The female body, in all its potential fantastic proportions, obsesses Mika Rottenberg. Her eccentric videos have featured body builders, dancers, wrestlers, and porn models laboring in confined, assembly-line settings to manufacture unusual objects related to the body: fast-growing fingernails morph into cherries, perspiration becomes the scent for tissues, and, in the video Dough, the tears of an obese beauty cause dough to rise.

More recently, Rottenberg has abandoned her cramped studio in favor of the wide-open spaces of the natural world. Inspired by the story of the Sutherland Sisters, a 19th-century family of girls who displayed their extra long hair in a Barnum & Bailey performance and marketed their own hair growth formula (supposedly including mist collected at Niagara Falls), she worked with members of a present day long hair club to make the short trailer Chasing Waterfalls: The Rise and Fall of the Amazing Seven Sutherland Sisters (Part One). As winner of the inaugural Cartier Award, Rottenberg screened the video at the 2006 Frieze Art Fair, giving her audience a tantalizing glimpse of the related project on which she is now working.

Merrily Kerr: Your videos have been set in an enclosed space; now you’re working outdoors. What has that shift been like?

Mika Rottenberg: In past pieces like Dough, I built one part of the set at a time and worked individually with each actor. I wanted to see what I could do with limited space. Now, I’m interested in finding out what I can do with no spatial limits, so I’m building a set completely from scratch in the middle of the woods.

MK: How did you choose the location for your shoot?

MR: The actors in the trailer are part of a long hair lovers Internet club, and three of them live near one town in Central Florida. I actually wish I could write a sitcom about the RV park/ retirement community where I’m staying. People there have a lot of time on their hands, which makes them creative — they do things like have their own parades. The Boy Scouts are even going to help me behind the scenes. Thanks to a piece in Vanity Fair, I got permission from a local farmer to do whatever I want with a huge piece of land that includes a petting zoo that no one visits.

MK: Has your normal working process had to change?

MR: My process usually follows several distinct stages: I start with drawings, which come purely from my imagination; then I try to find people I want to work with; I build the set or sculptural environment; then work with the actors in the space, making a lot of set changes. Eventually, there are always moments over which I have less control, as when I introduced the dough in Dough. There’s gravity and you know it’s going to go down, but I don’t know how a person is going to behave. I try to keep the camera on all the time so I have hours and hours of footage, but often, the material I actually use is from moments when the actors forget the camera is on. My first thought for my current project was to mimic a reality TV show by creating a space — in this case, a functioning 19th-century farm — and asking the women to just be there for a week. The scenario, along with their bad acting, could really make it ridiculous and funny.

MK: Will there be similarities to your previous themes?

MR: Like my other videos, I want the whole story to revolve around cause and effect — presenting a problem and then solving it. It may be a poor farm and the women bad farmers. Something will break and that will trigger the next thing, a method that will promote the story and develop the characters. I’m thinking in an almost sculptural way and trying to have the story be more physical, because I can’t write dialogue!

I’m inspired to think of the farm as a giant Earthwork in the sense that it’s a zone for experimentation with earth. There are parallels between the incredible amount of labor that goes into farming and the routines the women adopt to care for their hair, such as brushing it daily for two hours. I spent this week trying to make a device that would convert the strokes of a hairbrush into an energy source that could power other things on the farm, though I’m not sure I’ll even use the device in the final version.

MK: You closely associate the women with nature, whether it’s being near a waterfall or on a farm.

