Michael Abel: Currently, the prevailing mindset within the field of architecture centers on crises. But there is a noticeable disconnect between these discussions of crisis and architectural form itself. This led us to polycrisis, the interconnectedness of multiple crises — economic, political, geopolitical, ecological, and technical — that feed into and amplify one another, exacerbating it all further. Our focus is trying to understand its formal implications, something you have explored extensively, particularly in relation to maintenance, housing, and your article “Indifference, Again,” published in Log at the start of the first Trump presidency, which presents indifference as a reaction to crisis.

Nile Greenberg: There’s a huge void now between the formal project and the political project, and this void seems to be growing more and more. To us, this is notable. However, this gap is not necessarily negative or a critique. Instead, we’re looking for a reaction – a position on how to bring meaning to form again.

Hilary Sample: Your idea to define and name our current moment as a polycrisis is right, and emphasizes the urgency of discourse to address and understand how to work today. There are many concurrent, complex crises, and the gap between architectural form and the political forces — creating its own crisis — is important to look at more closely through projects, writings, and constructing shared discourses. In architecture, there are many discourses, which is a crisis on its own because not all are shared. Architecture is a complex and difficult field, yet it’s also wonderful in that regard because there is so much to think about and act on or not act on and say why. In the context of something like collective housing, which is the most extreme crisis and a concern shared by many in my generation of architects, the gaps are large, imbalanced, and asymmetrical, which, as you say, exacerbate a polycrisis. It’s almost the opposite today of what it had been. Form in architecture was celebrated for being autonomous, yet was exclusive and selective. The discipline has turned towards more inclusive approaches in subject and ways of working. We have always tried to be radically inclusive. Our work focuses on art, studios, cultural projects, housing, and design research such as maintenance, which led to an article called Maintenance Architecture published in 2004, and later became a book. In housing design, the political project is so dominant that it creates a crisis of form in architecture. Form is rarely independent in housing; there are too many restrictions, not even constraints, which as a term seems to offer design potential. It’s also rare that the two things — form and political — don’t affect one another. In the case of housing, political form has gone so far over as to limit and restrict housing forms. On the one hand, there’s the latent idea that to design housing is to design towards a universal form as a solution, which seems accessible. Shouldn’t everyone have the same? Yet this approach didn’t work. More recently, an alternative direction is the idea of “half-building,” leaving the labor for residents to finish, which is different from simply saying residents live in a finished building that they change over time. That’s productive in one way, but if there is no kind of governance or oversight for this work, it can be incredibly problematic, and can produce a crisis of another kind. That way of working is happening in places around the world where housing is most urgent, but it also highlights the gap between the role of the architect and the government. For worker housing, which is the context I’m thinking of, it is still thought of as strictly designing housing units and often built without support spaces for culture, public health clinics, schools, and so on. Approaching this kind of design requires a practice, architects, designers, to think of everything all at once and to work more intimately with everyone. It puts us closer to politics and aesthetics. The political is always ongoing in architecture, as is aesthetics.

Michael Meredith: Aesthetics has always been political, but it’s not a stable politics or meaning. The same form can take on different politics in different situations and contexts. And even if form and formal techniques seem pretty stable and global nowadays, context is more and more unstable, local, and in crisis. Architecture itself as a disciplinary context is in crisis, the socio-political-economic context of cities, the climate environment, and so on. “Indifference, Again” started with Cynthia Davidson asking me to write something in response to Trump’s election in 2016. At the time, I connected Trump to Joseph McCarthy, through Roy Cohn, and then connected that to Moira Roth’s The Aesthetics of Indifference (1999), which referenced McCarthy throughout, along with Duchamp, Cage, Johns, and Rauschenberg. I compared these artists to a group of young contemporary US offices. I meant it as a positive act of support, thinking about that moment connected to ours. At the end of the text, I had a different conclusion than Roth, who lamented an aesthetic of indifference as an avoidance of politics, but put forth “Indifference, Again” as an active political and social act. I think the piece got misread a lot. People thought I was promoting being indifferent to all the horrors around us, which is not what I meant. I meant it as an indifference to authorship and to institutional academic aesthetics. This was before Trump really started to do damage and the politics has become more extreme. This feels like a long time ago to me now.

