Olivia van Kuiken once said: “A painting is incapable of telling time. It’s a static image.”[1]

That line keeps tolling in the background as her career advances in fits and riffs, like a clock that refuses the hour yet won’t stop humming. If painting can’t tick, then the body inside it must do the temporal work: multiplying limbs, gliding between frames. In van Kuiken’s story, time is not announced; it’s felt — through cuts, relays, and returns.

She begins as many painters do, with drawing not as rehearsal but as propulsion — scruffy marks that later are scaled up until a scribble becomes a tendon and a loop learns to breathe.

The early problem is legibility. She has said that, as a Cooper Union student, she set out to make paintings that “refused meaning” without switching of the viewer, asking how an image might let you in and still withhold a final verdict. She aims to create paths for the viewer to follow, routes that ultimately lead to a “no.” The “no” isn’t a negation so much as a discipline: a way of keeping the work alive to possibility rather than locked to a single moral.

The first public chapter arrives in July 2022, when King’s Leap presents “She clock, me clock, we clock.” The title lurches between pronouns like a baton, passing subjectivity from hand to hand. The press release points to Rhoda Kellogg’s schemas of children’s marks and Fernand Deligny’s movement-maps of non-verbal lives: two systems of drawing that sit outside literary narration.[2] Van Kuiken uses them not to illustrate theory but to pry painting away from its habit of telling stories too quickly. Language is displaced and then made newly audible, like a radio caught between stations.

In the show’s suite of works, black-and-white profiles branded Justine (2022) and Juliette (2022) answer Marquis de Sade — whose writing, infamous for its depictions of abject libertine fantasies, figures in van Kuiken’s paintings — with a cool refusal of fleshy fetish. Sade’s 1791 Justine and 1797 Juliette form the backbone of his literary project: two sisters divided by virtue and vice, where Justine’s moral faith meets relentless brutality and Juliette’s indulgence exposes the violence of pleasure itself. Van Kuiken’s interest lies less in shock than in the way language enacts her total vision of desire and control, pitting corporeal experience against the institutions that govern it. Mirror (2022) stacks three mirrors that promise return and deliver none. The writing around the show underlines her method: begin from a preexisting “logic,” then pressure it until legibility becomes provisional.[3]

A year later, Chapter NY stages “Make me Mulch!,” a title pitched between menace and metamorphosis. It arrives alongside New York’s legalization of human composting; the work folds that public fact into her private grammar, breaking down bodies into nutrients for new forms. She enlarges small scribbles into elastic, sinuous gestures that parody the heroic artist’s hand. Accuracy becomes a question rather than a promise: “What is needed to create an identifiable image and what are its associations?” the text asks.[4] The central triptych, Zig Zag Girl (Hodler, Woman on her Deathbed) (2020), lifts a nineteenth-century vigil into a three-panel slice-and-seam, part magic trick, part critique of the stagecraft that has so often divided women for spectators’ pleasure. There’s an untitled diptych derived from Unica Zürn’s 1991 The Trumpets of Jericho — two heads sharing a single ear, hand-painted “pixels” that look like a machine’s language done by breath and wrist.[5] The joke (and the argument) is that technology’s cleanliness curdles in paint: a pixel, once humanly made, can never be purely digital again.

By 2024, the vocabulary blooms and frays at once. Château Shatto’s “Beil Lieb” reads like a grammar book with its rules crossed out; her work suturing referential material within expressively constructed fields, with the paintings turning illusion into a physical condition rather than a simple perspectival trick. The press text returns to Zürn’s ecstatic architecture: a bounded tower under pressure, a skin that contains and constricts, a seam that won’t quite heal. In Düsseldorf at Caprii that year, the solo presentation “Losing looking leaving” and a scatter of group shows place her work in different atmospheres, where its temperature shifts: less imagistic, more experiential; the viewer’s body pulled into the choreography.

