Did it matter then, she asked herself, walking toward Bond Street, did it matter that she must inevitably cease completely? All this must go on without her; did she resent it; or did it not become consoling to believe that death ended absolutely?

— Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway (1925)

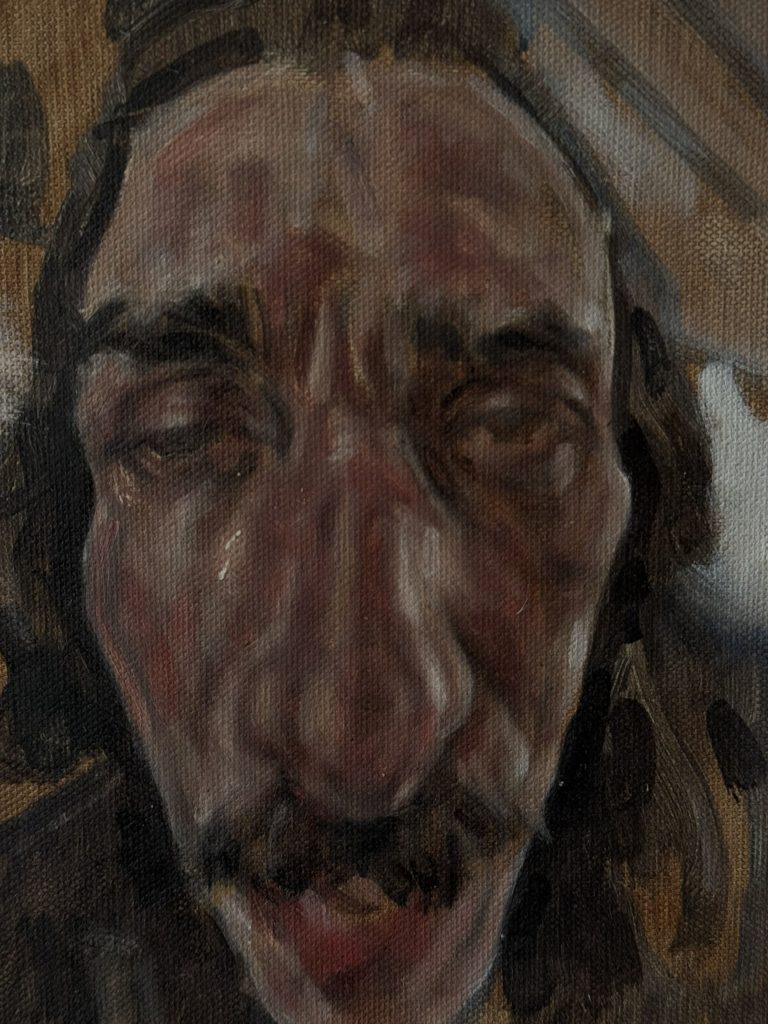

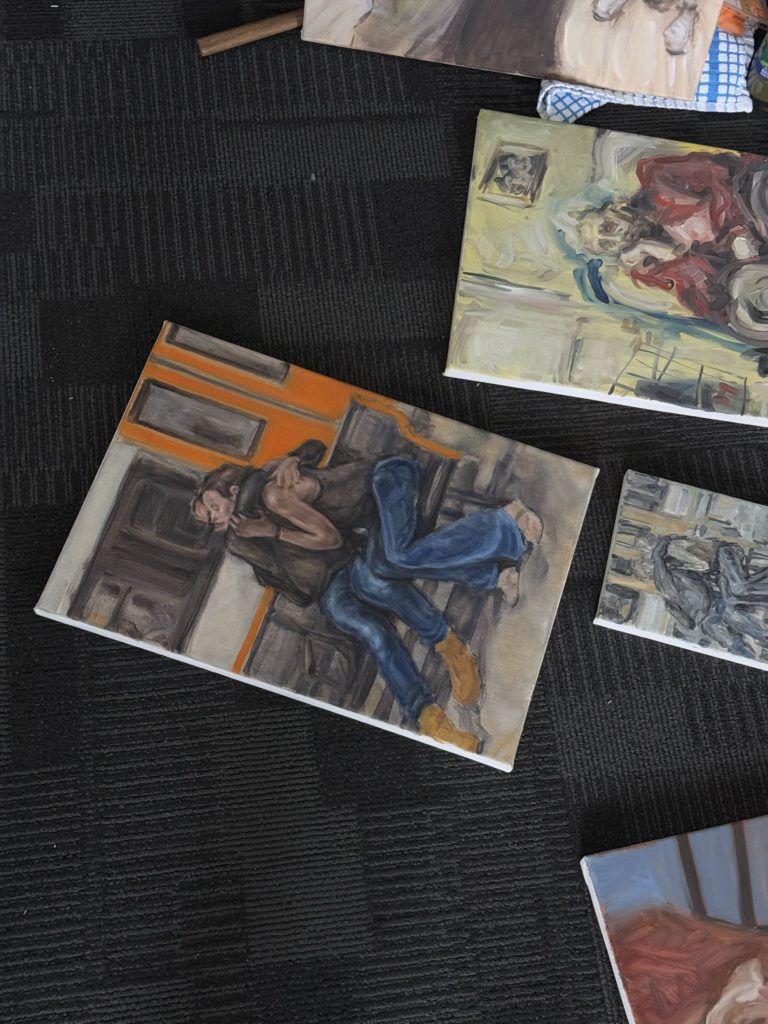

In Adam Patrick Grant’s studio in London, the air feels dense, almost particulate. The space seems less a room than an archive of gestures: an environment where everything, from a line drawn on a page to a brushstroke left unfinished, holds the residue of a sustained act of looking. Along the walls, finished and unfinished canvases; on the floor, sheets covered in studies of the human body drawn with a draftsmanship that is both precise and tender. Grant moves quickly, almost restlessly, though the room, lifting a box from a corner and placing it on the floor. From it, he pulls out a series of sketchbooks, each labeled and dated: Observational Drawing Book Nov–Jan 23. He places them on the floor and tells me I’m free to look through them. I do — gladly, almost greedily.

I sit cross-legged on the moquette floor, the sketchbooks spread around me like a private constellation. Their pages are filled with rapid drawings made from life — in cafés or pubs, on buses, at friends’ houses — interspersed with brief notes and fragments throughout. These drawings are not studies for paintings in a literal sense, but a record of looking: a way of learning how to see and how to remember. Spending time with them, I realize that Grant’s work does not begin with an image so much as with an attitude: a particle of attention. Over time, this accumulation of small, devotional acts of seeing becomes something larger — a way of holding the world still, if only for a moment.

Grant has drawn regularly since childhood and worked across many mediums, but it is though oil painting — a practice he has pursued consistently over the past three years — that this attentiveness has found its most resonant form.

