Paul McCarthy’s art often challenges societal norms and expectations through absurd, provocative, and humorous imagery. Even his most disturbing works — such as Cultural Gothic (1992–93), a sculpture depicting a goat being sodomized by a young boy with his father standing behind him, encouraging him to continue, or The Garden (1991–92), a full-scale staged environment featuring an older man “humping” a tree and a young man humping the ground — are infused with a strange sense of humor. Such grotesque comedy shifts the viewer’s perception from disgust to uncomfortable fascination.

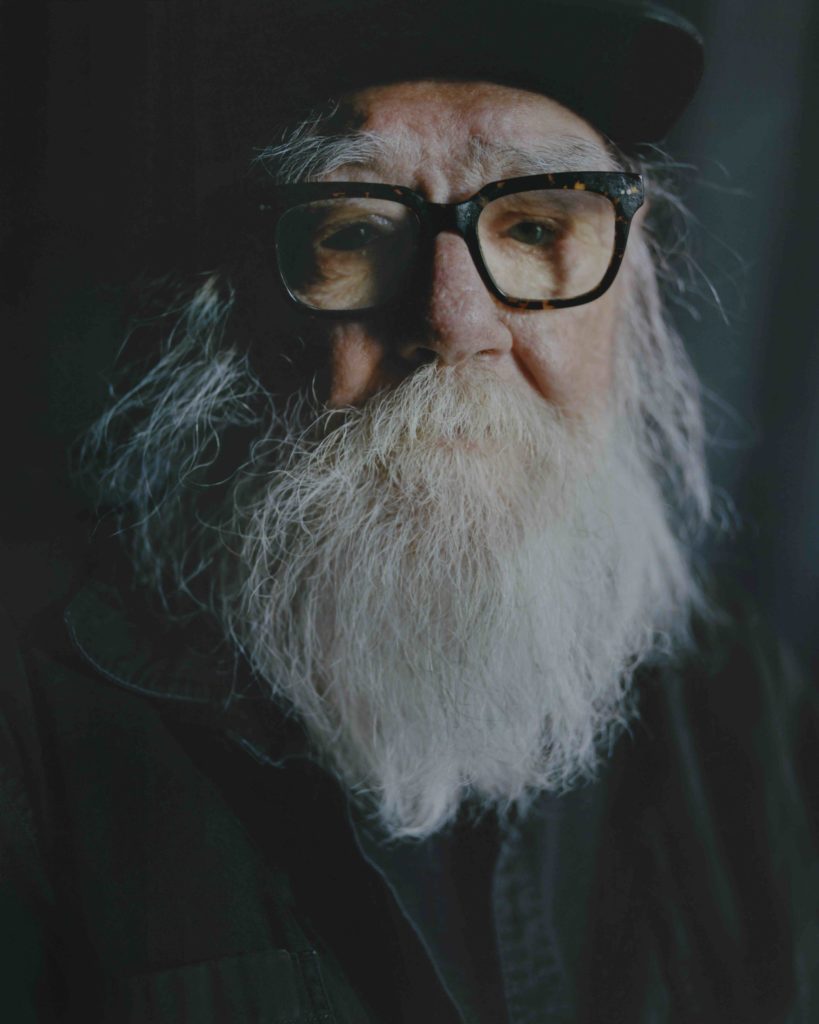

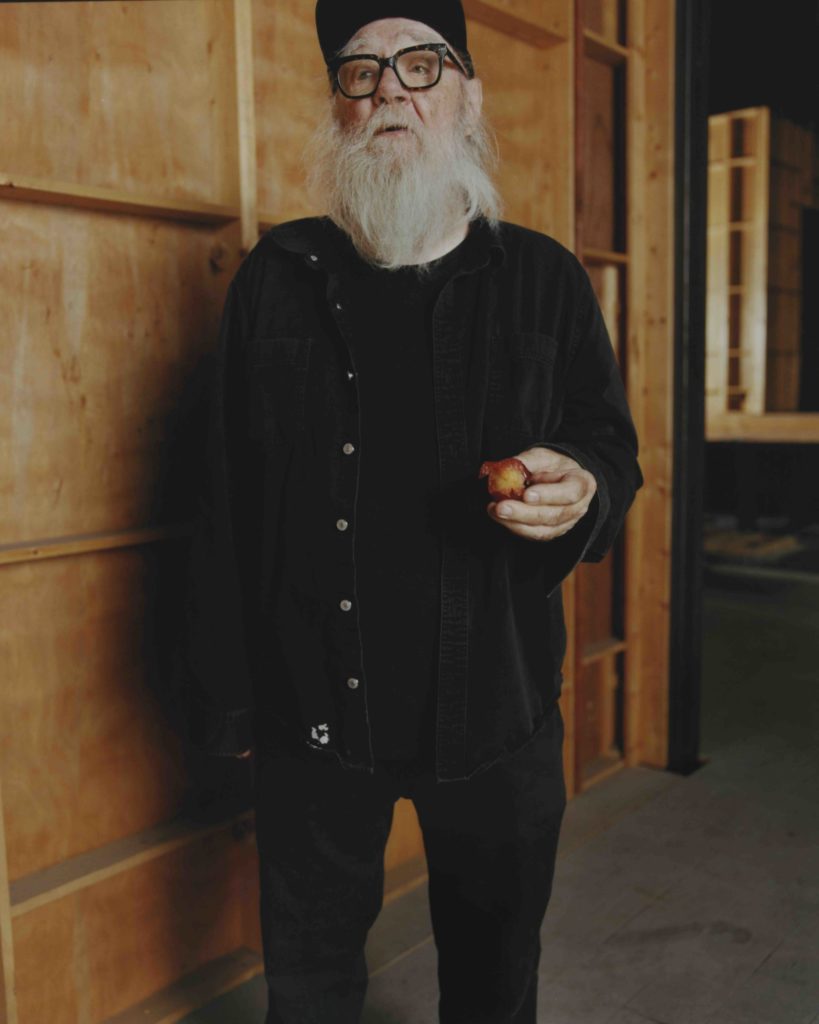

McCarthy’s practice reveals how humor can disarm, confuse, and ultimately deepen the viewer’s emotional engagement. When you speak with him everything sounds so plausible. The way he casually addresses highly complex dysfunctional family relationships or societal issues is consistent with how art can hit that very soft spot inside of us. I once sat at dinner with him in London, as he and his son Damon were concocting the film Piccadilly Circus (2003). At some point, McCarthy wondered aloud, “What if George W. Bush was a painter in the film? Could he paint with his ass?” He asked this with the most sincere and spontaneous tone, which made made the whole table agree that the proposed role could be completely normal — or silly normal.

