Oh heart, oh heart, blind like daylight

— Dionne Brand [1]

[1] Dionne Brand, Ossuaries (McClelland & Stewart, 2010), 34.

I talk to Anastasia Pavlou in front of the sea — on the Bay of Poets (Golfo dei Poeti), to be exact, along the Ligurian coast between Lerici and San Terenzo. I have come to commemorate the death of the young poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who was engulfed by the waves of the bay on July 8, 1822, exactly two hundred and three years ago. I have come to encounter a threshold. I have come to write. I have come to deal with misaligned hearts. Pavlou has never been here and is not too familiar with the Shelleys and their unconventional lives, but she too carries spectral companions in her work and life. Books, citations, dead writers, photographs of friends, dry flowers, Virginia, Agnes, are waves that live in her studio and in her paintings like a constant undercurrent, like a quiet storm about to release lightning.

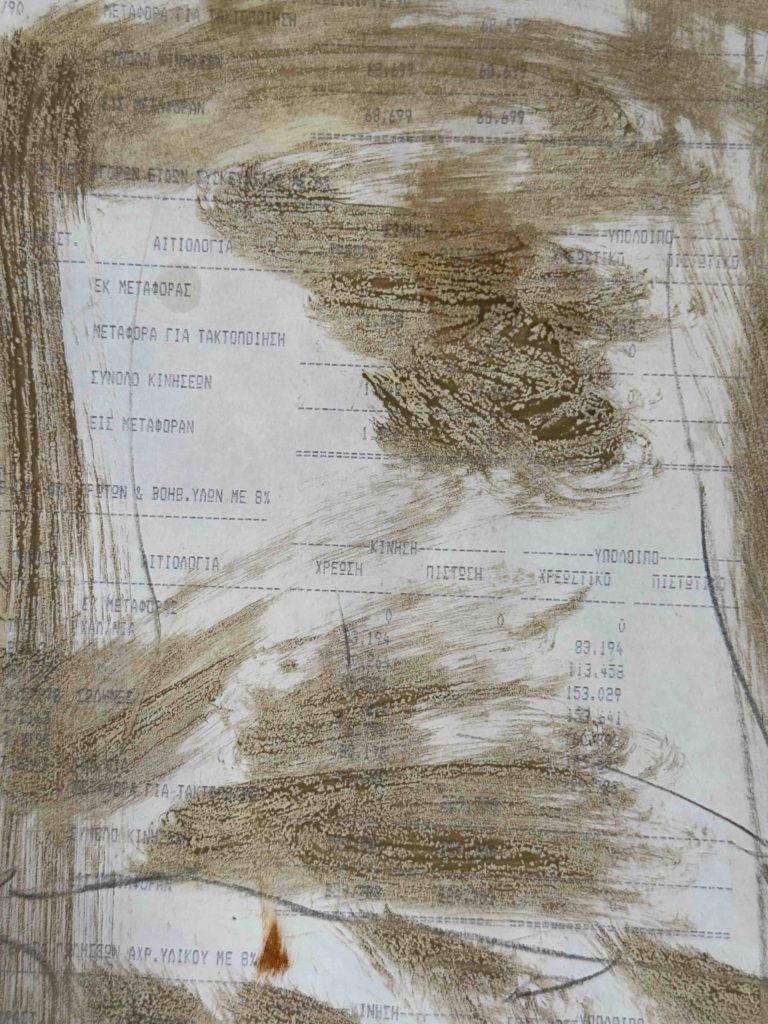

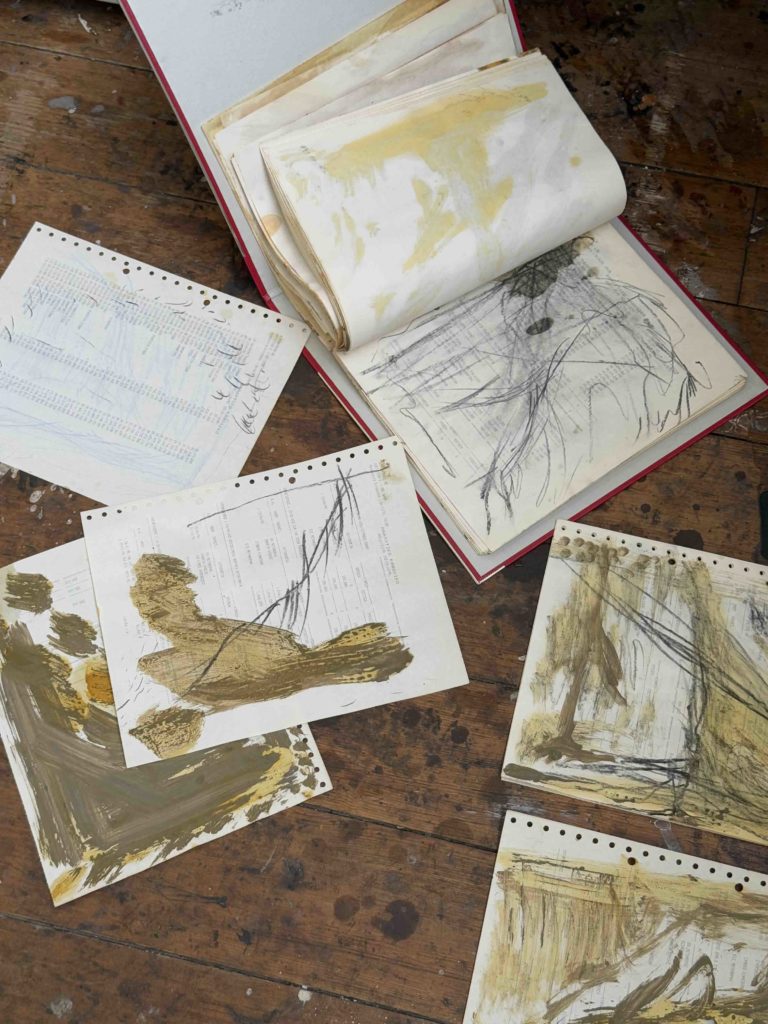

Her large paintings often resemble writing and inner landscapes. At first sight one might think of painting from the 1950s — Art Informel and elements of Abstract Expressionism. I see the paintings as part of a conceptual lexicon, a reflection of signs and language in the material world. The companions are palpably alive in the paintings, where titles play a role equal to brushes and colors. Take, for example, The Reader Interrogates Narrative, but Poetry Interrogates the Reader 1–5 (2022), shown at Kunstmuseum Appenzell in March 2024. The work is comprised of five medium-size canvases, presented in a row next to each other, formally suggesting a narrative. A sense of incompleteness pervades, and the surfaces recall stains left by handwriting on