“I would like to turn you inside out and step into your skin, to be that sober shadow in the mirror of indifference. Look at me, slowly, behold the irises wherein you hide, wherein lies the ultrasound of hidden, bleeding images. You shift. You shift and shift and shift because you know this is the last tomb of an invisible age of the dead. I would like to tell you things you know but never know, and because ours is the deep, scarred cataract of anguish, I would love you still in this age of hate and cholera.”

– excerpts taken from Remi Raji’s “Dreamtalk”

Ligia Lewis (b. 1983, Dominican Republic) begins her most recent production, minor matter (2016), with this omen, lines excerpted from Remi Raji’s poem “Dreamtalk.” Once her solemn voice evacuates the theater, the lights turn on achingly slowly, and the pounding of drums is the only adornment onstage; by the time the three bodies stiffly in parallel on the floor are revealed, the music has transitioned into a courtly Renaissance melody. They move fluidly between crisp poses and elegant, unhurried stretches, until they all land on their feet and find their way to each other to huddle momentarily before peeling away, only to conjoin again. This time, they slide between and over each other, moving together en masse. The sinister soundscape returns, and Lewis stands over, and places her foot on, the chest of another dancer, who lies listlessly on the floor.

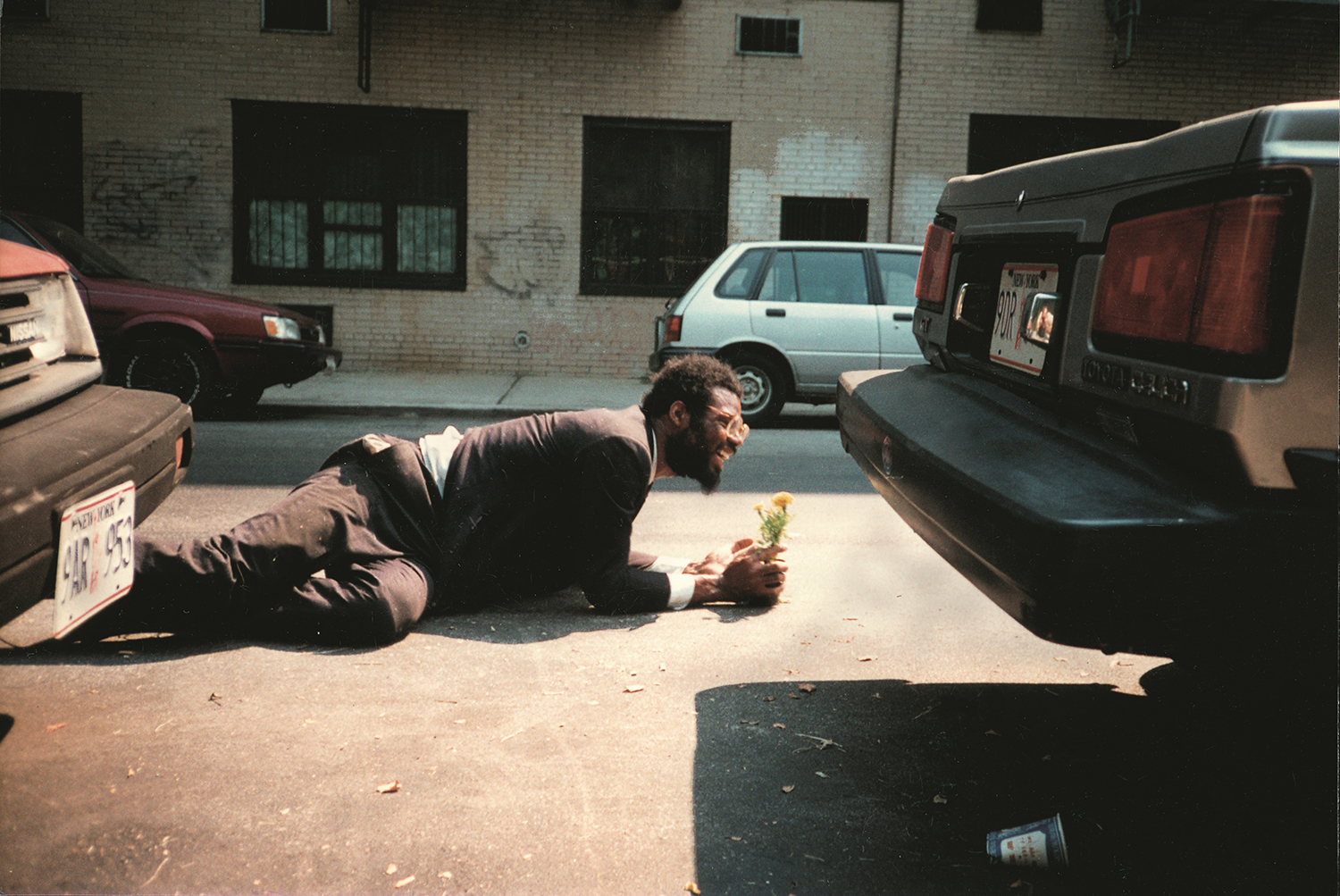

