Scott Cohen: We are talking about the architecture of exceptionalism in the context of what you have called the “entropic city,” as opposed to prior coherent types of morphology, such as Manhattan’s. We are arguing about two conditions: a response to the entropic that is intentionally represented by OMA’s unusual and evidently arbitrary shapes, as opposed to other examples that produce similar effects, not rhetorically motivated but rather caused by all sorts of demands and technological advancements, as is the case with pencil towers or the New York Athletic Club (NYAC), where programmatic variety had to be absorbed into an otherwise determined body.

Robert Levit: Few works are exceptional in the specific way OMA’s are. Obviously not typological in origin, they are inorganic in form and stranger than almost any others. It was not Koolhaas but Somol who, with his “theory of Shape,” touches on important questions related to the city today. OMA’s CCTV, Casa da Música, the Whitney addition project, and Seattle Public Library are inscrutable, monumental objects, crystalline, without traditional hierarchies of part to whole. They are single objects, but neither are they simple elemental objects — another, different trend in architecture. They neither allude to creaturely coherence often found in curvilinear forms, nor simple forms, nor do their shapes derive from structural logics, even if their actual structural solutions are matter of fact. It is their singular, inscrutable difference, the absence of organic relationships of traditional coherence that relates them to the characteristics of the contemporary city — a city no longer defined by its morphological coherence, but rather by one thing after another, each a seemingly arbitrary contribution to an accumulation of arbitrary instances: a city that is a field of difference in which every building is indifferent to the next. It doesn’t matter if these objects are in cities that still retain their historical coherence, have lost it, or never had it; the projects all point in the same direction: a vision of the city where none will have it. In each context, the exception registers the dissolution of norms.

SC It is the imagined as opposed to the actual dissolution of norms that architectural discourse needs. Architecture can only go on for as long as the dialectic between norm and exception survives.

RL The entropic city is thrilling and horrifying in the way that radically new modes of urbanization, of modernization, always are. Marx’s endlessly quoted phrase “all that is solid melts into air” comes to mind. The taste for distinction, the weakening of social norms, the weakening of regulatory regimes, the scale of development are all contributing to a radical refashioning of the city.

SC This is 100 Federal Street in Boston, known as the “Pregnant Building,” by Campbell, Aldrich & Nulty (CAN), 1971. How does it compare to CCTV?

RL It is very different because Koolhaas’s forms are not so orderly.

SC And yet, the untheorized Pregnant Building, like CCTV, has no parts. It arbitrarily pressurizes the space of the city by encroaching on the spaces of other buildings. Its extreme autonomy is shape-like, even though its form is rational, not manneristically distorted like CCTV. In lieu of any means to create such a relationship between architecture and the city, Koolhaas is compelled to encapsulate this dialectic within the single building. His means are so idiosyncratic as to be possible only for special institutional programs. The picturesque effect writ large by the Pregnant Building is writ small and cumbersome in the tormented plans and interior elevations of CCTV’s offices. If this is the result of a strategy, it seems ill-fated, even “tragic.” You have to wonder, is it better for sculptural exceptionalism to be formed by buildings or between them?

RL This is one of those questions to which there need be no categorical answer. Both seem to me to be good in certain situations.

SC First of all, your whole argument for Somol’s shape and his theory are categorical. You categorically objected to the gradient patterns which OMA deployed in order to effectively hack out the corner in their Lexington Ave/23rd Street building. The way in which the 23rd Street project redefines the urban block reflects Alan Colquhoun’s narrative of the superblock, which, as he argued, coarsened the city, from fine-grained lot aggregation to colossal whole-block buildings — i.e., Koolhaas’s “bigness.” In addition, you categorically applied the criteria of whether or not the arbitrary exterior deformation pointlessly obtrudes on the interior.

RL The Lexington Avenue building belongs to neither category — arbitrary shape or “pressurized” space between buildings. Rather, it seeks to tie into and transform a context through the use of a gradient transformation. What I object to, or at least categorize as entirely different from what we are talking about, is how the Lexington building substitutes gradual transformation of existing fabric into something different for the bold, abrupt difference about which we are speaking. This Lexington building elevates the status of perishable context, recuperating continuity, reestablishing the coherence of the block as a totality rather than embracing the structuring conditions of difference.

SC It is difficult to imagine that the doubling of towers at CCTV, both too small to contain normal office floor dimensions, was good for the client. It is a sacrifice made only for the exterior figure.

