The first time I encountered Aki Goto’s work, it was received as a message from a friend during the summer of 2020, a season when days and exchanges melted into one another. I was on my phone a lot. In the video, posted on Instagram, Goto’s young children, Yuki and Senka, construct a small hut for an imaginary being at the base of a tree trunk from branches and flowers. A wistful Japanese pop ballad accompanies their building. Goto shot and edited it all on her phone. In another vignette, the kids run down a dirt road together, with Senka erupting in an unexpected tantrum. A dizzying electronic score and staccato edits provide the footage with a bracing rhythm. Goto’s voice drifts in and out, responding to her children’s queries or giving instructions.

These are hallucinatory, bucolic documentaries in miniature, accented with mothering. Shots of Senka in the backseat, her proud face adorned with self-applied make up, shift from joy to bewilderment and back again, all captured by Goto with discretion. Tales are told with unbridled excitement; tears are wiped away. The narratives never exceed one minute.

These early recordings picture fleeting moments of family life, made remarkable through Goto’s vigilant eye. In raw and honest captions to her posts, Goto characterized herself as loving, tired, gentle, angry, confused, apologetic. She was also very alert.

In writing about her compulsion to document her daughter in her early days of motherhood (in fact, right around the same time Goto embarked on making these videos) Leslie Jamison wrote, “My hunger for stimulation meant my gaze was sensitized, the way your eyes can see more after you’ve spent a few minutes in the dark.”[1] Motherhood was a catalyst for Goto’s offerings, and her expert editing and narrative construction pushed them beyond the classification of home movies.

This impulse to preserve presence remains essential to her art. In the same essay, Jamison expounds: “My own cell phone feeds it, this river — all the videos I’ve taken of my daughter during the first two years of her life, all the unrelenting and repetitive rhythms that feel necessary to capture because I know they’ll eventually be nothing but memories.”[2] Oases in ceaseless scrolls, the memories held by Goto and her family became mine.

[1] Leslie Jamison, “Other Voices, Other Rooms,” New York Review of Books, May 14, 2020.

[2] Ibid.

Born in Tokyo and raised in the Chiba prefecture, Goto began her creative endeavors developing textiles, designing garments, and composing songs. Working various day jobs, she drew and immersed herself in the city’s experimental music scene. In the early 2000s, she recorded tracks with collaborator Eiji Tominaga as the duo Mirin Mary. (Goto continues to make music as a member of the noise pop duo Masaaki.) At twenty-nine, she relocated from Tokyo to New York to work with artist and fashion designer Susan Cianciolo, whom she first met in 2004. Their collaborations would prove significant for Goto, whose move to the US prompted a total mind-body transformation. Immersed within the artistic currents of the city (“NY became my king,” she writes to me in an email), Goto existed in a complicated state of culture shock, admiration, and resentment toward a home country that she felt, at the time, left her unequipped to fully understand her new world. In an effort to reconcile these dissonant feelings, she and her partner, Kentaro Takashina, embarked on country-spanning road trips across the United States and Japan from 2010 to 2011, spending most of their time in rural locations.

As a result of these trips, Goto embraced theories of herbalism and permaculture, a practice of self-sustaining, holistic agriculture coined by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren in 1978 in response to industrialized farming methods. Goto was particularly inspired by the ways in which unmediated processes could yield a bounty. Without intervention, cycles of regeneration continue to precipitate beauty. Goto positioned herself as an observer of this phenomena, a spectator to grace. Her own fashion designs began incorporating natural materials sourced from her extensive travels. Her place in the universe as one living being among infinite other sources of life became paramount within her artistic practice. In 2012, Goto departed New York City to begin a life upstate with Takashina, to be immersed within nature and to live in an environment that would foster her burgeoning philosophies of art-making. With a deadpan self- awareness, Goto expresses to me in correspondence that “it wasn’t simple to make a simple life at all.”

