They remained oblivious to the worlds within worlds that existed just beyond the edge of their awareness and yet were present in their very midst.

– Cheryl Harris[1]

[1] Cheryl Harris, “Whiteness as Property,” in Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement (New Press, 1995), 276.

Building upon the experience of her grandmother, who worked in a company comprised exclusively of white employees, Cheryl Harris, in Whiteness as Property, confronts the systems that sustain life — understood as the recognition of this condition as such — alongside a set of conditions that enable access to material, public, and private privileges. In doing so, she engages with the intertwined concepts of race and property, affirming their relations in contingent systems that are inherently subordinated to our present. Starting from the historical expropriation of Native American lands, followed by the genocide of indigenous peoples and the complete and unconditional appropriation of Black bodies displaced from their homelands to the American colonies, Harris develops a semiotic association between the meanings and practices associated with notions and experiences of property as contingent to race and the valorization of whiteness as a form of assurance to property within a socially organized racial caste structure. In such systems, only Black subjects were subordinated to the condition of slavery, effectively rendered as possessed objects and so interdicted from any potential of survival. She writes: “Similarly, the conquest, removal, and extermination of Native American life and culture were ratified by conferring and acknowledging the property rights of whites in Native American land. Only white possession and occupation of land was validated and therefore privileged as a basis for property rights. The distinct forms of exploitation each contributed in varying ways to the construction of whiteness as property.”[2]

[2] Harris, “Whiteness as Property,” 278.

Although already embedded in existing social practices, between 1680 and 1682, the various Black Codes radically instituted the complete deprivation of rights for enslaved Black individuals; they were prohibited from traveling or moving independently, owning property, voting, assembling publicly, or possessing weapons; they had no right to education and were thereby deprived of any knowledge that would enable them to understand the condition to which they were subjected. No gatherings among enslaved people were permitted, thus denying them any circumstance of collective consciousness. Black enslaved individuals were rendered interchangeable, a “negro” equating to “money,”[3] and their identity conceived in opposition to the one of “whites” in its contingency with “free.” Harris, returning to the condition of her grandmother, continues: “Whiteness — the right to white identity as embraced by the law — is property if by ‘property’ one means all of a person’s legal rights.”[4]

