It’s difficult to pinpoint where Anna Clegg’s paintings first appeared. Maybe it was online, or in a basement gallery in London. Memory is unreliable. It moves like heat on tarmac, warping whatever stays still for too long. What seems certain is that, upon seeing one of her works, there is a dual sensation: recognition and confusion. A moment of uncanny déjà-vu — without a clear source. There is a kind of false recognition in her works that leaves viewers quietly unsettled — like recalling a dream never had, or absorbing someone else’s memory as if it were personal. The paintings haunt in an anti-spectacular way. Not as ghosts, but as the residue of memories passed between people, blurred over time, retold until the origin fades.

In “Stainless,” her 2024 solo exhibition at Soup Gallery in London, Clegg wrote the accompanying text herself — a diaristic confession about cheating on school tests. The classroom is described not just as a setting, but as a tool and co-conspirator. Desks, windows, teacher’s backs — each detail collaborates in the act. There’s no guilt. She was a good student. The text reads with the precision of something remembered vividly, yet with each line comes the creeping question: Is any of this true? Clegg later admitted the story wasn’t. What felt autobiographical was collaged from fragments — stitched together to simulate memory. The final scene (with the teacher) was entirely fictional. “Even though I had it noted as a real memory,” she said, “I realized only days before the show that I’d misremembered the whole thing.” Her way of writing mirrors her painting: reassembling found things to simulate emotion.

Virginia Woolf once wrote, in Moments of Being (published posthumously in 1972), that “the past only comes back when the present runs so smoothly that it is like the sliding surface of a deep river. Then one sees through the surface to the depths.”[1] Clegg’s work seems to operate in a similar way — producing surfaces so glassy and smooth that something beneath begins to shimmer. The text doesn’t simply accompany the paintings; it infects them, or it’s infected by them. The written element acts as a counterweight to the hyper-clarity of the images, creating a tension — between image and word, fact and fabrication, the seen and the said. As Clegg puts it, she included writing in “Stainless” to offset the clarity of the paintings — to “open up a different register of viewing: an emotional or literary register as opposed to only visual.” There’s also a quiet mischief in these paintings — inviting the viewer to trust what they’re seeing, then undermining it. Clegg said she’s interested in how “specificity can become slippery,” and her work often uses real things — desks, receipts, film frames — not to document, but to erode the certainty of documentation itself.

[1] Virginia Woolf, Moments of Being: A Collection of Autobiographical Writing (New York: Harvest Books, 1985), 72.

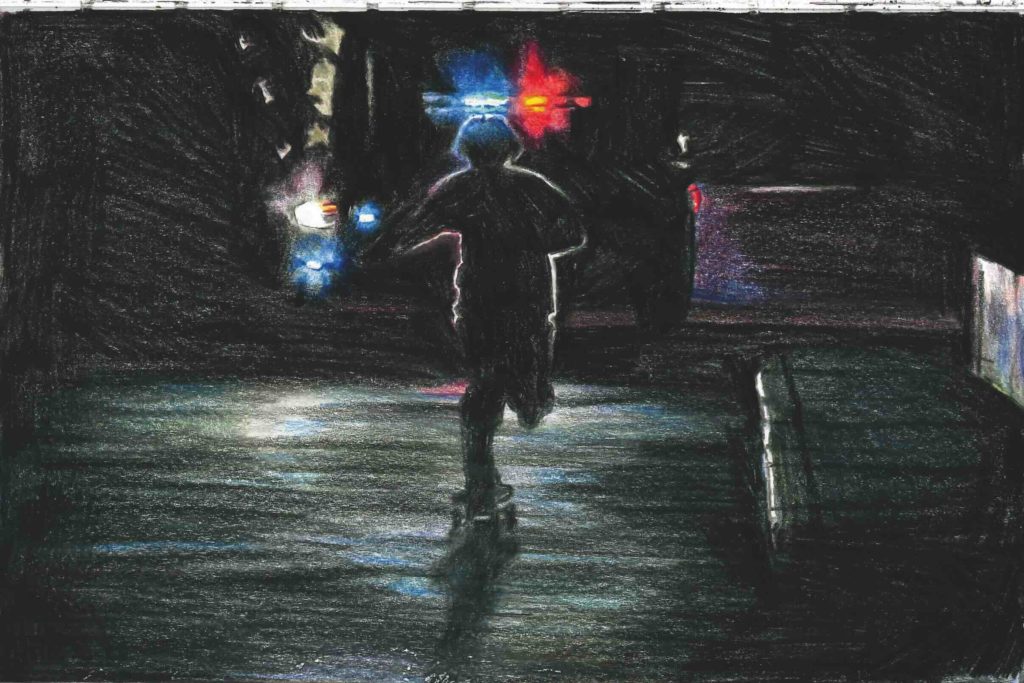

In that same text, the memory of classroom cheating slips into another — about using free editing software to stitch together a video from found footage: a skateboarder in Italy, 2006. The video is passed off by the narrating voice as original to her art teacher. In response, the teacher offers a memory of their own — a visit to a museum in Berlin a long time ago, tears in front of a Rembrandt painting — all while quietly seeing through the lie without making any accusation. A web of borrowed, half- true memories begins to form. One person’s lie becomes another’s truth. One detail — a tear, a skateboard, a desk — remains. Everything else dissolves.