MA Aside from the perceived nature of the piece, you present indifference as a formal implication by categorizing architecture into two competing models: an architecture that expresses innovation, difficulties, and problems, and an architecture that performs and is defined by an increasing number of refusals, denials, and post-designations through an acceptance of non-design. At the end, you included MOS in the latter model – except for the fact that you are too obsessed with technology and too concerned with solving problems. Doesn’t that create a third model?

MM Right now, I think architecture is trying to respond to the end of neoliberalism – a post-OMA big-ness, after “surfing the waves of capitalism.” In recent years, many offices seemed focused on a sort of corporate management and bureaucracy, where it seemed they could do any type of project anywhere in the world, have corporate names, an array of letters in bold Helvetica type. Over the past few years, architecture has been about good management practices – it’s not a bad thing. But the ideal everyone was striving for seemed to be a large global office. Now, I feel like that has ended. There are more people interested in the smaller office and one that is more intertwined with life. We all want to live more intimately creative lives, not be a cog in some large-scale bureaucratic machine. Scale is political, social. I think this is probably the most important thing at the moment. Once you have an office of over twenty people, you’re basically corporate; I don’t think you can have the same relationship to the work. The huge offices of the early 2000s, like Herzog & de Meuron, even if they do incredibly beautiful work, are corporate and part of an industrial complex of architecture, tied to finance, and so on. Their work feels less compelling, maybe akin to an AI robot that can paint perfect paintings. This is a moment where many of us are re-evaluating the problems of scale, which seems to have run amok over the past few decades. What is the right scale for living, for architecture, for urbanism, for money, for labor, for identity, for politics, for dealing with climate change? At the moment, the crisis is, for me, the end of a kind of large model of architecture, the neoliberal model. I’m reading a lot of William Morris’s writings — News from Nowhere (1890) is amazing — and the Pre-Raphaelites and Arts and Crafts era feels somehow related to our current moment. In that time there was a Civil War in the US, the Industrial Revolution, British Colonialism, Socialism, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and William Morris. It had incredible inequity, change, and crisis.

