art. But in the end, they work more like some of Blinky Palermo’s late series — I am thinking about Times of the Day (1974–76) or To the People of New York City (1976). Like some of your works, you read the title and the title paradoxically makes the whole thing way less complex — it gives the work back to the viewer, connects it to everyday life.

EV: I agree: titles let me recognize the world in what I do. But they also help share alternative connections, demonstrating that the work is open to many other associations. Most of time, titling is the last step. But I worked in the opposite direction for an entire exhibition: “Pet Cemetery” at Galeria Fortes Vilaça, in 2008. There I started with the theme, because the theme in itself was so fascinating.

MDA: Why do you say that? I mean, a cemetery is usually a very melancholic scenario, but a pet cemetery also sounds cute. Do you have a pet?

EV: I do, I have a cat. She’s fifteen years old, and I’m constantly terrified by the idea that she will die. Probably because of that I started to pay attention to pet cemeteries. But I also thought about cemeteries as fields for sculptures. Graves are sculptures in fact; they deal with all the elements at play in sculpture: display, pedestals, etc. So a cemetery signified for me a free land in which I could include any style and language, any material and configuration. I could do anything so long as I was able to name it: the donkey (Burro, 2008), the dog (Poodle, 2008), the bunny (Henry, 2011)…

MDA: I wonder about the role of narrative in your work. Sometimes a sculpture like Romana is accompanied by triptychs of watercolors that seem to both animate the object and at the same time make more explicit the references behind it. They even reveal a formal dynamic between “resting” (Romana descanso, 2011), “leaning” (Romanadeitada, 2011) and “excitement” (Romana passional, 2011).

EV: I made these watercolors after an exhibition of the sculptures — “Missionary” at Galeria Fortes Vilaça in 2011. I had to find my way back to work after the show, and so I made drawings from the sculptures — to see them “lay down,” at rest, sensually, without their supports.

When I was twenty years old I had a conceptual project that was an attempt to explore the sexual realm: I was making drawings of flesh colors, and numbering them. I felt that, with that project, I wasn’t really able to stimulate any sensual movement, any echo of touch. I couldn’t talk about sex through depicting it, systematizing it… I felt that any sex toy could do this better than the work!

So I believe it’s important that the sculptures remain essentially useless: their sensuality doesn’t have any ambition to give sensual pleasure. On the other hand, there are physical experiences that are inherent to material as such. I guess this is the reason why, in subsequent bodies of work, in the bronze reliefs, the tactile experience is conveyed in a more direct way. Those works, without being as explicit as the sculptures, are in a way meatier and fleshier.

MDA: So with the reliefs you tried to go beyond the image of sex, to express sensuality in your own working process…

EV: …and to share it! I think that when I allow the viewer to see how deeply my fingers have gone into the clay, I am sharing that pleasure.

MDA: For me it’s always very engaging when an artist manages to reveal the process through which the work of art was made. I’m particularly fascinated by techniques that turn the work into an index of the gesture.

EV: Exactly! Your eyes are all you need for feeling the material, the malleability, the temperature, the pleasure involved or the difficulty. This is as far as my ambition can go now — to share the experience in visual terms.

MDA: What about the role of the eggs in the reliefs? On the one hand, eggs are metaphors for the perfect shape; on the other, thinking about your attention to the creative process, and you being a woman, do they connect to a sort of eschatological understanding of making?

EV: I really like that image — the making of an artwork is like an egg being plopped. I have this fantasy of making my work permanently “fertile” by creating a forest of knowledge and affection out of which works would blossom or be expelled or excreted. It’s funny because I tend to connect the image of eggs with the masculine. I’ve just given the name Boyfriend (2014) to a work with two ostrich eggs tucked into a bronze relief. The fascination with eggs started with egg cartons, which had a consistent role in the early phase of the bronze reliefs. These were actually more similar to boxes and were displayed on tables. Then I started to hang the reliefs on the wall. And that was a major move. I was very timid initially, but soon I became very excited about the additional potency, the tactile boost that the eggs and reliefs acquired on the wall.

MDA: I was also thinking recently about how wall reliefs can be physical and virtual at the same time.

