Ruoru Mou’s practice folds together industry, ownership, and inheritance. Working across sculpture and installation, she manipulates factory debris and fragments of family history to trace the material politics of value and care.

Her recent exhibition “Fortunate” at Cell Project Space, London, continues an ongoing inquiry into the infrastructures of production that shape both luxury and survival. Through bag molds, reconstituted skins, and a snow blizzard in an enclosed cold room, Mou situates the body within systems of classification, extraction, and circulation, exposing how beauty and exhaustion are often manufactured side by side.

In this conversation, Mou reflects on the material and conceptual foundations of her practice: the industrial and handmade processes that inform her sculptural methods, and the entanglement of labor, bureaucracy, debt, landscape, and ornament within her visual language. Speaking from a position that bridges personal and structural histories, she considers how forms of making might metabolize inherited economies of care and value, and how the residues of production – from tanned hides to shredded receipts – can be reworked into new vocabularies of property, authorship, agency, and desire.

Olivia Aherne: We’re speaking only weeks after the opening of your latest exhibition, “Fortunate,” at Cell Project Space in London. Drawing on industrial forms, cinematic references, bureaucratic residue, and factory waste, the commission explores the material politics of value — tracing how it’s produced, circulated, and regulated through the bodies and systems that sustain it. How did this new body of work begin to take shape, both conceptually and materially?

Ruoru Mou: The exhibition grew from a long period of sitting with different subjects and materials, especially a set of leather stamping dies I found in small factories near Florence. These tools, used by migrant workers to produce luxury bags for brands like Celine or Gucci, fascinated me as objects of both precision and violence –– they press, inscribe, and repeat, almost rhythmically. Handling them, I became aware of their sharpness and the risk of injury, a reminder of wounded flesh and the body’s vulnerability in the studio, factory, or kitchen. Each mold is etched with lines that dictate where stitches or stamps should fall, precise marks of authorship and control. Each one is tagged with “art,” short for “article,” followed by a number. That slippage between art and article, between authenticity and imitation, was so interesting to me. I was reading Byung-Chul Han’s Shanzhai: Deconstruction in Chinese (2011), which describes how, in Chinese art traditions, inscriptions accumulate through collective gestures rather than asserting a single author. I became focused on this relationship between authorship and legitimacy, how we decide when an object, whether a luxury bag or an artwork, is considered real or fake, and how arbitrary those definitions can be. The same logic operates in contemporary art: questions of how a work is made, who inscribes it, and how authorship is constructed differ radically between Western and Eastern traditions. Some of the leather molds in the show still bear original factory engravings; others carry mine. The work deliberately confuses these layers, collapsing the distinction between truth and imitation, original and reproduced.

I began combining the molds with the “skins” that I’d developed for a previous work, Hung Out to Dry, holding the bag (2025), made from industrial and restaurant waste: grease, gelatin, starch. Cooked, cast, and left to shrink and sweat over time, I pressed those skins into the molds, trapping light through them. It became a way of looking through layers of skin – literal and phantasmical — to see how bodies, labor, and value are inscribed. That’s where the exhibition began: from an interest in how systems of making and value intertwine, where the gestures of the hand meet industrial processes caught between ornament and wound, and how ideas of authenticity slip between production, imitation, and desire.

OA: Reuse seems to play an important role in your practice — not just materially but also conceptually. How do you think about the lifespan of a work, or the point at which a remnant becomes raw material again? And in that process, how does your own sense of value — what is worth preserving, reworking, or discarding — intersect with the broader systems of value that circulate within an art economy

RM: I think a lot about value and how hierarchies of value can be disrupted. Reuse, for me, is both a methodology and a subject, where materials circulate, transform, and never fully resolve. Not everything has to be new; I’m drawn to what’s been chewed up, metabolized, or rejected, a different kind of material index with history and discomfort built in. There’s always this tension between shame and renewal, old work can feel embarrassing, yet it’s the ground the new work grows from. I’m interested in that emotional friction, and in how something old, or abject, wet, or grotesque can, through process and form, become ornate or desirable again and vice versa. That slippage is where questions of value, impurity, and display converge for me.

With the casting of the skins for Hung Out to Dry, Holding the Bag (2025), for example, the process is very physical: casting, pressing, pouring, re-molding. My molds are huge. Over two meters long, so I’m often stretching my body beyond its limits. That exertion and exhaustion defines its own kind of finality. Everything happens fast, within minutes before the mixture sets. It’s like orchestrating a small disaster: pouring grease, soy sauce, gelatin, and then watching them solidify. It took about five months of failed recipe tests to get it right. The process reminds me of Chinese ink wash painting, where you have to anticipate how the ink seeps through the paper. That sensitivity to time, touch, and transformation has always stayed with me.

