First comes the artwork and then the artist, or that’s how it was in antiquity. Today, however, the system presumes to make prepackaged intellectual human beings, ready for consumption. The artist, the new apprentice jester, is thus called upon to produce fine commercial merchandise, offering satisfaction to sophisticated palates.

It has been almost three decades since the artist renounced the duty to create. The appropriation of images from consumer society and the revival of expressionism lead the ’80s, while the ’90s were divided mainly between the crude realism of the Young British Artists and the Utopian desire of Relational Aesthetics, risking cynicism on one side and populism on the other. In both cases, we witnessed a never-ending sense of ‘whatever,’ a steady stream of ‘sensational’ cultural gadgets. Following this decade is a generation of artists raised in the shadow of Koons and Kippenberger, whose primary aims have been neither to create nor to produce: Distribution and Dispersion are the sole goals; “commodity” and “agency” are the keywords to be considered above all. “Ethics becomes self-policing and self-management. What are ethics beyond convenience, adjustment and effectiveness? Self-monitoring?” questioned Merlin Carpenter in the unputdownable text The Tail That Wags the Dog. He was definitely right.

However, for better or for worse, these times are over. We no longer see art ‘swiped’ like credit cards; this is the death of dematerialization — we are finally back to basics, dreaming of something unique and magical. “Form Follows Function” — not “Fiction” — as put in a fashionable show of some years ago. The aura will return from the persona to the object. This is the end of the Commodity System and the beginning of a constellation of Talismans; finally, a trope that comes from Art History (Le Talisman by Paul Sérusier) and not from marketing. Let’s avoid Setting a Price — no more collaboration, no more performing for its own sake, no more branding, and above all no more White Cube: aseptic spaces where any kind of object could acquire some sort of interest. This is the end of “throw-away art.” As art now means only conceptualism and readymade, let’s be crafty — let’s substitute “Art” with “Craft.”

A remedy to this aftermath is a group of twelve artists living and working in New York. Visiting their studios — yes studios, no laptops around — I envision them as Modern Crafters or Conceptual Artisans. They have gathered around Guild & Greyshkul, an artist-run space, a commercial gallery and most precisely the rendezvous for this community.

Guild & Greyshkul’s founders Sara VanDerBeek, Johannes VanDerBeek and Anya Kielar have been championing these issues since the very beginning.