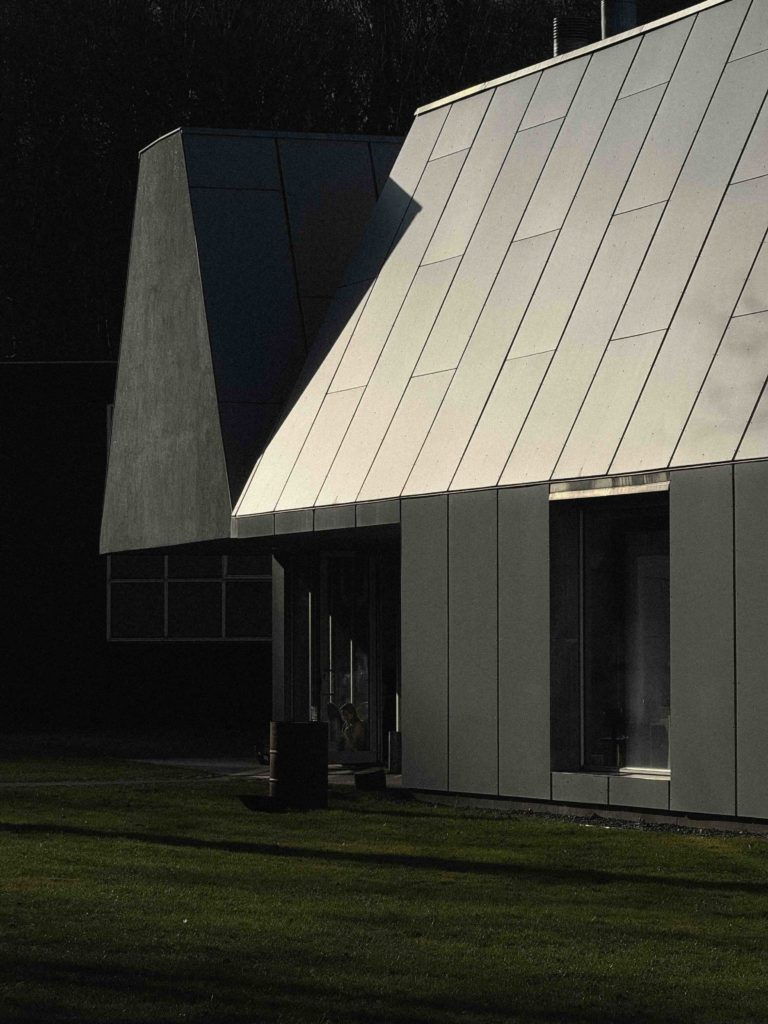

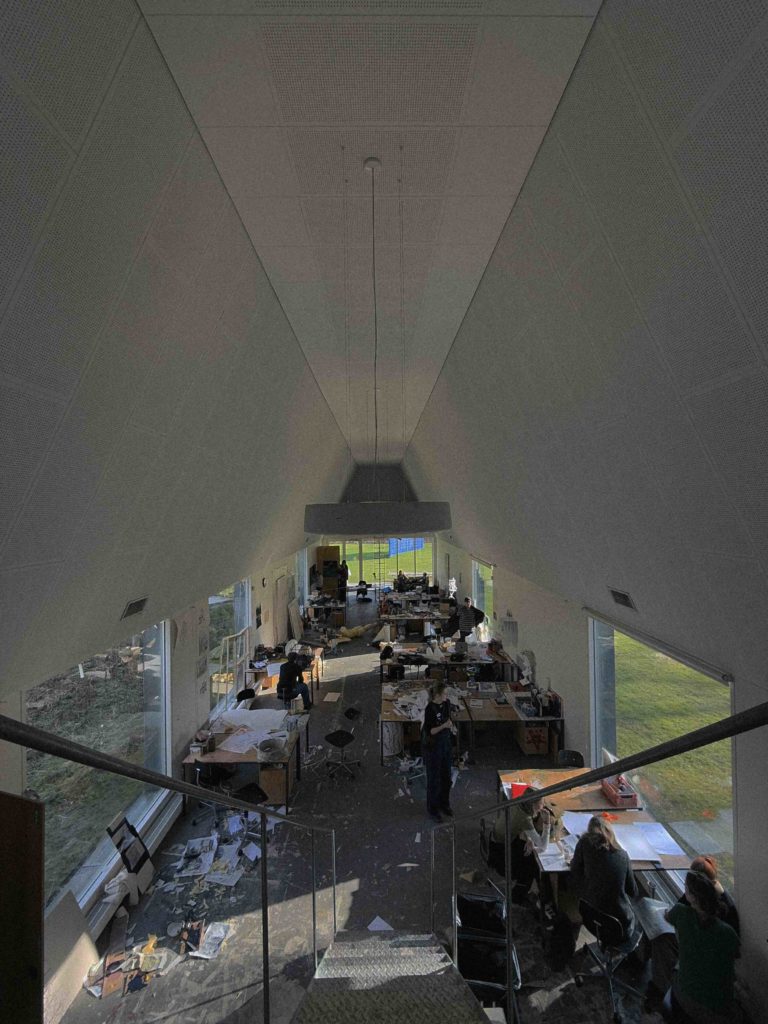

HS Our generation was taught to be generalists and not specialists. Today, that’s definitely a challenge. You have to make a whole set of choices now, that when we started, we didn’t have to do. No cell phone, no laptop, no computer, no proprietary software. To design, you could simply draw. And drawing was a way to work through a set of crises. Now it’s even almost a crisis just to start your work, because of the many choices, and there are certain challenges and expectations, and you simply have to know how to do things well, right? There is little space to make mistakes in the designing phase; 3D printing and AI produce perfect things. There is a crisis in the atmosphere of working, which is something that should be acknowledged. I’m concerned about how society values corporate, large scale over smaller architecture, that unless it is tall and shiny, it’s not valuable. This was my point in writing about maintenance, and something that artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles wrote about too. She’s been a great mentor to me. The corporate structures, even though their commissions are large, work at a smaller scale with odd restrictions, separating interiors or technical departments from design. For me, it’s a reductive process in terms of scope of work and skills, and so that environment of delegation, of trying to work on multiple challenges in the world at a large scale, winds up being looked at through a smaller, limited way of working. This model is a problem because it reduces discourse, ideas, and growth. Not all corporate offices work this way, so I want to be mindful, but building large-scale works for the sake of being big is a crisis that is only going to increase in maintenance, and I don’t see yet the urgency of this polycrisis taking effect in practice on this subject. There has been a movement towards a greater discourse about care since I’ve been writing about maintenance, and I feel that introducing this topic to architectural discourse has become more urgent yet needs great attention. What maintenance architecture shows is a catalogue of smaller works as being urgent. As a small practice like ours, we figure everything out at different scales and in different mediums: drawings, digital drawings, or models. And there is a permission to be more open and inclusive, to alternate unconventional ideas within the work. Everything is intimate, from the studio space to things like, we’re interviewing residents, sitting in their living rooms. It’s not possible to avoid challenges. Not partitioning the work is important, and it’s a way to work in a time of crisis.

