In the myth of Eros, the god of love and desire emerged from Chaos in the beginning of life itself in the form of an egg, glittering wings unfurling with an energy of attraction that brought structure to the cosmos. In The Agony of Eros (2012), theorist Byung-Chul Han laments how capitalism’s imperative toward self-optimization — to live better, faster, smoother — has become the new ordering principle, emptying the erotic of its essential vitality. For Han, the erotic is not transactional, or pornographic, or an object of romantic idealization, but an authentic encounter of almost transcendent love between self and other predicated on the condition of difference, or alterity. As he writes, “wherever the Other is missing, eros withers.”

New York-based artist Coco Klockner’s practice moves in these matrices of eroticism and longing between self and other, like electricity between human beings, or something akin to eros.

Through ambient sonic echoes and sound delays, gleaming adornments of pain and pleasure, or softly bruised surfaces of narratives that are never fully revealed, Klockner’s works reject idealized states of connection, instead searching for moments of both friction and intimacy. In doing so, she enacts how subjectivity is formed in tension with larger social infrastructures that compress selves into mythologies and mediated images that are also materially real. Her project is an ongoing negotiation of self in our moment of constant visibility as she navigates lived experiences specific to transfemininity ─ not reified or exalted or Eros godlike, or conceived as remedy for Han’s cisgendered, universalizing diagnosis of narcissistic love under neoliberalism, but as infinitely and achingly human. The resulting objects and installations, lush with materiality and pathos, exist as phenomenological currents of relationality where a deftly orchestrated gap in the legibility of a form, or air of unknowing, just might let eros persist.

In honesty (anti-cartesian model) (2023), a handsome “voice box” fashioned with apertures and contents abstracted from the eighteenth- century Wolfgang von Kempelen proto-artificial voice synthesizer that Klockner here renders non- functioning. Feared at the time for its artificial noises mysteriously produced from wood and leather, the silent speaking machine rhymes with the sculptor’s metallurgic casts of teeth channeling the carnivorous mouths of Ridley Scott’s 1979 Alien.

Rather than justifications for a work’s reason to exist (like a “provenance” intended to trace originals and “auras”), Klockner’s capacious yet pointed references approach sculpture “as though it were in transition,” as she has described, hovering in abstraction, non-utterance, and formal vernacular that sharply proves the artist’s observation that “trans women are much better at talking about form than art critics.” Threading redacted personal experience and associations through precisely sampled footnotes of social history, technology, and pop horror tropes, Klockner’s subtext exists as a visceral texture of unknowing that protects alterity and raises broader ontological questions that intentionally don’t resolve.

Good Name/Dead Name (2022), presented in Klockner’s solo exhibition “Sounding” (2022–23) at Silke Lindner, New York, is a deeply affective meditation on moving through the world as an artist and author. Like much of her published writing and cultural critique, Klockner’s sculptures often cull trans allegories from cisgendered narratives of authorship and aura with codes of masc and femme semiotics, here centered around Klockner’s retired brown hiking shoes tied with a ribbon frayed at the edges with a bittersweet acknowledgement that sometimes, the artist explains, self-actualization still isn’t enough for normative society’s acceptance. Charred and scorched with burn marks and rugged with age, dangling from the apparatus of a fractured music stand, the worn shoes might resemble a memorial; “Dead Name,” in the work’s title reflects a kind of passage over time in which transitioning, for some, is about past and reborn selves, while for others, it’s an ongoing “becoming.” But the worn shoes as proxy for the artist also seem to obliquely, but unmistakably, “crucify” Van Gogh’s Portrait of the Artist’s Shoes (1886), an iconic, cis- masculine symbolic self-portrait of authentic singular “interiority.” David Hammons famously riffed on the hallowed icon in Shoe Tree (1981), throwing sneakers over Richard Serra’s T.W.U. (1980) to “vandalize” the monument of “objective” neutrality of racialized structures. Klockner’s sly wit channels Hammons’s signature trickster institutional critique, but her quotations are communicated with irreconcilable affect. The sculpture’s small crumbling mounds of floor recall David Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (Face in Dirt) (1991), a mournful staged photograph of the artist’s face buried in the earth, made in anticipation of his premature death due to HIV/AIDS. This art-historical lineage circles around authors not as transcendent specters, or “mere” constructs, but as people whose lives are mediated by endless cultural images that reinforce institutional power like somatic memories stored in the gut.