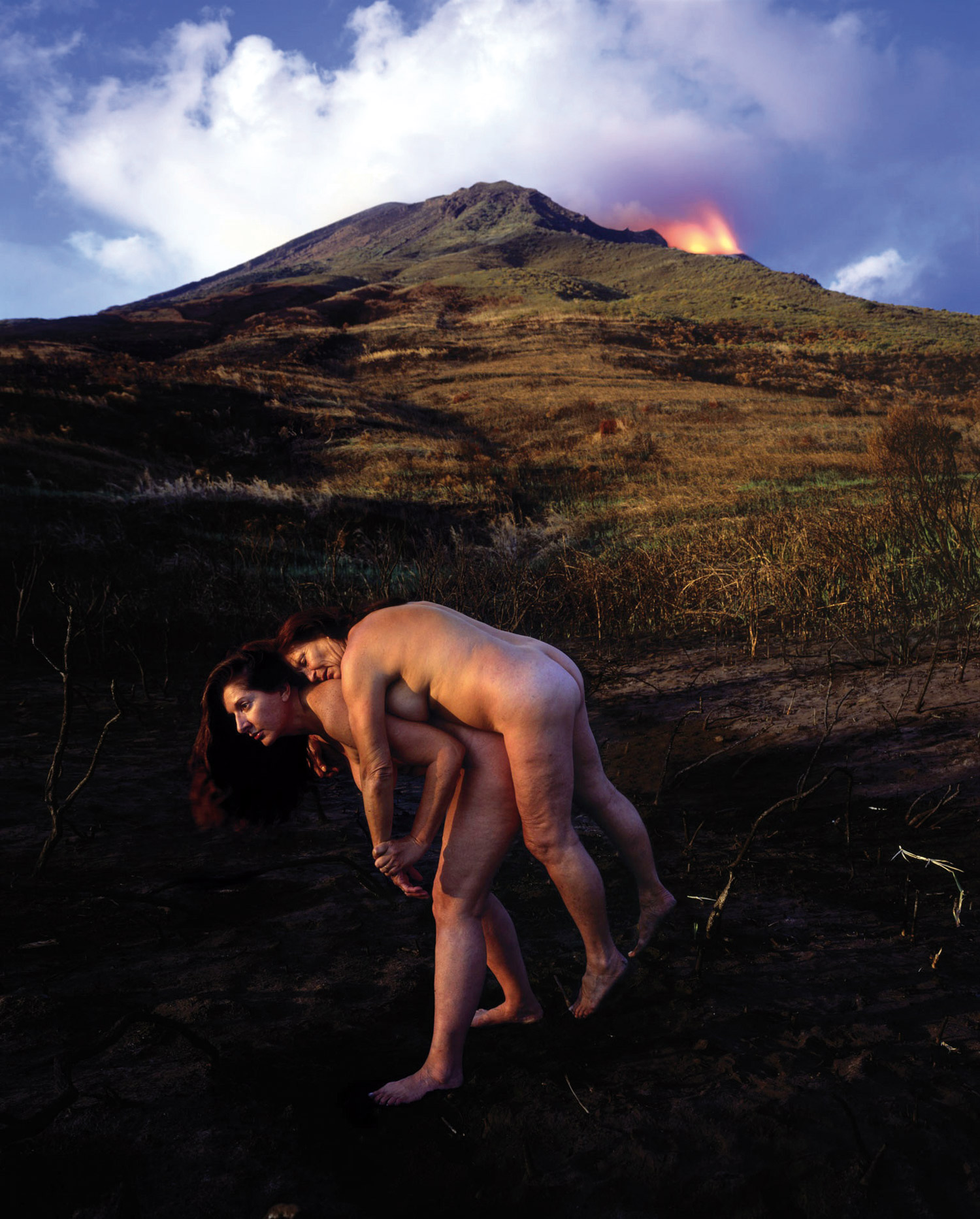

MR: My videos employ clichés about femininity, and this one involves associations between women, fertility and the earth. I’m attracted to how these trite ways of thinking about women offer a kind of bliss, that is, they satisfy a basic desire for resolution and simplicity. I’m a sucker for the related visual images — girls playing with little lambs and bunnies, waterfalls, and long blond hair blowing in the wind. But the fun really starts when I dissect the clichés, turning them inside out and showing them as they really are — creepy and uncanny. The Sutherland Sisters started selling their hair fertilizer as a result of the Industrial Revolution. They marketed their product right after chemical fertilizers for the soil came on the market, implying that if you could grow grass that much faster, then you could also grow hair. I like the contrast between male baldness and a super abundance of female hair.