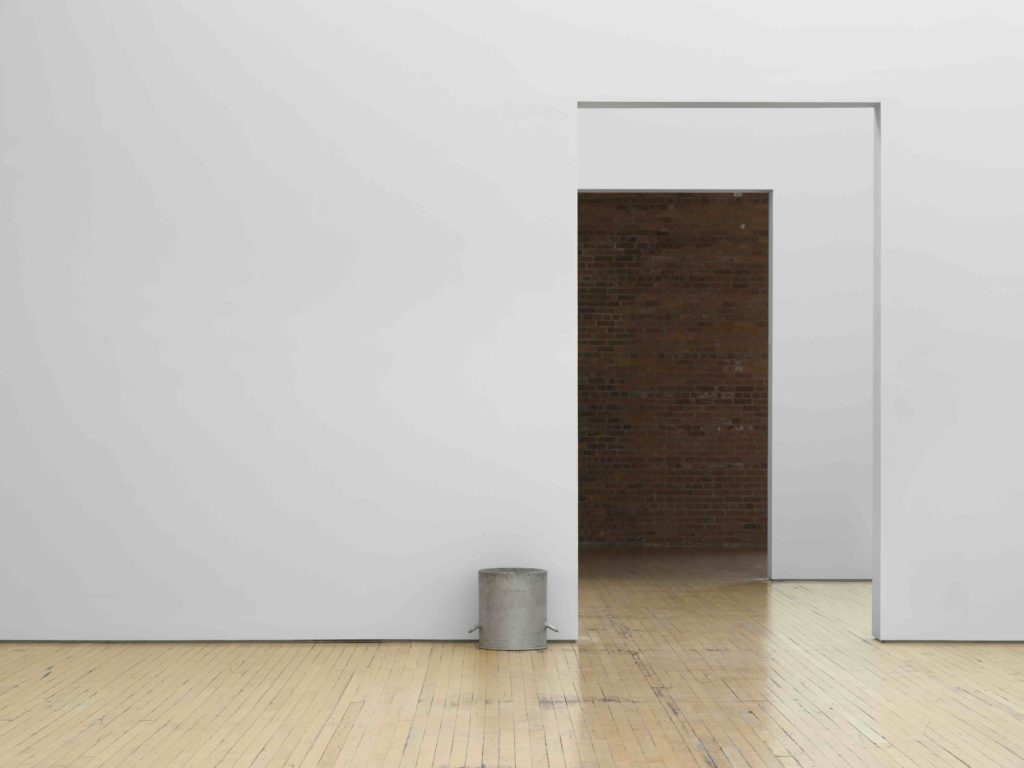

“Properties” is the title of Cameron Rowland’s exhibition at DiaBeacon. “Properties,” here, is used in the plural form. The exhibition unfolds as follows: the first room, built as an entry vestibule, serves as the context for the distribution of the exhibition pamphlet, written by the artist. At a glance, this room is about one-fifth the size of the room that follows. The pamphlets are stacked in threes on a bench placed on a wall to the left of the viewer. The rest of the room is empty. The adjacent room is used to display four elements: an overturned pot placed to the right of the entrance, against the side wall, followed by the structure of a bed, its head facing away from the viewer, and positioned in the center of the right wall, adjacent to five scythes placed in the middle of the left wall. Slightly to the left of the center of the back wall — offset from the viewer’s path, while on the same trajectory suggested by the entrance to the exhibition from the left, through the vestibule — a series of documents are arranged one after the other in two rows, under glass and framed. This arrangement — moving from the first point to the last — encourages an experience of each element as introducing and following the next; they are interrelated, forming a whole system.

[3] Harris, 279

[4] Harris, 280.