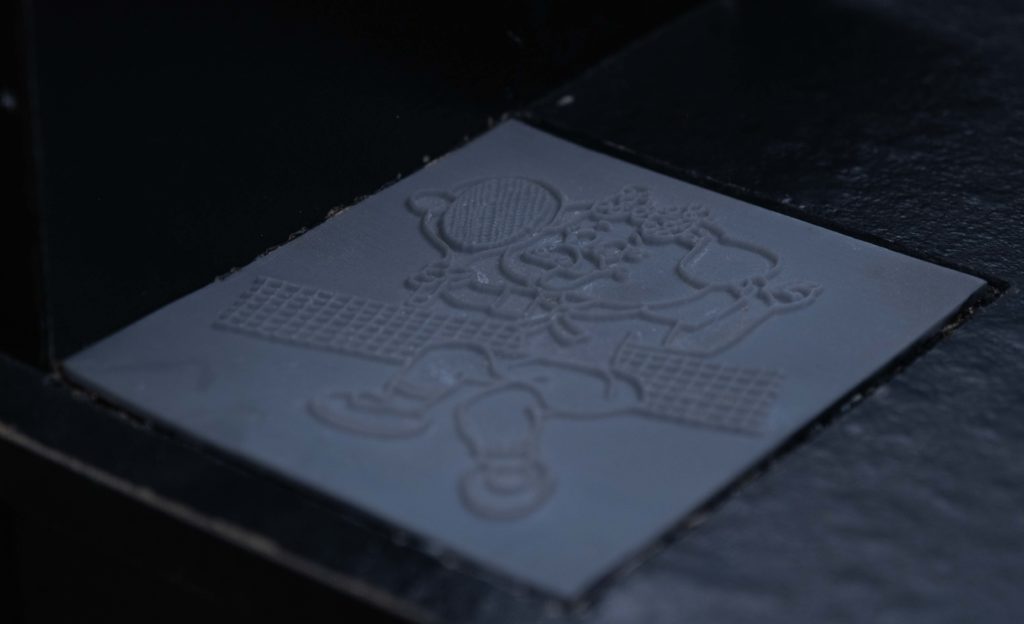

This kind of embodied image archive remind us that to take in Klockner’s practice as a whole, or a litany of references “about” transness, would contradict her works’ structural erotics. Casting glances and shadows rather than gazes, submerged in coy wordplay and demure double entendre and sultry atmospheres, her sculptures don’t see form as superficial; surface is depth. Or rather, a “libidinal vector,” a term she coined that uncannily rhymes with Lyotard’s “libidinal economy” of capitalist desire. But in her hands, libidinal is made literal by embracing surface appearances through adornment, fashion, and other external visual impressions that “anticipate desire and hope to activate it,” as she describes. In Rissa Exchange (2023), included in her first solo show, “Honesty” (2023) at Bad Water, Knoxville, a backpack landscaping sprayer is tenderly embroidered with a heart and cap reinforced with a puffy scrunchie, sweetly disclosed in the work’s material list as “scrunchie from Rissa received April 2023 in exchange for one brown scrunchie.” It’s an intimate annotation to the immense complexity of relational tending-to and love as both chemical and alchemical. Throughout her work, various markings are equally saccharine and clinical and sinister: cute doodles like casual stick-and-poke tattoos burned into industrial carpet in “brick ethic” (2024) at lower_cavity, Holyoke.

untitled (true love) (2024), also included in “brick ethic,” more solemnly addresses care (or lack thereof) in a dusty 90s-era first-aid kit fused to a black rectilinear steel armature, like cold industrial piping indicting a bureaucratic medical system that does not value all precious human life, instead categorizing bodies as objects to be “improved.” Importantly, Klockner’s works operate outside of a cisgendered assumption of body modification as a marker of inauthenticity. Cue the cultural obsession with superficial appearance as pop-horror satirized in recent movies like The Substance (2024) or The Materialists (2025), where a man undergoes surgery to break his own legs to gain six inches of “life-changing masculine value.” In contrast, Klockner’s cunning, theory- and pop-culture-inflected “metaphors and metonyms” lean away from absurd spectacle and toward a kind of flickering image through the objects and larger, sometimes cinematic atmospheres she builds as sculpture. Girl system 01 (Efficient Home Laptop Notebook Computer Desk with Square Shelves, Black/ Grey) (2024–25), a modular system of desks and shelves, lined with sculptures like bits of evidence, stages a quietly theatrical interrogation room with notes of Black Mirror surveillance and a psychic interior awareness of always being seen in our world where real life is often imagined as cinematic. Klockner returns to sculpture, she explains, and even to art at all, because it allows her to modulate a “high enough level of resolution and subtlety” such that nuance is still possible. To be perceived ─ or “clocked” ─ in Klockner’s work can elicit shame or intimacy or agency in one’s own awareness, evoking Gregg Bordowitz’s distinction between “I see you” and “I feel you.” Hovering in the exhibition’s shadows of partial sensing is the cultural and political shift from the urgency to be seen (in the realm of

representation) to the fear of potential violence (of forced disclosure) to a yearning for the embodied connection of being felt in the context of pervasive image culture. Is this eros?