RL Any institution, whether offices or a museum, is entitled to determine its programmatic parameters. Why should we assume that CCTV suffers from some defect of its spatial arrangements? Optimal floor plate size is derived from client wishes and institutional practices and goals, not from some objective standard made from the preponderance of cases.

SC I would have thought that you were interested in the CCTV as a different but still normative office building, not a distinctive expression for an institutional program.

RL Nope. The strategies are a-typological and not meant to be typical. Also, for all we know, people may like working in smaller floor plates.

SC Obviously, a client does not ask for office floors to be more than half full of elevator cores. Whether those little offices are nice to be in is not the point.

RL Why not the point? Not a model, just unusual and good. Anyway, in a city of difference, reproducibility and distinction contest each other.

SC The pencil luxury towers, with their inefficient plans, are motivated by other aims, not by the authored anti-figural aims of shape-making.

RL And?

SC And there is likely no scenario in which the super thin plan is sought after for an office building. Only rarely are special institutions designed to have small administrative office towers. CCTV only wanted or accepted the figure. Aren’t the sensibilities of such idiosyncratic clients and outcomes comparable to the evanescence of any ongoing, developing context?

RL Each is a stand-alone instance. Idiosyncrasy or uniqueness are not the same thing as evanescence. And, CCTV is no more an example for others than the Pregnant Building. All sorts of converging factors enter into such choices: symbolic goals, real estate dynamics, unusual programmatic aims. The point is that buildings arise through a confluence of circumstances including special efforts to thwart what is generic. The ethos of difference is antithetical to the ethical aesthetic paradigm of the typical, the typologically relevant. And also quite different from the play of forces shaping the pencil towers.

SC My argument is only about the degree to which it departs from the norm. This matters. I would assume that the evidence that CCTV is tethered to certain norms of the contemporary city, both pragmatically and symbolically, interests you a great deal.

RL What CCTV does is distill how the contemporary city has come to be a concatenation of buildings, all of which want to be exceptions. Each building is a monument. Elsewhere I have also argued with you that a related response to this new city of individualized and autonomous artifacts is one of ascetic classicism — such as works by Diener & Diener. Arbitrary idiosyncrasy or a new stand-offish classicism seem related responses to the same emergent conditions of an entropic city.

SC The desire to be exceptional figuratively seems commensurate with the old city, in which special buildings for special functions always departed from normative constraints that shaped the fabric. The examples that really should excite you the most, I would think, are those that differ not evidently owing to their exceptional program, but rather cases like the Pregnant Building and the pencil towers, which are different because they are outsized sculptural anomalies wrought by causes/circumstances/opportunities that produce extreme and irregular effects, which exemplify the essential characteristics of the entropic city. The symbolic exception of CCTV is too obviously not governed by the norms that this city is being built according to. Therefore, we know that it is not just another office building that happens to look strange.

RL What is caused is something else altogether, and not what I’m talking about, which is the broader shift towards a culture of difference and distinction combined with an allied indifference or aversion to convention. These impulses are independent of such “caused” circumstances. I am talking about how architects with rhetorical purpose respond to the city, subscribing to a pervasive goal of distinction as an end in itself. CCTV distills and accentuates the unleashed arbitrariness in this climate.

SC In the cases of the super-talls and Pregnant, the extreme effects seem all the more arbitrary and exceptional because of how purposeful we know they must be.

RL CCTV is something else that Somol identified in his shape-versus-form observations, an idea that bears some resemblance to practices identified by Michael Fried in “Art and Objecthood.” Matter-of-fact actions upon materials produced un-composed objects that are not the products of composition or artistry. The facticity of Serra’s sculptures resulted from simple actions upon steel. Of course, in architecture this is not possible to achieve. Buildings are mediated and purposeful assemblies not reducible to a simple action upon a material. But, the confluence of simple arbitrary forms and matter-of-fact construction lend to OMA’s works a quality of sheer material facticity.

SC Very simply put, it would seem that CCTV is not a sheer fact, but rather a contrivance compared to cases that hew closely to or are undoubtedly motivated by normal causes, like the Pregnant Building and pencil towers, which are piles of mansions in the round that we can imagine would excite Koolhaas because they became plausible not by design but by the convergence of profit and technology. Certainly, they are not the result of any composition aimed to produce a particular effect on the skyline.

