Sometimes the unexpected has to be looked for between the lines; something comes your way and nothing is anymore what it seemed. The Ian Hamilton Finlay show, spread out between two perfectly complementary venues, surely makes this case.

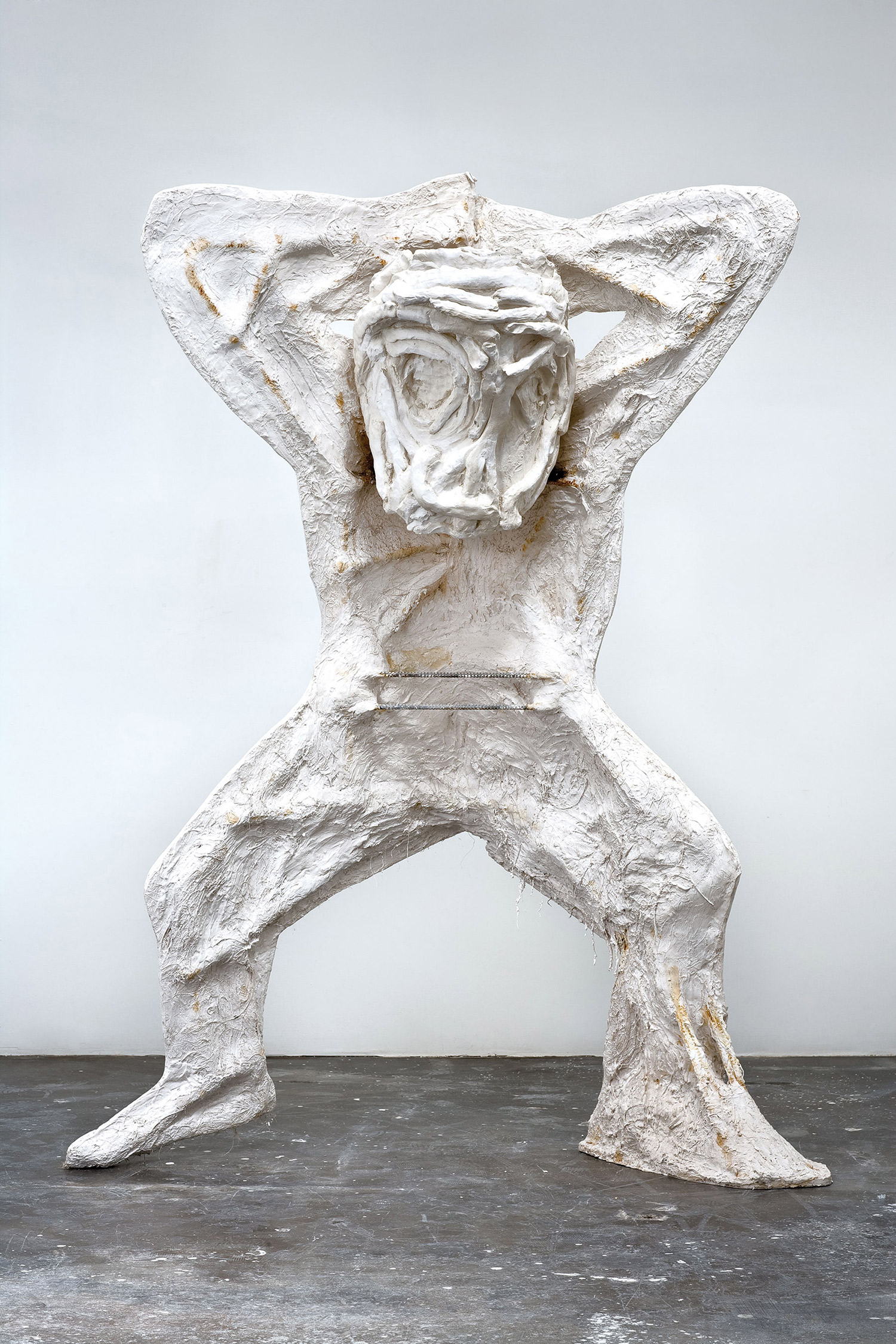

Entitled “Camouflage,” the show took place in the little project room of Paul Kasmin Gallery and the bright-white-cube-with-a-yellow-exterior of David Nolan Gallery designed by unrequited art star Richard Artschwager. The show evoked Arte Povera artist Giulio Paolini, not only for its use of Greek statues — as in the plaster replica of the ‘Westmacott Ephebe’ re-contextualized in Man With Panzerschreck (1993) — but also its refined intellectualism with an inside hint of guerrilla. A passion for Greek mythology could help the visitor feel at ease with the artist’s oeuvre, for example when approaching works like Dryad (with John Selman) (1987) or Age Quod Agis (Rubbing Post for a Wild Boar) (1997), which has direct connections to Sebastiano Serlio’s Five Books about Architecture. “What you are doing, do thoroughly,” reads the inscription on top of the work.

Between the lines, beyond those columns painted with famous military patterns, the show continued at Paul Kasmin Gallery where, displayed in a vitrine, were Finlay’s printed works from Wild Hawthorn Press. The artist founded the press with Jessie McGuffie in 1961, mainly to introduce contemporary artists to Scotland. Over the years, it became the exclusive channel for the distribution of Finlay’s printed works. Within this show — by an artist who was also a writer, gardener and concrete poet — one of the most intriguing elements was the use of the Greek word ‘poiesis’ (meaning ‘making’) for his sculptural work.

Another project that exemplifies the trans-disciplinary character of Finlay’s career is Little Sparta, a garden he created with his wife outside Edinburgh in the ’60s where he set his inscribed objects alongside flowers, trees, grasses and bodies of water. The connection to Efialte’s Death (1982), created by Anne and Patrick Poirier for the Celle’s Farm collection in Prato seems obvious, although, looking between the lines, the latter seems somehow lacking. Little Sparta can be considered the artist’s greatest epic poem, and the preservation of it by Little Sparta’s trustees — including Stephen Bann, Magnus Linklater and Victoria Miro — is of extreme importance for the legacy of the artist and for his country. It also expresses another type of collaboration that is characteristic of Finlay’s oeuvre: reading (this time) between the captions’ lines reveals names like Catherine Lovegrove and Peter Coates accompanying the work on view at David Nolan, as well as local Scottish craftspeople with whom Finlay collaborated during the creation of the stone sculptures, bronzes and prints.

Finlay was interested in the French Revolution, but perhaps he would not agree with a peculiar appreciation of his oeuvre that brings with it the same thrill, the same excitement as for Jacques-Louis David’s. In line with the French master, Finlay’s work is a perfect marriage between pure beauty and social commitment.

Plato’s motto seems to suit the case: “kalos and agathos and all such.”