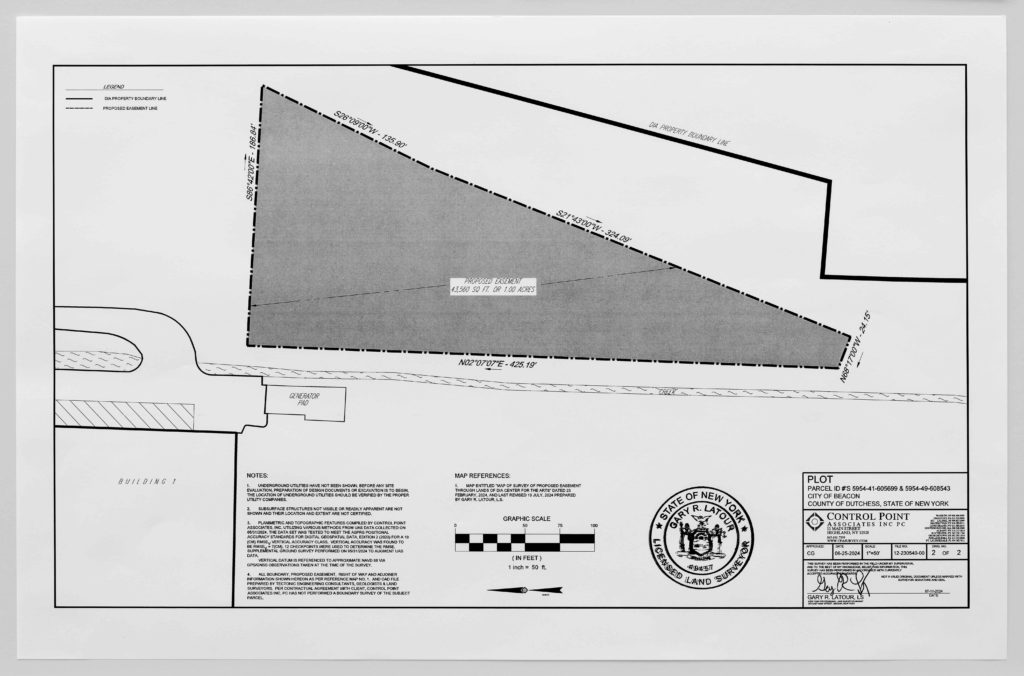

Cameron Rowland is an artist whose practice is concerned with examining the systems and methods through which institutions benefit from and perpetuate racial injustices. They employ a scope of elements — documents and objects, presented with a consciousness of their formal use and external to the artist’s own longevity, and thus forming territories— conducive to the complexity of historical racial systems, using both suggestive and referential considerations. These concepts are central to Rowland’s work, formally and conceptually engaging with systems and motifs of institutional critique to question not only the forms presented but also the spaces — equally territories — in which they exist. As such, “Properties” emerges from an understanding of the terrestrial condition implied on the very site of the Dia Foundation in upstate New York, a location built on land once owned by slave owners and traders from 1683 until the abolition of slavery in 1827. On this land, Black slaves were prohibited from being buried in cemeteries. This prohibition was a practice through which the degradation of Black bodies on the land of their enslavement was institutionalized. Rowland notes: “They were meant to make the degradation of blackness permanent. Black people were buried in unmarked slave plots and unregistered black burial grounds.”[5] The seminal work of the exhibition, Plot (2024), is thus constituted by the demarcation of one hectare of land occupied by the Foundation and ceded for the protection of potential graves of enslaved black individuals who may have been buried there. This supposition — in the tradition of the artist’s suggestive unveilings towards institutional degrees — structures the work by considering each plot of land as potentially containing the remains of former slaves. Visitors cannot directly access this specific land; however, they can understand it as a part of every other piece of land they traverse. No sign distinguishes the acre from other plots. It is forbidden to use, exploit, divide, or develop any future ambitions upon it; it is now land — thus, owned territory — for the enslaved whose bodies may rest there, and so are resting there.

[5] Cameron Rowland, Properties (Dia Art Foundation, 2024), 8.

In the context of slavery in the United States, Black enslaved people were regarded as integral elements of the land, and thus property of their masters to a similar degree, reduced to the status of commodities. The land, as a historical prison complex controlled by white masters, saw the Black body as an object akin to the goods it once embodied — commodity and non-subject — perpetuating itself even after the abolition of slavery. This land, within the grounds of DiaBeacon, now retributively marked, signifies a reversal of the system through which the enslaved Black subject lived and died upon it without autonomy or self-determination, their value entirely dependent on their productivity as slaves. In enacting this reversal, Rowland, as an artist, establishes a plan of inversion, aimed at restoring what was once denied.

Concepts of counterproductivity within Black experiences are central to Rowland’s work, which locates the collective Black consciousness around the potential embedded in each element of their forced condition as a tool for liberation. Collective refusal, here, and as a practice, is the result of this distinct collective consciousness involving the creation of systems that use every object within the awareness of the negative potential in their counter use. These objects (presented in the exhibition through the suggestion of their previous historical existence, and thus use) are no longer those of the masters, but those specifically tied to the condition of the enslaved. Underproduction (2024), a bucket placed upside down against the entrance wall, signifies this negation as a collective logic; the inverted pot blocking the sound emitted by the gathering of enslaved individuals — a collective act that was forbidden (enslaved people, being more numerous than their masters on the plantations, posed a threat if they became aware of their collective strength). Enslaved people were not permitted to leave the plantation, and they were reduced to the constant labor required of them on the land. Conjunctionally, several enslaved people used their scythes — used on the plantations for sharecropping — as tools of insurgence in Henrico County, Virginia in 1800; in Southampton County, Virginia in 1831; and in Coffeeville, Mississippi in 1858. As such, Commissary (2024), the disposal of five scythes arranged one after the other, undulating from the shape of the one that follows, are bodies conscious of their own counterproductivity potential–instruments of their autonomous and advancing resistance.

