In 2017, Gerhard Richter fulfilled his collectors’ deepest, darkest dream: he announced he was done with painting. That same year, he dragged his giant squeegee across canvas for the last time. It was a calculated move from a calculating man, whose mechanical approach to painting has only continued to climb in acclaim. Now, with his painting oeuvre declared complete, Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris offers a sweeping retrospective — one that feels both monumental and uneasy in its timing.

Richter is often touted as one of our greatest living painters. His work has struck a chord with our contemporary world, accustomed to image saturation and indifference. His goal of creating pictures of “nothing,” using technological methods of copying photographs or mechanically maneuvering the squeegee, gives rise to feelings that are familiar to those who consume conflict content and humor reels in quick succession: a worrying mix of anguish and apathy.

For this exhibition, Fondation Louis Vuitton offered all of its galleries to Richter. In return, he brought his own conditions, appointing Nicholas Serota and Dieter Schwarz — who co-curated his 2011 Tate retrospective — to lead the project. Their chronological hang unfolds in nine sections, from Table (1962), his self-declared “first painting,” to a series of drawings he completed as recently as last year.

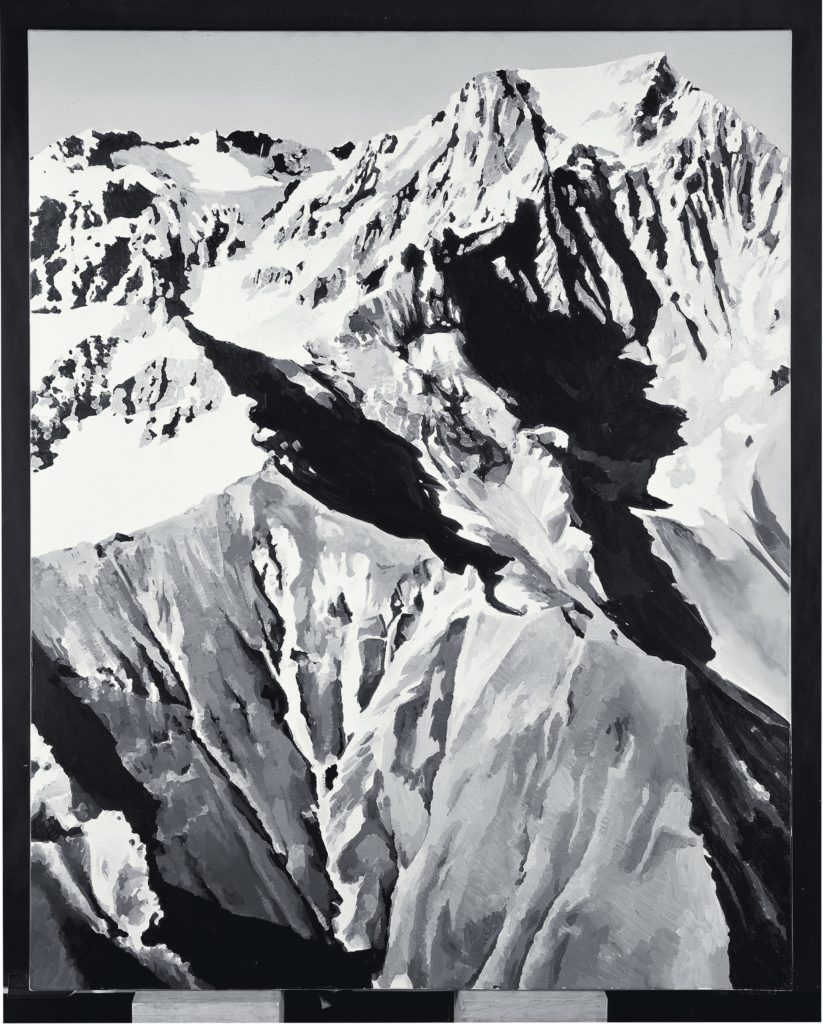

Each “gallery” summarizes more or less a decade of Richter’s production. The artist consistently oscillated between painting pictures of photographs and experimenting with chance-based processes like the squeegee and spatulas. This standardized curatorial approach works because Richter is a studio artist who viewed painting like an occupation, and investigated his artistic inquiries with the kind of repetition one might expect from an artisan.

Everything Richter does has a purpose. He has even wrested control over his oeuvre from the hands of art historians. Before Table, Richter had made several “informal” paintings, but this work is the starting hypothesis out of which everything else unfurls. Looking at the painting, one imagines the artist pushing and pulling his brush in frustration; a move akin to the artistic genius creating ex nihilo. Yet the apparently freeform defacement of the original image didn’t occur directly on the canvas at all. These dark, cloud-like streaks are actually a copy of the ink and solvent stains that had damaged the photograph Richter was working from.

