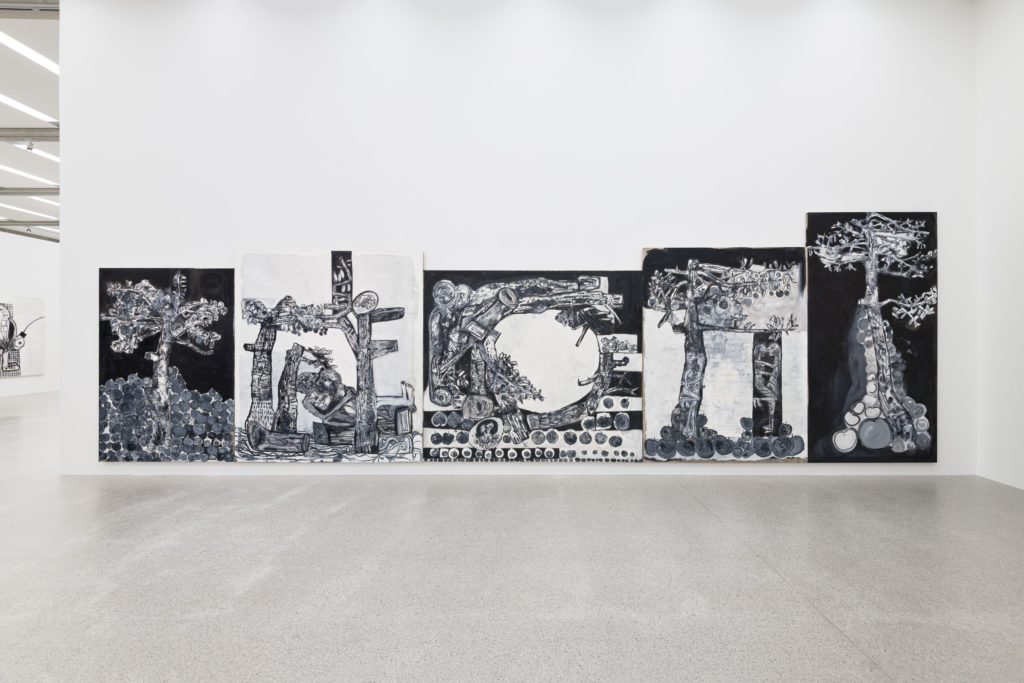

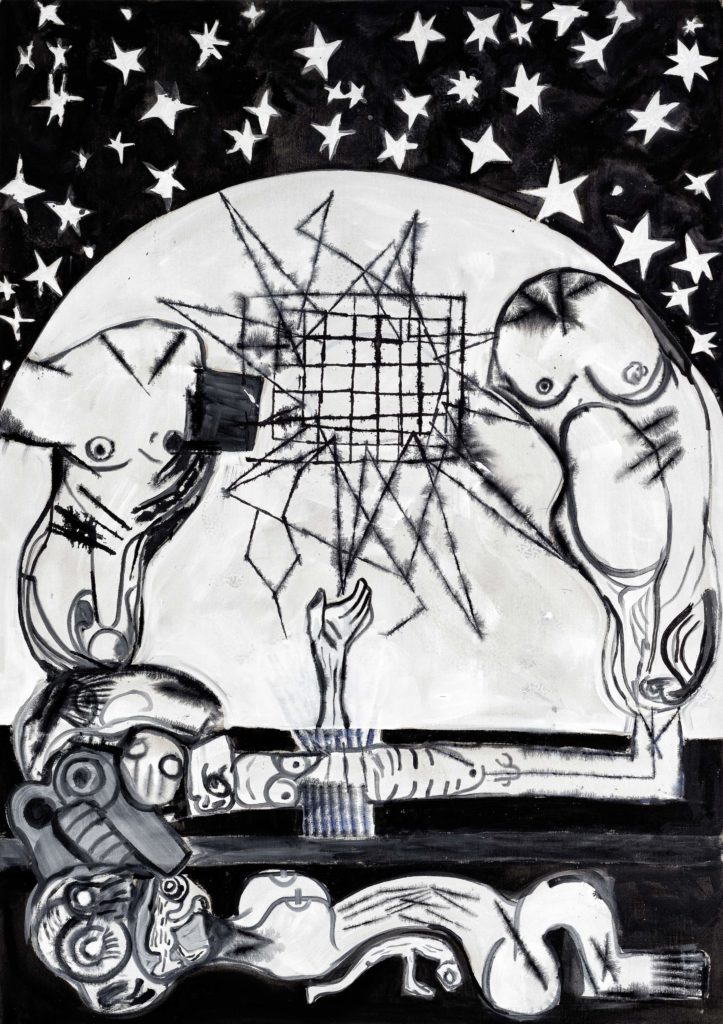

Tobias Pils’s ambitious exhibition “Shh” at mumok, Vienna, spans three spaces and looks back at a decade of his practice, building on his previous major institutional presentation at Secession in 2013. The show traces an evolution from abstraction to figuration, and from austere grays to a more expansive palette, though Pils himself seemingly resists treating such shifts as hierarchical or even particularly significant. He often returns to a small constellation of motifs — personal echoes threaded together with archetypes drawn from Western iconography: sacred family scenes, Christ-like figures, fractured bodies. What matters most, however, is not narrative but structure — a kind of excavation of pictorial language itself. In this sense, his work reminds me of the late Irish writer Manchán Magan’s idea of “capturing incidents of words that make us see the world in different ways.”[1] Like Magan’s lifelong exploration of how language shapes perception, Pils’s paintings seem to dwell in the fragile space where meaning frays and something more illusive steps in to speak.

