From Flash Art International no. 140, May–June 1988

Although his adventuresome images and life are extraordinary, William N. Copley (1919–96) has always been an artist’s artist — celebrated by the cognoscenti but unknown to broader audiences, particularly in his native United States. Abandoned at birth, he was adopted by newspaper and utilities moguls and reared in luxury in Aurora, Illinois, and San Diego. Rather than flunk out of Yale, he joined the army in 1941, seeing combat in Italy and North Africa. Returning to Southern California, rattled by the war and experimenting with journalism and leftist politics, he was introduced to Surrealism by his brother-in-law. It was a revelation, he wrote, that “made everything understandable.” In a few short years, starting in 1948, he opened the West Coast’s first gallery dedicated to the movement, amassed one of the world’s best collections of Surrealist art, and set sail for Paris with Man Ray and Juliet Man Ray, where he spent eleven years painting full time.

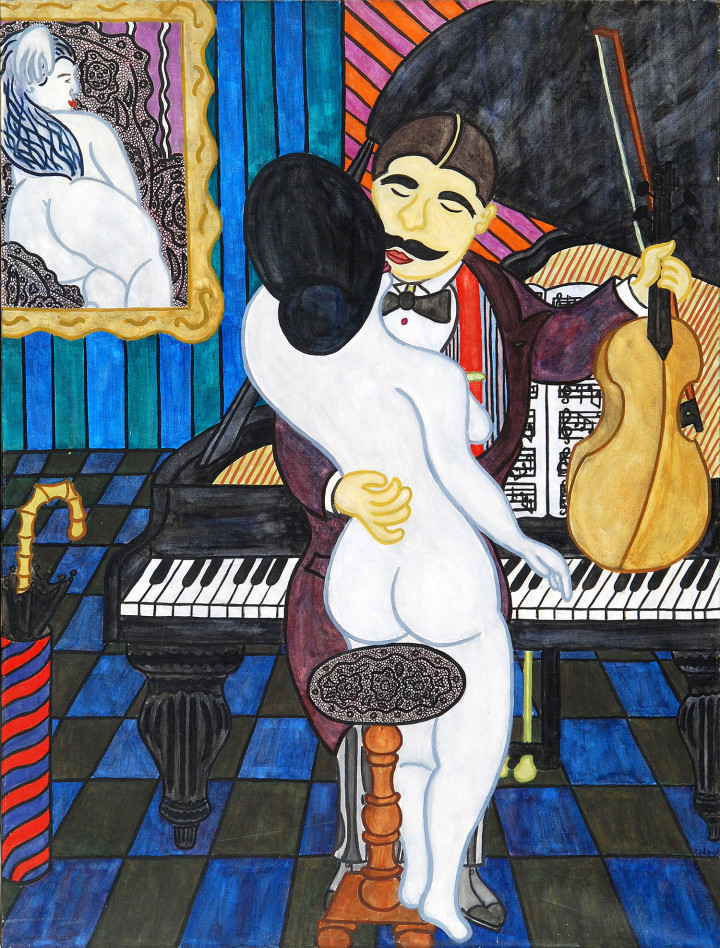

Going by the nom de plume CPLY (one writer hypothesized he used up his “Ohs and Eees” ogling the female subjects that overflow from his paintings), Copley was both insider and outsider. Filled with relentlessly inventive sendups of nationalism, morality and the battle of the sexes, his ribald, self-taught figurative styles put him on the margins of art-world good taste. Copley’s activities as a friend and patron of fellow artists, however, repeatedly put him at the center of things. His Cassandra Foundation sponsored an important series of artists’ monographs edited by Richard Hamilton and conveyed his hero Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés to the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1969. And his mail-order S.M.S. (Shit Must Stop) artist-multiple portfolios of 1968 subverted a newly rapacious art market.

British Surrealist Roland Penrose remarked that Copley’s images were the envy of his peers because they were so direct. His rejection of all pictorial refinements, Penrose observed, gave his stock motifs, including “umbrellas, hats, chairs, pianos, automobiles, flags, bidets,” a “personality and significance like an apocryphal beast.” In this late-in-life interview with Alan Jones, his most candid and considered, Copley discusses his inspirations and his working methods.

Alan Jones: Friend and patron of artists, gallery owner, publisher of a magazine, you have been an artist for over forty years. How did you first begin painting?

William N. Copley: I started off wanting to be a writer, but after reading James Joyce I concluded that the problem with my writing was its lack of imagery. So I decided to try painting, just to see if I could stimulate myself along those lines. But I started liking it too much and never went back. And I do know how to write, but I still don’t know how to paint. Had I taken it seriously I don’t think I would have had the freedom that I started with. I guess that’s what saved my life. If you know what art isn’t, the whole world is before you.

