I

Sometimes making something leads to nothing. In 1997, Francis Alÿs spent nine hours pushing a block of ice through the streets of downtown Mexico City. The performance was documented by Rafael Ortega, his collaborator. Paradox of Praxis I, a five-minute video, is what remains. He begins in El Centro, in the same streets that three hundred years ago were canals that connected the Aztec city of Tenochtitlán with its temples and palaces. The ice, dragged and melting, leaves thin trails of water, memories of the lakes and canals that were once beneath the asphalt and concrete. By the time Alÿs and the block land in El Zócalo — the plaza built on top of what was once the ceremonial center of Tenochtitlán, and where today the Templo Mayor still pushes its way back up through the foundations — the block has shrunk to a cube. The artist smokes as the ice gets smaller and smaller. His hunched back becomes painful, and eventually he starts kicking the diminishing block across the volcanic rock pavers with his brown Converse All Stars. The trail evaporates and none of the water remains. Alÿs ends the video with three children looking at the last drops. They smile at the camera and wave.

Mexico City’s inciting incident is aquatic: Tenochtitlán was a small land mass connected by canals when seventeen horses arrived alongside Hernán Cortés in 1519, beasts so alien that Moctezuma, stoned on teonanácatl and weary of his own authority, invited them in with the focused curiosity of someone who is on mushrooms, euphoric and giggly. Seeing horses for the first time, their weight pounding the lakebed streets, Moctezuma allowed them to stay. The foreigners, arriving disoriented and psilocybined out of their minds by La Malinche, the mother of modern Mexico, saw a city on water, decapitated bodies hanging from El Templo Mayor. They saw an empire organized hydrologically, sustained by chinampas, aqueducts, and sluice gates, and decided to drain it. An ecological coup. Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec emperor, tortured with burning oil applied to his feet, told Cortés that all the gold had been thrown into the lakebed. Gold submerged, water hiding treasure. The horses became the transmutation device: from lake to land, from water to stone, from Huītzilōpōchtli and Tlaloc to linear colonial desire, from Tenochtitlán to Ciudad de México. Indigenous allies, persuaded or coerced, filled in their own sacred canals, destroyed their own bridges, cut the throat of their hydraulic empire as though a valley of lakes could ever be turned into solid ground. To “drain the swamp” is to declare ownership. Drainage is the infrastructure of control: a bureaucratic gesture that converts mystery into property. Water resists grids; it leaks, evaporates, floods, vanishes. It holds secrets. Land, on the other hand, can be measured, divided, bought, and sold. The Spaniards, exhausted from their watery expeditions, wanted plazas and straight medieval streets, stone underfoot rather than mud. They wanted the urbanism of Castile imposed on a lacustrine ecology they barely understood. So they began to redirect rivers, dig tunnels, and fill canals with rubble — often rubble made of temples and houses they themselves had destroyed. The crown wanted the lakes drained. The desagüe was entrusted to Enrico Martínez’s hands and, in 1607, the Huehuetoca tunnel collapsed repeatedly, a failure blamed on witchcraft rather than the limits of colonial engineering over an environment loaded with meaning for the indigenous. Still, the logic of desagüe hardened: tame the wild, eliminate the lakes, make a European city in the valley. Once these ideas were set, the ecological transformation of the valley was total. Mexico City grew not as an extension of its watery beginning but in opposition to it. The city began to dewater a wet reality. This ecological delusion, the colonial vampire in action, shapes the city. As the earth became thirsty for liquid, the infrastructure project kept filling it with rubble and later concrete. The construction of a modern city began on shaky ground.

Twenty-two million people live on a dried lakebed 2,200 meters above sea level, sustained by a fragile hydraulic system of pipes, trucks, and pumps. Water must travel two hundred kilometers and be lifted 2,000 meters to reach the valley; forty percent is lost through leaks, and only seven percent of the wastewater is treated. The aquifer beneath rumbles, the ground sinks by centimeters each year as colonial drainage meets neoliberal neglect. Whole neighborhoods kidnap water trucks to secure their supply. It is a city built of Rotoplas and five-gallon buckets, a bricolage of hoses, barrels, bribes, and hope. Mexico City is big, and so is its infrastructure — projects once meant to connect, join, and grow the metropolis have instead produced a decontextualized urbanism. A city seven thousand feet above the sea, and yet somehow it had a killer whale living there throughout my childhood. Keiko the whale became a crossover star as the leading lady in a major Hollywood franchise, just like Dolores del Río or Salma Hayek. The day she was removed from the city was a sad one. Streets overflowed with people, watching as the mass of a biological body that never should have been out of the ocean made its way back to sea level. The city was shaped as much by the Olympics as by the Tlatelolco massacre. The lacustrine beginnings of the city have disappeared as the climate erodes around us and foreigners reinterpret the place. The city continues as an ecological delusion. Looking for gold in all the wrong places. The sacrifices continue, this time staged not upon a pyramid but rather a tandeo on an asphalt flat filled with Infonavits.