RL Whether Koolhaas would be excited by the “motivated” aspect of pencil towers or not, that is not what CCTV is. Yes it is contrived. Composed? Not so much. Its mineral form feels mute, like a geological fact. This is the effect of its contrivance. This question of whether Koolhaas or we should attach some special value to the special motivated circumstances that produce the pencil towers reminds me of an often misunderstood idea of ornament articulated by Semper. Ornament, according to Semper, is not the product of how materials are worked, the marks of tooling, or of joinery — that is, the result of “motivating” forces, as it is often misunderstood to be — but the imitation of such effects once they are no longer present, like the stone metope of classical masonry architecture imitating wooden construction. Casa da Musica, for instance, is NOT the motivated vernacular. It is the imitation of such motivated circumstances. And if we recall all the contrived program-packing diagrams which provide the alibi for its asteroid form, we should acknowledge that these diagrams contrive motivations for the strange form rather than the form arising from the “real” motives shaping the vernacular. And architecture, whether Koolhaas’s, Venturi’s derivations from Main Street or the Strip, Le Corbusier’s from ferroconcrete, or Mies’s from steel frames, occurs at that moment when it is no longer motivated as you would say. However, let’s admit that many architects have been fascinated by what they perceive as necessary and natural. But then they imitate this condition where it does not prevail, and in that respect we might say that ornament is the key concept to understanding what architecture is.

SC Yes, but Koolhaas was excited only about extreme results of the so-called natural causes. He was interested in playing the cards we are dealt, rather than compositional or anti-compositional games. Those cards are economics, the market, limitations imposed by tastes of consumers, etc.

RL Interested in them, yes, but not what he has done as an architect.

SC If I were to take my argument to its logical conclusion, the exception would only come about or appear to come about for non-rhetorical reasons.

RL True. But, what you are describing is something else — and that something else does not recognize the drive towards difference that is independent of such circumstantial motivations, and also different from what I am describing in this handful of OMA projects. The contrivance of arbitrary shape in OMA’s work is unmoored from the very constraints that attracted him in Delirious New York. Or perhaps we are left only with the towers of Delirious New York’s endpapers; they have finally stepped off of and freed themselves from their hitherto regulating block-bases. This rhetoric of arbitrary excess unmoored from constraints, these arbitrary contrivances, make visible the drive toward distinction, the collapse of agreed-upon aesthetic norms, an unbridled marketplace individualism, weak regulation, and a constellation of contemporary forces and sensibilities. This is also what is relevant about CCTV: the pencil towers are a kind of natural phenomenon, CCTV is not.

SC One of the main reasons the Pregnant Building is so distinguishable is the plan of the city where it is located. Are you saying that the city is “natural,” this building is simply intended to be rational and is reducible to its modularity and, therefore, the relationship between it and the city plan seems unintended and can’t be understood to have any relationship to the non-classical effects of shape that it appears to have some affinities with?

RL I am not saying the Pregnant Building is inadvertent. But I don’t think it feels arbitrary, either. As to whether the city is “natural,” there is a quality to the city that does feel a bit like weather to me because the diffusion of decisions, the overlapping responsibilities, protocols, and on and on does make it feel sort of natural, that is, inhuman. Of course, it is not. The city-at-large feels very different from the purposefulness of individual buildings.

SC Yes, of course. Yet, despite the fact that it depends on space beyond its control, you and I know that the effect of the Pregnant Building is just as composed as the CCTV. The outcomes in both cases are not consistent with urban design or compositional conventions of architecture. Why then isn’t the measure of their shapeness the evidence of their arbitrariness, aloofness, etcetera? The sloped surfaces of the Pregnant Building very clearly establish its exceptional identity. The city, right then and there, is not at all natural, precisely owing to this particular one-off building-to-building relationship — an unusual relationship between buildings that are relatively normal unto themselves.

RL Yes, the Pregnant Building produces one kind of arbitrariness, cheek-by-jowl with other buildings, but there is a big difference between this building, which is not particularly mysterious — it expresses its underlying modularity of spaces regardless of the fact that it is unusual — and CCTV, Casa da Musica, and Seattle, buildings which feel weirdly and inscrutably formed.

SC When a shape is exceptional in this particular way, with these oblique corners, the 3D effect is very aggressive and quite like shape. It calls attention to the non-composed nature of space that elsewhere is the result of office building standards and the ground plan of the city.

RL Yes, true. It reminds me a little of the excitement we used to share about the Boston Athenaeum with its precise classical shapes, its stylar façade and cornice, and the apsidal room tucked into the angled space made by adjacent buildings. It is nested perfectly in the leftover spaces of haphazard circumstances around it.