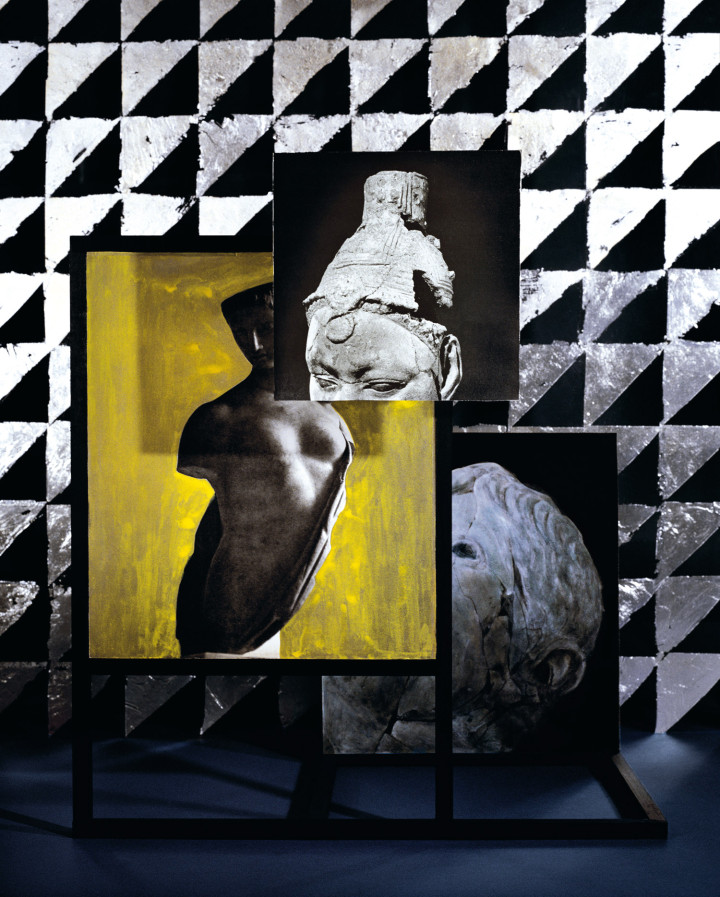

“[Sara] VanDerBeek’s instincts are those of a collector — a cataloguer, an archivist, a keeper of images — and this compulsion to save otherwise discarded or potentially forgotten representations of the past makes time tangible” (Anne Ellegood). Underlining an interest in collage in a broader sense, like his sister Sara and father Stan VanDerBeek — but also like his peers Francesca di DiMattio, Ernesto Caivano and Ryan Johnson — Johannes’s full scale sculptures made of papier-mâché, composed of old copies of Time and National Geographic, allow the possibility to have, according to the artist, “seamless joints between disparate images, creating absurd scenarios that look as though an anxious Roman fresco assistant made them.” Using historical techniques, Kielar describes her fashionable friezes and reliefs as “living corpses made from the stuff of life, things I use and collect, shadows hiding behind more specific representations of femininity.”

The representation of decay from a continuously digested past is staged by Ernesto Caivano’s refined inks on paper. His work could be considered a DJ set meant to spotlight the tradition of so-called Art & Craft, “injecting” Hokusai, Medieval illustrations and comic books within our bric à brac contemporaneousness.

The body, considered as a pure three-dimensional item, is the core of Mariah Robertson and Jamie Isenstein’s oeuvres. With a position based in self-confidence and irony, Robertson’s use of the flesh betrays a devotion to experimentation with photographic technique, though apparently without the self-seriousness that implies: a dangerous marriage between Man Ray and Saturday Night Live. With the same ironic flavor, Eisenstein makes “perfurnitures”: a mix between “performance” and “furniture,” the term was coined by the artist (as a response to a question I posed to her during a studio visit) in an attempt to define a practice that deals with the possibility of extending time (an “attempt at immortality,” in the words of Gino De Dominicis) through the objectification of the body.

Garth Weiser and Francesca DiMattio’s practices are complementary redefinitions of formalism in painting: a crash between abstraction and figuration. Weiser’s acrylics on canvas are schematic and pristine: indeed, each piece builds up an encyclopedia of patterns, grids, lines and shapes. At times executed over discarded paintings of Weiser, DiMattio’s work “speaks freely about both the painting of London school artists Francis Bacon and Frank Auerbach and the more intimate still lives of Chardin and Morandi” (Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn).

Working with sculpture, Halsey Rodman and Ryan Johnson propose a peculiar reinterpretation of this seasoned medium. “Halsey’s work can sometimes seem disjoined and obscure […] his art still manages to touch the supernatural, science, the ritual of exhibition, and even the afterlife” (Jerry Saltz); in a similar way, Johnson’s obsession for Eadweard Muybridge (“not art, not science,” summarizes the artist) and decay from various eras — Egyptian, American Secessionism and Etruscan, to name but a few — are then practically and conceptually kneaded in order to be transformed in beautiful and delicate pictorial totems, or in some cases, cut-n-paste melancholies that would have done Dürer proud.

Applied Art and collective memory in all their forms: Ohad Meromi and Lisi Raskin, who have been protagonists of many debates during their time at Columbia University, share many interests. Among these are a common fascination with alter egos (Meromi a.k.a. Joshua Simon and Raskin a.k.a. Herr Doktor Wolfgang Hauptman II) as well as an attention to every single aspect of their practices, including the publication of artists’ books such as Meromi’s Who Owns the World? and Raskin’s Thought Crimes. With results that are as similar as they are complementary, Raskin and Meromi dig into their roots (Israel for Meromi, U.S. for Raskin), proposing philosophical interpretations of sociological cases for the comprehension of the human being, e.g., the subway and the power plant for Raskin and the kibbutz for Meromi.

Today, May 25, 2009, I run into Rob Teeters and he confirms that these attitudes are now common property of any number of artists: Amy Granat, Matt Keegan, Richard Aldrich, Carol Bove, Dana Schutz, Steven Claydon, Ry Rocklen (and the former Black Dragon Society), Aaron Curry, Thomas Houseago, Sterling Ruby, Djordje Ozbolt, Mark Barrow, Ruby Neri but also Karla Black, Lorna Mcintyre, Latifa Echakhch, Pierluigi Calignano, Alessandro Roma, Riccardo Beretta, Cleo Fariselli, Alice Mandelli, Alice Tomaselli. Gaps find their way into the text even while it is getting itself written. This Crafty Modernity, in fact, has already started.