EV: Exactly! And I assume that there is a collective interest in wall relief — it really embodies a sensibility of our present time, as if it answered all questions about the status of the image. I always refer to the human body as a philosophical parameter. And recently I’ve noticed that, despite the increasing diffusion of art through photographs, there is still so much travel going on around it. I mean, I’m traveling, you’re traveling — probably because we have to be with art in the flesh.

MDA: I really like a passage from an essay that Josè Augusto Ribeiro recently wrote on your work. He says that it lies “in attrition with other instances of life” [Josè Augusto Ribeiro, “A Seven-headed Monster,” in Erika Verzutti, Cobogó, 2013, p. 20]. Every time I read that passage I imagined you working, sitting at your kitchen table at night, and I felt the religiosity of that scenario, which is the scenario of creation. Do you believe there is something miraculous, for example, in recognizing a figure in an arrangement of vegetables?

EV: Art is a system that embraces miracles and magic. Nevertheless, it taps into an act of courage. You think, OK, this arrangement happened casually on my table, and I believe it’s beautiful. I want to perpetuate it, share it. So it’s a very human ambition: the desire to be “bolder,” to do something a little bit more audacious than staring at the incidental.

MDA: Does this desire to be “bolder” connect to your move from the clay of the early works to the bronze of the most recent ones?

EV: The way I communicate is through clay, so I use the bronze in order to be able to use the clay, so to speak. Today I feel very close to my early works, when I was testing the structural limits of raw clay. For my first show at Galeria Fortes Vilaça, in 2003, I started making these very banal sculptures with raw clay, as if I was a kid: snakes, cakes, ashtrays, eggs, exploring the most essential gestures that you make when you play with mud. Think about the swan for example…

MDA: I wanted to ask you about the “swan” shape, as it recurs frequently in your work. Sometimes it’s a shape from a Tarsila do Amaral painting (Tarsila com Novo, 2011), sometimes a dinosaur (Dino, 2012), a phallus…