As quickly as the tableau is formed, it dissolves, into a transitory wrestling match; her opponent quickly taps out. Her match here is a male dancer, Tiran Willemse, though this detail should not be given any symptomatic weight: “I wasn’t interested in gender as a topic of discussion in this work — I wrestled as if there were no distinction [between us].”[1] Their emcee, dancer Jonathan Gonzalez, seems to be caught off guard: “I don’t feel like it’s all my problem, like, it can’t just be all my problem.” Walking to the front of the stage, addressing the audience like a stand-up comedian over dark, droning version of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607), long cord snaking from his microphone, his commentary drifts from the athletes on the ground behind him to success at large, to Nigel Farage and Donald Trump. The exhausted wrestler calls out an unambiguous “submit” in the background. “You gotta be quick on the feet, you gotta… be resilient,” continues our host, more to himself than anyone at his feet. “Make the choice to be an assertive bitch. You see, assertive bitches don’t make friends — they make enemies. But that’s OK. That’s OK. Cuz I’m not here for friends; I’m here for legacy.” His monologue devolves into drivel, and concludes with a concise, “This is Bitch 101. I’m your professor. Class is in session.” It’s the choreographer’s turn at soliloquy: pausing from fighting off an invisible aggressor and taking her turn at the mike, her voice is layered with a demonic filter, and she muses, “You know when all your emotions start to fill up inside of you, they start to spill over, it’s kind of… messy. And then somebody starts to be like, ‘That’s a lot.’ And you’re like, ‘Is that too much? Really? Cuz I just started… It’s not particular. Feelings matter. FEELINGS MATTER!’ It’s not a thing. It’s nothing.”

