Fanta Sylla: Ever since the publication of Maggie Nelson’s The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning in 2011, I have yearned for an investigation into what would be the antonym of cruelty — goodness, care, kindness — similarly pointing to examples in the arts. I am also thinking about Toni Morrison’s questioning of a certain complacency toward evil and the silencing of goodness in literature. “Give It or Leave it” seems to be constructed around legacies, figures, and spaces that reflect those underscrutinized values. Is this something you have been thinking about in conceiving this exhibition? How to carry goodness or care into an artistic space?

Cauleen Smith: Ah! Maggie Nelson’s book is on a long list of things I must read, but I confess to not having read it. However, the ideas she offers in that book are well in play in so many discourses around art that interest and influence me. However, Toni Morrison’s simultaneous boredom with evil and interest in a kind of emphatic cowardice and Americans’ equivalency with goodness and weakness is an idea I inhabit with more familiarity. I had an experience on a film shoot that really made me think about the way that cultural production can so easily reify the violence in our world. In 2010 we shot Remote Viewing. It is basically a reenactment of an individual’s memory in which as a child he watched the one-room schoolhouse he attended be buried underground. At the time I’d never heard of burying structures, though I’ve since learned that it’s a common (though incredibly bizarre) way of getting rid of an unwanted structure. I hired a crew to build a one-room schoolhouse and I hired an excavator to dig a gigantic hole in which to bury the house. All of the tension building up to the moment of tipping the house into the hole was exhilarating. But then, the moment that structure tipped over and vanished into a gulf of noise and dust, we were all wounded, particularly my art director who so lovingly built the thing. This reenactment had done little more than reinscribe the trauma that I wanted to protest. And I kind of decided after that that I try not to make things that reenact the violence we experience in this world. There are other ways of dealing with trauma that don’t involve subjecting others to the pains we carry. I’m looking for those methods.

So “Give It or Leave It” is just as you say, constructed around individuals, collectives, spaces, and places that reflect radical forms of generosity and visionary ideas around sociality and living and producing culture. But “goodness” — that’s a tricky word. A word too easily reduced to piety. And I am not interested in piety at all. I’m actually just interested in the wondrously inventive ways that people survive trauma without subjecting those around them to its reenactment. Simon Rodia, Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda, the Combahee River Collective — wow! Instead of making people see their pain or loss, they offer people something they want to see in the world, something that heals and sustains them, in the hopes that it will do the same for others. I mean, just play some Alice Coltrane recordings and describe how it works on you! And frankly, as corny as it sounds, this is what interests me about making art. The work attracts interest and conversations based on what it offers, what it does. And it surely repels in the same way. Ha!

FS: There are various components in this exhibition, from video work to a site-specific installation to sculptural work, that refer to artists such as Alice Coltrane or Noah Purifoy, among others. How did you envision the connections between these artists?

CS: This entire body of work sprang out of a repetition of a form that I noticed between two very unlikely sources. I’ve been obsessed with Shaker drawings for over a decade. It started with finding France Morin’s catalogue on the subject — still the best writing you can find on these drawings — and then just sitting with this question for a long time. How is it possible that in the middle of the nineteenth century a religious cult that eschews all visual culture, all decorative impulses, would turn to these mysterious things they called “gift drawings” to galvanize and sustain their community? I find this move toward visual culture significant and crucial. Moreover, most of the drawings were made by young women. They would receive a “gift” from an ancestral presence, maybe Mother Ann Lee, but also maybe an African ancestor (really!) and then they would record the vision in the form of a drawing and give it to the designated receiver. These drawings mix so many ways of image-making, from embroidery samplers and quilting to German Fraktur drawing and Masonic symbols. Embedded in the designs of several major works are these mysterious objects — they look like machines, but also like, say, a sewing machine, a tablecloth, and a fruit tree grafted together. These crazy little objects were frequently labeled as “heavenly musical instruments.”