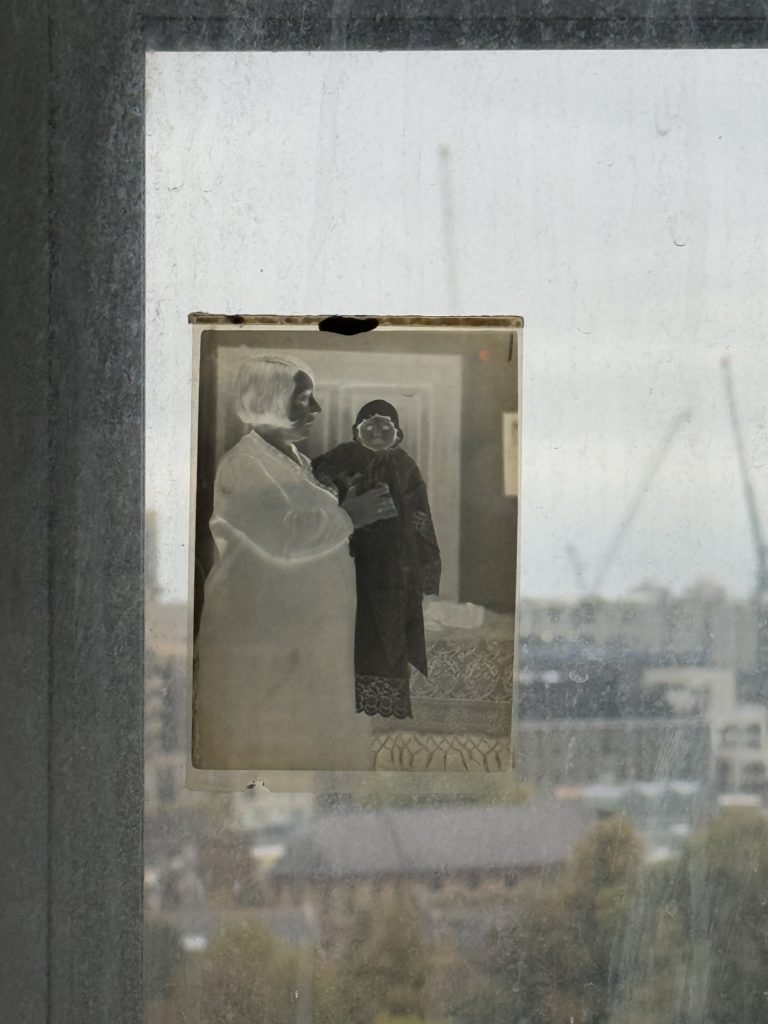

Before he began painting, Grant trained in film. He never pursued it formally, but the impulse to frame and preserve the fleeting was already present. When I ask him what kind of films he made as a student, he laughs and says he can hardly recall — except for one. It was a short video, he tells me, showing a mother and her child caught in a brief moment of tenderness. It’s not difficult to understand why he remembers this specific film. The instinct to locate and linger within a small, unspectacular moment, to find intimacy within the everyday, was there from the beginning. Even before he turned to paint, Grant was searching for that fragile point of contact between seeing and knowing, between witness and recognition.

Today, that impulse finds its form in painting, though photography remains its quiet foundation. Grant produces and collects images: connections with family, friends, or passing encounters that act as fragments of life or a city’s ongoing theater. From this vast personal archive he selects individual frames, moments that resist explanation. These are the images that become paintings.

Walking, for Grant, is not merely a way of gathering material but a way of thinking — a rhythm through which memory and perception align. He speaks of processing and coming to terms with things while observing his surroundings, how the environment can seem to mirror one’s own state of mind. This quiet dialogue between outer and inner worlds lies at the core of his practice.

But the sources of this work extend far beyond his own photographs. On the walls and shelves in his studio are stacks of old prints and postcards: family photos picked up in second-hand markets, anonymous portraits, devotional pictures, fragments of the visual detritus that circulates though the city. He studies these items as carefully as he studies his own images, attentive to the way certain faces or gestures seem to glow faintly with an inner residue of emotion. One particular image, pinned to the wall, catches my attention — a small, somewhat awkward sacred picture, its iconography unfamiliar. “I found it in Italy,” he tells me. “Something about it stayed with me.” The combination of reverence and curiosity, of devotion and estrangement, feels entirely characteristic of his way of looking. For Grant, every image — whether found, inherited, or self-made — carries the potential to open a space of relation, a chance to approach another person, another life.

The scene in 13:47 10.02.23 (2025), for example, seems, at first, ordinary: a man elegantly dressed, walking toward us through a London street. His face carries a weary, almost pained expression. In one hand he holds a bouquet of flowers; in the other, a crutch. Did he injure himself, or has he always carried that weight? Why so many flowers — a celebration, an apology, a farewell? Everything appears visible, and yet nothing quite reveals itself.

Grant’s paintings possess this paradoxical clarity. They begin in documentation, in the visual language of photography, yet through paint they become something spectral — tender, uncertain, haunted by the moment that has already passed. Roland Barthes, in Camera Lucida (1980), called the photograph’s truth its that-has-been, a proof of what once existed. His paintings undermine that certainty: the timestamp that tempts us with evidence becomes, in his hands, a site of ambiguity. The factual turns into the enigmatic — the photographic punctum reimagined through paint.

When I think of Grant’s figures, I think of Woolf’s London — those passing lives glimpsed from a distance, the beauty and melancholy of the ordinary. Like Woolf’s characters moving through the city, Grant’s subjects seem suspended between the living and the vanishing — the simultaneity of presence and disappearance that defines consciousness. Each of his paintings seems to hold both the living and the vanishing at once: a body moving toward us and away in the same breath.

There is an ethics of looking that runs through all of this. The people Grant paints are often unaware of being seen. Yet this, too, mirrors the reality of urban life. As Georg Simmel wrote, the city teaches its inhabitants a kind of protective indifference, a blasé surface that shields them from overstimulation.1 Grant’s view, however, is less about exposure than about recognition. He searches for those brief instants when the façade falters — when someone, however unknowingly, lets their guard slip, revealing a trace of emotion through a gesture, a glance, the weight of a shoulder. “Reflecting on the moment through painting,” he says, “is a way of really getting to know someone. Someone you might otherwise never meet, or never know in that way.”