SC The Pregnant Building is related to that, yes, but is very different given how extremely simplified and gigantic it is, and mainly because the amount of space between it and the surrounding big buildings is similar in size to the buildings themselves. At the Athenaeum, there is a very clear hierarchy between the big figural features and the little gaps (empty poche) that you’re referring to.

RL The Pregnant Building is a modern version of a building from Campo Marzio, well-formed and jammed into a jumble, while CCTV is itself the strange form.

SC This type of urban irregularity is now being imitated by some new districts of chunky entropy, such as Cambridge Crossing and Harvard’s Allston development and many others in other cities. You may not like master plans designed to produce variety and picturesqueness. But the Pregnant Building’s rational arbitrary shape appropriates the plan of the city to produce the inverse 3D shape effect that you admire in the CCTV. Here, it is the space, not the object, that produces it.

RL It is a different sort of arbitrary. The idea of teaming autonomies like Campo Marzio’s is a related but different kind of arbitrary. I think it is important to distinguish between these two different categories.

SC What a shapely autonomous building can do is dependent on the morphology — the urban plan and its density. OMA’s Shenzhen building, which is similar to the Pregnant Building, is of no consequence because it can’t have any impact on anything around it. Now I am beginning to wonder if there is an argument for picturesque urban planning, like the Brooklyn waterfront by SHOP and Allston by Gang. And when there isn’t an interesting urban plan to respond to, one can try to make a giant sculptural exception like the CCTV, if one wishes, though that will likely only be possible for special institutions since that very example is not viable for a normal office building — though its resultant dimensions would be more possible for housing.

RL Sure, the picturesque adjacencies of a New Campo Marzio. But, Boston is unique, not purposefully picturesque, which raises another issue when it comes to such effects now — how to plan such circumstances or, dare I say, contrive them. To contrive such urban plans is an even greater contrivance.

SC When the rhetorical goal is anti-rhetorical it begs the question as to whether it achieves the desired effects as compellingly as the genre of things it is pointed toward — i.e., the genuine article: the caused emergent mutations.

RL Back to ornament. Is the stone metope less “effective” than the wooden original that it imitates? The goal is not the natural circumstance but rhetoric. The rhetorical thing is not meant to be the real thing — even if architects love to claim necessity as their ally.

SC Whatever the case may be, the dialectic between the norm and exception — the idea of an architectural articulation that points to another possible city — seems moot within the reality of today’s entropic cities. What does it mean for architectural discourse if the city is composed of arbitrary and meaningless stylistic differences building object after building object? Any style or exception will do. I don’t feel that either the bold nor the very subtle cases of exceptionalism of old, within the more coherent older city, seem meaningless and unmotivated in this way.

RL I am arguing that these arbitrary shape buildings not only point to but constitute the material of a new sort of city, whether you like that city and its architecture or not. As for the meaning of buildings, as the world around them changes how they are understood will change. Need we worry about that? When Mies represented his glass towers next to low medieval buildings, were we supposed to worry that someday that contrast would disappear?

I am reminded of one of our discussions years ago when we were both on the same side. When Johnson built his Lipstick Building in Manhattan, Gandelsonas objected to it. His interest in seeing the city built out with typologically consistent works, like his two Buenos Aires towers, made it hard for him to accept the Lipstick tower deviation. But we both liked it regardless of what he thought it foreshadowed.

SC Within the entropic city, the Lipstick would neither excite me nor upset Gandelsonas. We were only able to be excited about it then because of the legibility of its departure from norms we recognized to define the city. CCTV doesn’t make us desire the entropic city, but rather to remember the old forms and cities that enable CCTV or Lipstick to point radically toward the ultimate entropy.

RL That is not true for me. I don’t need to think of New York to like entropic cities like Toronto, Houston, Miami, and I didn’t then or now regret the prospect that the exception might someday be the norm.

The irreversible transformation of what was into something else does not upset me.

SC We are mixing up two things: qualities that we like or don’t, architecturally and urban-morphologically, and architecture as we need to think about or imagine it — i.e., the dialectics, whatever they may be: norm/exception, culminating in this most strange sort of inscrutable object, a sort of exception measured at a coarse urban scale, not at the finer scales of architectural syntax.

RL I don’t think that the norm/exception becomes a failure when it is superseded by a new norm that reflects new forms of city-making. These new buildings, this new vernacular of side-by-side difference that today feels exceptional, will cease to be so, probably already has for many people. Why the regret?