What’s interesting isn’t just the lie, but how casually it becomes collective. Like a memory passed around a room until no one remembers where it started. There’s something viral in the way she constructs these anecdotes — sticky, iterative. They don’t build a punch line, they just kind of accumulate. There’s a very contemporary texture to that. Like scrolling through someone else’s private notes app. The entries feel deliberately unshaped. No hierarchy of importance, which is maybe how memory actually works.

The paintings in “Stainless” resemble diary entries from the middle of the day — neither climatic nor tragic. Instead: fragments of ordinary interiors, kitchen corners, record sleeves, anonymous portraits. On first glance, they appear as mundane snapshots, phone-camera casual. They hover between recognition and opacity. Familiar yet distinct. A viewer might ask: Do I know this place? Is this memory mine?

Clegg has described her own practice as an “accumulation of misalignments,” suggesting an interest not in getting things right, but in what happens when they slightly miss.

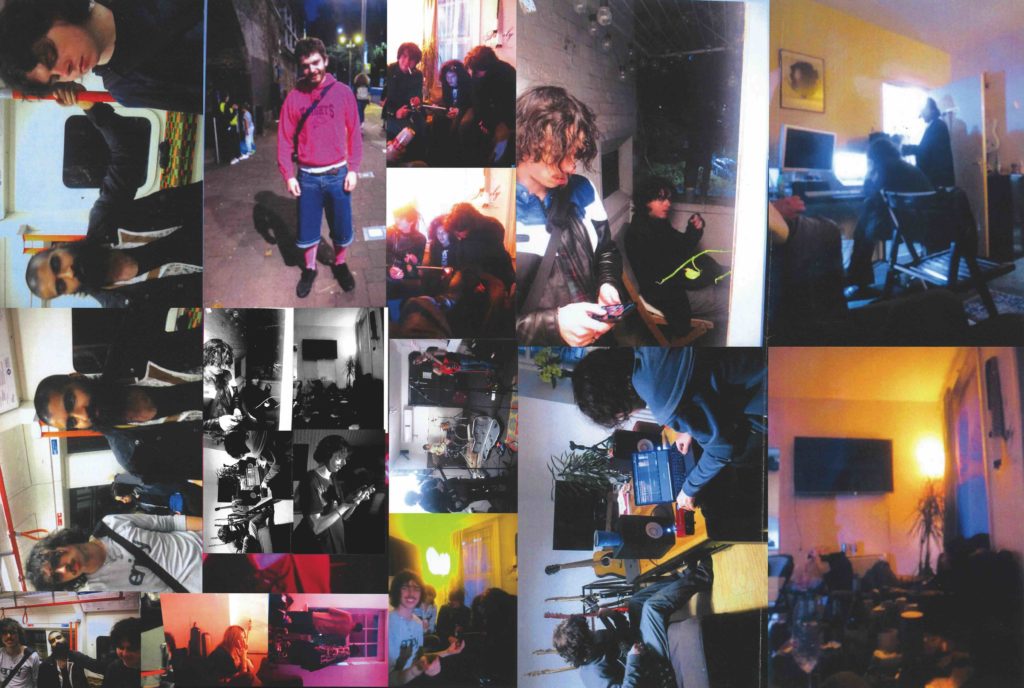

A similar atmosphere surfaces in “Blonde Redhead” (2024) at Painters Painting Paintings in London, where Clegg showed a series of paintings made during her move into a new flat in London. The works document moments of transition — cardboard boxes, half-assembled furniture, a guitar leaning against a bare wall, a mattress on the floor. These were based on iPhone photos taken from eye-level or lying down — scanning the room from the position of someone between homes, between selves. These are not grand subjects — and yet they carry weight.

Clegg says she’s drawn to spaces that are psychologically charged rather than neutral: “In public, you’re anonymous but observed; in private, unwatched but subject to your own character.” Each scene, no matter how banal, stages a kind of internal confrontation. Moving house is often a confrontation with memory. Mundane objects become symbols. A crumpled receipt, a chipped mug, a guitar cable: each item holds a version of a life once lived. Throwing something away often means forgetting it. Clegg’s paintings understand this implicitly. They preserve the transient — as if to say, this existed. I was here. This happened.