So then years later I start getting very into Alice Coltrane. I visit her ashram in Malibu. I buy everything I can afford from their little bookstore, most notably a tiny book called Monument Eternal. In this book, Turiyasangitananda describes the “austerities” that she performed while becoming a godhead. Really harrowing tests she put her mind and body through; she also left her body and explored the astral planes. She describes that in one of the astral planes you will find instruments that play themselves. Instruments that require no handler, just pure thought and intention. Now, when young girls in upstate New York in the middle of the nineteenth century and Alice Coltrane are describing the same thing, one has to pay attention, right? So a deep dive into Shaker communities led me to Sister Rebecca Jackson, a black woman who joined the Shakers because she responded strongly to the ethics of their spiritual practice. And then there was this unpublished photograph from 1968 taken by Life-Time photographer Billy Ray of a group of young men hanging out inside of the Watts Towers a couple of years after the riots erupted. I was transfixed by how gorgeous these young men were and how profoundly their easy, relaxed, and dare I say elegant stances contradicted the photographer’s initial agenda, which was to capture the simmering rage of black youth. And this picture was also a document of the Watts Towers before they were fenced and gated, thereby making public access strictly supervised. So, the Shakers were known for taking in all strays; they repopulated by taking in orphans and unwanted children. Alice Coltrane built her community around Vedic religious practices and music, drawing black folk who were into Eastern philosophy from all over the country to her land in Malibu. And Simon Rodia’s towers have always functioned as a beating artery of agency and advocacy for a community that the powers that be of Los Angeles would be happy to ignore under other circumstances. Then of course Noah Purifoy, along with many other artists, developed a way of making sculpture and building community culture that emerged from the ashes of the Watts Riots, making art from detritus and making a space for others to make art as well. I was just recognizing patterns of radical generosity and patterns of visionary certitude that manifested itself as actual places (Watts Towers, Sai Anantam Ashram, Rebecca Jackson’s Philadelphia Shaker house) and things (gift drawings, sculptures, thrown away things, radios, and sunlight).

FS: How do you approach the archive and its integration in your own work? It seems there is always a concern about ethics in your work.

CS: Even though I’m a filmmaker, I have a profound resistance to representation of the figure, so I get way more excited about a canceled check from Sun Ra to Marshall Allen’s mom than I do of a photograph of him performing. I get way more excited about noticing that Octavia Butler has three different kinds of handwriting — depending on whether she is at her desk, on the bus, or waiting for the bus — than I do of a picture of her at a book signing. So for me the archive is about all the things that cannot be replicated and rendered, about interiority instead of about representation. I don’t think I hold myself to very high ethical standards when it comes to archives. I go into archives to answer my own questions or find new questions to ask. I’m not really looking for facts; I’m just looking for questions and possibilities and suggestions of the possible or models for ways of making. Particularly with artist archives, I’m just there to learn from them. Octavia Butler’s rigor, discipline, struggle, humility, empathy, love. Sun Ra’s deep study of language, theologies, sound as form, synesthesia. I’m just learning from them.

