Working across performance, installation, sound, and film, Solomon Garçon plays on the role of artist as director. He breaks the fourth wall in spaces where life happens — the spaces of sex and of privacy — to create film sets where lifelessness crawls from the walls: the austere mise-en-scène of a home. Architecture reveals itself to be an active listener and spectator, recording us, mutating and morphing. The landlord-painted walls become characters while we act in their set, witnessing violence and reacting to it in case someone might catch us looking. Between a prop on a TV set and the real thing, between a wax mannequin and a celebrity in the flesh, between a porn star and her home, each double has been formed by our spectatorship, and neither part exists without it. While Garçon’s spaces are reserved and cold, flattened for viewing, they become animated with sound and scent once a body enters.

Tosia Leniarska: I’ve been following you for years, but only recently realized you have a contemporary art practice. I initially saw your work through London’s clubs, in the experimental music and fashion scenes. What brought you to where you are now?

Solomon Garçon: Yeah, I was really outside pre-pandemic, squatting in various South East London spots that were previously churches and now clubs or event spaces. But what changed? I had two kids, which is crazy, during lockdown. I actually live in the house I grew up in now. I think the pandemic really shifted my practice, because I was often working with a lot of people before, and then I started working a lot more solo. I developed a practice that was probably sparked by being indoors and watching a lot of reality TV.

TL Interesting. Which shows?

SG Real Housewives of Atlanta is my favorite of all time. But I’ve watched a lot of other things, like The Kardashians, Baddies, Bad Girls Club, Big Brother, 90 Day Fiancé, The Osbournes, The Simple Life, Faking It, Dirty Sanchez, Flavor of Love, and The Braxtons. I don’t really watch the new British ones — they’re not extroverted enough for me.

TL How do you bring that into the context of galleries and art fairs?

SG For my show at Studio Voltaire, I hid a huge sub-bass in the corner of the room, boarded up so it resembled an old boiler that used to be there. It played extremely low frequencies through the space. It was almost vibrating, but you couldn’t exactly tell where the sound was coming from, and it revealed some of the architecture of the space, because you would feel it in certain pockets of the space, and in certain areas you wouldn’t feel it at all. On top of that, I had a little speaker right next to the window that played a little clip of Kandi Burruss from Real Housewives of Atlanta but I had EQ’d that so it sounded like it was two people speaking just outside the space. I’ve been obsessed with this Real Housewives scene where NeNe Leakes tries to stop people from entering her closet, but they do anyway, and the fourth wall breaks — a cameraman gets pulled into the drama. I love moments when the performance breaks down.

TL At Liste, you also used scent — Calvin Klein’s Obsession. Why that one?

SG Such a good name, no? Obsession is used in wild life filming to lure big cats to the camera; it contains a pheromone derived from civets. I wanted a scent that would animate the canvas next to it. Both works were suede, marked by bodies that had touched the material, and I like when the audience has to get physically close to a work, to “perform” in order to reveal it.

TL You’ve done a lot of work with performance and sound. But in the Liste presentation, you’re using scent, and you name scopophilia as your subject, so this fetishization of sight, or vision. What does that transition between different senses mean to you?

SG I’m really a performer, to be honest. I work with theatrics. One of the canvases made with red leather had this very exact Pantone-matched Rimmel London lipstick on it, which you couldn’t see at all unless you were right up close to it.

TL The lipstick canvas was so sticky and tactile — it made me squirm.

SG I love that kind of discomfort.

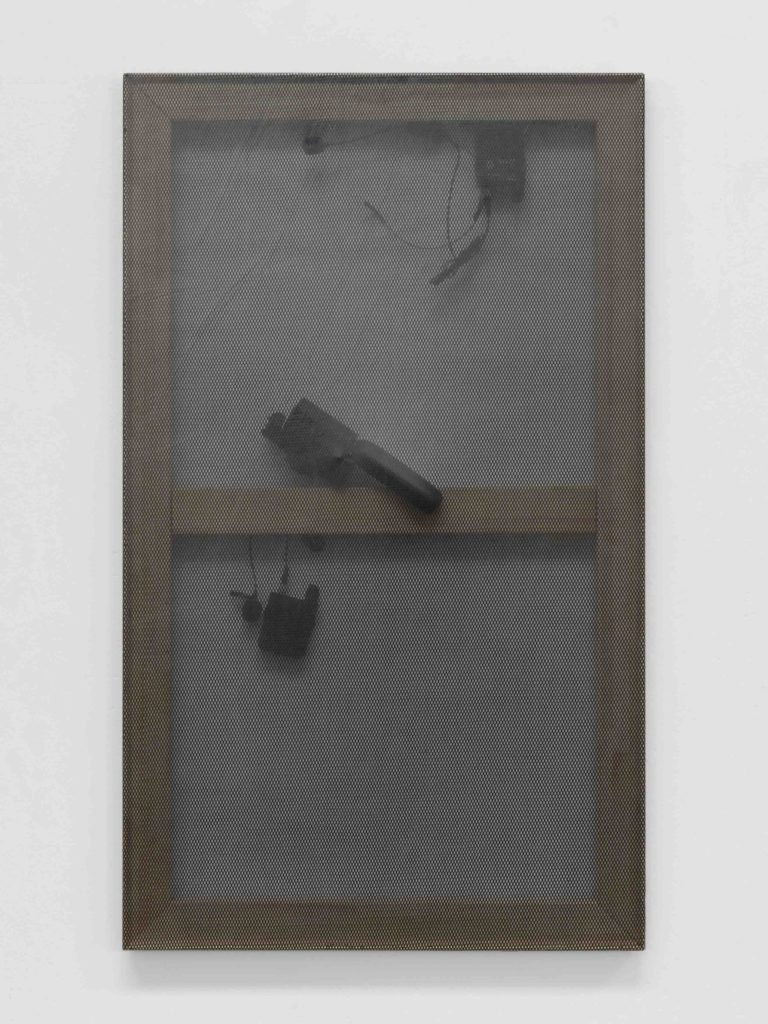

TL Was Liste the first time you recorded the audience?