Then 2025, and “Bastard Rhyme” at Matthew Brown in New York: a show that treats language like a sparring partner and the gallery like a sentence diagram. The press text, written by Reilly Davidson, is explicit about her feud with stasis, pairing her interest in mobility with Eadweard Muybridge’s motion studies and Giacomo Balla’s leash-straining pup — a lineage in which repetition becomes the instrument for prising open time. Extremities multiply; figures are “subtly Frankensteined” from shuffled sources; the result is a verb disguised as a body.[6] Some works stand upright on the floor, two-sided: images in the round, their reverse faces carrying gorgeous monochromes like a secret parallel exhibition. The title itself crowns a head — BASTARD like a halo; RHYME murmur-pink at the lower edge — making the painting breathe letters the way a mouth exhales air.

It’s easy to narrate the timeline as gain, but that too would be a clock telling time. Better to think of these rooms as devices for experimenting with the conditions of looking: how to keep the viewer in the piece without assigning them a fixed seat. One of the through-lines, after all, is her obsession with what pictures can and can’t say. “I’m curious about the limits of language and symbolism,” she told Alex Leav for émergent; “When you uproot a symbol from its context, what does that say about a symbol’s ability to carry meaning? What does that say about language?”[7] Another: her allergy to a too-tidy finish — an aversion to paintings that feel overly clean. In her hands, mess becomes a strategy rather than a flaw, a method for shaking meaning loose.

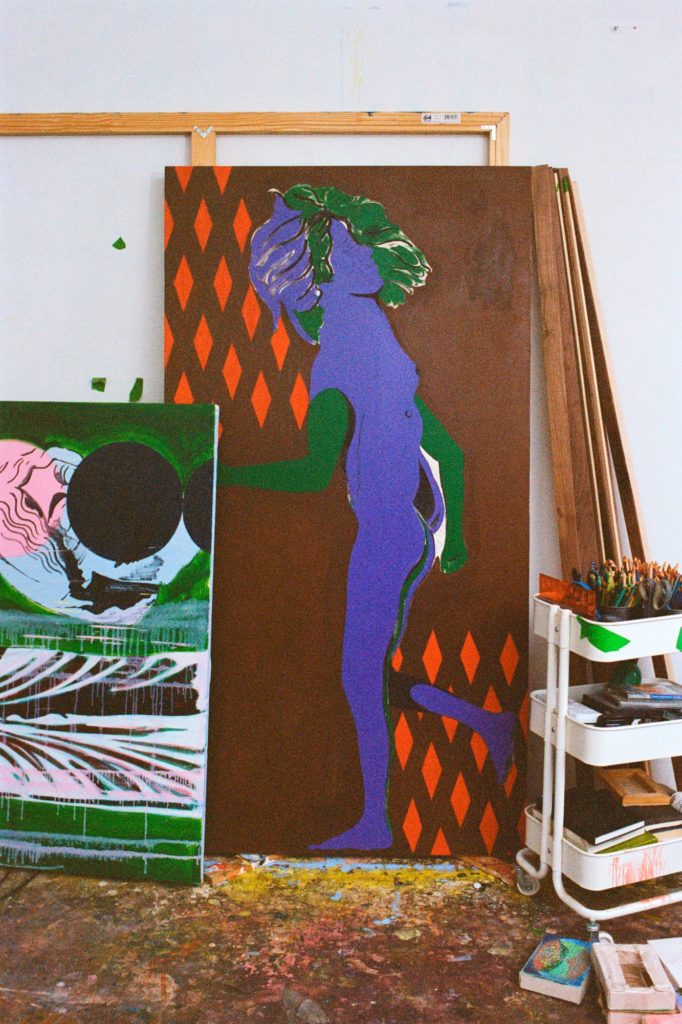

The studio is the place where these arguments are staged. A self-described studio rat, she is candid about the long, elastic days in that space — researching, drawing, staring — when painting is the least of it. She reads semiotics, builds an “archive of forms” from sites where language is pre- or post-verbal (children learning to speak, non-verbal communication, invented alphabets), and then lets the painting session become the attack: “Once I have the references set up, it’s total chaos.”[8] This is why the work toggles between sign and smudge, between a legible thing and the refusal to be about that thing. A hand-painted pixel is exactly that — labor and tremor — yet it borrows the authority of the machine, only to return it scuffed. Everything is done by hand, a deliberate refusal of the digital gloss that would smooth away and erase touch.

