Much recent critical theory has been concerned with the following proposition: that although the triumph of reason claims to have unearthed all our bodily secrets via the meticulous imaging of our external and internal mechanisms, the body — site of contact, fragility, and erotic possibility — still holds transformative mystery. To this end, SculptureCenter’s ambitious, site-responsive group show “to ignite our skin,” curated by Jovanna Venegas, makes a compelling case for returning to the fleshly body, even amid postindustrial disembodiment.

On the door to the courtyard and south-facing windows, Sofía Sinibaldi’s membrane-like imprints (all made in 2025) visualize the epistemological and ontological impurities and instability of photographic processes and apparatuses. Layering casual snapshots with flatbed scans of familiar surfaces, Sinibaldi creates synthesized composites that depart from the context of capturing her daily commutes in New York City and arrive at affectively heightened abstraction. These artificial images are then printed on tissue papers, producing zones of marks full of tears, creases, aged impressions, fuzzy suggestions, leakages, overflows, and scrapes. The result has a painterly quality. Her images blur into one another, frustrating any search for pattern. Still, parts of these works evoke surveilling eyes or spattered bodily fluid, alluding to the intensely embodied nature of photography.

Ana Raylander Mártis dos Anjos’s Trinity (2025) forms a charged set of relations with SculptureCenter’s architecture as well. Used clothing items collected by the artist, tightly wrapped and knotted around poles, become uncanny stand-ins for Brazilian bodies, condensing individual histories in and through different scales and potencies. One part of Trinity, like a household tool, leans against the wall next to the information desk. Basket and hoses next to it firmly declare a second life for the repurposed clothing, in a suspended fantasy of utility. In the middle of the gallery space, several other similarly produced column-like objects congregate. A few collapse on the floor, awaiting activation. Others, notably more colorful, closer to the skin color of everyday Brazilians, initiate a towering, triadic altar, or scenography of primordial animism that connects earth to sky — or, in this case, SculptureCenter’s ceiling beams. A parable for brown commons, Trinity speaks to the power of the masses; even their remnants contain spiritual prowess.

Elsewhere, Erik Tlaseca’s folding screen series “Espejos (Mirrors)” (2025) depicts six almost-identical figures that take formal cues from Mesoamerican witch paper cutting. The figures, silhouettes of similar sizes, largely made from animal skin and fur, possibly cite cultural imaginaries surrounding the archetype of wild humanoid entities that fall outside the sphere of culture. One exception is the figure cut from a leather motorcycle suit, a sign of modern society. Perhaps, as the title suggests, the act of mirroring — a spatial and psychical technique that manipulates distance between physical and temporal markers — provides clues here. The six figures, on a spectrum that does not necessarily form a continuum, give a frame of reference for how traces of subjectivity are constantly made anew, channeling ranges of history and culture. In a similar vein, Umico Niwa’s Metropolis Series: Loving the Vagabond (2025), a sprawling, centerless apparatus of foraged bamboo, twigs, and other plant matter, considers a nomadic approach to time and memory. Now-lifeless seeds and fruits gathered from Houston and San Juan trigger distant, faint associations. Additional seeds tucked into the dents of SculptureCenter’s brick walls further disturb the supposed aesthetic neutrality of the exhibition space.

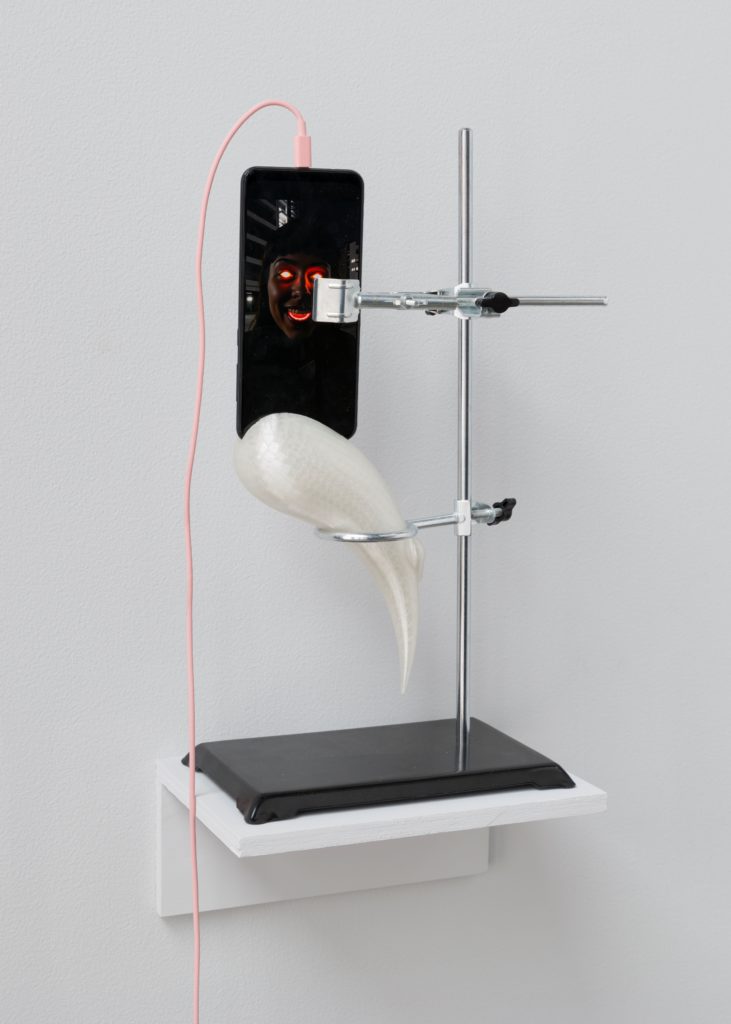

Sarah Friend’s six new “Prompt Baby” iterations (all works 2025), following Andrea Fraser’s thinking on libidinal entanglements among artists, collectors, and market value, produce far more dramatic and aroused public parodies on relations of exchange. In each “Prompt Baby,” pornographic prompts, given by collectors of Friend’s NFTs, play on a phone screen, followed by AI-generated images of such prompts using Friend’s avatar. The images elicit desire, disgust, or horror to different audiences. In Prompt Baby (cage), erotic images literally play in a cage, a reminder that the work is situated by networks of private wealth increasingly desensitized to sex and violence, chasing new stimulations. A reminder that the fleshly body simultaneously invites and births transgression, liberatory practices, and subjugation to and by power, all manifested on the surface of our skin.