“I’ve tried to use painting as a way of engaging with the emotion and humanity of observed moments without as much of the invasive indexicality of shared photography. That obviously can’t erase the complications of authorship that arise with observational representation though. I always want to root the pictures in empathy and a love of people but the nature of it can often feel intrusive. At the moment I’m trying to explore similar themes through more participatory kinds of portraiture while continuing to focus on truths found in passing moments.”

13:47 10.02.23 was part of Grant’s solo show “Mourning Dance” (2025) at 243Luz in Margate. The title itself feels like a paradox — two words from two different emotional registers held together. Mourning implies loss, an aftermath; dance suggest vitality, joy, motion. Together they form a very fragile dialectic: a grief that moves, movement that grieves.

Grant explains that the phrase “Mourning Dance” was originally a personal and quiet dedication to someone who had been instrumental in his decision to pursue painting. The words were intended for them alone, but what drew him to the phrase was its tension: an image of conflicting emotions coexisting in fragile balance. It became a touchstone for the exhibition, guiding both its imagery and its tone during a period of personal change.

The works in the exhibition continued his exploration of temporality and tenderness, translating ordinary encounters into moments of bright suspension. In 18:00 12.08.23 (2025), two unidentified figures embracing on a bench, a vehicle passing behind them. Is it a farewell? A reconciliation? Or simply a gesture of affection? The brushstrokes are quick yet deliberate: everything is visible and yet not fully knowable. What unfolds before our eyes is at once clear and obscure, because we do not — cannot — know the story that led to this instant. We can only suppose. And the more we look, searching for clues that might offer resolution, the more we come to know these figures not through narrative, but through proximity and the intimacy that grows from looking closely.

The same could be said of 22:02 09-07-23 (2025). At first glance, the scene might resemble a dance hall or a social gathering, but on closer inspection one begins to doubt: perhaps — and it is important to keep that perhaps — the two figures in the foreground are not dancing at all. They may be about to embrace; they may be in conflict. The expression of the figure on the left, dressed in red, seems almost tense. Are they arguing? It hardly matters. What matters is the act of questioning itself — the way these uncertainties draw us deeper into the painting, until we find ourselves suspended within its own ambiguity.

Across the exhibitions, gestures return and shift: a turn of the head, a body leaning forward, a hand extended toward another. Each one feels both familiar and distant, as if time itself were hesitating — pausing long enough to be seen.

Grant describes how, in revisiting memories through drawing or painting, new truths often emerge alongside the original emotion. “Mourning Dance,” he notes, gathered works that shared those layered feelings, allowing them to a sense that grief is not static but fluid, an energy that circulates through anything and everything around you.

The emotional range of “Mourning Dance” echoed the duality of its title. There was a quietness to the paintings, but also a kind of interior movement — a sense that grief, in Grant’s hands, is not static but fluid, an energy that circulates through bodies and spaces. To mourn, here, is not simply to remember, but to keep alive: to continue to look, to keep attending to the world. The show’s atmosphere was neither somber nor consoling. Instead, it occupied that delicate in-between space where sorrow shades into tenderness, and the act of seeing becomes an act of care.

Back in his studio, surrounded by unfinished canvases and open notebooks, that sense of care is palpable. To paint, for Grant, is to stay with the image — to hold it in tension between fact and feeling, between what is recorded and what is remembered. It’s as if he waits for the paining to tell him when it’s done, as though the image itself must decide when it can rest.

This practice of attention — at once analytical and emotional — feels inseparable from the larger ethic of his work. Grant’s archive is not one of control but of care. He gathers images not to process them but to accompany them, to learn what they revel if given time and tenderness. The city, in his paintings, becomes a site of silent encounter: a space where the anonymous and the intimate, the living and the lost, coexist in perpetual flux.

In this sense, his paintings share an affinity with Woolf’s words — their rhythm of perception, their openness to fleeting experience. Both seem to recognize that looks are always provisional, that what is most vivid hovers on the edge of disappearance. In Grant’s work, the ordinary becomes luminous precisely because it is transient.

When I think again of the man in 13:47 10.02.23 (2025) — his flowers, his crutch, his unreadable expression — I realize that the painting doesn’t ask for interpretation. It asks for accompaniment, for the viewer’s willingness to stay in the uncertainty of the moment. Everything is visible; nothing is entirely known. Perhaps that is the generosity of Grant’s particle: to remind us that attention itself is a form of empathy, that to look closely is to care.

1Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903), in The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. D. Weinstein, trans. Kurt Wolff (New York: Free Press, 1950), 409–424.