II

The Aztec utopia was an island floating in the middle of Lago de Texcoco. By the mid- twentieth century, an imported ecological delusion had dried up the lake and the island became simply land. The city, sinking in its own absence of water, struggled to wet its inhabitants while depleting the springs of Xochimilco, Santa Fe, and Chapultepec. Just like their ancestors, they conjured and invoked distant waters, this time not through priests but through engineers. Under Manuel Ávila Camacho the plan was set in motion, and Miguel Alemán would inaugurate the Lerma System: a feat of dams, tunnels, and eleven pumping stations designed to reverse the course of a river. The Lerma basin lies sixty kilometers west, flowing away toward Lake Chapala, lower than Mexico City’s own altitude, so the water had to be captured at its highest springs in the Toluca Valley and then forced uphill through the volcanic wall of the Sierra de las Cruces. A river flow reversed. Only once over the divide could gravity carry it down into the basin. What began as aquifers and chinampas turned into electric pumps and concrete aqueducts. Mexico here becomes dependent on extracting water rather than harvesting its own, summoning rivers instead of tending lakes. While the communities close to the water source lost their water and agricultural irrigation power, the residents of Polanco and Pedregal turned on their taps and watered their gardens.

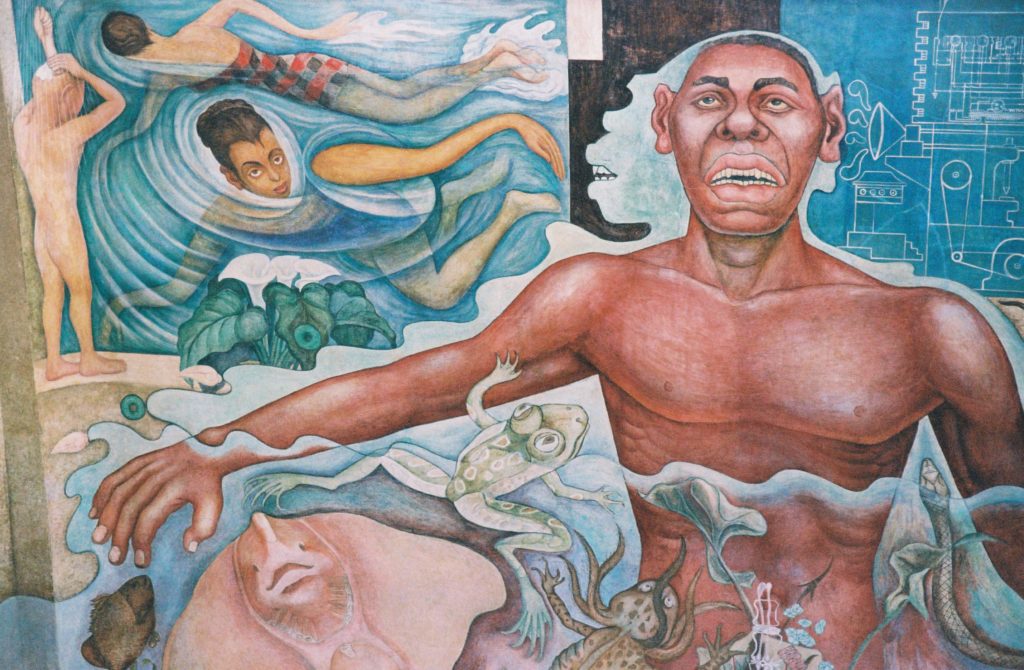

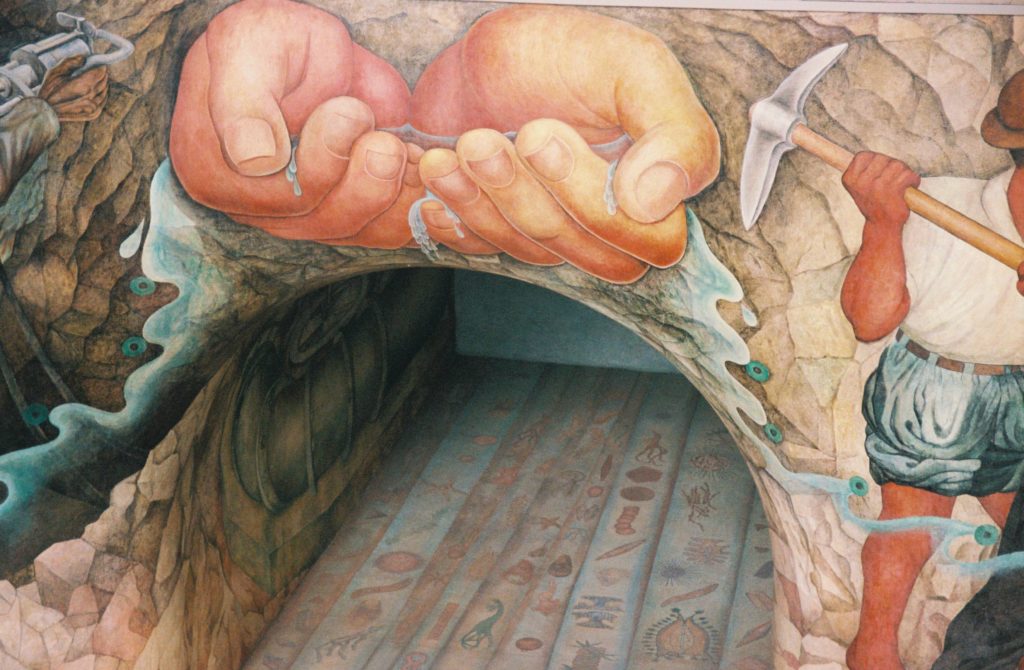

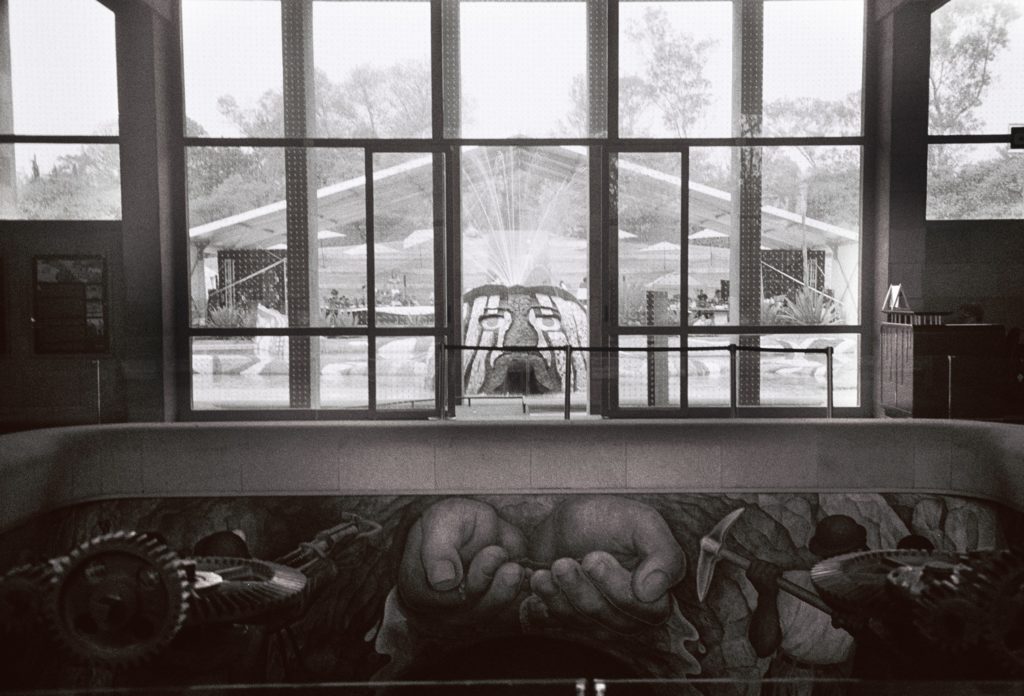

In 1951, to celebrate the engineering feat of the Lerma System, the Cárcamo de Dolores was designed by Ricardo Rivas in Chapultepec. This was the point where water from the Lerma River first entered the city, a hydraulic threshold turned into a temple. Rivas commissioned Diego Rivera to create a mural and fountain to crown the space, an allegory for the Sisyphean task of rerouting fluids and denying them from their rightful sources. Rivera’s El agua, origen de la vida covered the walls of the submerged chamber: a panorama of workers digging, carrying pipes, and laboring under the weight of infrastructure, while a bourgeois family sits at a table being served clean water, the fruits of others’ toil flowing neatly into their glasses. Rivera mixed a custom-pigmented polystyrene and sealed it with transparent rubber so the painting could survive constant immersion, an impossible fresco meant to live underwater.