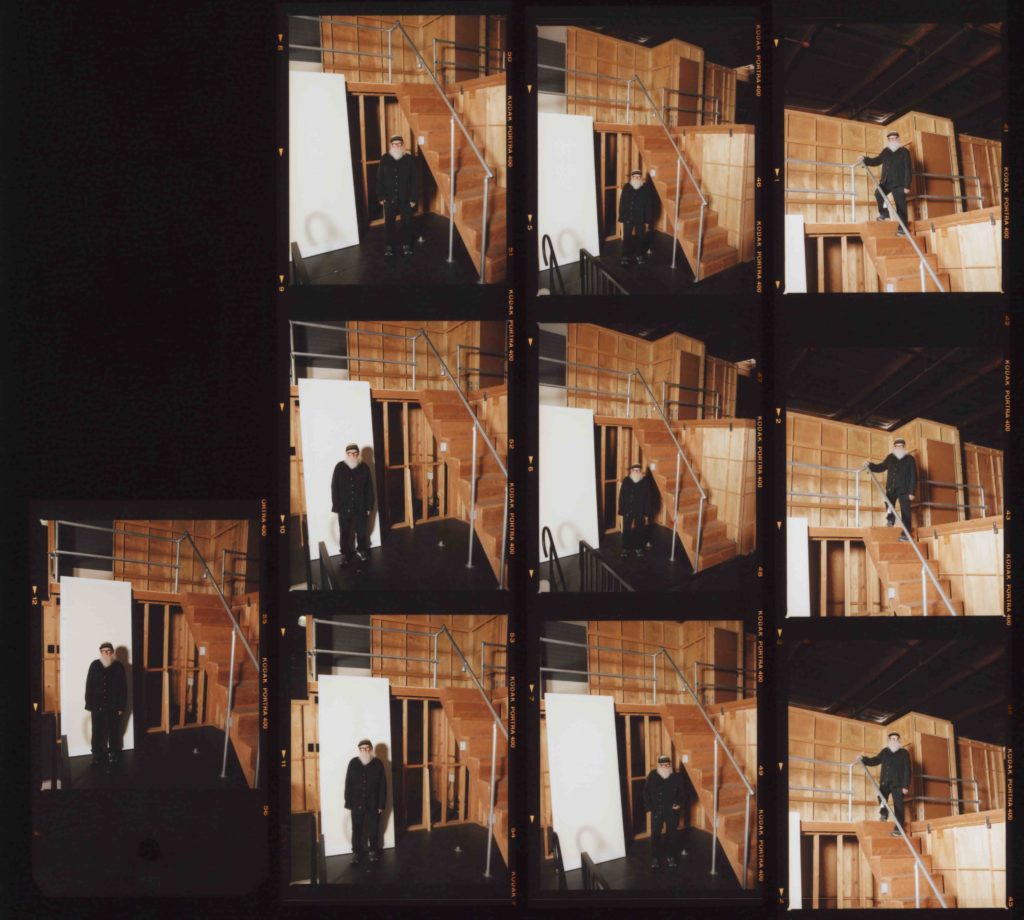

For Piccadilly Circus (2003), Hauser & Wirth’s inaugural show in London, a former NatWest bank, only lightly restored, functioned as the stage set for McCarthy’s shoot. The film starred a president (George W. Bush), multiple Queen Mums, and a terrorist (Osama bin Laden), all cast in a post-Pasolinian fever dream. The film evolved into a grotesque tea-party-turned-orgy, a collapse of political theater into a free-for-all. I was working as an intern on that project, and I got to restock the scene with HP sauce, ketchup, and doughnuts the whole time they were filming.

While McCarthy’s approach may have initially been read in terms of its refreshing playfulness, it has evolved toward a more nihilistic and abject aesthetic. Yet his use of humor and his complex layering of images and meaning still deeply affects the viewer, taking them on an emotional ride. This is what differentiates his work from mere sadomasochistic exhibitionism. The violent, cartoonish acts he portrays cannot be dismissed as sensationalism.

One of McCarthy’s most well-known works, Complex Pile (2007), is a monumental inflatable sculpture resembling a giant pile of excrement. The work’s enormous size and indelicate subject matter has generated significant public reaction and debate. It is often read as a critique of consumerism, excess, and the art world itself.

Throughout his career, McCarthy has maintained a sharp and straightforward communication style. Whether collaborating with artists like Mike Kelley or his son Damon, or actors like Lilith Stangenberg, this directness is reflected in the honesty and transparency of his large-scale installations, videos, and performances, which leave little to the imagination.

Around the early 2000s, McCarthy’s monumental artistic practice entered the realm of public art with Santa Claus (2002), a controversial sculpture nicknamed the “Butt Plug Gnome” that was exhibited in various squares and institutional courtyards (e.g., the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam). Also notable in this period was Train, Mechanical (2003–10), a large-scale kinetic sculpture of George W. Bush and pigs. The large-scale installation has become a typology of the artist’s practice.

