“At least until the beginning of this century, there were always special relationships between certain cities.” Thus Diedrich Diederichsen poses the issue in his contribution to No Problem: Cologne/New York 1984-1989, the recently published catalogue to the exhibition last spring at David Zwirner, New York, sounding more or less certain that such creative inter-city special relationships belong to a past both recent and irretrievably lost, replaced, one presumes, by the diffusion and monotony of art fairs and jpegs. Nostalgia wafts through the book. It is captured by Diederichsen’s title, “Before Globalization,” and more pensively, if less succinctly, in certain passages from the second essay, by Bob Nickas, which finds him wistful, wonderstruck, and ruminating on the nature of history, of time itself: “Even as we bend the shape of time, eternity may be difficult to fathom. Having no beginning or end, there are only contours to be mapped. As an ongoing process of expansion and contraction, an overlay and succession that continually eludes fixed coordinates, our map is always in a state of unfolding.” Indeed.

Philosophizing aside, the texts straddle history and memoir, and the nostalgia is that of the participant observer, affecting not only critic and curator but dealer as well. “This exhibition is of personal significance to me,” Zwirner was quoted as saying in the show’s press release, “as I grew up in Cologne above my father’s gallery and was very much inspired by the creative and collaborative spirit of this particular generation of artists, gallerists, curators, and critics.” Each of the three — Zwirner, Nickas, and Diederichsen — searches these six years of re-materialization (to borrow a phrase from Nickas) both for what has been lost and for the faint beginnings of the conditions of art today.

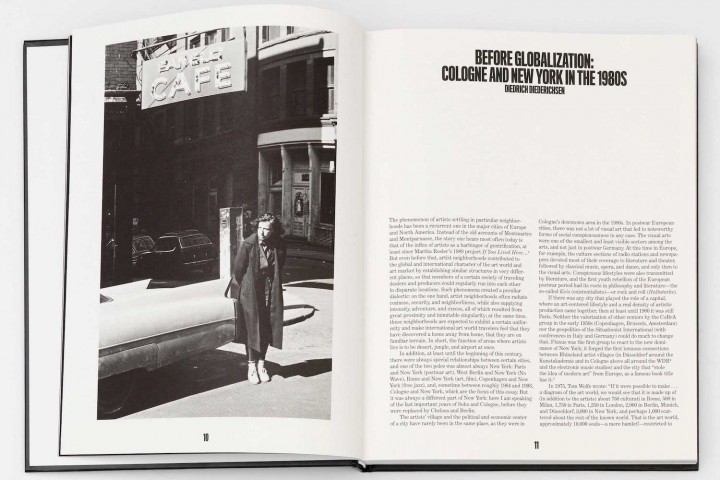

For Zwirner, writing in the forward, this is a story of institutions, markets and business models, of “a younger generation of gallerists” — Gisela Capitain, Max Hetzler, Monika Sprüth — who were “committed to their artists and realized that with an accelerating art market, productive career management demanded allegiances in New York” — Metro Pictures, Mary Boone, Barbara Gladstone — “point[ing] forward to the interconnected, global art world that is today taken for granted.” Diederichsen’s essay focuses on the shift in the center of gravity from Düsseldorf to Cologne at the beginning of the ’80s, the brief flourishing of the scene there — it’s preoccupations and parties — before things moved to Berlin by the mid-90s, and a bit on New York as seen from Cologne. For him, the key transformations of that decade, in Cologne as elsewhere, were, “the reconstruction or reintroduction of the artwork as a portable art-dealer-friendly object with a mimetic relationship to everyday culture and everyday life, and the spectacular presence of the artist as a component of the informal dimension of the art world.” Nickas, whose piece covers New York, is far less concerned with the specificities of place and periodization. Instead he provides a digressive appreciation and recollection of art in the ’80s — at times insightful, frequently rambling, and, in the final analysis, a morality tale in which that decade marked death rattle of significance in art, “perhaps the last period in which artists, critics, and curators, the exhibitions and the writing around art, led the way and were of consequence.”

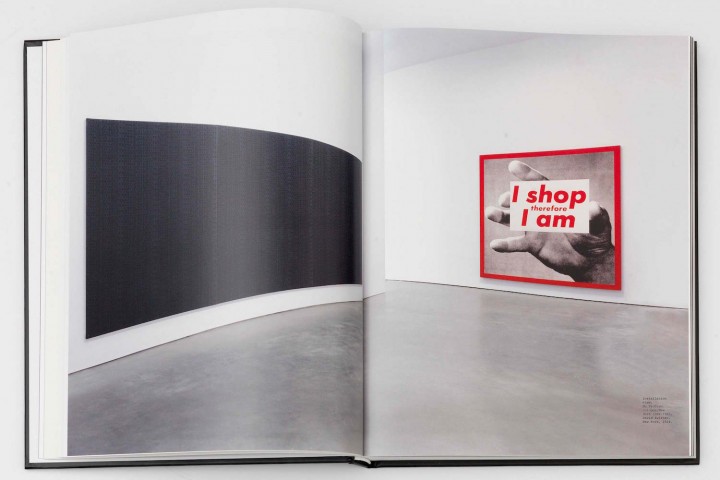

The book is predictably attractive, with crisp reproductions and installation photographs supplemented by grainy documentary images of the work as it was originally installed and reproduced ephemera. There are numerous pictures of artists hanging out and Kippenberger acting out. A museum quality exhibition that sprawled through three Zwirner addresses on 19th and 20th streets, much of the work is great and much of it familiar. The story they’re trying to tell — that of the “influences, affinities, and dialogues” between artists in these two cities, the special relationship — never really comes into focus. From the Germans we get almost exclusively paintings — many sloppy and sardonic — those of the Junge Wilde and the circle around Kippenberger: Walter Dahn, Jiří Georg Dokoupil, Werner Büttner and Albert Oehlen. One notable exception, Rosemarie Trockel, is unfortunately represented by only two pieces. The work out of New York, by contrast, is mostly cool, appropriative or rigorous, that of Pictures Generation artists and their immediate successors. The big New York exception, George Condo, did go to Cologne and seems to have felt a real sense of kinship with his equivalents there, but this hardly constitutes a special relationship worth building an exhibition around. Further muddying the waters, a quarter of the works in the show come from artists who did not live in either New York or Cologne — Mike Kelley, Raymond Pettibon, Fischli and Weiss and Franz West. Though they all exhibited in one or both of the cities between 1984-1989, such criteria verge on incoherence. I guess you had to be there.