It’s easy to think of Dietmar Lutz’s paintings in cinematic terms, in the first place because of their frequent references to movies. “Geometry of the Heart,” Lutz’s exhibition in 2002 at Emily Tsingou Gallery in London, explicitly quoted Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Faustrecht der Freiheit (Fox and His Friends, 1975) and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (Theorem, 1968) and made its own the films’ reflections on individual relations within social structures. His recent show, in a North London warehouse last October, was titled “Querelle,” like Fassbinder’s last film — an interpretation of Jean Genet’s Querelle de Brest (1947). Like those works, Lutz’s paintings are populated by sexually charged sailors, though his figures are captured in moments with a lightness closer to Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen’s On the Town (1949) than Fassbinder’s Querelle.

Cinema itself, however, is not present in his work only as quotation of scenes and themes. Lutz’s paintings and watercolors appear sustained by a strong narrative structure: almost always inhabited by people, they resemble vignettes within a storyboard. Looking at a series of these paintings, you would be able to reconstruct the actions of the characters and fully recreate the situations in which they are shown.

The Journey, Dietmar Lutz’s artists’ book published on the occasion of “Querelle,” reinforces that impression by working as a visual diary. Divided into eight sections (with titles such as “Geometry of the Heart,” “The Journey,” “West,” “Escapism,” etc.), it could function perfectly as a traveler’s photo album, one in which the traveler had substituted the photographs with paintings and watercolors — or had made paintings and watercolors out of the photographs. Indeed, this is what Lutz does, as is evidenced by a quick comparison of the section of The Journey entitled “West” and the photographs printed in the recent book Werte Schaffen by hobbypopMUSEUM, the artists’ collective that Lutz has been part of since its inception in 1998.

Like common travel snapshots, most images in The Journey provide, together with the suggestion of narrative, a strong sense of reality. You can perfectly picture the situations, whether they show a room with an empty, untidy bed (Bedroom, 2005) or a dark-skinned man walking through an empty square with Islamic architecture in the background (The Mosque, 2004). Once again these are movie-like paintings, ones which, according to the conventions of the medium, are still obliged to comply with a very strict set of rules for internal consistency and verisimilitude.