And yet, despite their photorealistic precision, clarity proves elusive. Stand too close and the painting begins to break the image down. A haze creeps in. Like waking up mid- dream. Or squinting through tears. These are images operating at the edge of recall — nearly remembered, not quite graspable. They remain suspended in the almost-real. “They always start from a memory,” Clegg says, “but I never paint from memory.” Instead, she finds or recreates images, translating emotional recall into something visual.

There’s an emotional logic to the way they dissolve. The fuzziness doesn’t weaken them — it’s the point. These aren’t paintings of moments, they’re paintings of how moments feel later. The way a scene erodes when you tell it too many times. Clegg is painting erosion, really. Not decay, but friction. The friction of remembering. She’s spoken about “misremembering as a methodology” — not a flaw, but a strategy.

There’s this line from Edgar Allan Poe (made famous in Peter Weir’s 1975 Picnic at Hanging Rock): “All that we see or seem / Is but a dream within a dream.”[2] And it could be easily be an epigraph for Clegg’s entire practice.

The title “Stainless” floats with contradiction: something pristine, something untouched — and yet the work is tangled with error, erosion, misremembering. There’s something almost devotional in that contradiction, a reach toward purity even as the surface blurs. Raised Catholic, Clegg recalls school confessions as ritual of compulsory guilt: “If you hadn’t done anything wrong, you’d have to make something up before you could leave” Confession lingers in her practice — not as repentance, but as performance.

A way of framing memory as rehearsed, unstable, emotionally true if not literally so.

This is where autofiction proves its power — reshaping the real into something emotionally precise, if not literally true. Think of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) — not for its content (grief), but for its obsessive looping around memory, trying to catch something that is already lost. Clegg’s work shares this quiet spiraling. It doesn’t raise its voice. It just lingers, gently pressing against the ribs.

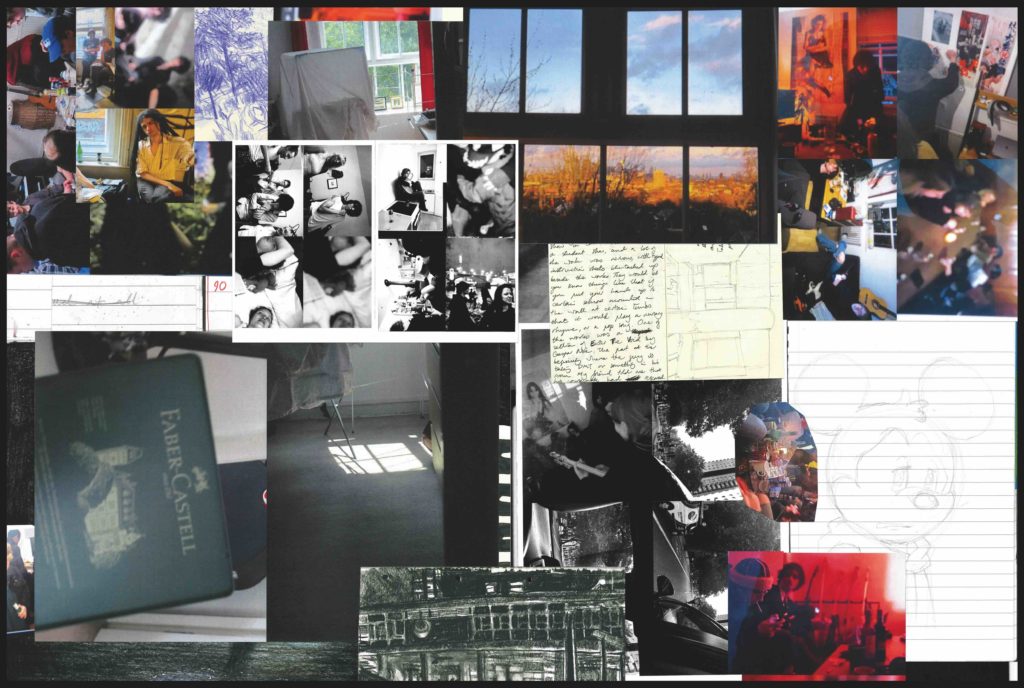

In “Blonde Redhead,” the rhythm of domestic transition is momentarily interrupted by a second group of paintings that diverge from the soft, transitional tone. Among them are five photorealistic renderings of studio arrangements: close-ups of staples, pens, blu tack, water glasses, tissues. Clegg calls these “trinkety DIY sculptures,” part homage, part subversion of the found-object aesthetic. These are objects that resist grandeur but assert presence. A cluttered tabletop becomes a self-portrait. They are arrangements of pause — fragments of the making process turned into something final.

But it’s not just objects. Suddenly, amid the stillness, a jolt: several paintings based on frame grabs from Gaspar Noé’s Enter the Void (2009). These frames — particularly the film’s disorienting opening credits — rupture the sequence. Clegg translates the frenetic energy of neon typography and techno aesthetics into slow, meticulous oil. The effect is destabilizing. Removed from their sonic context, the images feel theatrical and out of place. Their coolness, drained of motion and sound, reads awkwardly. Deliberately so.