NG Before computers, you said you were able to draw through the crises! I’m very interested in this as a technique or a way of thinking. I see the sequence of crises as an increase in disciplinarity alongside a loss of meaning in architecture altogether. But for me, this is the final moment before a kind of collapse, and the creation of actual meaning. Since at least 1850, there’s been a desperate search for meaning, from the Viennese Secession to Gottfried Semper’s In What Style Should We Build? (1828) – a series of great attempts by architects around the world to figure out what’s meaningful amid an ongoing erosion of meaning. Ironically, the only people that become great architects are those who operate as super authors – visionary individuals like Bruno Taut, Otto Wagner, or Antoni Gaudí. In the absence of shared meaning, it is not architects but singular artistic talents who rise.

MA The advent of digital tools have simultaneously produced neoliberal corporate offices making meaningless architecture and an inability to even start making architecture in the first place. Right now, we’re interested in certain ambitions of the early digital project, and in a nostalgic way, potentially. Obviously, it has failed. But I believe one reason it failed was a lack of any political stance. This moment really just became a sandbox for people to play in.

MM I’m not sure if it failed or succeeded. Everyone thinks we’re living in a Renaissance, but it’s probably the Dark Ages. The field is definitely fractured right now, and it isn’t because of the failure of the digital project. Actually, I don’t think it failed, although it was hard to pull off because its formal complexity was too expensive for most. I have no idea who paid for all of that, but class was inscribed in the complexity project for sure, and we’re definitely more interested in an architecture that is accessible to many. We started out indebted to parametric design, scripting, CNC fabrication, and so on. Some aspects of that are still in our work. Maybe the architectural discipline gets too academic and insular when focused on technique. Also, when you’re focused on quantity, getting attention, selling, and marketing — all the aspects of capitalism today — 90% of architects and people teaching eventually lose touch with architectural history, and the focus becomes about expert clever technique, rational argument, a sales pitch, a seductive image, a simple diagram, and logic. In schools, for years critics would say, “What is your logic for this?” Schools produce an environment of policing logic and architectural agency. It’s fine to be logical or technique-obsessed as an architect — I’m a technician in a lot of ways — but we do not make our work to be market-ready or to get clients, which I know probably sounds pretentious, or idiotic, or both.

NG But the digital project has imbued itself into every single practice. You can’t even make a dome without a computer anymore.

MM I’m referring to the digital as an aesthetic project – the curve, the swoop, the spectacle that comes with the complexity project. It’s more expensive and more difficult to build. We’re interested in working within an economy of lower-resolution geometries, and I think you are a part of this as well. There’s a sense of the non-complexity project as a return to something, conservative, or looking backward. I don’t think that “neo-postmodern” is an accurate characterization. It isn’t linguistic or semiotic. It isn’t symbolic. It’s just using these more buildable accessible forms and looking for different effects through them, a more accessible beauty.

NG As an architect, how do you engage with crises today – climate change, neoliberalism, war, pandemic? How do these issues shape your approach to architecture, both in practice and in representation?

MM You want to know how much agency architecture has in the world. I’m okay with solving problems. I know that was the thing with “Indifference, Again.” We do play with indifference aesthetically, but we still are interested in making the world better. We are focused on social housing as part of our work, and most of the research and publications Hilary and I have worked on are clearly engaged with social political issues, like her work on maintenance, and our work on Vacant Spaces NY, A Situation Constructed, An Unfinished Encyclopedia of Scale Figures, and a new project on public spaces.