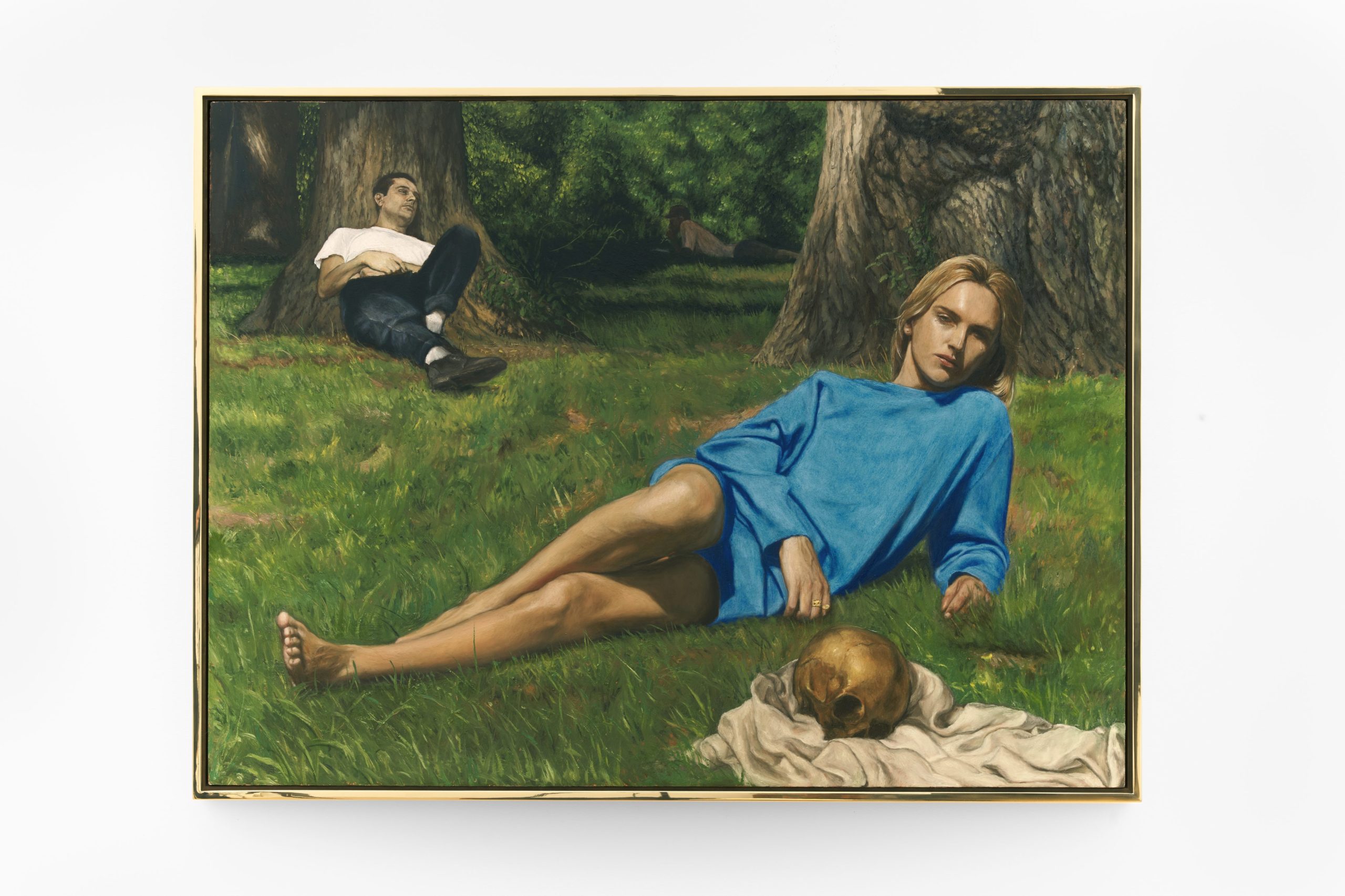

The title of the exhibition captures this openness with expansive economy. It is not a word in the strict sense, but an utterance — a sound that shapes atmosphere rather than describing it. Depending on context, it can calm or command, draw us closer or hold us apart, open a space or close it. It gestures toward a kind of communication rooted not in language but in breath, emotion, and the charged stillness between people — or perhaps as a warning of an unfolding threat. This invitation to hush runs throughout the exhibition. In Glas, Kerze, Bein (2025), Pils introduces grays, vibrant reds, and blues against a stark white background, framing a glass, a lit candle, and a wobbling leg — objects and partial subjects that seem at once fragile and monumental. Von Innen nach Außen (2025), a large still life, shows a kitchen table set with three glasses and a vase before a window opening onto a sparse winter landscape — beside the ghostly trace of an earlier, erased window. At first, the paintings suggest quietness, an inward turn. But the silence here is not neutral. A toppled cocktail flute interrupts the composition, hinting at aftermath — something has already happened, and we’ve arrived too late. Across the more recent works, this atmosphere of aftermath hardens into something darker. Soldiers, fractured figures, and scenes of implied violence begin to appear.

The first painting greeting visitors on the ground floor, Blindensturz (2024), is rendered in deep emerald tones against white. Three figures — resembling soldiers — are caught in the grip of an outstretched hand, as if directed by forces beyond them. It’s difficult not to read these works against the backdrop of current global conflicts, the endless stream of war images on our screens, and the silence that often accompanies them. What, then, is the invitation of “Shh” in this context? Is it a plea to quiet the violence, or a reflection of the suffocating silence that surrounds it — particularly within cultural institutions, including