SC The distinction craze, as you have very aptly named it, leaves architecture flailing. Why should a chosen style or exception, adopted convention, or its denunciation matter? Moreover, the big-scale disaggregated chunkiness that you are valorizing demotivates the typo-morphological interrelationships manifest by architecture.

RL I don’t feel much differently about contemporary examples of the architecture of the “good urbanism.” And there can be good versions of both chunks and works that attend to coherent morphologies. So, the question for me then isn’t really which urbanism produces better architecture but the character of the city being produced.

SC I can’t agree that the facades of traditional buildings are just as unmotivated as today’s are. Conventional hierarchies contradict urban- and interior-necessitated repetitiveness and are thus tension-filled. As for the norm-plus-exception dialectic at the big scale, the newest Foster when seen on the Madison Avenue side, lifted with sloped overhangs and slightly tapered above, and the Pregnant Building, are both more exciting than CCTV because of the legibility of the contexts that their autonomous geometries deviate from.

RL I don’t agree about what seems exciting. I don’t feel particularly attached to those tensions or that they are the sine qua non of what is exciting. I mean, the new forms of the city are interesting for a whole host of different reasons that I am trying to capture in my descriptions.

SC When I see the shape on top of that tower by DSR in Hudson Yards that you like, I can’t care about it. It just doesn’t matter. And I am not sure the CCTV matters that much either. The architecture doesn’t matter in any of these districts. And I don’t think exceptionalism really matters anymore either. This is what I’ve been arguing all along.

RL As you just noted, we don’t agree, either on the DSR building, CCTV, nor that the architecture doesn’t matter. I do agree that in the new urbanism of chunky development, the old tensions of the sort you mean, subtleties of window pattern for instance, don’t much matter usually, but I don’t agree with painting the OMA projects with the same brush as other projects you have brought into the discussion. None to my mind capture as effectively a vision of the entropic nor operate so clearly and effectively as the OMA exceptions. And none are as organizationally interesting as the Seattle and Porto projects, nor are they as interesting in terms of scale and local impact on the city.

SC The contradictions that are inherent to architecture’s scale develop in many ways that implicate the city. Such things as frontality versus all-roundedness, the turnings versus finitude of corners, spatial sequences both centripedal and centrifugal, extrusions of plan versus elevation profiles. For you, when conventions are dissolved, the OMA projects operate better and others don’t as clearly. But if the whole game is over, how can it be played better or worse?

RL The game is over? The organizational richness within Casa da Musica, for instance, stands on its own. I don’t share this sense of doom. Nor is Casa da Muscia some generic lump, so yes, better.

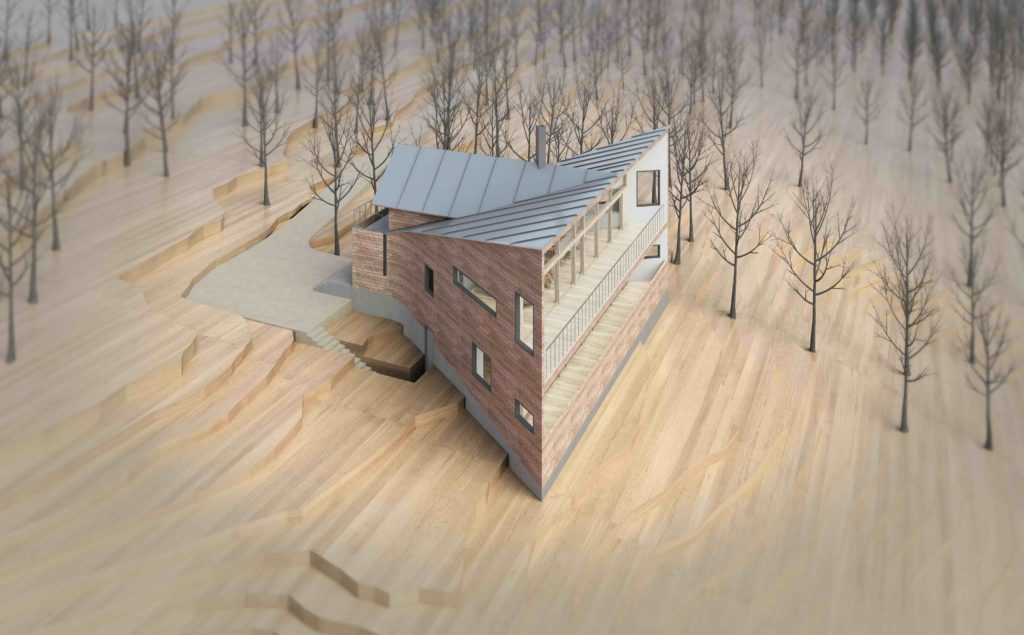

SC What do you make of this recent Koolhaas project in Zeller See, Austria, the Alpine House?