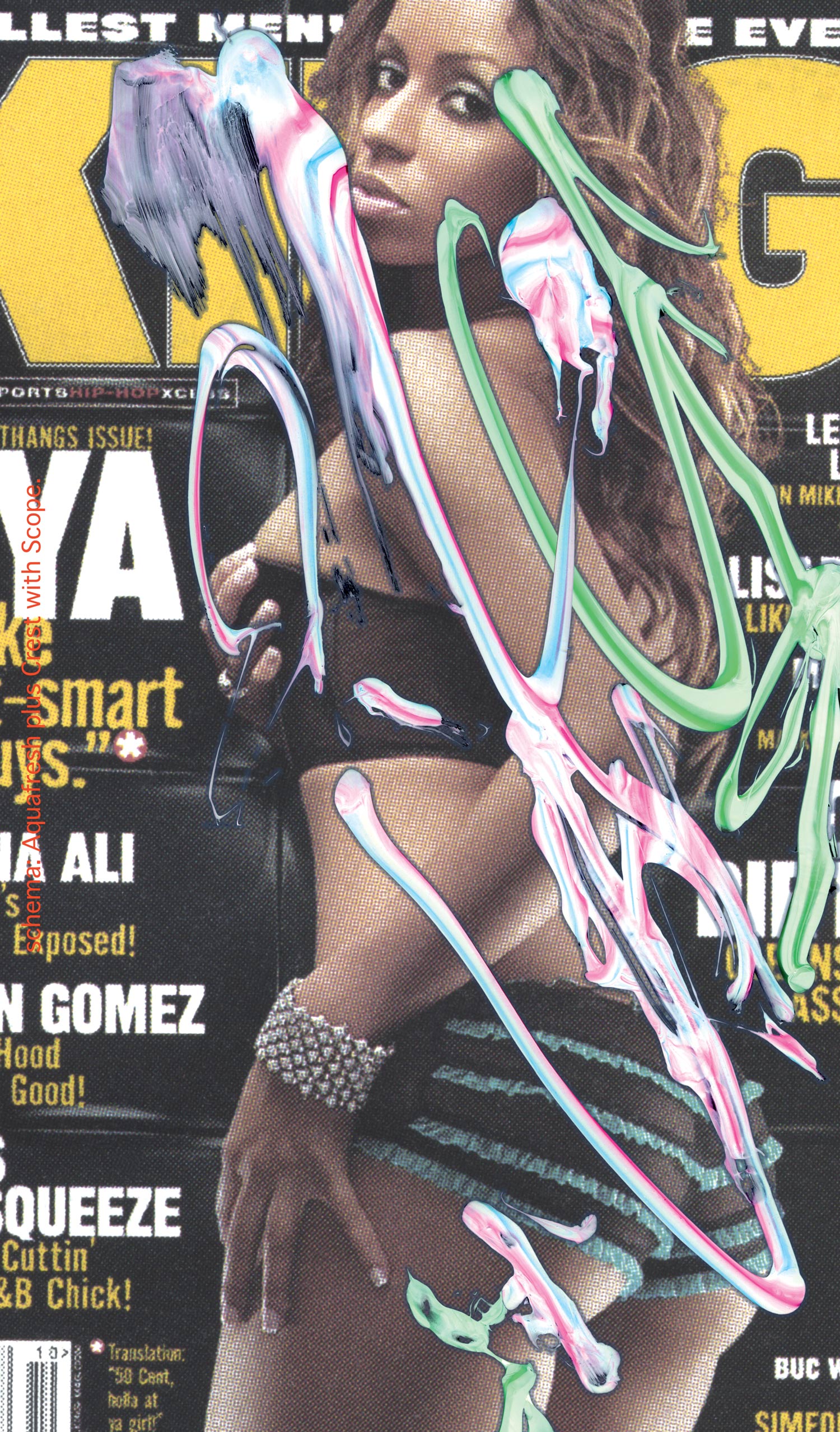

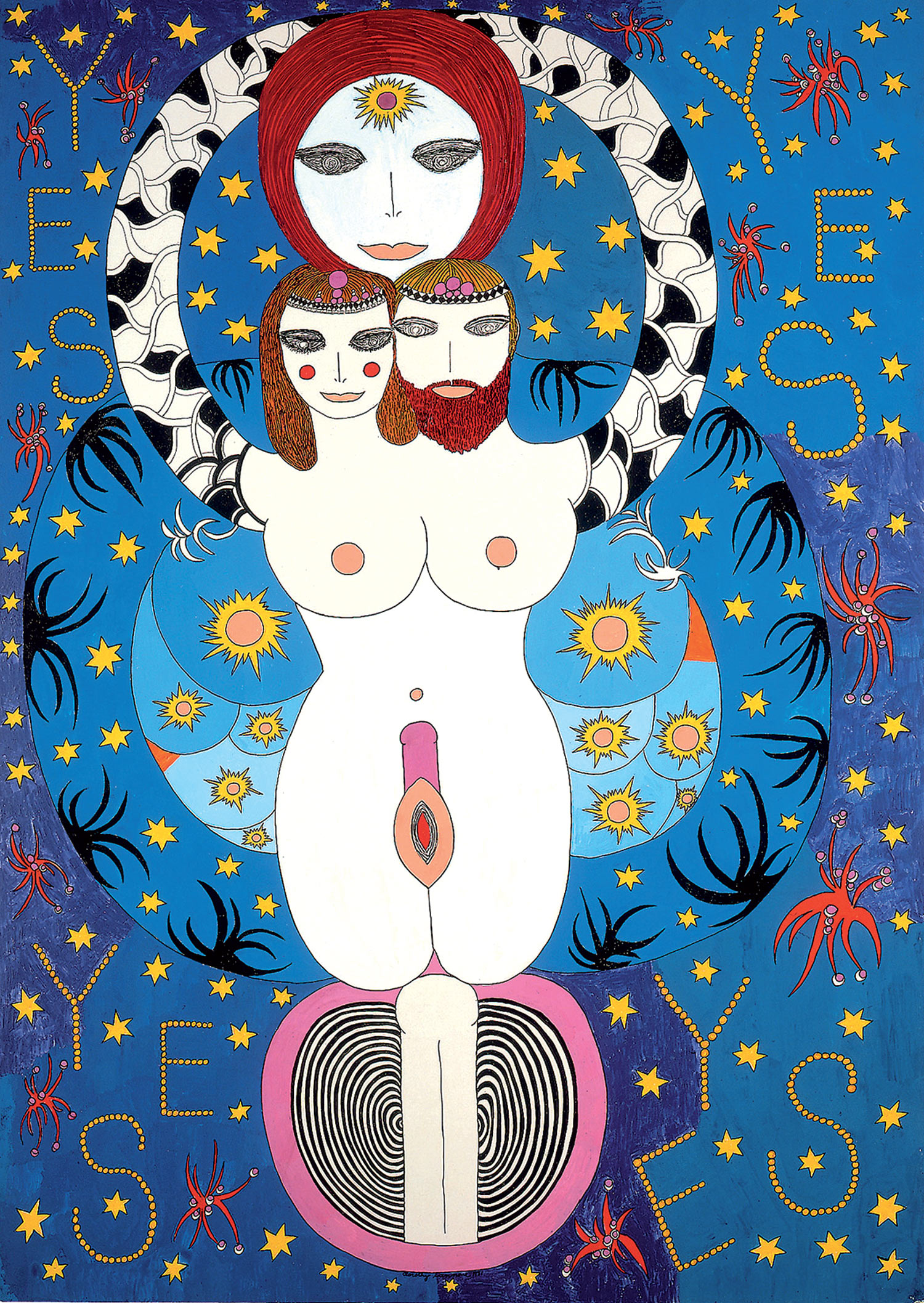

This is how paintings and watercolors appear in the book, ‘hung’ on the pages like photographs. They are not just images, they are paintings of images, and as such they question the verisimilitude that they seem to promise in the first place. That is perhaps most clearly perceived when Lutz works on images that are not originally taken by him. “Controfigura,” his exhibition at Alberto Peola Gallery in Turin in 2005, consisted of a series of watercolors and paintings centered on the male figure. Most of the images showed muscular men with their shirts off standing by classical ruins, posing in Speedos by the swimming pool, standing naked on a balcony, or photographing themselves (again shirtless) in front of a mirror. These are the kind of pictures you find in gay cruising websites, images that have been posted there for (mainly) self-marketing purposes. By titling them Double and numbering them, Lutz treats them as fictional self-portraits, as a set of different possible modes of presentation, both of the male body and the artist himself. To some extent, their point is to confirm that Dietmar Lutz’s paintings are not illustrations of Dietmar Lutz’s life — although they are different and diverse episodes in the construction of a character’s image.

“Momentum,” his exhibition at Emily Tsingou Gallery last September, reflected on the same point, but this time through repetition and variation. A collection of large acrylic paintings and watercolors based on photographs from New York street scenes, “Momentum” showed how one situation can result in a diversity of images that themselves can be associated with a variety of representations. In some ways, the series of pictures of a black man with blue shirt and white trousers waiting by the pavement while people move around him could be seen as a simple sequence in time. The difference in composition, color and brushstroke, and even in the subject matter, indicate that “Momentum” wasn’t about mere change in time, but about production of difference, both through perception and artist’s intervention.

If these aspects are not immediately obvious, it is because of Lutz’s ease as a painter. The broad, loose brushstrokes and the thin wash of acrylic and watercolor create a sense of immediacy. The characters and places in the paintings are defined with extreme economy of means, with what seem to be no more than the essential brushstrokes; but that definition is so clear that the viewer may take what is painted (and its constructive character) for granted. In that sense, Lutz could perfectly fulfill a common romantic image of the gifted genius, effortlessly creating (or recreating) through the power of his imagination. But if Lutz is romantic, it is in a different sense: as Novalis wrote in “Monologue,” language is not spoken for the sake of things, but for the sake of language itself. The same applies to Lutz’s painting: it is not about what it shows, it is about how it does. Novalis continues, “When someone speaks [and perhaps paints] merely for the sake of speaking [or painting?], he utters the most splendid, most original truths.”