those in Austria, where political neutrality often masks complicity? This ambiguity is both the power and the risk of Pils’s work. The political charge is present, but it’s never pinned down. His canvases resist clear position, instead echoing existential traditions that run from Picasso and Alberto Giacometti to Georg Baselitz, with moments of domestic and intimate strangeness that recall Paula Rego. Titles like Happy Days (2023), oscillate between nostalgia and absurdity. On one level, they might reference an imagined childhood, a time perhaps before mediated violence; on another, they nod toward Samuel Beckett’s play of the same title, where optimism teeters on all-out despair. In Pils’s Happy Days, a triptych, distorted figures blend with earth, their bodies warped and indistinct. His vision is more oblique, more withheld, yet no less unsettling.

Susan Sontag offers a way into this tension. In Regarding the Pain of Others, she writes: “The appetite for pictures showing bodies in pain is as keen, almost, as the desire for ones that show bodies naked.”[2] She asks what such images produce — sympathy, distance, paralysis? Ambiguity in representation, she suggests, does not neutralize politics; it can deepen the need to ask what is being asked of us as viewers. Pils’s refusal to dictate a position forces precisely that: a reckoning with the uncertain space between witnessing and looking away and then, perhaps, looking again. That uncertainty can feel unsettling, even dangerous. In a moment saturated with images of violence — many of them censored, downplayed, or politically instrumentalized — the space of ambiguity becomes fraught. Is “Shh” an appeal for silence or an indictment of it? Is the viewer being calmed or implicated? Pils does not answer. Instead, his paintings hold open a space where the question itself can reverberate.

[1] Manchán Magan, “Our perception of the world can change when we see things through the Irish language,” The Journal, November 20, 2021.

[2] Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), 41.