Her interviews in 2025 add another register — tone as portrait, method as confession. “My practice channels intensity and ‘too muchness’ — into painting, it’s where I can let it all out,” she told Kristina Deska Nikolić for Les Nouveaux Riches, speaking of a studio routine calibrated to the present tense: images tuned to 2025’s attention span, architecture designed so the canvases talk among themselves.[9] If the internet is the dominant room where most people now meet paintings, she doesn’t recoil from that fact; she composes with it. Screens reshape perception; the work leans into that reshaping rather than sulking about it.

Across these years, certain motifs return with different weather. Listening, for one. In the “Make me Mulch!” diptych after Zürn, two heads share a single ear: a funny, unsettling emblem of how subjects exchange organs — my listening becomes yours; your voice, mine. The painting is stitched from imperfect “pixels,” a shared cortex that won’t resolve to a single speaker. Cutting, for another. Zig Zag Girl’s three panels don’t reconcile; their seams stay bright and argumentative, an admission that some violences are structural (the frame does its part) and some theatrical (the magician’s saw) and that the picture, if it is honest, will leave the seam visible. Movement is the third: Balla’s blur, Muybridge’s doubled legs, Futurism’s insistence that bodies multiply as they move, updated here not as dogma but as technique — a way to smuggle time into painting without pretending it can tell time.

And then there is speech, which enters as text and exits as stain. In “Bastard Rhyme,” language doesn’t caption the image; it haunts it. Letters ring a head like a wreath; elsewhere, words drift to the frame’s edges, half-visible like a thought you almost have. The press writing around “Beil Lieb” calls it “abstraction’s supplication to language,” an odd, precise phrase for the give-and-take by which her pictures both hunger for words and spit them out.[10]

This isn’t fashion for theory’s sake; it’s an ethics of reading. She wants to make pictures that are neither illustrations of ideas nor passive objects onto which meaning is poured. They’re negotiations — between viewer and painting, sign and sense, the wish to know and the right not to be known.

Chronology helps only if you treat it like a loose spine. So, spine it is:

2019: she finishes at Cooper Union with a rulebook she’ll soon betray — no faces, no text, no figures — which is already a way of thinking with and against the academy.

2022: the King’s Leap debut writes her concerns large — language dislocated, subjectivity split and swapped, painting as the arena where meaning both forms and burns out. Sade drifts through as language rather than smut; Deligny as map for thought outside speech.

2023: at Chapter NY she links decomposition to form. The title’s compost becomes an operating metaphor for how figures lose personhood to become vehicles for ideas; how drawing’s marks are mulched into the canvases’ larger gestures; how an image feeds its successor.

2024: “Beil Lieb” and “Losing looking leaving” articulate architecture as problem and partner: the paintings generate their own referential systems, put pressure on their perimeters, and invite bodies to move among them. The texts around these shows matter — not as commandments but as the echo chamber where the pictures test their voice.

2025: “Bastard Rhyme” is the big swerve into the room. Eight canvases are staged upright on the floor, their backs flashing austere color fields, the fronts a pageant of multiplied limbs and slant rhymes. It is both maximalist and minimalist, baroque in appetite and strict in its internal rules.