MA One formal implication crisis has had on architecture is a kind of recent development into a language of repair. Which of course relates to maintenance.

HS I worked at SOM and OMA and thought about labor in architecture firms at the time — its relationship to making things as designers. There is no maintenance department within an architecture firm, for instance. That would be radical. As architects, we design projects for other people, and we also make work for other people. Our design work becomes real and needs to be maintained or repaired, and who does this work? We don’t ever know. It’s odd. On one hand, architects design, but the reality is that once a building is built then people need to take care of it and maintain it to different degrees and scales. Artists have been far more engaged and critical of the built environment in this respect, and interestingly enough, often put themselves into the space of the maintainer and ask the public to look at them. They took on a kind of responsibility, and also at the same time an artistic practice for them to talk about maintenance. And I thought, “Why is it so hard for architects to talk, work, and design about this subject?” It’s a question of labor, who is doing this work, and for whom. It’s one of the most important social and cultural topics. Our form of working still needs to be challenged and encouraged in relation to maintenance. I think also, to our practice and the way we set it up, we have been able to do different kinds of research projects, and work at smaller scales so that we can also participate in the physical making of a project. And we also make maintenance manuals, which are nicely designed! Our studio and design work, everything is made of parts. The studio space, the projects, the ideas, the objects, and so on. There is a gendered aspect to it. Unfortunately today we still see so much bias, and as part of being a feminist and woman architect there are ridiculous things I’m still fighting against. There are times when it is easier to make something with a longer part, but if I can’t lift it then that is a problem. It’s unconventional, but it’s a way of thinking about exactly what you’re describing, all these different crises, because they’re all always there. Right now, we’re living a moment where progress in equity is rapidly eroding, which we can resist through our work. We do a lot with little.

MA For some reason I didn’t pick up on this when I was at the office, but I never really read MOS as a sort of economic model or rebellion against certain neoliberal strategies. You want to solve the problem. Even the fact that you’re interested in engaging in social housing alone is something that most American architects today aren’t doing.

MM There is little to no money in this type of work, especially in affordable housing, as we take on other projects. When it comes to social housing, I believe some of our work fails architecturally. We have a lot of ambitions, I think we have good ideas, but I would say some can either suffer from budget cuts or a misalignment of values with clients. Is it our fault as architects? Maybe. We don’t have the power to do what we want, we have to collaborate with many others and can only argue for what we see as the better option. Sometimes clients just think we’re making it more expensive and they don’t understand why. This is all part of a larger cultural problem towards valuing design and how we should live, and if we can imagine different ways of living. Design quality doesn’t really exist in a pro forma, and everyone is worried about resale. If the architecture is too unique, too specific, it probably will lose market value. Doing anything truly differently requires the right client and situation.

NG It also seems like the top-tier institutions are not taking risks like they used to. You know, the decorators-of-capital architects are not contributing to culture like we are. We are searching for meaning, and that’s really hard. We are trying to find the moment between crises, of which there are so many right now — every young person knows this. Form is seemingly impossible to imbue with meaning, partially because it just feels like it’s unanswerable to these problems before us.

MM This is a working therapy session.

HS I’m going to stay on the topic of housing, in part because over the last dozen plus years, I’ve been leading the housing studio at Columbia GSAPP and researching housing and culture through the Rome Prize, which changed our lives. I’ve had great opportunities to visit many residential buildings around the world, particularly large-scale residences that have had varying degrees of crisis. They all share a tension. Because of their large scale they’re not often finished and remain incomplete blocks, yet they are inhabited. Often, that kind of incompleteness can be as good or better than what had been originally planned. In those spaces, what I’ve seen is another kind of care and labor, something I’ve been calling “tending architecture.” It’s a space that residents are taking care of themselves, but it’s a shared space, a communal space. It’s something that wouldn’t exist if architects hadn’t designed it in the first place, and if society hadn’t accepted it in the first place. But the buildings themselves were never fully completed as planned, and so they rely on residents to take it over. But still, it becomes somehow formalized, in some ways through informal and unremarked daily practices mostly related to maintenance. Multiple people are working on it together. In that respect, it’s a very different way of taking care of buildings or repairing than of maintenance, which is much more about a very formalized contract. You know exactly who’s coming. You know what they’re going to do. There’s a time limit. Tending is something else: it’s humanity at its best, which we need more of.