Goto’s epiphanies and desire for greater connectedness with the natural world echo the tenets of American Transcendentalism, particularly the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson. In writing on nature in 1836, he notes, “Every moment instructs, and every object; for wisdom is infused into every form. It has been poured into us as blood; it convulsed us as pain; it slid into us as pleasure; it enveloped us in dull, melancholy days, or in days of cheerful labor; we did not guess its essence until after a long time.”[3] This conception of the world as a fully integrated matrix of knowledge and beauty, even in its most mundane corners, is central to Goto’s project.

Nature itself is a supporting character in her videos, providing a gentle, unobtrusive backdrop for her young protagonists to let their imaginations run free and their emotions surface with little interference. The lens of Goto’s iPhone camera is the Emersonian transparent eyeball, and the resulting footage teems with life: harmonious, fraught, a web of contradictions. Philosophical profundity often comes from her children.

In a recent video, I Love the Daffodils Too (2023), Goto follows Senka along a riverbed, with sunlight leaking in through treetops. She turns to her mother, who is holding the camera, and whispers, “Don’t be alive.” After a beat, she continues, “People will think that you’re alive, but it’s just actually your spirit.” Goto, bewildered and amused, seeks affirmation: “So I’m not alive, just my spirit.” Her daughter affirms. The stroll continues.

In November 2021, Goto presented an exhibition at C L E A R I N G’s Beverly Hills location titled “Sacred Shift.” Across the domestic gallery space, she presented her video vignettes, displayed on vertically oriented flat-screen monitors, alongside a body of textile work. Seventeen hanten, traditional Japanese kimono-style jackets often made of cotton, were presented in a towering arrangement above a fireplace. Devoid of their wearers, the jackets conjured a personless family portrait, a disappeared chorus.

[3] Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Nature,” in The Essential Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. Brooks Atkinson (New York: Modern Library, 2000), 377.

Goto has sewn hanten for decades, and their prominent presentation alongside her short videos prompts consideration of the relationship between sewing and film editing. Forging connections in time, with material, is second nature for Goto.

In 1895, Louis Lumière designed the Cinématographe, a film camera that could capture and project at sixteen frames per second, using intermittent movement based on that of the sewing machine. Deemed “feminine” from cinema’s earliest days, cutting and splicing film reels, considered tedious work akin to sewing and mending, was often delegated to women.

Yet this classification created opportunities for women to initiate and shape experiments in early filmmaking. An early force in this field, and an artistic forebear to Goto, is Elizaveta Svilova, editor of her husband Dziga Vertov’s groundbreaking films and a vital member of his Kino-Eye group. A heavy edit can make a film feel more like life itself, and we see that at work in Goto’s videos, which, though still present on Instagram, are now exhibited in galleries and theaters.[4] The physical task of splicing together a filmic montage is ever rarer, but the digital sensitivities demonstrated by Goto as she links moments into narrative evince a precision similar to that of a master tailor. Rather than a body, the seams of these videos envelop existence.

I am reminded of Wim Wenders’s 1989 documentary Notebooks On Cities and Clothes, a contemplative observation of fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto. In describing Yamamoto and his craft, Wenders posits that the designer “find[s] the essence of the thing in the process of fabricating it.” At the onset of new photographic technologies, Wenders asks his audience who the digital craftsman of the future might be. How might craft merge with haptics? How can essence be found in process today?

