Hans Ulrich Obrist: Could you talk a bit about Limit of a Projection?

David Lamelas: This is a piece from 1967, originally shown in Buenos Aires for an exhibition called “Más allá de la geometría” (Beyond geometry) at the Di Tella Institute.

HUO: The 1960s in Argentina were an incredible moment of radical avant-garde.

DL: It was very radical but we were also very lucky because we had an institution where we were allowed to show this kind of work. For example, for this show each artist was paid a small amount of money to do the work, which was something very new at that time. The idea of the piece came because I was in the process of getting out of the object.

HUO: Can you tell me about your first show?

DL: My first big show was an installation titled “The Superealistic,” which already moved into space as an installation. It had color and it was in relationship to architecture. I got rid of color and at the end I got rid of the volume of the object. That’s where this idea came from: to make a work that doesn’t exist as a material thing. The idea of the light had that quality. But I also remember, even as a child in a cinema, I would pay attention to the film projector. The gap between the film projector and the screen is usually a very large space that creates a cone of light, and on the face of the screen you have the projection. I was very interested in what was happening to the light between the projector and the screen, so this piece is a materialization of that process. But the idea was not to project any images, just the light itself.

Pierre Huyghe: Your work has a relationship with the situation; if someone enters the room and passes within the cone he becomes suddenly exposed and exhibited.

DL: Yes. In this case what was really interesting to me was that if you go to the cinema the cone of light at the end projects a movie, and when you go to big museums it is usually to show a very precious piece of jewelery or precious sculpture. So the idea was just to show the medium itself.

PH: It is an exhibition device in a certain way.

HUO: Can you tell us about this piece in Venice, the News Room piece?

DL: In 1967 I was invited to represent Argentina in the Venice Biennale, which was also very unusual. I was only twenty years old. The reason why I was invited was because in 1967 I won the São Paulo Biennale Prize, again with an installation about space.

HUO: Can you tell me more about how you got rid of objects?

DL: I was working with the idea — coming from sculpture, let’s put it that way — of getting rid of the sculpture object. The idea of the mass media was growing among young artists in those days. I was not the only one; there were other artists in Argentina working with the idea of Marshall McLuhan or Roland Barthes, with the dematerialization of the meaning of the world or, in fiction, people like Marguerite Duras and the idea of destroying the idea of fiction.

HUO: Was nouveau roman important?

DL: Yes, nouveau roman étais tres à la mode and I was a victim… It was our passion. When I was invited to represent Argentina at the Venice Biennale I didn’t want to do anything that was within the art world context. No painting, no sculpture. So the idea was to break out from the context. Then I decided, following my idea — but following the idea, as I said, of McLuhan and Barthes, etc. — to get out of the pre-existing structures. I wanted to have the art space in the Venice Biennale not to be used as a physical space but as a center of communication. I was already working with the idea of the present moment, so I decided to have a newsroom about the most important news of the moment, and it happened to be Vietnam. It was not because I decided to do Vietnam as a political comment, but because at that moment it was the most important news chosen by the media. I became a regular client of ANSA, the Italian news agency, and they sent all information they received about Vietnam into my News Room in the Venice Biennale. It was behind a glass (a vitrine); the office looked like an exhibition room to the people outside the glass. A receptionist would receive faxes and read them to the visitors of the exhibition area in five languages. That was the idea of the different levels of information, how the news gets transformed and transported before it gets to you.

PH: The question of the narrator and the temporality are central to your work, as an active form of translation.

DL: Yes. You looked at something that was happening in Vietnam and a journalist wrote about that event, then it was re-written in Italian and re-translated to the clients and it was re-represented by the spokesperson who read it as the news. The space of the information. For example, now I am talking to you; there is space between us. Space was the important thing. It’s the same in Limit of a Projection — the space between the light projector and the floor. That is what really matters. The rest is all fiction. If people want to be photographed, that is up to them. That was not my idea, to be a showcase. I was very surprised when I first showed that piece in Argentina. It’s true, some people jumped into the light and they became like stars, but to me it was a shock because it was not my intention. It was a minimalist idea. I want to have a concept and go to the lowest level of representation to do it. If somebody wants to be photographed in the spotlight, that’s full of meaning but the meaning is created by the audience, not by me.

HUO: Maybe we could come to your obsession: Bioy Casares!