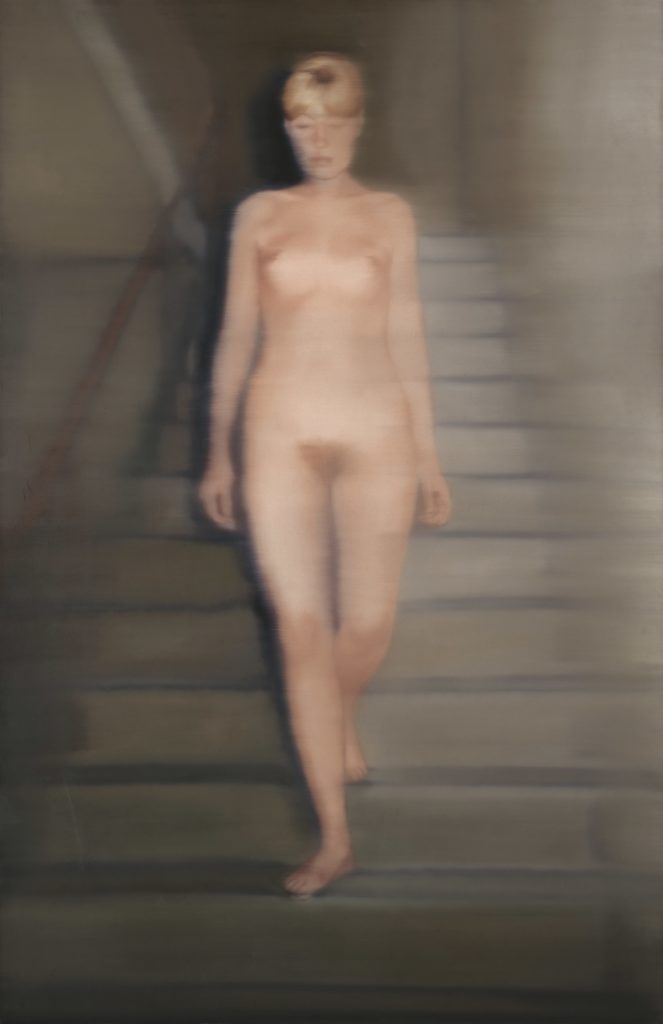

Richter never paints from direct observation. Every image is mediated — first through photography, and, later, through digital processes, as in the “Strip” series (2011), where constructed lines of color hypnotize and nauseate. Beyond his photo paintings, Richter remains in search of objective modes of painting in which the author is distant or erased completely. His “Grey” series (1974), composed of large monochromatic rectangles, communicates a visual language that is entirely inhuman. They feel a bit too close to home today, as generative AI floods us with strangely authorless images.

The guest curators write in the exhibition catalogue that “you immediately recognize a Richter painting, but you don’t recognize his hand.” Indeed, Richter’s imprint comes not from gesture but from choice.

His decision to paint two blurred black-and-white family portraits — one of his smiling Uncle Rudi (1965) in his soldier’s uniform, the other of his Aunt Marianne (1965) holding him as a child — seems, at first, arbitrary. But Uncle Rudi was a Nazi, and Aunt Marianne, who suffered from schizophrenia, was sterilized and murdered under the Aktion T4 euthanasia program designed to “purify” the German race. Richter’s process may well be detached, but his subject matter skewers significant contradictions of humanity.

Richter once said, “We’re always both: the state and the terrorist.” These squeamish dissonances are present in more ways than just the plastic, and while the exhibition echoes the Tate show’s curatorial approach, it comes to us in an entirely different context.

A clip from Richter’s 2011 documentary Gerhard Richter Painting went viral in the days before the opening of the exhibition. In it, the artist looks at his own paintings in a gallery and says, “Money is dirty.” Fondation Louis Vuitton is a private institution that was established in 2006 by Bernard Arnault, one of the richest men in the world. Arnault was under investigation over alleged money laundering in 2023, and last year, many who denounced the genocide in Palestine also called for a boycott of Arnault’s enterprises due to his investments in the Israeli cloud-based security company Wiz.

Richter’s work grapples with questions of erasure and messy personal and national histories, posed with a mechanical remove that actively invites intellectual distance and emotional ambiguity. In his foreword to the press kit, Arnault calls Richter “one of my favorite artists” and claims a connection to Richter’s approach that is akin to “a communion.” One has to ask: What does Richter’s ambiguity and distance mean in the context of Bernard Arnault’s art foundation?

Even if there are no easy answers, the question itself attests to the power of Richter’s work. If we find ourselves thinking — consciously or not — of the mass killing of Palestinian civilians while standing before the “Birkenau Paintings”(2014), that is up to us. Some might even ask how and why this is all still happening. At Fondation Louis Vuitton, Richter’s provocative indifference invites us to look at ourselves, and around us, for answers.