RL What of the Zeller house? What interests you about it or houses more generally? How do they relate to our discussion? This house, like other OMA houses, feels like houses made by a practice invested only in the big issues of the city, its big buildings. The houses do not reflect an investment in the atmospheres and vocation of private life. And while the Bourdeaux house is so smart about the accessibility issue, the idiosyncrasy of houses related to the peculiarity of private individual cases feels trivial — artsy villas in essence. There is nothing surprising about idiosyncratic villas and therefore, as you might say, no tension in being strange. By contrast, the impact of an exceptional public building including places of work such as CCTV is enormous.

SC As you have done with large buildings, we can choose to understand houses to be permutations of architecture’s predicaments. I would argue that this house is an arbitrary single figure and in that sense is analogous to other projects by Koolhaas. It is also indicative of his insistence that architectural novelty best emerges from problems and program rather than form.

RL Haven’t the most important houses been those that were paradigmatic rather than most exceptional? The ones that suggested reproducibility as houses or housing units? Of course, sometimes unimportant buildings can be sources of great pleasure with imaginative inventions of domestic life. For instance, Lautner’s or some of Wright’s most unusual houses, such as the Lykes House in Phoenix. Many of OMA’s houses invent such unique circumstances.

SC Yes, of course. But we are talking about the occasions when buildings are also analogical. The question I am tabling now is whether and how a house can be. Such a house must follow from a criterion we have previously agreed upon: as opposed to only representing the personal tastes or whims of the unique or rich client, the exceptional house must evidently elicit the desires of guests or potential buyers. You and I have agreed that the imaginability of impersonal desire is important for almost any client. It is also important to distinguish the arbitrarily figural houses that are in normal sites from those unconventional houses that are responding to idyllic, extraordinary natural settings. What I’d like to get to the bottom of is the architect’s compulsion to produce figure, whether shape or form, which is unrelated to the client’s desire for the impersonal. I am diagnosing the figural house to be indicative of an unconscious desire to represent the figural difference that, in today’s entropic city, each building aspires to.

RL You have tried to persuade me that my own recent house design exemplifies this ambition for shape distinction. You referred to the figural implication of the fillet between the entrance volume and the main body of the house, and how it is an odd detail, the purpose of which is to make the whole house a single figure. You have also pointed to the bedrooms, which you argue are compromised by their subordination to this figure. But I think the house would appear in many ways conventional, albeit with some unusual details. I don’t think the bedrooms are compromised, if clearly contained within an overarching figure. Because the figure of the house is formed by a desire that I assume would be shared by many people — to relate dramatically to the stunning river and mountain view — the form is driven by this relationship, not an ambition for difference. Your assertion depends upon two fillets, hardly comparable to the more extreme eccentricities of shape we have been discussing.

SC No matter what you say, you must have wanted the house to continuously transform — i.e., scale up continuously as opposed to discontinuously, as would be the norm — from the front door to the big glass screen of the open main living space. This is too evident in the shape of the whole house in plan and section to be denied. Everything in the project could be subordinate to this imperative.

The figure is a sign of something in its own right. I would also surmise that you are driven to reinscribe the dialectic between the total exterior figure and the multiplicitous spaces of the interior. In this sense, your house rehearses figure versus stuffing in MMM’s Low House, which in turn reflects the same dialectic in NYAC and OMA’s Zeebrugge Sea Terminal project.

RL The stuffing part was not particularly difficult to achieve in my case, thus the tension is less dramatic than in the projects you mention, even if it does work within a regular figure. Also, and by contrast, in the Porto and Seattle buildings, the program is arranged to contrive strange shapes, which is not the case in my house.

SC My earlier houses also worked on the dialectic between exterior figure and interior stuffing.

RL I think generally your house designs seek out and then manage disruptions to figures as a goal in itself. I think you have wanted questions of internal disposition and room arrangement to mess with totalizing figures.

SC My latest series of houses are driven not toward the Koolhaasian or Venturian dialectic of single figure versus interior stuffing but rather toward isomorphic correspondence, which I regard to be the ultimate horizon of possibility specific to houses and, in rare cases, to certain types of institutions. The conventional and thus seemingly non-arbitrary forms of these houses are necessarily perturbed by the effort to absorb circulatory, structural, solar, and other systems that are pressured to allow the outside to conform coarsely to a more remarkably coherent interior.