NG Maintenance architecture and tending are forms of politics that only architects can fully perceive. It’s important to everyone, they understand the implications of it, which is the promising part. It’s a good example of where architects have agency. But that lacks a language, which is maybe why it exists. We are continuously looking for a real politics that architects are implicated in. All these projects turn out so different, depending on who is doing it – Lacaton & Vassal, Sejima Kazuyo, or others. But that’s an intersection that can give form a lot of meaning again, if we could start to articulate a language for it.

MM I don’t know what the meaning is in the end. Meaning is the act of being involved, and working through it. For me personally, the meaning is the process, not the thing itself, although that said, I can get a lot of meaning from others’ work without knowing or caring about their process. And it is a question of how do you make work meaningful for someone else. That’s the magic trick. For starters, I think it’s got to be meaningful to you. There was one point where it seemed that the more intelligent you were, the more radical and weird your architecture would be. This isn’t true anymore. William Morris is deeply connected to this kind of political project — what might be considered a post-neoliberalism. I suppose this is what I’ve been working through lately. Morris was a socialist, an anarchist — and at some core level, I probably am too, both anarchist and relativist. He opposed the Germanic model of state-run bureaucratic socialism, instead advocating for a decentralized, anarchist socialism. He lived collectively with other artists, poets, and designers; he started a furniture company, a wallpaper company, a publishing company — he was constantly making, engaging with the world. He worked on a smaller scale, resisting the industrialized push toward modernization and standardization — the absurdly totalizing hegemony of reason. But for Morris, it wasn’t just about labor; it was about a way of being in the world. His writings look to the future, asking how we might find the right scale for life and redefine our relationship with the world around us.

NG Your work could be a strong representation of neoliberalism’s lack of agency. That’s an important thing to show.

HS We have been interested in ways that people live in the city, and different relationships to each other, to work. We are trying to understand housing as non-universal, rather than a minimal spatial requirement. And we have worked in contexts in different locations, understanding the specificity of living produces different requirements. In “Foreclosed: Rehousing the American Dream,” the show at MoMA in 2012, we imagined housing in a street with existing zoning. This is before co-housing became popular, at the peak of the pandemic. It’s a lot of reading, looking at work built historically and today. We want to make housing, and it’s challenging to enforce a project. For a young office, making housing in New York is virtually impossible. The city, the real estate industry won’t have it. We are looking for other ways in. If you study some of these policies, you find there are a lot of other rights that come along with housing: a right to shelter, a right to culture, a right to identity. That’s something worth pursuing more. This thread of thinking and questioning has become part of our books, Vacant Spaces NY (2021), and a new book on public spaces in New York, or the series on housing and also education with Petit École, which are very inclusive and collaborative projects, which lets us work on contemporary forms of design.

MM And also giving form to. We don’t really do development projects. We work with people we want to work with, a lot of times it’s with individuals we like, and with projects we believe could be good. I don’t need to do luxury.

MA What about absurdity and misreading? These are interesting responses to the moment. We have Dada art after World War I and then Roth’s Indifference after World War II. Both polemical rebellions of absurdity. Both included Duchamp. But Dadaism was more explicitly political, and perhaps that is why we are drawn to that. Then again, maybe there is little difference, especially when thinking about Rauschenberg. Do you think there is a problem with being explicit? I worry that the American left lost because of some sort of ambiguity.

In the documentary by Michael Blackwood, Frank Gehry, in a very laissez-faire way, would say, “The world’s crazy and falling apart. So it felt wrong for me to build normal architecture because it wouldn’t be the truth.” So his buildings, quite explicitly, look like they’re falling apart or under construction.

MM Misreading and the Dada-esque absurd are everywhere, and I’m not sure what to make of it, but that said, I still feel drawn to architects like Kahn, Hejduk, Eames, Gehry, Holl, Eisenman, Venturi-Scott Brown, and many others within an American context, and I like putting ourselves in conversation with other architects. It would be great if we had a local scene where we’re not constantly comparing ourselves to Europe, which is a very different situation.

MA On that note, can you expand on your housing project in New York City? I worked on several housing projects with MOS, and I think it’s a direct response to an economic crisis, making it a political, American act in itself.