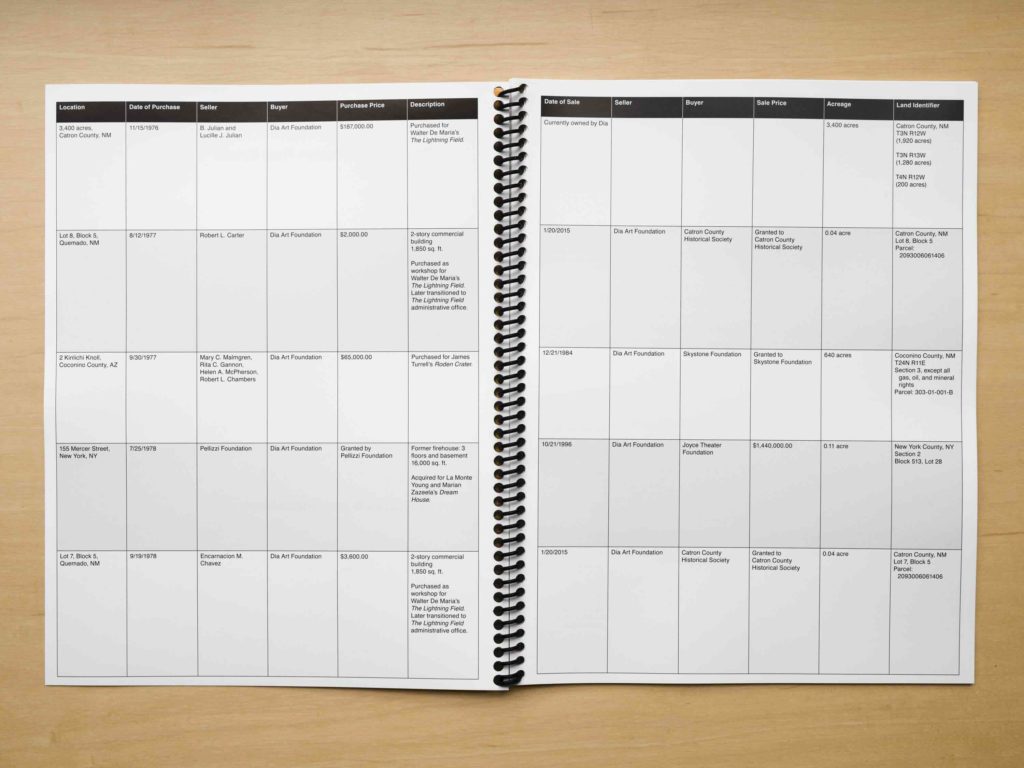

In 2018, Cameron Rowland implemented an extended loan regarding one acre of land on Edisto Island, South Carolina (Depreciation, 2018). Its origin stemmed from General William Tecumseh Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15, issued in January 1865, which granted forty acres and a mule as reparations to “negro families now freed,”[6] driven by the fear of a potential uprising by thousands of former enslaved individuals following his army. In 1865, approximately forty thousand former slaves settled on the land, only to be expelled the following year after the death of President Lincoln and the subsequent demand for the restitution of the land to former Confederate owners by President Andrew Johnson. In response, the freed slaves were offered the option to work for their former masters — now referred to as employers — or be forcibly removed. This expulsion exposed them to systematic arrests for “vagrancy,” and by 1870 most of the land was redistributed to former masters. In 2018, an acre of land within the former Edisto Island plantation was purchased as part of Rowland’s project through a company founded by the artist. The land was then registered under a restrictive covenant that prohibited any development on it, rendering it economically valueless. Similarly to Plot (2024), Depreciation (2018) was detached from the conventional understanding of property as a juridical-economic state associated with whiteness; it was stripped of its economic potential, existing solely as the context for an act of restitution. By refusing to work as laborers on this land in 1867, the former enslaved collectively negated the value of the land and, therefore, its status as property; they established a system in which the complex structures of their subjugation could be transformed into a framework for restitution, manifesting through the land’s negative form and counterproductivity potential.

Persistently building upon the collective formation of the Black mass, Cameron Rowland interrogates a consciousness linked to Black collective operations – from the time of slavery, through its abolition, and during each of its tacit attempts at reestablishment in modern societies — that has consistently deconstructed the very notion of property within a context of racial castes. It has nullified it, and continues to nullify it; “It runs below the index of history. It is property in rebellion.”[7]

[6] Headquarters, “Military Division of the Mississippi,” Special Field Orders No. 15, 1865.

[7] Rowland, Properties, 5.