a piece of paper as well as bodily fluids. Thick, monochromatic surfaces, a rehearsal for a drawing, and pieces of found fabrics are blurred into each other. The title is a direct quote from a work by the poet Dionne Brand. The paintings and their conceptual frame become a literal materialization of nomenclature, the calling of a name, a summoning of something precise, like a linguistical pattern that is not fully articulated, creating the conditions of the work. If nomenclature refers to a system of naming and making sense of the surrounding world, in Pavlou’s case it operates on the margins — on its spectral side. On the one hand there is a direct relation to the actual etymological meaning of the word, calling something a name, summoning characters from literature and art history that live in the studio of the artist, sometimes in her own body or in the lengthy process of making the paintings. On the other hand, this name-giving system deals with the failure of names as they indicate inchoate states, inner landscapes, gaps of language and of emotion.

It is a sort of spectral nomenclature that Pavlou’s work presents, both within the surfaces of the paintings and the cloud of words and references around them. It is getting dark in my reality, and I take a swim. In the distance I see a lighthouse flickering in intervals. I think of the paintings, their lexicons and their summoning: those inner landscapes and the actuality of inner landscapes for me. “Actuality is when the lighthouse is dark between the flashes,” I say to myself as I swim, a line that Pavlou wrote in 2023. It is there and it is not, like intervals between memorable heartbeats, like Shelley’s body being engulfed hundreds of years ago and alive in me at this very moment. What inhabits a name? What inhabits a gesture?