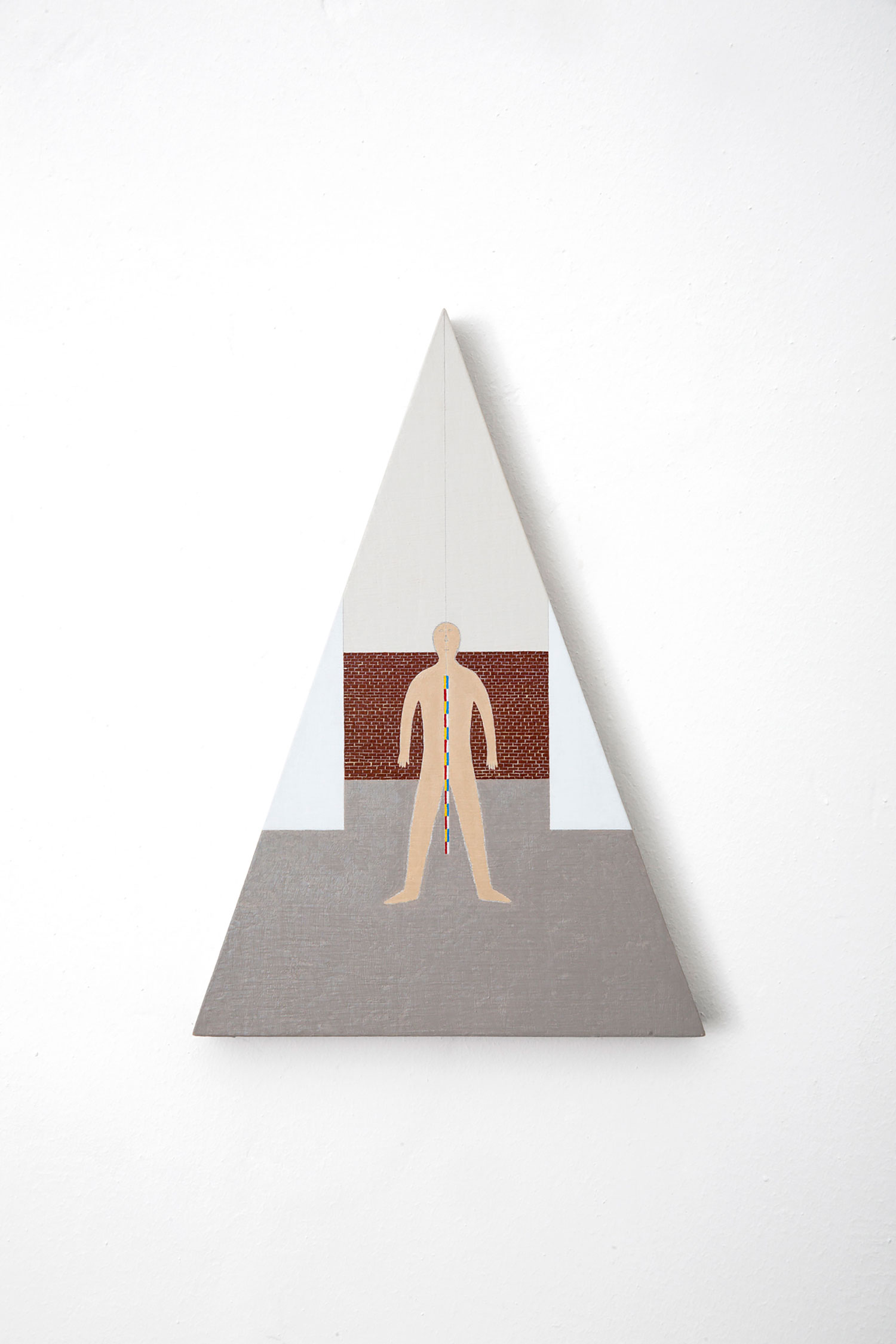

This snippet has a number of applications that would be appropriate in regard to the American, Berlin-based artist’s visual or aesthetic political standpoints, but the one that she draws on comes from Denise Ferreira da Silva’s “Toward a Black Feminist Poethics: The Quest(ion) of Blackness Towards the End of the World”: “The opening of the World as Plenum, where the subject figures without Time, stuck in an endless play of expression.” She explains, “transcribing this paradigm of the plenum — the whole of space regarded as being filled with matter — I use the black box in this manner.”[2]

Transcribing this paradigm of nothingness, Lewis has demurred in laying out explicitly the literary and artistic references of minor matter: “I know very few women and particularly women of color who can actually only make work and not have to explain it.” She shares that another text currently of much consequence in her practice is Hortense J. Spillers’s “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,”[3] offering an account of American slavery’s manipulation of African-American roles in the family model, and the subsequently evolved positions and directives of gender in these circumstances. Anonymity may be its own liberation. Discussing the materiality of race, she expands, “it represents nothing; it’s before gender, before culture, it’s just material and this is the way to get out of the intense racial discourse that we become trapped in.”

In the darkness behind her, fellow performers begin to swivel, an oblique physical quotation of Georges Perec’s writings on the use of space, specifically his Species of Spaces and Other Pieces (1974) — his experimental spatialization, treating the blankness of a page with the same abandon that one might use paint on a canvas. His disregard of printing convention gives the page sentience: his modest quote, “I write in the margin,” is itself rebellion, printed in the literal margin to the right of the text body; following many blank lines, at the bottom of the same page, he writes, “I start a new paragraph. I refer to a footnote.”[4] In front of us, the dancers occasionally pause in a tense first ballet position, fists out at either side, before gracefully opening to a wide second and sliding into a discrete fourth before lunging into third position. Lewis maintains their tight stature: “Left foot!”