MK: Certain aspects of the trailer remind me of a romance novel or soap opera.

MR: Absolutely, because it’s about entrepreneurs and new horizons. It blurs the line between cheesy, funny and genuine.

MK: Have you intentionally used humor in your past work?

MR: Whenever I try for it to be funny, it’s probably not, so I don’t. In Dough, there’s more of an awkward weirdness and element of grotesque that might come across as funny.

MK: That video seems to intentionally subvert conventional notions of beauty. The obese woman is pretty whereas the thin woman’s proportions are grotesque.

MR: I don’t know if I consciously think in terms of beauty or subverting beauty. My interest is more in things that the body produces and the way you use the body and it becomes more like an object. Some long-haired women relate to their hair like it’s a pet. The Sutherland Sisters were smart not to cut and sell their hair, but to keep it and use it as an object in their Barnum & Bailey act.

MK: Is your art about society’s response to their extremes?

MR: I don’t think it’s about society’s reaction to long hair or fat people. It’s about society’s interaction with the body in all its possibilities. Of course, there’s a layer that relates to American obesity, but that’s not my focus. Instead, it’s more about taking something to an extreme to examine it. If the dough is a stand-in for the body, there’s a fantasy about the body’s ability to stretch as if there’s nothing inside. And it’s also more about my personal attraction to long hair or to big bodies, for example. For my video Time and a Half I’d been looking on the Internet for someone with really long hair and then saw a woman on the subway. In that piece, I manipulated the background (a Chinese takeaway restaurant) by adding more palm trees to emphasize how the girl and her hair are so exotic.

MK: Could you be accused of exploiting your characters?

MR: I’m always waiting for that question. In a way, I am using the actors almost as objects, which is supposed to be a bad thing to do. I’m not trying to be a saint, and I don’t think the artist’s part is to be “the good guy.” I often feel uncomfortable in the position in which I put myself, but my connection with the actors runs like an experiment, a behavioral observation or a motion study. You could argue that we have an equal and satisfying relationship serving each other’s needs as exhibitionist and voyeur.

MK: Does your work come from a feminist perspective?

MR: I’ve always defined myself as a feminist. There is an aspect of misogyny in my work that is a response to the way society in general is. So I have to ask myself what it means to be a ‘good’ feminist. If I use people’s bodies and objectify them, then I’m a bad feminist, or I’m promoting the usual stereotypes. But since these are so common in daily life, it’s a way to negotiate or understand them and make them empowering. I keep questioning my own morality.

MK: There’s another -ism that relates to your work. Can you tell me about your references to Marxism?

MR: The very definition of labor is the process between a person and nature, but actually, I’m interested in Marx’s writing in an abstract way, as more poetic than political. The way he describes production and a person in motion is both beautiful and very visual. What’s inspiring to me is his way of measuring units of energy, materials and time involved in labor. Everyone assumes that in Dough there is an end product, but in my mind, the rising dough is constantly growing in volume so the excess that is pushed out is really more of a unit that measures work. The process of handling the dough also uses the forces of nature, like gravity, allergies and other reactions. In the new video, I’m growing crops and thinking of how to control the animals’ movement by harnessing their desire for food. It’s almost as if they’re the dough.

MK: What do the women in the long hair club think of reconnecting with nature?

MR: They’re each different but are all high maintenance. You have to be when you have hair that long. It gets delicate and they count every hair and split end. Most of the time it’s up, but when they take it down, it’s like a ceremony and their mobility can be almost paralyzed. But each has a unique relationship to her hair, and unlike my past videos only one of them makes a living (running a soft-porn website) from her unique feature. Very long hair is attractive to a lot of guys, but the women distinguish between the fetishists and the long-hair lovers. If they meet a man, he has to pass tests to make sure the attraction isn’t sexual, although, of course, it’s sexy.

MK: This sounds like a whole new way in which truth is stranger than fiction.

MR: Like my other videos, I’m setting up a situation and trusting reality to do the job. People might say that my work is absurd, but reality is even more so.