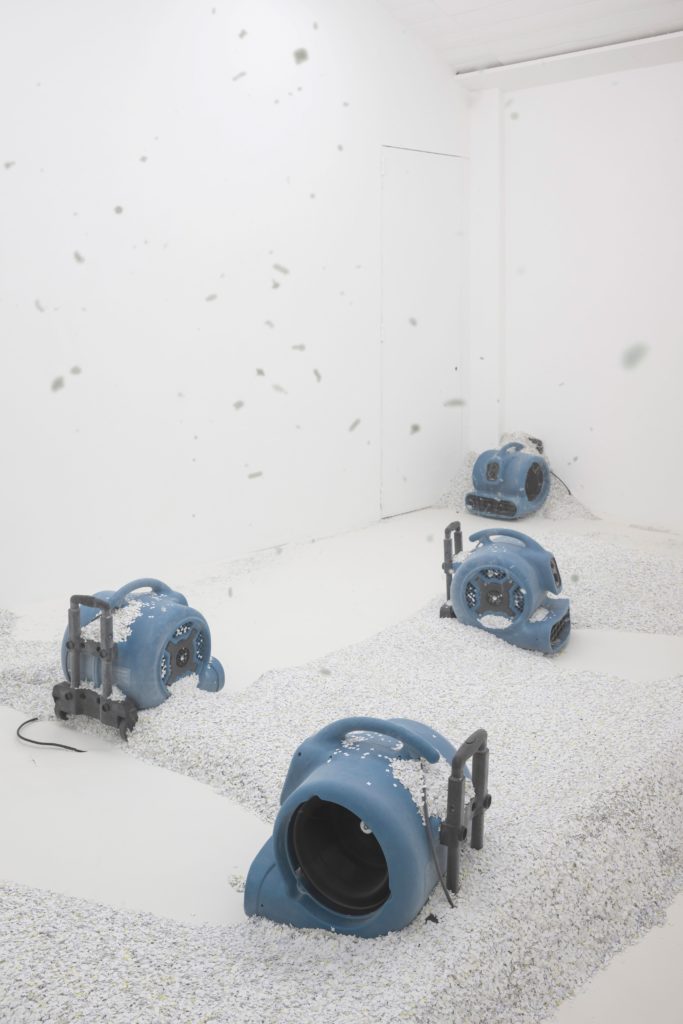

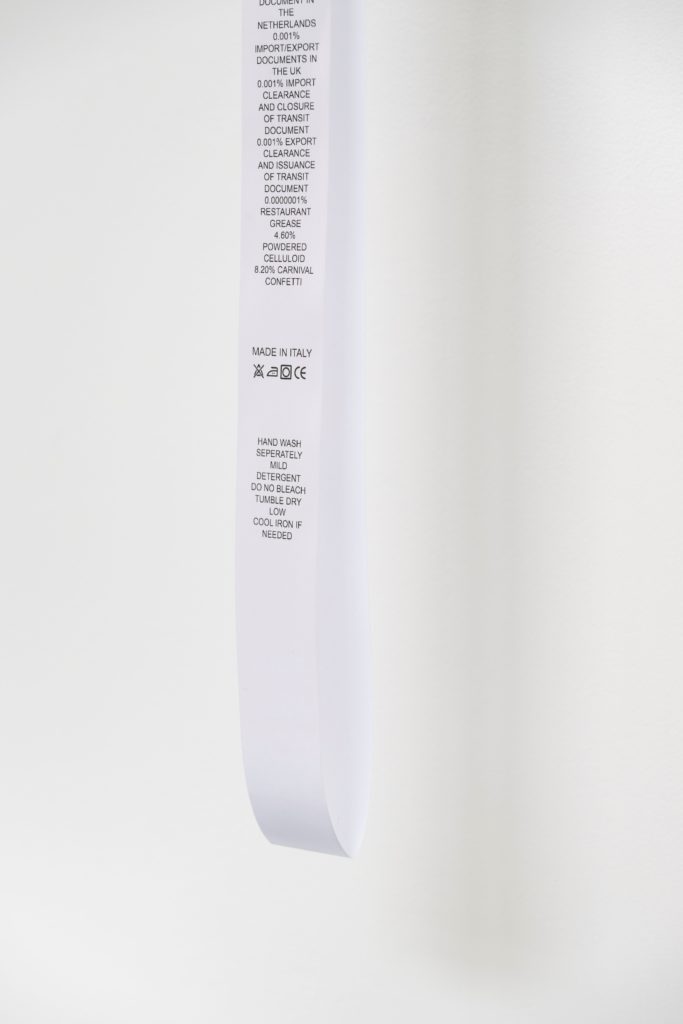

The skins have been subjected to refabrication in the history of citizenship and social belonging. The contiguity of skin and cloth, and the ways it’s arranged and transformed through the act of shredding is both rebellious and represents a painful process of transformation. In Dirty Snow (2025), I tried to foreground a particular subjectivity without representing anything. The wash label that’s installed on the wall next to the room arbitrarily lists the content of the “snow” — a mix of debris from the studio and factories, shredded documents, or surfaces that function as projected images of security. The shifting snowscape becomes a way for me to mess up the classification of value and life, whether that’s in everyday context or within the art economy.