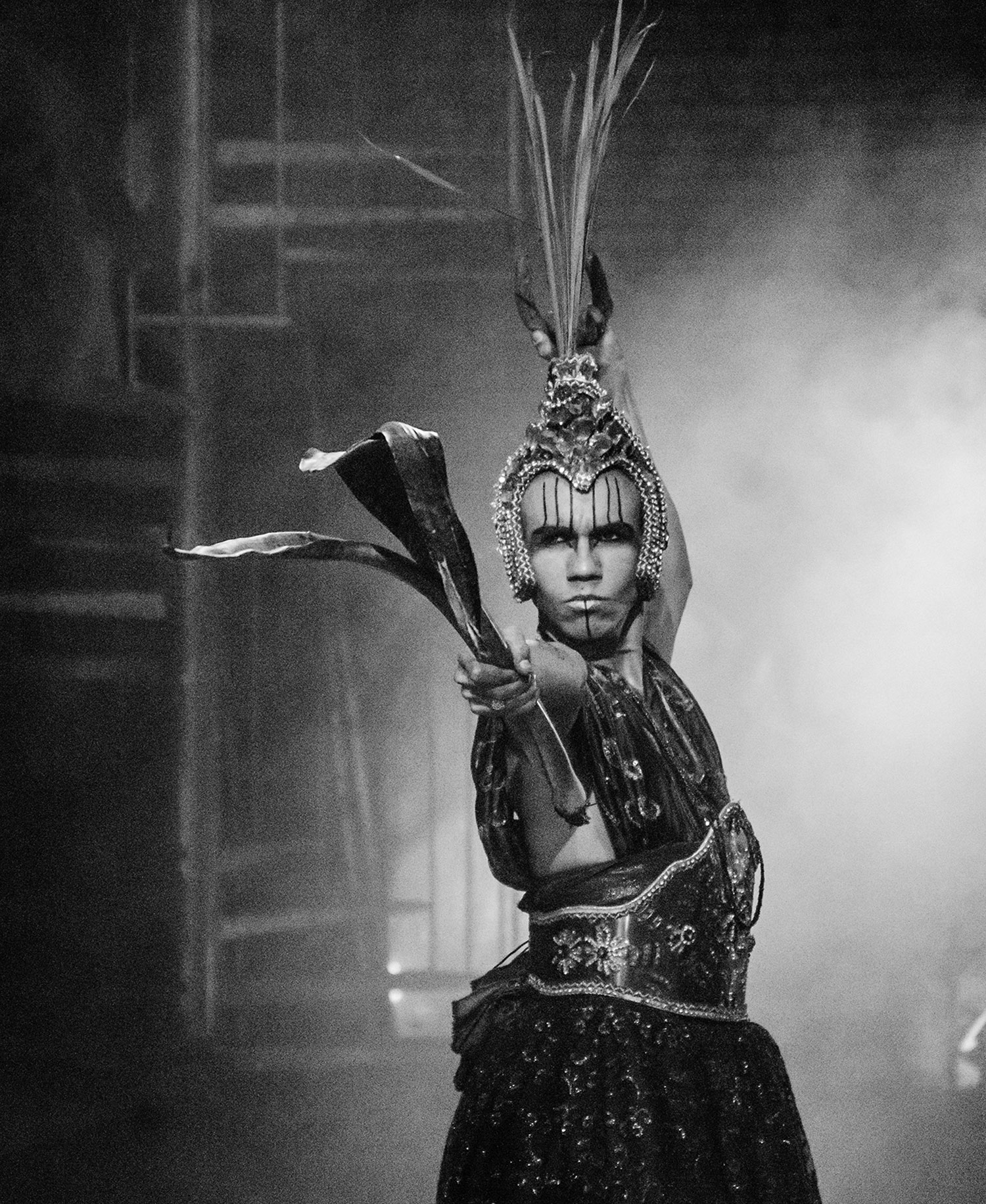

EV: They are all a unique shapes, and I’m glad I recognize this so clearly now. Because they all echo the very essential desire for verticality, which is the desire to make a sculpture. After returning to São Paulo I was lost. I spent two years thinking. And, at one point, sculpture came to me as the only direction — to be in between things, to be involved in daily life and in art as a part of daily life. So I tried to make the most elemental sculpture I was able to. And the swan shape just came. The clay wouldn’t stay up — it would bend — and so you would place a brush or anything at hand to hold it until it dries… Now I am back to the swan in a totally unexpected way. I am working on a theater play for my upcoming solo show at the Sculpture Center in New York. Here the swan will become a stage and the brush will be a human being.

MDA: You presented an early version of this work in the exhibition “Postcodes” at the Casa do Povo, in São Paulo. Does that city function like a testing ground for you?

EV: No, it doesn’t. It’s more a matter of responsibility — it’s like family. São Paulo is my hometown, and so, in a truly teenage fashion, I always do things that I would never do otherwise.

MDA: Are there peers or older artists in the São Paulo art scene who have inspired you?

EV: I like to tell this story: I was nineteen, I was studying design, and had no clue what contemporary art was. I was watching TV and saw a talk show in which Leda Catunda was being interviewed. She was showing a painting made of promotional t-shirts. I was shocked by that. So I started to follow this group of people who were active in the ’80s, and still are: Catunda, Jac Leirner, Sergio Romagnolo, Paulo Monteiro. My art came as a reaction to the art I was seeing in the city.

MDA: So, after studying in London, why did you come back?

EV: I didn’t have any money. And, besides that, I always knew that I wanted to come back. I felt that if I brought what I had learned back to Brazil, I would feel very rich here. At the end of the day, I always come back to São Paulo, despite it being a very tough city.

MDA: Does the city stimulate you?

EV: Yes, even if for me São Paulo is more about being inside places — we live without much of a horizon here. So it’s more about being in my bedroom, in my kitchen, in my studio — about feeling that I belong to a place. In the play that I am writing for the show at the Sculpture Center there is a moment when the performer translates the sculpture’s thoughts: “The swan says that he feels lonely in São Paulo.” Then the swan is asked: “Do you really feel lonely?” And that’s what I ask myself: Do I really feel lonely in São Paulo? But the answer is that I don’t, not anymore.