DL: I read The Invention of Morel when I was a teenager. It was a book I always liked. Later I became interested in the idea of working with light, then with information, then with the idea of fiction. I call my film The Invention of Dr. Morel but the actual novel is The Invention of Morel. He is a scientist. In Dr. Morel he created a machine, a movie camera like this movie camera [refers to camera documenting interview]; we can think that you are Dr. Morel. You are Dr. Morel, you are taking my image, but you are also taking my soul. When Dr. Morel created a camera, he photographed people, but not only did he take a three-dimensional photograph, he also took my present, my present me.

HUO: Austrian scientist Anton Zeilinger, who talks about teleportation, says that the problem with it is that once it is transported the original is gone. Does it mean that if it captures the soul, the soul is gone, or is the soul in two places?

DL: That was a question of the whole thing: whether these people have a soul or whether they have no soul.

PH: Once you record by the machine it is like —

DL: — you become an image, it will be always eternal, that will never age, that will never be transformed.

PH: There is a superimposition of the real and the image, sometimes two suns appear, the actual sun and the sun recorded by the image.

DL: Exactly.

PH: In this island you have a kind of doubling, a permanent distance.

DL: Yes, but the tragedy of that is that you always live in the present; you have no past and you have no future. You only remember the moment that the camera is taking your image; this moment is taken by you so it is not future and it is not past. But then each time that this is replayed is always the present. As for Bioy Casares, he was somehow seduced by my idea, and then I managed to put a production together. The project was ready to go but in the end it didn’t happen.

HUO: Can you, maybe in a few words, tell us what was the project of that unrealized movie?

DL: The movie was realized! It was made as a medium feature, as a short movie. It was beautifully made in Berlin with three great actors. The feature film was unrealized.

PH: When was it made?

DL: It was made in ’98 or 2000. 2000 I think, but I started in ’98.

HUO: You talked at the beginning about the “limit of a projection,” but this leads us also to the limit of the art world [. . .] You faced a limit of the art world and out of the limit of the art world you went to Hollywood.

DL: It brought me to another limit; it was the limit of Hollywood.

HUO: But the question is: Did you — and this is really my main question in relation to that — when you went from one limit to the other, did you have the idea to abandon the art world and go into Hollywood or did you think of it as a parallel reality?

DL: I saw it as a parallel reality, jumping into another.

PH: With the shift from the art context to the usual feature film context, how did you keep your relation to narration, to your characters?

DL: As an artist I was working with narration, but it’s not the narration that the movie industry needs because nobody understands my narration. Even though I did try for a while, I didn’t succeed because I realized you cannot transform yourself. You have limits, too. You cannot really go beyond that.

HUO: But you did things in these fifteen years?

DL: I did many things. I worked a little bit in television and directed television shows and I also did what I think is my best work in L.A. I made several videotapes, some with Hildegarde Duane.

HUO: Was that broadcast on television?

DL: They were broadcast on public television and then shown in museums and galleries. I created a fictional talk show called Newsmakers. Newsmakers has a host, a character inspired by Barbara Walters. My character’s name is Barbara Lopez and she is like a liberal American reporter and a Democrat, who introduces very reactionary, usually right-wing politicians. It’s about the clashes of ideology.

HUO: It’s very related to what you just did in Venice…

DL: I know. And it’s always in relationship to international news regarding how American systems of information view American foreign policy. So there is always a relationship. They are always in relationship to major crises transformed into spectacle. Each tape is like a TV show. My last one was made a week before the Iraq war started. We didn’t know that the war was going to happen. We never really believed that it was going to happen. We made a fiction that the war was going to start and never end. The reality is what is happening.

HUO: Other things you did in those fifteen years were two feature films. Pierre and I were very curious to know more about these.

PH: Not so much about the content, because we know that, but about how you translate or extend your practice to feature film. Did you need suddenly to redefine what a character was, increase the narrative, find another address, format…

HUO: Pierre said that you brought in the idea of character very early on in the art world. Maybe we should explore this a bit more.