It was an oxidized dream. The Cárcamo filled first with Lerma’s waters, brushing Rivera’s mural before flowing into the city’s pipes. Everyone in Mexico City was drinking Rivera, showering with water that had washed across his painted workers and the family they served, cleansing themselves with allegory. The symbolism was heavy-handed, necessary, a state-sponsored myth of progress. Outside, Rivera also designed a colossal sculpture of Tlaloc, the god of rain, monumental and archaic, echoing Juan O’Gorman’s prehispanic homages at UNAM. But the system failed almost immediately: cracks appeared, lime deposits accumulated, the mural’s aquatic immersion could not be sustained. Within a decade, the tank had to be emptied. Tlaloc, meant to preside over the eternal flow, stood instead as a dried ruin. The Cárcamo became less a piece of infrastructure than a monument to Mexico City’s ecological delusion — modernism’s promise of abundance collapsing into thirst, a temple to water that almost immediately failed.

III

I was living in Mexico City in the early days of 2016, right as the place was transitioning from DF (Federal District) to CDMX, a name that just doesn’t roll off my tongue as well as Peña Nieto thought it would. Se De Eme Equis. I was writing all day back then, and around 2 p.m. I would start ordering Mezcal with sal de gusano, and I would always get caught up thinking that the Aztecs must have felt the same hatred I was feeling when the Spaniards changed the name of their Tenochtitlán to Ciudad de Mexico. Anyway, after a few I would hit up Carlos, another architect from Mexico who had gone to the same school I had in London. Matos would then recommend Bosforo or some other bar to go to. In 2016, Airbnb and Uber were still novel ideas that carried some form of naive connection with them. The city was not yet gentrified; the number of international artistes that were calling the city their home was still low, like a young Berlin. Of course, there was always the shadow of Alÿs hanging around Covadonga, in the flag pole in El Zócalo. Muebles Sullivan was still open; I would sing “Querida” by Juan Gabriel underneath Barragán’s first apartment building in the city. I could write and drink all day because I had dressed the European windows for Diesel and Adidas that winter – I had twelve hundred pounds in my account and I would go to the barber weekly. I had to go to the dentist cause my teeth were aching, and I found one guy on Grindr who offered to fill my cavities for free in Masaryk. One night, after hanging out with Attilia, I ordered an Uber Black, and in comes a German Mexican street racer that I asked out on a date as we were waiting for the security guard to lift up the gate to my apartment. So he backed up and we ended up speeding through the Periférico. Dark ‘n’ stormy was his drink, we had three, more speed in some random house in Tacubaya. He was trying to explain to me how Mexico City’s morphology worked. I guess my eight-year stint in London had already made me into a foreigner. “See, it’s a diamond,” he said, again and again tracing the shape with his finger above an image of the Periférico on my iPhone screen. “Es un diamante y nunca sales de él.” Just like Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1962): the Periférico keeps you inside a bourgeois enclave while the outskirts are diamonds in the rough. So rough that water hardly penetrates these areas; delivery systems are trucks that have to be sent from water centers into the villages that have been swallowed by the city. Growing like a dried chinampa. An architecture of denial.

To gentrify is to drain. To erase memories and refill them with marketable surfaces. The anti-gentrification protests in the summer of 2025 in Mexico City — No es progreso, es despojo — are rooted in this original history. Just as canals were filled in for plazas, apartments are cleared for Airbnbs, neighborhoods repackaged as consumable diamonds. Just as Adonis in Luis Zapata Quiroz’s El vampiro de la colonia Roma (1979) isn’t just a sex worker drifting through Mexico City; he’s a figure for the way the city itself operates. His survival depends on flows — of money, of desire, of strangers coming and going — and the need to constantly disguise what’s actually happening. Mexico City works the same way. The whole desagüe system was designed to hide the fact that the valley is basically a drained lake. Instead of living with water, the city spends centuries forcing it underground, moving it somewhere else, pretending it isn’t there.