AJ: With writing as your point of departure, how did narrative methods function in your work as a painter?

WNC: Magritte answered that best. It has to do with assembling images. Certainly not so much by chance, but with intent. And I mean, in the case of Magritte, the assembling of images accomplishes a tremendous expansion of awareness, by associations that open the mind to subtle relationships. For a long while I employed a sort of private mythology in my own work, like the cast of characters in a play. I rolled them out like dice. One thing I’ve always admired is Pre-Raphaelite painting. It is narrative, and you can fill in the gaps any way you want. There used to be a guard at the Tate who would catch you looking at the Pre-Raphaelites, and he’d jump out and start to explain them to you with the most hilarious theories.

AJ: Eroticism, Surrealism’s leitmotif, appears in all your work, including the Tomb of the Unknown Whore (1965) exhibited at the New Museum in New York in 1986. Has sex always served as your central subject?

WNC: What other subjects are there? Painting is just the next best thing. It’s kind of the same, anyway. Both the Large Glass (1915–23) and Étant donnés (1946–66) are Rube Goldberg copulating machines. The “unknown whore” is certainly as important as the “unknown soldier”: they’ve both been had. Everybody forgets that a prostitute is a woman before she is a prostitute. We have a way of putting people in categories and keeping them there. A soldier is a man before he puts on a uniform, and what is more ridiculous than the “unknown soldier”? Anyone who lets himself be killed in a war deserves a monument to his stupidity. It makes as much sense as dying in a car crash.

AJ: The Tomb was not without its controversy at the New Museum.

WNC: I’m very grateful to Marcia Tucker for sticking by me for that one.

AJ: Your recent exhibition last spring at the Phyllis Kind Gallery, New York, demonstrated continuing innovation. How has your working method evolved?

WNC: Lately I’ve changed my way of working by trying to depend much more on the subconscious. I start a painting and just leave it. I know there is bound to be some subconscious event, so I don’t stand and worry what to do next. I walk away from it. This was a big step for me. It got me away from my own formulas.

AJ: This procedure recalls the conscious nonchalance of Duchamp.

WNC: Duchamp emphasized the balance between yourself and random chance. He had demonstrated that in the Large Glass by using a toy cannon. He dipped matches in paint and fired them at the glass, aiming where he wanted the paint to go, but knowing that the toy gun was very inaccurate.

AJ: Line has always been an important element in your painting.

WNC: Yes, but I don’t know how it comes about. I’ve never tried to draw. I don’t know how to draw. Picabia serves as a good example: if he needs something, he’ll get it. I’m not out to impress anybody with how I draw. That’s where my new step was most complete. Getting the painting to paint itself is magical. It’s not art in the sense of setting out to “make a work of art.” Picabia gave himself total freedom. He would paint the way he needed to, for what he was trying to do. So he really had no style; he had all styles. I once wrote that if Duchamp was the tortoise, Picabia was the hare.

AJ: The art scene has truly overflown its banks in the 1980s. How do you view what’s going on today?

WNC: When you think of it, there’s really nothing more hilarious than the so-called art scene. Selling a painting or buying one, for that matter, is a Surrealist act in itself. What prevents paintings from being considered commodities is the very fact that the prices paid for them never make any sense at all. That’s what I love about Mexico. Every Mexican Indian is an artist, and the motivation is not money. Art is a way of living your life, not a business. It’s too bad when kids come to New York and think they’re going to have some kind of “career” as an artist; they’re missing out on that whole other side, forgetting that the function of the whole thing is to liberate — they’re afraid to take that one step that will liberate them from the whole thing. And New York intimidates artists. They end up having no fun at all, and that is bound to affect the work. In a place like SoHo, the revolutionary is completely contained; as long as he is part of the scene, he’s not going anywhere — he’s not going to upset anything.

AJ: Artists in the ’80s must contend with abundantly seductive repression and the temptation of tacit self-censorship. Do you know of any cures for complacency?

WNC: You have to get completely away from things society imposes on you, to get down to satisfying your own curiosity. That’s what was so great about Andy Warhol: he was driven only by curiosity. He was too busy to buy himself a yacht or a Mercedes. He had to know everything, he had to know everybody else’s business. He was an artist for himself. And Warhol worked very hard at satisfying his curiosity. He was a very inspiring artist in that respect: There was absolutely nothing he wouldn’t try.

AJ: The true nephew of Duchamp.

WNC: Yes. He knew Duchamp well. Warhol would go over to visit at Duchamp’s a lot of times. I was there on a couple of occasions when Warhol dropped by. Warhol got a lot from Duchamp, and revered him as much as I did. And both were completely misunderstood. The media never really knew what to say about Duchamp, or about Warhol, and when they don’t know what to say they get cute. Very few people really understood what they were up to.

AJ: How do you interpret the message of Surrealism as an art movement?