In Koolhaas’s Alpine House, the sawtooth roof is an innocuous type too, though non-domestic (it’s an urban top-lit loft or factory). He converts the adopted type into an arbitrary figure first by sculpting it crisply with no parts, details, or overhangs, and then by making the sawtooth’s clerestories progressively angled. The implication is obviously physiognomic or zoomorphic, like a caterpillar climbing the hill. I imagine you will find objectionable this figure that alters a serial system (i.e., the sawtooth turned into a progressively steepening mohawk).

RL Yes, it differs from the sorts of arbitrary figures we’ve discussed by deriving a form of organic coherence through its zoomorphic reference. In my own house, there is no super-added representational goal. It does not manage its figure from such an external reference; it is, more simply, what it is.

SC The Alpine House’s figured arbitrariness seems to me to be related to the entropic. Single figure houses that are explicitly not conventional do not originate in an organic or functional principle.

RL Being unusual and being arbitrary are not the same thing. The house may participate in the culture of difference, but its combination of utility in the use of the sawtooth skylights, which are then shaped zoomorphically, is not arbitrary. Or rather, the zoomorphic is arbitrary, but with an esthetic goal that differs from the other OMA projects we’ve discussed, while the sawtooth is not arbitrary no matter how abstractly detailed. You are arguing that any odd figure, arbitrary or not, is part of the general tendency toward individuating buildings in the city. I agree on this latter point, but think it is trivial in a private home, even if I agree it comes from a related impulse. The sawtooth coincides with your preference for demands external to the architect’s choice. You’re trying to find the sort of causes that produce the pencil tower. But that is not what the other projects we’ve discussed are. Those other projects capture better the real circumstances of freedom and choice in shapes reflecting what feels dramatically arbitrary. By contrast, the organicism, the zoomorphism in the Alpine House is pretty. It reminds me of Siza’s Faculdade da Arquitectura and its totemic buildings — an aestheticizing inscription of the body into the form of building. The shifting angles of the sawtooth skylights are like the muscular impression that entasis lends to columns. This aesthetic of the body is antithetical to the non-gestural arbitrariness of shape in the other projects.

SC Entasis was used to restore the absolute proportions and shape of columns that optics in situ otherwise illusorily distorted. It was a means to solve a problem. It excites me to think about it.

RL Whatever entasis was for, why this arbitrary demand for an a priori form or, in the house, a figure? Why should there be any such a priori or external demands? Or rather, it is this very demand which separates this house from the other works that we have discussed, which are not inflected by efforts to correct, to gesture, or otherwise resolve form towards any apparent goal.

SC In the classical, everything was assumed to be in the service of manifesting a priori beauty. Why now should single figuring be applied in a manner similar to entasis?

RL For the usual reasons: part-to-whole elegance, aesthetic economy. Nice as it is, it’s a strategy that skirts the crisis of legitimacy that is addressed in what feels truly arbitrary.

SC Of course, there is no a priori beauty, now.

RL Right. None. So, now, it is strange to see it sought after in the gestural contrivance of this house.

SC Now it is arbitrarily and voluntarily motivated, which doesn’t give me any pleasure.

For you, it’s enough that these unusual single figures seem natural or virtuous when they are synthesized with performance or add an emphasis without disrupting amenity. But that doesn’t explain why they are pleasurable. Are you arguing that when everything is brought into conformity with an unusual shape, this fact, in and of itself, brings about pleasure?

RL What Somol has called shape do not feel like nicely coordinated figures with their well-organized interiors. In the figure, I do prefer the conformity to performance. So, yes, to your question.

SC Yes, but this pleasure you feel isn’t related to the client’s pleasure. It is only an arbitrarily motivated, impulsive tendency of architects to be distinctive or to distill something. And, given all your calls for letting go of the nostalgia for the old dialectics of the pre-entropic city, I would think you would want to let go of the early skyscraper dialectic and its compelling distillation in projects like the Low House. And yet, I am the one who is calling for letting go of it now, in the case of houses. This brings me to what I think Koolhaas’s main projects and the Alpine House are symptomatic of: the skyscraper dialectic, but specifically as it is exemplified by Hugh Ferris. Ferris’s inorganic crystalline massing brought about the necessity to negatively carve out wings, as in the Waldorf Astoria. The final figure was not motivated by Beaux Arts or modern composition. Instead, the city gives us these big pyramidal rocks. And the plans, shaped as alphabetical characters, were ingenious solutions to the problem posed by crystalline formed density and bigness. The Ferris masses were disproportionately deep masses that did not correspond a priori to “best practices” at all scales. The architect is left to try to make sense of these unauthored masses that were far too wide.