Tenochtitlán beneath Nueva España beneath DF beneath CDMX. The canals are not gone. They surface as protest routes, where Kate del Castillo meets with El Chapo’s men to talk to him on the phone, backdrops for Lady Gaga and M3GAN content. The Great Drainage Canal today runs with water three times more toxic than regulations allow, irrigating parsley, cilantro, cabbage, and lettuce in the Mezquital Valley, which then gets reintroduced into the city as food. Moctezuma’s revenge indeed: diarrhea as an ecological feedback loop. A place where every infrastructural collapse becomes cultural capital During the pandemic, Mexico City was TikTok’d into a global fetish. Americans moved in, seduced by cheap rent and restaurants under trees, repeating what Cortés did: arriving bewildered, filling voids with their own projections. Signs read: Fuera gringos. Glass storefronts were smashed. It was not simply xenophobia but an infrastructural memory surfacing: foreigners arrive, water disappears, land gets sold. In his 1950 work The Labyrinth of Solitude, Octavio Paz wrote about how the Mexican closes himself off because he doesn’t want to be water that spills but rather a wall that contains it. The city has become wall after wall: retaining walls, flood walls, bureaucratic walls. But water always seeps.

The wet dream turned dry. The foundations laid during that initial conquest gave the place an ethos. Get rid of the water. The original shame that domination always tries to conceal, which in this case was the encounter of a culture and religion that was richer, more complex, more plural than their own. They began to see the Aztec world as one full of potential threats that needed to be buried, removed, and dried up. The desire for conquest fueled by the shame of their inadequacies both at home and abroad created a perfect scenario for rampant violence and a reckless belief system imported with smallpox. How else can we explain the compulsion to repeat failed strategies, time after time, if not through shame. The city as a collection of decisions.

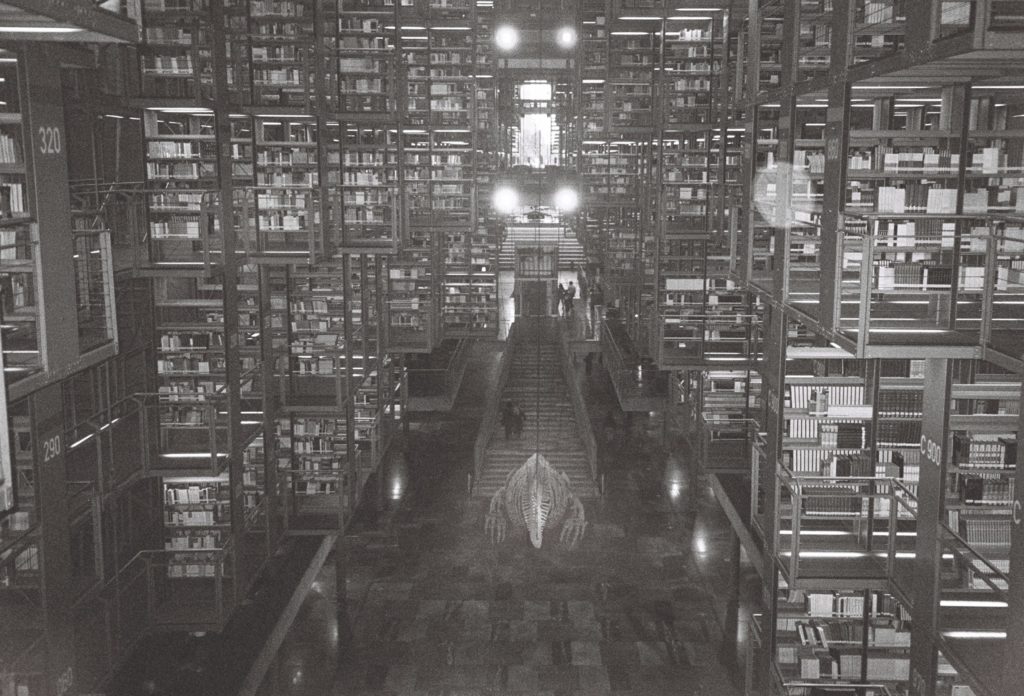

et there is a persistence to the pre-Hispanic world. The shaky foundations of the dried beds have begun to expunge the temples from underneath the ground, undermining the clean rationality of Catholicism; the Templo Mayor pushes the Cathedral at an angle, lopsided and cracking. Repressed histories keep resurfacing, either through Alÿs’s ice or Gabriel Orozco’s whale carcass in the Vasconcelos Library. Urban history is coded and exists in suspended time, at once dead and alive. Mexico City should not exist. Yet its liquidity is constantly there. Every earthquake anniversary, the simulacro sirens wail. Once, in a barber’s chair, a razor on my throat, I heard the siren and felt the floor plate sway in memory. Nothing moved, but the imagination of water returned: the city as liquid instability. The infrastructure of control is undone by its own tremor. Each drainage tunnel collapses, each aqueduct leaks, each mural cracks, each mega- project falters. And yet the city endures. Perhaps its identity is not stability but this constant oscillation between flood and drought, between excess and absence, and within that is a permanent reality that in some way manages to elude the action of time.

All images by Luis Ortega Govela.