WNC: Surrealism was more than a mere art movement. In fact Breton always preferred the poets over the painters. But it was much more. It was revolutionary — in the nastiest way conceivable. It was anarchistic. It put you way out on a limb and taught you how to cut the branch off behind you. Why does the artist feel obliged to con people into believing he’s respectable? What is this pretense of respectability? We really are dangerous. Our motives really are bad. If people knew what was going on inside our heads, we’d all be put in jail. Being an artist is the closest thing to being a criminal that exists.

AJ: Everyone knows that corporations prefer geometric abstraction, neo or otherwise, to bordello displays of unsavory nudes. Your exhibitions always seem to challenge the sanctimony of society as well as the art world itself.

WNC: It is a personal goal. Your bitch is with society; just think of all the nasty ideas you can get away with! And nobody reads them very carefully: they think it’s art. You can’t paint with the object of feeding yourself. If you do, it becomes something else, a career. Art is anti-career. It’s an anti-social experience.

AJ: You had already become acquainted with Duchamp before moving to Paris.

WNC: I got to know him in New York. Man Ray and I went there first, on our way to Paris from Los Angeles, and I saw quite a bit of Duchamp. Katherine Dreier was still alive, and he took me up to visit her in Milford, Connecticut. When I walked into her house and saw his painting Tu m’ (1918) on the wall, it hit me like a ton of bricks. This one painting, which is now at the Yale University Art Gallery, probably influenced me more than any other. The title implies “tu m’emmerdes.” What I get out of Tu m’ is that Duchamp is suggesting that the number of dimensions, planes of existence if you will, are infinite. He demonstrates this by using shadows, by using paint-sample cards, a painted tear, a real safety-pin — all associations of a cosmic sort, made to show that this goes on forever. Duchamp carried painting a little further into metaphysics. That painting changed the course of my life.

AJ: Roberto Matta also possesses this dimensional quality.

WNC: Matta claimed he got it from Diego Rivera. Rivera wanted to get as much into his educational murals as he could, so he developed this system of building these platforms in the space of his paintings, which Matta picked up and used in a much more interesting way.

AJ: How did Duchamp react to your work?

WNC: All he told me was, “You should continue painting.” He never talked much about his own work; he preferred to talk about other things. You had the feeling when you first met him that you’d known him all your life. He was so easygoing, you were not afraid to just talk. I had two great ambitions: one was to take Duchamp to a baseball game; the other was to take him to Las Vegas. I thought baseball would fascinate him because of the mix of skill and chance, but he had the game all figured out before the first half.

AJ: And Las Vegas?

WNC: We went there, and he got to play his system — the one he invented that wasn’t intended to win at roulette but only to break even. He had Walter Hopps carry the chips. Marcel would just tell him which numbers to put them on. They played all night long — and broke even.

AJ: How do you explain Duchamp’s secrecy, the outward appearance of almost total idleness behind which his last work was assembled?

WNC: He understood what a personal thing it was. Claiming he was no longer painting allowed him to buy time. Just as art doesn’t exist, neither does time. If there is one virtue I would like to corner the market on, it would be patience. That’s something an artist needs a lot of. Patience relieves you of all pressure, the pressure to do. Duchamp already had the reputation; if he had let it be known he was still working, everyone would have been trying to find out what he was up to. But nobody had any interest in what he was doing because nobody, including myself, knew he was doing anything. This gave him all the freedom in the world, for something like twenty years.

AJ: This year [1987], July 28 marked the one hundredth anniversary of Duchamp’s birth. How do you see his impact on our century?

WNC: If he had had his way, he would have let art out of Pandora’s box. He freed it, therefore he is for the moment rather unknown. I mean, collectors will pay to own anything he handled, but few make any attempt to really understand him. He remains too subversive. And he never let himself get cornered: witness the urinal. Duchamp had the kind of curiosity that is personally motivated, in and unto itself: I want to find out what this universe is all about because I’m going to be part of it pretty soon. That’s way ahead of religion.

AJ: Your foundation was instrumental in bringing Étant donnés to its home in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. How did you come to be among the first to learn of its existence?

WNC: One day he called me up and asked me to come to his studio downtown. I went, and when I came in, I was speechless. Here was a complete work of such complexity, which no one imagined even existed. But there it was. Since the Walter Arensberg collection was already in Philadelphia, he wanted Étant donnés to go there also. The next time I went back to his studio, the work had been crated. Duchamp said nothing. I think he knew that he was ready to die, that this was his last statement. Shortly after that, he went back to Paris and we never saw him again.

AJ: As you continue to paint, what do you see as the continuing influence of Surrealism?

WNC: They opened doors. And once those doors are open, they’re not easily closed again. They made things possible for each other. I think what they established was — let’s face it — there is no such thing as art.