RL Not at all scales, but at the urban scale, yes, a best practice idea that impinged on the architecture. But, CCTV or the Casa da Musica, no such thing impinged upon them — not even the demands of lighting a narrow site as in the Alpine House.

SC The impact of CCTV’s figure on the offices wasn’t intended either. You are right of course that the Alpine House differs in that it combines rational purpose plus unintended consequences. The setbacks and need for privacy required it be narrow, top lit, and partly underground. But then, he had to find a way to make a house out of it. In Delirious New York, he didn’t just identify any set of conventions and rules. He identified those that produced strange outcomes, that were not originally intended, and that could be seen not to originate in principled composition.

RL Problem is these rules are often if not mostly gone. As for the Alpine House, following your own argument, the selected forms, unlike those of the crystalline results in Ferris’s work of the inclined plane rule, the house’s forms were derived to serve the needs of the house — not derived from external factors impinging upon it. The Alpine House, then, may be strange, but derived from a logic native to it — quite the opposite of the formation of the Ferris towers, and certainly more legible and conventional than Casa da Musica, which does not begin with conventions of architecture, displaced or otherwise.

SC Yes. Gone. And all he can do is imitate or analogize the idea of outcomes, as opposed to composition. In my view, the stereotomic but unrefined non-compositional carving exemplified by CCTV is an unconscious imitation of Ferris. The association provides evidence of his desire for determinacy as the source for his figures and their ensuing problems.

RL It may be interesting biographically to observe whence Koolhaas obtains the idiom of his work, and it may be an indication of his longing for the circumstances that could produce Ferris’s inventions, but it is still crucial to note that these forces are not what is making the signal works of OMA. Unmoored from such “causes,” what these works now reveal is the absence of such motives, and they do so, not in the manner of the Alpine House, which follows the logical design sequence that you describe, but by resorting to overtly arbitrary shape-making. The arbitrary shapes may demonstrate a longing for externalities forced upon building design, but what they really point to is the absence of such externalities. These techniques are not analogies of what is lost, but indicators of the crisis of freedom that ensues in the absence of conventions and rules, and the longing, protean in nature, for distinction and difference.

SC What gave him pleasure is the understanding that the lithic quality of the Ferris forms was rooted in causes, not prior conventions, principles of composition, or rhetoric. It wasn’t just a stone made available to a sculptor.

RL Whether that is so, the replacement of motivated conditions by unmotivated ones is a profound distinction, and the two are antithetical to each other, regardless of the formal genealogy.

SC Really? Do you accept that I might be onto something?

RL That there is this longing for external forces. But no, it is not what finally these works are about. In that respect, the Alpine House, following from your argument, would be the exception, deriving as it does from solving a motivating problem.

SC Neither the setback rule nor the Alpine House’s adopted sawtooth needed to be represented as solid sedimentary rocks. This is a purely sculptural effect that stands for a process. Koolhaas is fixated on the solidity and opaqueness of Ferris’s form — unrelated to anything inside of it. This house, unlike any of his others, is turned into a ready-made type-form, styled as a crisply carved and uniform sculptural mass. It erupts from the ground and doesn’t even have a door. You have to burrow through the ground to get in.

RL You are comparing the stylistic affectation of the Alpine House to a more substantial distinction in the mineral strangeness of these other works we’ve discussed here.

SC To varying degrees, Seattle Library and Alpine House both synthesize the two sides of Koolhaas: his imitation of NYAC, most clearly executed in the ZKM project, and his evocation of Ferris’s lithic form. Here’s my summary narrative for Koolhaas: he inventively interpreted the necessitated stacking within NYAC to be enabled by the emergence of the elevator and motivated by the culture of congestion; he recognized the necessitated forms of Ferris to be lithic and subsequently carved by architects; and, as a final move, made his own version of these types of forms that are not only non-compositional, but unnecessitated, or what I would call “lithic without a cause.”

RL Yes, but you seem to think that the importance here is the genealogy, reaching back to Ferris. I don’t. To me, the key word in your summary is “styled.” The house is “styled” to mask its more ordinary logic, while the other projects are not. They do not feel like refinements, but rough and unprecedented shapes — arbitrary, strange, without familiar reference.