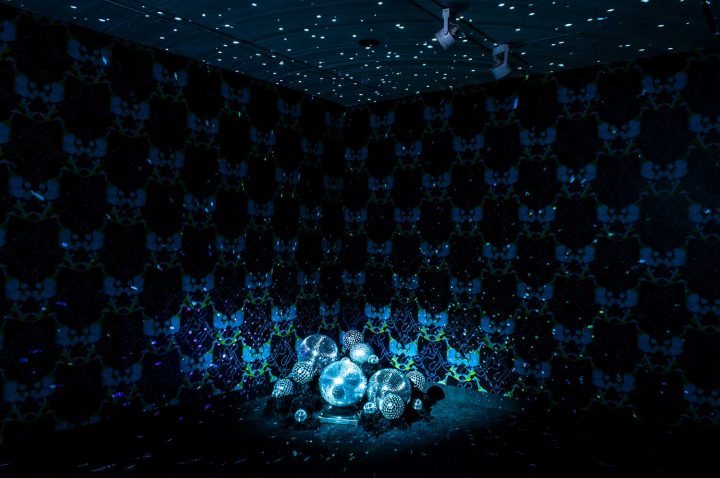

That being said, I do make distinctions between appropriating and recontextualizing and theft. I try not to steal. To me the definition of stealing is the burying of one’s source: the untethering of a source material from its author; the inhabiting of an idea that one lifted fully developed from another maker without acknowledging the homage. I find little utility in that. “Give It or Leave It” was not a terribly archive-dependent show. In fact, the main archive in the show is totally present in Epistrophe (2018) — a big green velvet table cluttered with objects. That is an archive of associations, travels, affections, desires, questions, and longings posted from a particular perspective (black woman) directed in a particular direction (black futures<>human futures). Those objects are a consolidation of a personal narrative that attempts to insert itself into larger histories and endless cartographies. The videos playing on flat-screen monitors (which become the landscapes projected on the wall) are also a personal archive of thirty iPhone videos and YouTube downloads from NASA and National Geographic. These videos constitute my journal. I didn’t really think about it in that way until presented with this wonderful question — but “Give It or Leave It” is actually a personal archive presented for public use and contemplation! But I do a lot of quoting and citing. One of the first images you see is the Billy Ray photograph that allowed me to consider the potential for radical generosity in Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers. Then of course there is the wallpaper (Space Station Chinoiserie #1: Take Hold of the Clouds, 2018), which functions as a site-portal and as an archive of the crucial sites that inform the entire show: Watts Towers, Turiya’s Ashram, the Combahee Rover Battle fought and won by Harriet Tubman, and Noah Purifoy’s desert museum. Initially, the 16-mm imagery that appears in both Pilgrim (2017) and Sojourner (2018) was stuff I shot just as research — just using my Canon Scoopic home-movie camera as a way of observing, of seeing sites that I visited through the lens, to understand their cinematic potential. I was using the camera to see as a form of research as opposed to journaling. So in a way that is also an archive. The last image of the film Sojourner is a reenactment of the first image you see in the show: Billy Ray’s Watts Tower portrait of the young men. The banners are also artifacts based on discovery. “I appreciate you in advance” is a term one hears a lot in Chicago from elders to youngsters. And “afflict the comfortable, comfort the afflicted” is lifted directly from Paul Thek, one of the patron saints of this body of work, as was the style of the banner.

And then there are the three ikebana movies. I just keep making them. Contemplating the human relationship to flora, our need to burden flowers with symbolic meaning and then control their bearing is some kind of weird meditative practice for me. I’d never shown any of them together before “Give It or Leave It.” I think sharing them as a collection makes them legible as an ongoing practice, a collection, and because I see no end to making the ikebana videos, inevitably as an archive that contemplates how comically rigid and awkward we humans are in our consideration of “the natural.”

Maybe all of the work I have done in archives has turned me inside out! And now in this show, I am not just offering up discrete objects but a constellation of gathered thought and practice for the spectator.

FS: How does “Give It or Leave It” build upon “The Warplands,” your 2017 exhibition at the University Art Galleries at University of California, Irvine? Both include Pilgrim (2017), the short video centering Alice Coltrane. What kind of space were you trying to produce with “The Warplands”?

CS: The first conversations I had with Rhea Anastas, the curator and instigator of “Warplands,” were so wonderful because we didn’t really talk about what I might make; we just talked about what we were reading and what we were worried about in the world. I was still living in Chicago but spending a lot of time in L.A. doing the Octavia Butler research as well as trying to create a relationship with folks at the Watts Towers Art Center. And what Rhea is really good at is recognizing the coherent threads running through things that most might say were quite disparate. So as I’m developing the work that ultimately becomes “Give It or Leave It,” Rhea sits with me and observes that I have a pile of work accumulating in my studio that is all speaking to a particular love and care of place.