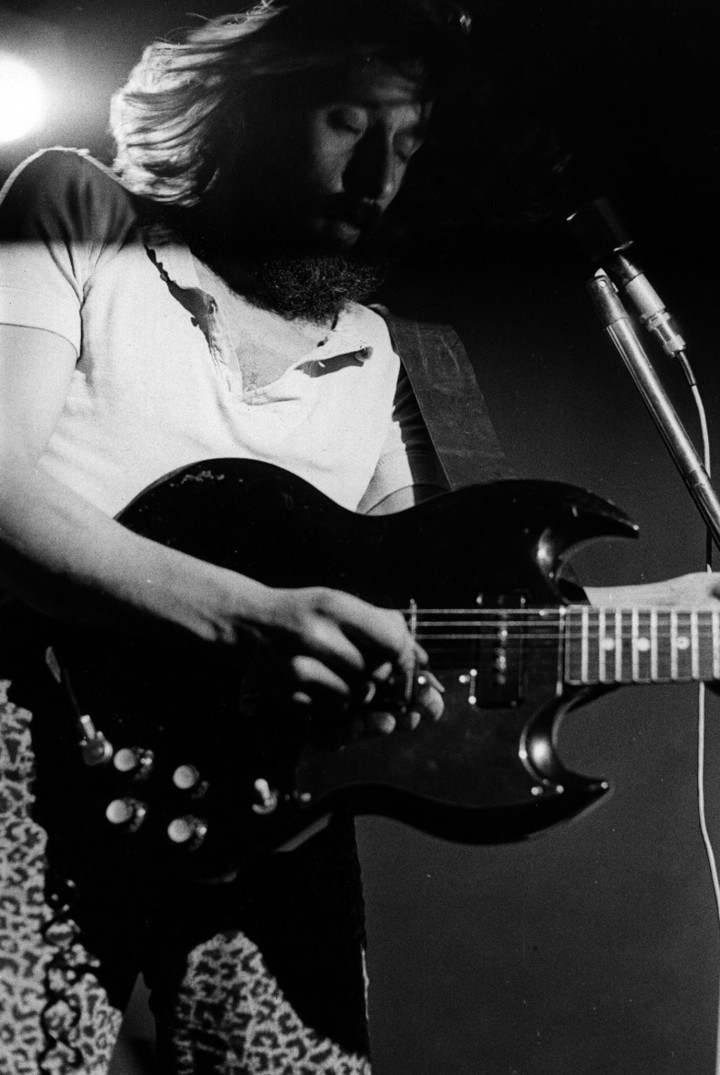

DL: The idea of character. Yes, I tell you what, I give you a character. The idea of character and the idea of personality too. Today the idea of the star, the celebrity, the political person, the famous artist, the great chef, all the representations of our culture creates this myth. That’s why when I made my piece Rock Star I carried the appropriation; I transformed myself into a rock star.

HUO: What year was this?

DL: 1974. It was the high time of rock ‘n’ roll in England. Everyone wanted to be a rock star; it was the ultimate, you know. I felt I was an artist, it was OK. So what? You want to be a rock star. Then I realized, all you need to be a rock star is to be photographed like one.

PH: So you did this image, a man with a guitar under a spotlight.

DL: Yes. And now, years later, when people see the photo they say, “Oh, I wish I’d seen you then in concert.” It gets to a point where I don’t say anything: I leave them with a fantasy. I don’t say it was a fiction; it’s like fiction took over. That’s the interesting thing. And it’s something I always pay attention to in politicians. Don’t forget I was born in Argentina from Spanish parents who escaped Spain, from Franco. He created a political as well as a media strategy to succeed as a politician. And then I was born at the end of the Perónese era when the Peróns manufactured another image of themselves to become popular, especially Eva Perón who created the model of the female politician. So from a very early age I saw the fiction in those politicians and how people bought the idea. She was a goddess because she was blond, dressed in Christian Dior and beautifully photographed.

PH: That’s why Morel is also coming back again and again.

DL: Exactly.

PH: “How do you become an image?” links these politicians, the rock star celebrity and your obsession with The Invention of Morel. All expose themselves, go under the light to become an image, a character under a certain narrative. But as the light goes, it could be a flickering position.

DL: I have always been very interested in politics and how political structures function, and I realized that the structures of politics are very much about the structures of fiction coming from Franco, Mussolini, Eva Perón, to persons of today that we don’t want even to name. It’s always about the structure. The first thing they do when they want to destroy politicians is destroy their image. Look how they destroyed the image of Saddam, for example. He always glorified himself as this very elegant, well-dressed man. The first thing they did to destroy his image was to show him washing his socks. That is very powerful; people connect their idea of the fiction with banality. It can be a very profound and deep thing because the power structures of control are manipulated. I think once you understand how the structures of power work, then you are free. But politicians want us to be trapped by this machine.