“Literature and processes are at the core of my practice,” she tells me. And some processes take a long time, or a time that opens up lived experience to older temporalities. For example, take her diptych Virginia (2023). Its name references the dead writer Virginia Woolf, whose name Anastasia has for many years carried on her right arm in black ink. The diptych is made of oil, water, and gesso mounted on two canvases. One of them is gray, slightly shorter in height. The other is a reddish brown. Both incorporate gestures, small sculptural elements on the surface, like remnants of a temporality that is present and not fully accessible. To me it is like the endless letters exchanged by Virginia and Vita through the decades, sometimes warm, sometimes distant, sometimes surface level, sometimes containing a whole book, a whole universe desiring to be a love letter. The gesso creates patterns, pockets of time and lived experiences from different temporalities but also somatic remnants of the artist herself.

Pavlou’s latest solo exhibition also plays with temporality, anticipation, and elements of posterity. Curated by Roman Kurzmeyer, it is titled “Notes and Counter Notes on the Light that Burns,” and it took place at Atelier Amden, among the mountains in Switzerland.

The exhibition fluctuates somewhere between a conceptual work and a stage rehearsal. It is performative on many levels. For one thing, it lasted for just three hours on a Sunday afternoon in May 2025, yet its preparation took several weeks and included planned scores. Secondly, it is a real rehearsal, in the sense that its execution prepares the ground for an exhibition that will take place in Athens in September 2025 and is titled “The Light that Burns.” The stage in this case is a location consisting of barns, sun, wind, rain, and snow near Lake Walensee, a place where, in the early twentieth century, a social and artistic experiment took place in the form of an artist colony around the painter Otto Meyer-Amden (1885–1933).