The “White Snow” series (2008–15) presents a twisted take on the Snow White fairy tale. The work culminated — more or less — in a sprawling 2013 Park Avenue Armory installation titled WS, making it one of McCarthy’s largest and most ambitious works to date. A dark, adult-themed reimagining of the Snow White narrative, the piece blends elements of the Disney film with McCarthy’s signature unfiltered style. He built a replica of his childhood home, nestled it in a plastic-fantastic forest and a barrage of video projections. It features thirty-five hours of performance art projected onto the walls — a cacophony of imagery.

The “White Snow” piece included large sculptures, installation, video projections, and a four-channel, seven-hour video of four separate edits synced to one another, playing on a 30-by-160-foot screen at each end of the building. The work featured explicit content and was restricted to viewers over seventeen, sparking debates about censorship and the boundaries of art.

Through its distortion of a beloved fairy tale and Disney character, the work offered a harsh critique of American popular culture and consumerism. Visitors could walk through the forest and voyeuristically peer into the windows of the house, participating in an immersive and dystopian experience.

The installation received mixed reviews, with some praising its ambition and others criticizing its excess and explicit content.

WS further cemented McCarthy’s reputation as a provocateur and pushed the boundaries of what could be displayed in a major art institution. WS isn’t mirroring excess; it’s weaponizing it. It’s a neutron bomb of sensory overload, designed to short-circuit our synapses and leave us twitching in a puddle of our own preconceptions.

It’s not just pushing boundaries — it’s napalming them, then dancing in the ashes of our comfortable little art-appreciation paradigms. In a world where we’ve seen it all, McCarthy manages to create something that actually makes us feel again — even if that feeling is mostly confusion and mild nausea.

Now, it might make sense (or not) to define different periods of Paul McCarthy’s practice.