OA: There’s a distinct undercurrent of science fiction in “Fortunate” — especially in the back room that you mention, where machinery and containment evoke a kind of speculative environment, that of an enclosed snow storm. What role does sci-fi play? Were there particular references, films, or ideas that shaped how you imagined this world and its relation to labor, technology, or the body?

RM: I was thinking a lot about what it means to live through uncertainty — this sense of waiting for a disaster to end, yet continuing to move through it without knowing when or if it ever will. I wanted that feeling to exist in the exhibition, initially through a kind of snowstorm effect: a room you could look into, filled with swirling, suspended matter. I was inspired by films like David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ (1999) and Richard Fleischer’s Soylent Green (1973), which feature synthetic environments, conveyor belts, and a kind of suspended materiality. I was also reading Exhalation (2019) by Ted Chiang and reflecting on the dichotomy between the role of a merchant and an alchemist. Storage spaces hidden in the backs of kitchens are usually where matter and information are preserved. They often appear in Western sci-fi as portals: hidden sites that store, process, or produce material and information. I wanted to play with that sense of temporality, how things are preserved, how bureaucracy moves, how bodies and systems endure and wait. The three maneki-neko cats, whose arms wave through the blizzard, is my attempt to evoke a sense of resilience in the uncertainty.

Around that time, I was revisiting this receipt holder that had been in my mother’s restaurant since I was a child. It carried a mistranslated English label that read “Collecting Fees Document.” I began thinking about receipts and care labels — both systems of classification and accountability — and how they relate to value, labor, and care. That’s how the work Collecting Fees Document (2025) emerged: as a way to collapse the space between skin and fabric, commerce and care, object and identity. The “snow content” in Dirty Snow also became part of that logic, listed like a material percentage in a label, performing the bureaucracy of care itself.

OA: This “snow content,” made from shredded documents and debt receipts to leather offcuts, carries such deeply personal, social, and industrial histories. How did you decide what to include, and in what ways do their origins and transformations speak to your broader concerns with systems of value, debt, and the conditions that shape who is recognized?

RM: For me, Dirty Snow reflects the traces of what defines a “natural person” — not just legal recognition, but the preconditions of who is considered acceptable or eligible to perform within society. Many of the shredded documents in the work come from my research into debt, including debt receipts from my parents’ early restaurant in the 1980s and records from a female credit union my grandmother helped establish to fund it. These materials carry histories of support, restriction, mobility, and precarity, how debt can enable opportunity while also trapping people within systems.

I also incorporated bureaucratic materials from labor and health offices, alongside leather offcuts. A remix of “dirty money” and “dirty work.”

OA: Landscape seems to recur in your work, not only as imagery, but as a way of composing and situating bodies, materials, and environments. What draws you to landscape as a structure or sensibility?

RM: I’ve always thought about landscape as a way of framing emotion and distance. Growing up surrounded by Renaissance painting while also learning Chinese ink wash techniques, I was drawn to how both traditions reimagine space. One through perspective, the other through permeability. When I’m working with installations like Dirty Snow, I think about how those histories shape the way I compose a scene. The vitrine, for example, becomes a kind of landscape, where desire, melancholy, and transformation unfold materially. It’s about trying to find language for that emotional terrain.

OA: There also seems to be a recurring tension between presence and disappearance – between revealing and withholding. How do ideas of absence play into this too?

RM: I’m really into this idea of “absencing,” especially through Byung-Chul Han’s writing. It also connects to my own upbringing — growing up in a Buddhist family while attending a Catholic school. Those two belief systems shaped how I understand space and perception: in Catholic spaces, light is directed and transcendent with stained glass filtering from above, whereas in Buddhist temples, the boundary between inside and outside is porous. That duality between “essencing” and “absencing” filters into my work. In the vitrines, Tease 001, Tease 002, and Tease 003 (all 2025), the translucent molds have a stained-glass quality where light shines through layers of skin. The back room with the snow landscape, by contrast, becomes total absence — a space where vision falters, and the subject itself starts to recede.

OA: And then there’s ornament, which feels like another layer in this conversation around visibility and surface…

RM: Yes. I came across Anne Anlin Cheng’s Ornamentalism (2018),which helped me understand how, historically, ornaments were dismissed as excessive, superfluous, or decorative, but they carry seductive and racialized histories. The wooden ornaments I used in the vitrine works once belonged to my grandfather’s carving, originally installed in my parent’s restaurant in the 1980s. Over time, it was taken down and I used the broken or fallen fragments in the work. At the time, I was thinking about how the fetishism of objects comes from the alienated labor around it, a lot of the fetish value is the opposite of use value. When we attend to the labor of the ornament and the fleshiness of the ornate, there’s this interesting tension between the beauty and terror, life and deprivation. The almost reliquary aspect ofthe bag molds in Tease (2025)somewhat speaks to this accessorial device of both utility and seduction