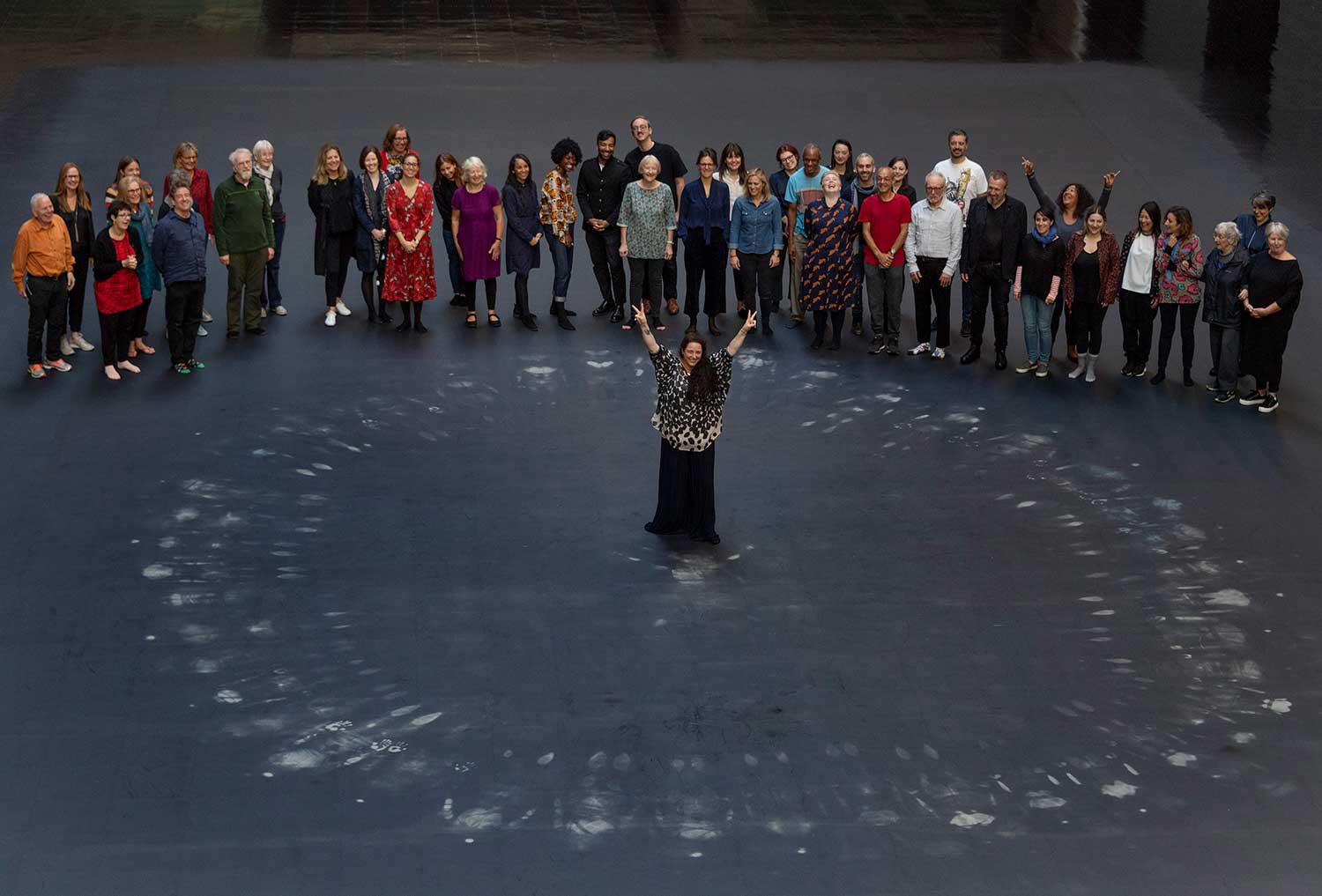

Gwendolyn Brooks is not a figure that I foreground in “Give It or Leave It,” but she is the presiding influence over everything in “Warplands.” “Warplands” is austere, disciplined, and solemn. It’s a show about the ways that life is recuperated and buttressed without much support, and when no one is looking. Lessons in Semaphore (2016) enacts love of place, love of humanity in the most absurd and gentle way, I think. The Conduct Your Blooming banners (2016) were also a gesture of love and care, labored over privately in my living room but then displayed defiantly in our neighborhood as a way of contributing to the visual culture that we live in with our neighbors. The Human 3.0 Reading List (2015–16) is my attempt to gently mentor young activists in Chicago who are fighting for the right to just live without fear of gun violence ending them prematurely. But the show resolves in the bright illumination of the film Pilgrim. And so then Pilgrim is what begins the journey through “Give It or Leave It.” We pick up where I left off, so to speak. “Give It or Leave It” is a very forceful and unfettered expression of my desire for a nonexploitative way to live, work, make, and move through the world. There’s the wallpaper that chronicles microsites like obscure Shaker villages and desert art outposts, and the epic scale and awe that is planet earth orbiting our star. I was texting Rhea about the piece overhead in the large gallery, Sky Learns Sky (2018). The colored gels on the skylights above kindly darken the room so that video is visible, but they also make the light from the sun visible as well in the form of color washes and streaks that move across a large wall. I was telling Rhea that Sky Learns Sky was incredibly exciting, if only I could just figure out how to get people to slow down long enough to watch it! Ha! “Give It or Leave It” speaks directly to and about instances in which radical generosity succeeded in producing sustenance and shelter for all those who participated in producing the space. And when I say producing the space, I mean something as simple as being present and spending time. “Warplands” was a journey through practices and tactics, I think. I hope people moved through that show feeling as if they can make the world they want. “Give It or Leave It” ruminates on the same ideas but insists on speculating about future practice, use and participation, social organization. Spectators are invited to kick it in an indigo-dyed lawn chair, contemplate flower arrangements, watch the earth rotate, dream of an epic love, and love your friends, love your family, give it all away, and create the world with what is left behind.