McCarthy’s early performance art, between 1970 and 1983, was characterized by his exploration of identity, particularly through skewed characters, parodies of authority figures, and dysfunctional family relationships. His performances, often visceral and humorous, delve into themes of popular culture, consumerism, and the underbelly of the American Dream. He utilized a range of materials and often incorporated body painting, oversized props, and elements of spectacle to challenge viewers’ expectations and provoke analysis of fundamental beliefs.

Performance has remained a constant part of the artist’s practice — a practice that has evolved through distinct phases over the course of his life. We can broadly identify several key stages in the development of his approach and thematic focus:

Early performative works (1960s–1970s):

In the early stages of his career, McCarthy established himself as a pioneer of performance art, often using his own body and unconventional materials like bodily fluids and food to challenge societal norms and push the boundaries of acceptable artistic expression. Works from this period, such as Sailor’s Meat (Sailor’s Delight) and Tubbing (1975), laid the foundation for his subversive and confrontational practice.

Installation and sculpture (1980s–1990s):

As McCarthy’s practice expanded, he began to incorporate installation and sculpture, creating environments that immersed the viewer in his twisted reinterpretations of American culture and mythology. Pieces like Family Tyranny/Cultural Soup (1987), Bossy Burger (1991), and The Garden (1991–92) showcased his ability to translate his performative sensibilities into large- scale, immersive architectural works.

Exploration of popular culture and iconography (1990s–2000s):

During this phase, McCarthy’s work became increasingly focused on deconstructing and reimagining iconic figures and narratives from American popular culture. He used characters such as Santa Claus, Snow White, and political leaders to expose the underlying anxieties and contradictions within these cultural touchstones in works like Santa Chocolate Shop (1997), Caribbean Pirates (2001–05), and the “White Snow” series (2008–15).

Performance-video hybrids, edited as features and episodes in series (2014–present):

Over the last decade, McCarthy has been involved in the production of four major performance-video series. The first, CSSC, is an initialism of “Coach Stage, Stage Coach” (2014–ongoing), consisting of four feature-length episodes. In 2016 McCarthy began DADDA, an acronym for “Donald and Daisy Duck Adventure,” consisting of between ten and fifteen episodes/ features. DADDA grew out of CSSC. The projects are sociopolitical satire using the thematic clichés and settings of the Western film genre, and the characters in each are a cast of celebrity look-alikes that partake in violent behavior. The pieces were written by Paul McCarthy and directed by both Paul and Damon McCarthy. Paul McCarthy plays Ronald Raygun in CSSC and Donald Duck in DADDA. In 2019, McCarthy began NV, an acronym for “Night Vater.” The piece is an abstraction, a reinterpretation of The Night Porter, the 1974 film directed by Liliana Cavani. NV takes place in Los Angeles and is the story of Lucia, a young German actress, played by Lilith Stangenberg, who comes to LA and is consumed by her relationship with Max, a film producer, played by McCarthy. NV is a nineteen-episode series, from which came A&E, an initialism for “Adolf and Eva” and “Adam and Eve.” The ten episodes of A&E will not be narratively connected to each other aside from solely including the two main characters, Adolf Adam and Eva Eve, played by McCarthy and Stangenberg. The episodes focus on the sexually violent love affair of two buffoons. McCarthy wrote the scripts as a sort of skeleton for improvisation. All four projects are ongoing, with new episodes and features still to be released.

Collaborative works:

Throughout his career, McCarthy has frequently collaborated with other artists, most notably Mike Kelley, Jason Rhoades, and Mike Bouchet, and he has collaborated and worked with his son, Damon McCarthy, since the Piccadilly Circus piece in 2003. Since 2019, McCarthy has done more than seventy performances with Lilith Stangenberg. These collaborative works have further expanded the scope and complexity of his artistic practice, allowing for the synthesis of diverse perspectives and approaches.

Drawings and paintings:

McCarthy has also produced a significant body of drawings and paintings, often related to his sculptural, installational, and performative work, further exploring his key themes. McCarthy’s work continues to evolve, with his recent focus on the CSSC/DADDA and NV/A&E series.

Across these evolving stages, McCarthy’s artistic vision has remained centered on a relentless interrogation of American culture, mythology, and the human condition. His work has consistently pushed the boundaries of what art can be, challenging viewers to confront their own preconceptions and biases. The work of Paul McCarthy does more than simply hold a mirror to cultural excess — it invites us to reconsider the very frameworks through which we understand and interpret our world. Its true significance lies not in its shock value, but in its capacity to dismantle our comfortable modes of perception, urging us toward a less distanced engagement with art and cultural critique.