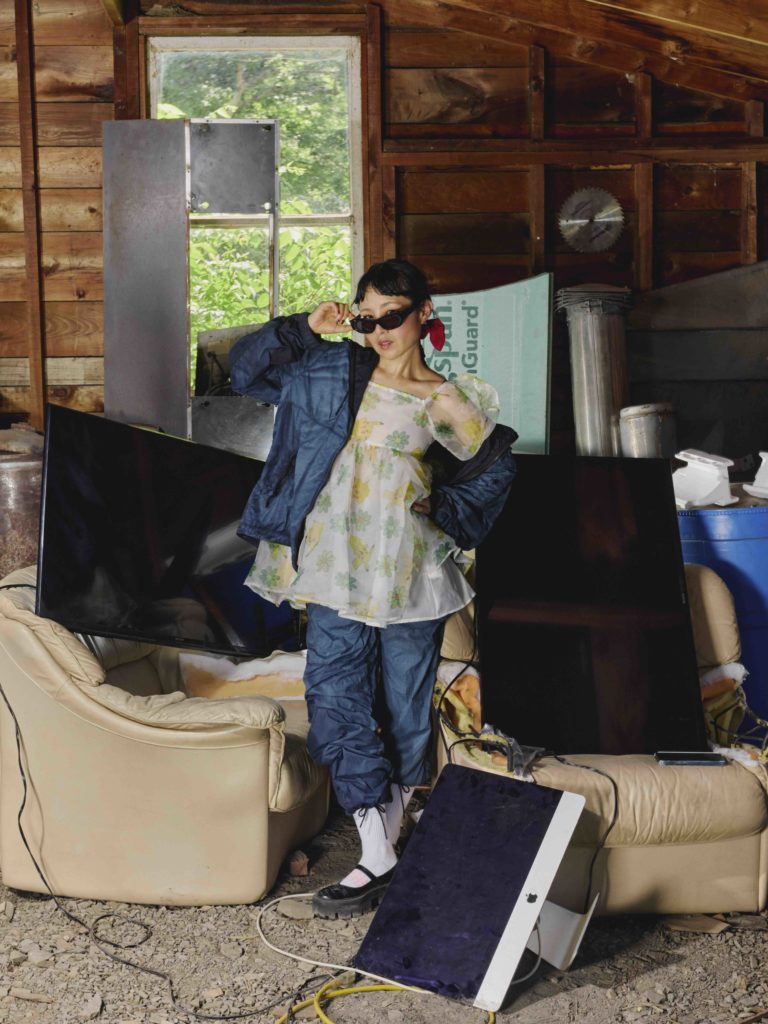

Goto provides a potential model for how core truths might be yielded from tools bent toward deception. But this body of work will shift as her family grows. Goto’s children are older now, and consciousness around the complexities of their subjecthood have deepened. Yuki, ten, is more camera shy. Senka, eight, is a more avid performer, but with age comes apprehension. In “Eyes on Shine” (2025), Goto’s most recent solo exhibition at New York’s Europa gallery, she presented God Amused (2025), a thirteen-minute travelogue that maps the journey of Goto’s family back to Japan to celebrate Shichi-Go-San, a traditional rite of passage celebrating good fortune for three- and seven-year-old girls, and five- and three-year-old boys. Interspersed with shots of her family lounging in a living room, an unforgettable perky poodle and street scenes from Japan, young Senka is shown getting made up for a photoshoot with her family. Cuteness abounds.

[4] On May 22, 2025, I organized “Somebody’s Children,” a screening of Goto’s videos at Roxy Theater in New York City on the occasion of her exhibition “Eyes on Shine” at Europa. That evening, her work was placed in dialogue with that of Sadie Benning, Ryan Trecartin, and Josiane M. H. Pozi, each of whom present varied depictions of youth in their moving-image work.

Sianne Ngai’s pioneering scholarship on the aesthetic potency of cute notes the ways in which it can generate an “oscillation between domination and passivity, or cruelty and tenderness.”[5] This constant shifting reflects Goto’s depictions of motherhood, where an expression of joy is followed by a sudden outburst of rage, where understandings of control crumble in an instant. Ngai continues, “Art has the capacity not only to reflect and mystify power but also to reflect on and make use of powerlessness.”[6] Goto is unafraid of surrender. When asked by the New York-based nonprofit Artists and Mothers the best advice she received as a mother, she replied: “There is no meaning in this universe.” Searching for sense and logic in this world is a fool’s errand for Goto, whose evolving artistic practice is unified by an uncommon openness to forces beyond the self, forces with which she strives to remain in flow. Is this life? I think back to Senka’s instructions: “Don’t be alive.”

[5] Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (Harvard University Press, 2012), 108.

[6] Ibid, 109.