Through all of it runs a quiet insistence on process as timekeeper. If a painting can’t tell time, it can still store duration. You see it in the drag of a brush, the hiccup where a pencil wobbles over linen, the “mess” that she protects against the reign of screen-clean images. You feel it when she speaks about the viewer’s path that ends in refusal — a choreography of looking that takes seconds or minutes, then denies the cheap satisfaction of a plot.[11] You hear it in the interviews, where the present tense is not avoided but tuned to: color and composition “calibrated to engage a 2025 viewer,” she says, a rare candor about the problem of contemporaneity.[12]

It’s tempting, finally, to cast her as an artist of language — semiotics, archives, invented scripts — and to leave it there. But what seems to me most characteristic is her stubborn attention to the body: bodies sliced, sutured, multiplied, emptied out, and handed over to us as proxies for thought. She has said that her figures are symbolic rather than personal, even ideally genderless; they “could be anyone, or no one,” a way of keeping attention on the relation between viewer and image rather than the myth of the painter-muse dyad.[13] In that sense, her career to date reads as an ethics of depiction: how to picture bodies without claiming them; how to write with paint without forcing a gloss.

Perhaps that’s what the opening sentence is guarding. “A painting is incapable of telling time” is not a lament. It’s a vow to keep painting’s differences intact. Clocks divide and decree; pictures accumulate and delay. What van Kuiken keeps pursuing, show by show, is a way to make that delay feel rich: to turn the seam into an event; to stage a joke whose punchline is a question; to ask a viewer to enter a scene and find that their own movement, their own decoding, is the time the painting keeps.

If you walk her timeline in order, you discover it won’t sit still. Each exhibition binds itself to an earlier one while undoing the knot: King’s Leap’s experiments with language return at Chapter NY as compost and at Château Shatto as pressure against borders; the Düsseldorf staging foreshadows the two-sided “Bastard Rhyme” panels; Zürn’s ear reappears as the ear of the room — how works overhear and answer each other. The shows are not steps up; they’re spirals around a center that keeps migrating.

Some painters promise clarity and deliver pretty fog. Van Kuiken does something riskier. She promises fog — opacity, refusal — and delivers an exacting clarity about what painting can and cannot do. She won’t let an image tell you the time. She will let it thicken time until you feel it in your legs as you circle a floor piece, in your eyes as they learn the habit of not knowing, in your hands as they half-reach (child-like, Deligny-like) for a sign that slips its referent. And if you wanted a final rule to govern the chronology, it might be this: each show looks back with a grin and carries forward a problem, so that the career reads less like a ladder and more like a sentence with clauses, subclauses, and the occasional necessary stutter.

The hum in these canvases isn’t the hour; it’s the insistence of looking. The hands in them aren’t on a dial; they’re multiplied and in motion. And the bodies? They’re ours, for a while, as we enter and exit, carrying the echo of a path that led us to the brink and then said, beautifully: no.

Artist: Olivia van Kuiken

Photographer: Ian Kenneth Bird

Creative Direction: Alessio Avventuroso

Head of Partnership: Nerea Echebarria

Production: Flash Art Studios

Shoes: New Balance

Location: Artist’s studio, New York City

[1] A. Leav, “In the studio with Olivia van Kuiken,” émergent magazine, October 2025, https://www.emergentmag.com/interviews/olivia-van-kuiken.

[2] “She clock, me clock, we clock,” King’s Leap press release, July 2022, https://www.kingsleapfinearts.com/exhibitions/she-clock-me-clock-we-clock.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Make me Mulch!” Chapter NY press release, February 2023, https://chapter-ny.com/exhibitions/make-me-mulch/press-release/.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Reilly Davidson, “Bastard Rhyme” Matthew Brown press release, September 2025, https://www.matthewbrowngallery.com/exhibitions/olivia-van-kuiken.

[7] A. Leav, “In the studio with Olivia van Kuiken.”

[8] Ibid.

[9] K. Nikolić, “Interview with Olivia van Kuiken,” Les Nouveaux Riches, September 17, 2025, https://www.les-nouveaux-riches.com/interview-with-olivia-van-kuiken/.

[10] Château Shatto, “Beil Lieb,” press release, February 2024, https://www.chateaushatto.com/exhibition/beil-lieb.

[11] A. Leav, “In the studio with Olivia van Kuiken.”

[12] Château Shatto, “Beil Lieb.”

[13] Ibid.