A laser-focused light returns onto the stage, small enough to shine only on a single, exquisite, floating arm. Recalling the incoherent, detached mouth delivering her memoir of a long, cold and unremarkably dispassionate life in Samuel Beckett’s 1972 monologue Not I, the arm’s performance is accompanied by electronic musicians Carl Craig and Moritz von Oswald’s cover of Maurice Ravel’s classic Boléro (1928) mixed with Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition (1928).[5] Amending Maurice Béjart’s celebrated original 1960 ballet for Boléro, Lewis’s reworking waits for a few of the notoriously repetitive song’s movements, and then the house lights flood the arena, exposing again three autonomous solo performances, until they form a line again, stomping, stretching, and trotting in unison. “The piece is made between the distinction between the body and flesh and entanglement, so it’s three subjectivities. I had to write this as a trio,” she explains, “because I wanted to make something more complicated, to build on a logic of interdependence, and from there a certain kind of sociality emerges.” They jog in step, now stomping, clapping and jumping in a loose accord until they reach a breathless, brief conclusion, standing together at the stage’s end, one fist up, defiantly, the other over the heart. Spines arched to face the ceiling, staggering back to find each other’s grip, the trio collapses into a slow crawl on the floor. Thirty minutes in, the theater goes completely black, and Carl Craig’s techno chords are swept into the manic divergent synthesizers of Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” (1977). The pulsing disco hit quiets down, leading to an extended period of near-asphyxiating darkness — over five minutes.

As A$AP Rocky’s “L$D (LOVE x $EX x DREAMS)” (2015) seeps in, they settle into formation again, this time under red light. Forming a taut single line while lying on their sides, they become nearly indistinguishable under the transformative filter, simply becoming shapes and figures. “We literally became lines in space, we become part of the architecture, part of the fabric of the stage — a very humble relationship between black bodies on the black wall.” Recalling the influence of Merce Cunningham’s performances, she cites his commitment to the materiality of the body — “dance is dancing” — creating formal arrangements based on chance, and his collaborations with visual artists. As a dancer herself, she’s also toured and performed in the work of other choreographers, including productions by Mette Ingvartsen and Eszter Salamon, among others, before focusing on her own choreography in 2014. “Riffing off of some of Fred Moten’s thoughts on blackness, I chose the black box as a site from which blackness could be lived. I wanted to experiment with an endless unfolding of matter, morphing first from historical connotations and representations to after an hour arriving at a kind of nothingness, or bareness of the flesh, both of the theater’s and of the body’s. The last section is composed with the house lights up, so the literal fact of the black box and us are exposed.”

“I wanted to work with this problem of the black body, blackness, aesthetics, poetics, and allow for them to maybe fall outside of language because I think that there are also lots of possibilities there. The black body will remain a problem in a white world, and rather than trying to fix the problem [with my work], I try to continue to make more problems. My position, both political and aesthetic, will remain complicated. And I know the black body can never be fully abstracted — it has no neutral ground. But I won’t be held responsible for the failed politics of this reality. And the institution, which tends to be white when we’re talking about contemporary art practices, demands too much from a black artist, of doing the white institution’s political work [for them], when actually maybe black artists need to be supported so that they can continue creating complicated, interesting, and rich work that might be impossible to capture. I was happy to retreat into the black box, into a blackened world, even if only temporarily.”

The trio pulls themselves and each other up on their feet, a swarming knot of limbs and torsos, moving across the stage as a single, amorphous organism. Contracting and expanding, they use a wall as support to solidify their shape, becoming a stable, near-vertical line, moaning from the physical strain of maintaining this posture. Gently getting back on the ground, the red light bleeds into a bruise-violet. They are following their own directions again, running in place, uprocking, colliding, bouncing back like elastic from voguing death drops. The tempo quickens, and the lights flood. Circling arms, stepping backwards, miming hanging oneself and falling to the ground, colliding and collapsing with all their stamina. They congeal again in the center, and we can hear Lewis encouraging them — and perhaps herself, too — with an unsteady “hold, hold!” A couple more attempts at precarious, communal structure, leaning against a wall, until a final message, to the audience, to the house staff, to turn down the lights: “Black!” It’s not until they take their bow at the end that one notices that the trio is wearing sclera contact lenses, and their entire eyes are saturated an oily black — the cataracts of anguish she prepared us for in her first words to us.