SG Yes, I thought it was funny to do it there, because I actually like the context of an art fair. I didn’t think I would. It has this film-set feeling where everybody’s in the same space and everybody is filming each other. It creates this tension where you are really in a space where you’re not sure who’s who. Especially at the booth, where they’re really trying to recognize people.

TL Is there an element of creating a user experience for the viewers, like you’re guiding them through the set?

SG Exactly. At Liste, there was one couple who came to visit. And when the wife saw the sign that said that this booth is recording audio, she pushed her lawyer husband out of the booth because he was on an important phone call. It’s funny how something so flat and traditional as a painting can animate people.

TL The set design of your Liste booth with your sculptures of heels in plastic bags had this really dark ’80s vibe, like American Psycho (2000) or CSI Miami (2002–12).

SG I’m quite into this quality of “filmness.” The other day, I found this photo from Harrods in 2006 of a cobra inside a glass case that was guarding a pair of £62,000 shoes.

TL The fetish object!

SG There’s a kind of capturing in photography and filming that mirrors what I used to do in performance. Low-frequency sub- bass in dub, noise, and hip-hop is used in a way to locate bodies in space — and I found that in geology, similar frequencies are used to find crystals deep underground. I see the camera as a modern version of that: a tool we use to mine for viral moments, something real and immediate. Reality TV works the same way — this mining and capturing of something “raw.”

TL I guess there is a fetish element to it, which must be why you’re referencing scopophilia. With the plastic bags that you use, whether they are see-through or black, there is this voyeuristic relationship to filming crime or violence.

SG I think that is how we interact with objects now, and how the camera flattens everything into an object.

TL Do you use photography in your work?

SG I do. In the show at 243 Luz, there was a shot of David Attenborough’s hand, which was actually from Madame Tussauds. But it looks so hyper-real that it makes it feel like I’ve actually got a shot of his hand. I also pulled it into this context of hook-up apps. I was using a lot of images that I’d taken, and I was using them as a mood board for a TV show which focuses on this male escort who is mostly based at home, but also based in people’s houses. The way that it’s filmed is a bit like The Bear (2022–ongoing), where you have a lot of flashing scenes, and all these close-ups that make you disoriented, so you can’t actually tell whether this guy is at home or he’s in other people’s homes, or what’s going on and which one is his home. That’s something I’m working on at the moment.

TL Are you going to actually make the show?

SG Not really. I’m more into the TV production process than the show itself. I got a message from someone working in the production of Grand Designs the other day, which was funny. Maybe I’d do a Sniffies ad for free just because I love Sniffies. I once made a film with Hilary Lloyd where I was just navigating Sniffies.

TL It’s one of the only apps where people actually break social bubbles.

SG I honestly see it as the digital underground. I feel like clubs got completely gentrified, but used to be a space where you would clash with people from completely different worlds, whereas now, everybody’s like a pop star. These apps are one of the only ways in the digital realm where you’re able to find new experiences.

TL There was an element of the domestic in your Rose Easton show, where you used the “landlord special” magnolia wall paint on everything, including your sculptures. What were those sculptural objects?

SG Yeah, we actually Pantoned the paint to the exact color of my kitchen. The sculpture, Legba’s Dog (2022), is a body cam holder — an exoskeleton with a spine and arm extensions that wraps around the body. I love that kind of thing from film and TV production. All the pipes in the space were fake, inserted by us, but no one noticed. You enter a space assuming the architecture is just there, that you’re not being watched. Even in a gallery, people rarely question it. The plug points were fake, the windows boarded up. It was a full spatial takeover — a flattening— with this body on the floor.

TL I’ve been to that gallery and I’ve seen it without the pipes, and I still didn’t notice that.

SG We just don’t question architecture so much, but it is a driving force in the way that we move. How you move around spaces is built into the architecture.

TL Do you find this performativity different in the music and performance context and the visual art context?

SG Usually, I’m thinking about disorienting the audience. And with performance work, I’m really into playing with your eyes, directing where your eyes are. Recently, I’ve been doing these performances with heavy strobe, where I’m performing in front of the strobe, and it creates this feeling that’s almost like stop motion. Like early Disney, or shadow theater, where each blink becomes a new frame. Our eyes essentially become a camera.

TL It was a kind of power electronics, noise music set, right? There’s a level of discomfort you’re putting the audience in across these mediums.

SG Yes, my band together with John T. Gast. I do like creating some sort of a guttural drop, or like a slap at the end. You have to use your body to do that, you know? You have to use your eyes to look again. You have to investigate.