HS We’ve been designing housing for fifteen years. I was discouraged from doing housing because it wasn’t thought of as an intellectual project. I think of the legacy of the 1932 MoMA show “Modern Architecture: International Exhibition.” Housing was originally meant to be part of that exhibition, but it eventually became a separate, specialized practice in the US. MoMA has continued to support housing exhibitions, and it should do so even more. Today, some firms only do housing partially because of the complexities around the laws of building, particularly affordable housing and housing that is subsidized. Housing is not universal; the specificity of living around the world produces different kinds of requirements and spaces. In Washington, DC, we worked in two historically important neighborhoods elected by the mayor’s office to receive more density. The challenge was that it literally was on the border with Maryland, so as far from the city center. Should we have refused to do this project? We tried to push for as much as we could, and were successful at having a mix of apartments, studios to four bedrooms, single loaded corridors with light, it has a penthouse. It might be the only affordable housing project with a penthouse.

MA I find that a very compelling argument, an argument for space which is non-universal, along with the contradictory specificity of housing. That’s the direct opposite of what happened with certain ambitions of modernism.

HS In general, with housing, I think there tends to be this latent idea of universality, because it’s a large challenge, and the perception of the economy tends toward a mass-produced solution. But then, form becomes singular. For a long time, NYC HPD had larger-scale units, which was a challenge for developers to build, because the market size is actually smaller, so there was a mismatch of the structural frame, and the aesthetics of the form were challenged. Some buildings are stepping in plan because the affordable units are bigger in scale, mostly because affordable means families or larger households. It’s important to talk about residential buildings as residential but not as projects, as they are built and people live there. They are also not products. Large-scale housing from the late 1960s in Mexico, in France, in Italy, where the residents got together and managed the buildings. Corviale is like that to some degree; residents took it over and built their own apartments. The main structure was built and then the residents finished the inside. We are working on a project in Paraguay that will sadly suffer a similar fate. I am against half building something; the government broke their promises, but they defend by saying something is built. It doesn’t help people to put the burden of completion back on vulnerable populations. It’s not a popular thing to say, but important to speak up. This project cost $4 million. People spend more on art.

MA People have plenty to say about modernist social housing, to the point where they say it has ended modernism, whether anyone agrees with that or not. This might be a reaction to a lot of small-scale solutions, but I do think that keeping projects like that in mind are important and powerful when thinking about political solutions. Do you still believe in the scale of housing like Corviale?

HS That’s a good question. It’s something I have thought a lot about because the urgency and need for housing is a crisis and it’s not getting better. Corviale is a kilometer long and originally they didn’t build any support services; for instance, the residents advocated for buses since it’s an hour or more bus ride to the city center. Now you can’t just build massive housing without cultural programming or without a diverse and smaller-scale urbanism. For me, I’m more interested in a model like Isozaki’s four residential buildings in Japan, which was a competition awarded to four women-led firms. It is my understanding that his office oversaw the construction, which enabled their studios to have an opportunity to design this work. This model is unconventional and something that could be done again to address scale in housing, and give younger offices opportunities. This competition also included landscape studios. Another version of it could include communal and cultural functions. Housing is not a problem one firm or person can solve.

NG So do you think Crisis Formalism is possible? Does it even make sense?

MM Well, it’s hard to say because there are so many crises. Some have a very clear idea of what the crisis is, and it may not be yours. When we started our office about twenty years ago, there were so many crises. Early on we did all these videos, filming models or projects and making up stories about them. One was called The Zombies Are Late. It was about a group of zombie architects that time travelled into the future to escape the quote un-quote Krisis™, but something goes wrong and they arrive off-course late at night. So the zombie architects (shown as architectural scale figures) are there, at night, arguing with each other about what they will see when the sun comes up.

HS I’m not sure what Crisis Formalism means exactly, and how it is meant to be used in architecture. In Elaine Scarry’s book Thinking in an Emergency (2011), she writes about how in moments of public health crises, people suspend protocols, and they suspend beliefs because they have to solve this urgent problem. After the crisis ends, they revert back to the policies, as opposed to saying, “Wait, that really worked. Let’s keep it.”

MM Are all the crises equal?