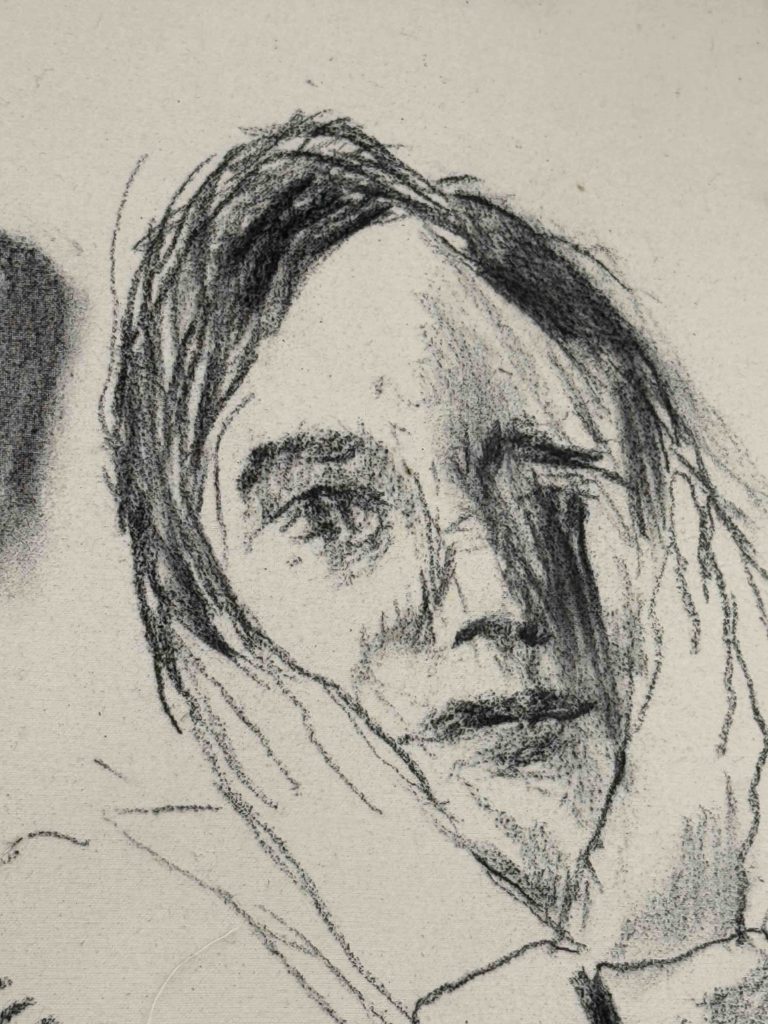

“The Light that Burns” is borrowed from the title of a 1922 book by the Greek Symbolist writer Kostas Varnalis,[2] that Anastasia has been carrying for ten years as a companion and is now for the first time entering the visual vocabulary of a presentation. When the artist first went to Amden, earlier in the year, it was still snowing and cold. Later in spring, when she returned, she brought with her a small self-portrait to be presented inside a barn. The face has a melancholic iconography, with the left hand touching the cheek, for me evoking John the Evangelist. Another self-portrait will go to Athens — like a Janus face spread across Europe. The presentation also includes two larger drawings that were made in the area and are part of a vocabulary the artist has developed over the past five years. Presented indoors, The Dreamer Dreams (2025) depicts the handwritten word “Possibility” repeated five times. The word entered her artistic lexicon during her second year of art school, alongside other elements such as depictions of spiderwebs or certain repeated pictorial gestures. Every time a new gaze is mirrored, a new aspect of that vocabulary emerges. The spiderweb in Amden is titled Thought’s Real Glow (2025), and it stood outdoors, on the outer wall of the barn, in contact with the wind for the duration of the exhibition. The work itself was made in approximately fifteen minutes, while the calculations for its making lasted for weeks. The artist recalls that the work was made and the canvas stretched inside the barn while it was raining heavily. Hay and stains made their way into the work. In this artwork/exhibition rehearsal, temporalities merge and re-emerge, creating gaps, including dead companions and slippages of the natural and the artistic, the body and the infinite. A few weeks ago Pavlou sent me a list of books that are by her side, or have been for a while:

[2] Published under the pen name Dimos Tanalias.

- The Life of Forms in Art by Henri Focillon (“That doesn’t really leave from the studio, I have it almost always.”)

- The Space of Literature by Maurice Blanchot (“Currently on my second read of this, and I am pretty sure there is gonna be a third.”)

- Art and Objecthood by Michael Fried (“I read this while I was working on my presentation at the Amden Atelier, and then brought it back to the studio.”)

- The Buddha In Daily Life: An Intro to the Buddhism of Nichiren Daishonin by Richard G. Causton (“Gifted to me by my friend Margherita after telling her how much I enjoyed reading Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind.”)

- The following books I plan on reading in London as part of my research there: The Theater and Its Double by Antonin Artaud; Collected Poems and Other Verse by Stéphane Mallarmé; Aesthetics of Installation Art by Juliane Rebentisch (“I’ve already read this twice.”); Must We Mean What We Say? by Stanley Cavell; Absorption and Theatricality by Michael Fried

It is a list I very much enjoy receiving, and parts of it I know intimately. There is a preoccupation with forms, signs, and the communication of dynamic traces that may express the unspeakable. Already in these books, like in her paintings, there is a preoccupation with how absence is experienced, absence as a sort of presence, a nothingness that activates an inner theater, like the one I am in. As a matter of fact, I happened to carry a copy of The Space of Literature with me in my travels. I read this text of Blanchot through the years in clear intervals, like a companion, a bit like visiting places connected with the Shelleys, but in the portable format of a book. I turn to the book as a sign — a form that connects my reality in Lerici to Pavlou’s studio in Basel, through time and in time. Of the many references coming from literature — names, citations, lexicons, and commencements — the space of her paintings is for me, right now, the inner landscape of literature. It is an absence, it is a landscape made of repetitions and slippages of exterior and interior. Blanchot writes extensively about spaces where the exterior and the interior play a pattern of appearance and disappearance. “What can be said of this interiority of the exterior,” he writes. Blanchot takes an experience by poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) on the island of Capri as an example of the poet finding a moment of Openness in which “the infinite penetrates so intimately that it is as though the shining stars rested on the breast.” Can this place really be accessed? And how could one access it? “Abandoned, exposed upon the mountains of the heart,” writes Rilke.[3] And this is the space I am experiencing right now in Lerici. Dinner for one. A lighthouse in the distance. A rehearsal for the coming ten years. Oysters eaten and companions shared with Pavlou’s works: Virginia, Percy, Dionne, Maurice, spiderwebs, and possibility. An inner landscape where significations are at once transformed and inverted. Like my beating heart, misaligned. Like the gaps between the flashing of the lighthouse in the distance. Actuality. Spectral nomenclatures.

[3] Maurice Blanchot, The Space of Literature, trans. Ann Smock (University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 136-38.