Here, Clegg confronts recognizability head-on. The quote becomes a provocation: What does it mean to reproduce something “iconic”? Why replicate speed in a slow medium? The juxtaposition feels almost comic. She’s not chasing reference points to impress. She’s asking what gets recognized, and why. The painting doesn’t just interrupt the scene; it announces its intrusion.

The result is a productive dissonance. In the same breath as a paperclip and a mattress, we get a visual earworm from a cult film. It collapses high and low, domestic and cinematic, sincere and staged. The “trinkety” still-lifes and the lifted movie frames don’t compete; they converse in tension. Presence is asserted, then destabilized.

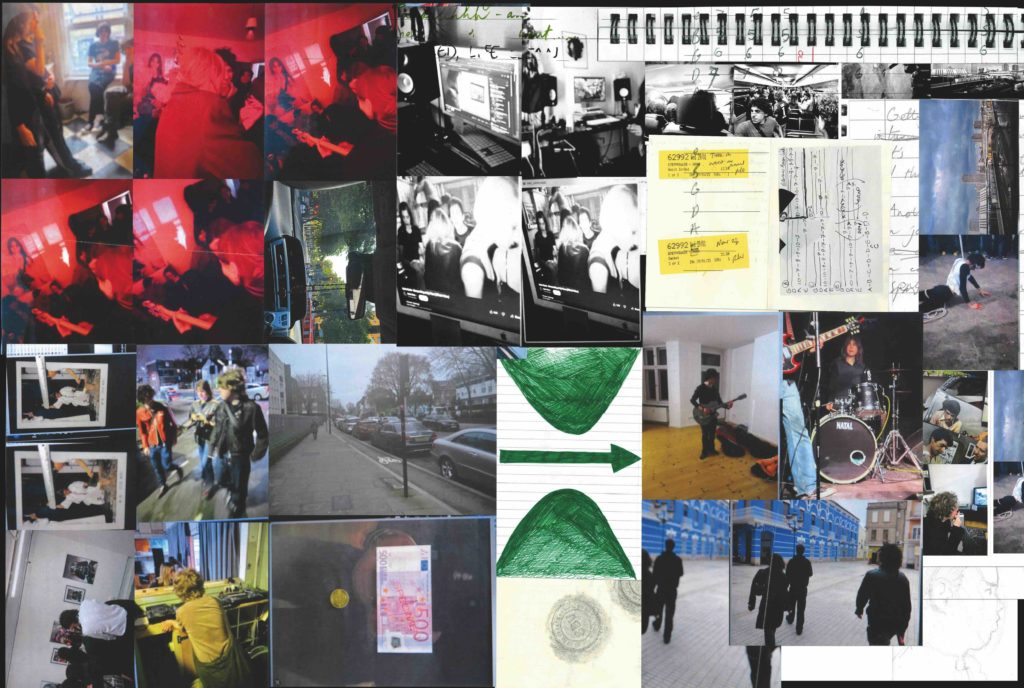

Lately, Clegg has been working on a series of small drawings and preparatory sketches in anticipation of her upcoming 2026 solo show at Schiefe Zähne in Berlin. These drawings aren’t studies in the traditional sense — they’re more like feeling-maps: delicate, tentative, searching. Often drawn from memory and then altered, they seem to test out emotional atmosphere before committing to paint. The pages are filled with objects half-seen, rooms half-furnished, people half-remembered. Some of these works have also been shaped by her recent reading of Tony Duvert’s Strange Landscapes (1973) — a book she described in conversation as triggering a kind of sensory recall: hazy yet vivid, like “waking up in someone else’s dream.” Like the paintings, these sketches don’t seek accuracy but emotional texture — a fidelity to how something felt rather that how it looked. There’s a kind of melancholy in these works — not loud, but insistent. A stillness that suggests inertia. The kind Woolf called “non-being” — the invisible hours of ordinary life. Clegg seems to work from inside that zone. Her paintings don’t rush to be understood. They hesitate. They drift.

And yet they endure. The invite slow looking, thoughtful projection. Each painting become not a statement but a prompt. A place to text memory against image. To ask: What do I recognize here? What do I want to?

Ultimately, Clegg’s work is not solely about the artist. It’s about what happens in the space between the artwork and the viewer — the mercy field of memory, association, and projection. The flickers of recognition that feel true, even when they aren’t. These are not simply paintings of things. They are paintings of what it feels like to remember.

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

¶

Like: I was here. Weren’t you?

[2] Edgar Allan Poe, “A Dream Within a Dream,” in The Complete Poems of Edgar Allan Poe (University of Illinois Press, 2000), 385–86