In Girl-Sounding (Transpessimist Lovers) (2023), movement toward a more embodied relationality that subverts the overdetermining power of visual representation takes on a more explicitly erotic dimension in a soundscape-as- sculpture that reveals the ideological enclosures that delineate how voices move and are heard. The work’s centerpiece is a pair of tower speakers discreetly labeled with the words “good” and “girl.” Cast in custom metal nameplates in the font of a childhood hi-fi system, the text slips nostalgia into the BP-10 sound system, notably dated to the year of Klockner’s birth. Suggesting that that identity can be specific and anonymous, the sculpture asks whether we are all just recordings on a loop of outmoded technology. Or are we living entities with a racing, unmeasurable pulse? A sweetness ties together metrics and discipline with coquettish power dynamics in Sounding Rod (2022), a slender polished silver ribbon which references antique maritime tools once used to measure water depths, the eponymous BDSM object, and sentimental ornament. As systems seek to smooth, optimize, and control how identity is perceived through fixed labels, the artist reclaims surface as integral to self-fashioning and, in turn, self-determination. Both sensual and austere, mechanized and intimate, for Klockner, form and surface aren’t fetishized but held as essentially malleable.

These sculptural elements are part of a larger sonic sculpture, in which the gallery itself becomes a kind of larynx or voice box, and in which “the body” is not an anatomical vessel, but part of a larger structure of power flows and affects. As meta critique of these unseen audible frequencies, the gallery’s walls of commerce and institution reverberate with fragments of the artist’s vocal modulations in voice training, ambient soft impacts like whooshing arrows, and other elusive sonic traces of the room’s sound profile captured by a hidden microphone. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s call to let alterity speak on its own terms resonates, refusing monolithic representation as the theorist warned against power’s habit of speaking for marginalized subjects, rendering them voiceless. So does Mladen Dolar’s insight in A Voice and Nothing More (Short Circuits) (2008): the voice is never pure interiority but a threshold between body and language. Klockner’s upcoming SculptureCenter exhibition in New York will be similarly atmospheric and sonically dimensional, with recordings of voices perceived as if emanating through floorboards or drywall. Perhaps, it is these interstitial sculptural spaces, and Klockner’s between-the-lines reading of the world, that preserve erotic tension: the space between seeing and being seen, hearing and being heard, of moving toward someone or within oneself.

Returning to a lineage of authorship and aura, Klockner’s Egg I Laid (2023) is an ovular sculpture resembling an oversized delicate egg painted with a cream-colored surface. Here, Eros’s mythological ovoid birth cracks open a notion of metamorphosis as consciously existing on one’s own terms without resorting to creation stories of single-origin self as fetish object: Constantin Brâncuși’s The Newborn (1915)o f hidden interior truth, Sherrie Levine’s feminist appropriation CrystalNewborn (1993),andthetrans term for “not yet hatched.” In contrast to the phrase a “woman trapped in a man’s body” or vice versa, Klockner suggests that there is no “inner” truth as subjectivity. Klockner reveals that the self and flesh is as much surface and appearance as it is deeply felt memory and history. There is no “the body” — only bodies negotiating being.

Formlessness as structural critique has come to be seen as resistance to overdetermined meaning; but today, formlessness is the dominant condition with images seen and de-contextualized and thus easily subsumed. What if visual form isn’t inherently evil, or about control,but an abundant matrix of latent meanings that convey subjectivity as being with or in oramong, rather a static being? What if surface, as fashion, as ornamental flourish, as gleam and burn mark, can be a strategic method to surface (or hide and protect) the potential energy of precious relationality that cannot be co-opted? Is this not a structure of eros? Anne Carson’s line lingers: “Eros is a verb. It requires a leap, a desire, a reaching toward something not yet, or not fully, here.” In Klockner’s work, reaching toward the other is not to escape form and surface, but to find in it new conditions of possibility itself.