Go to any major museum to see ancient Greek statuary and you’ll find wall labels that read “Roman copy.” It’s ironic given that modernism taught us that the hallmark of true genius is originality. Yet if the Romans hadn’t copied the Greeks, the Western canon as we know it wouldn’t exist. Many masterpieces bear their mark, as the famed Laocoön and His Sons (c. 42–20 BCE), now believed to a Roman copy — and a much-revised one — reveals. If it had been known as such, its restoration, overseen by none other than Raphael himself, would likely never have happened, nor would the many copies of it, commissioned afterward, exist. The same can be said of the Venus de Milo (c. 100 BCE), another Hellenistic sculpture, if not a Roman copy. Had the French clocked her as a Hellenistic statue and not a classical one when the armless beauty was discovered in 1820, it would’ve languished in the heap of ruins from which it came, given the much-maligned status of Hellenistic art at the time. Buried along with it would’ve been all the future art it inspired, by generations of artists including René Magritte, Arman, Yayoi Kusama, Jeff Koons, and Zhu Cheng, among others. As the oldest canonical work to be continually copied by artists, these appropriations remain as instrumental to the work’s iconic fate as its early misattribution, underscoring again the role of the copy in a canon that’s long denigrated it.

By the early twentieth century, with its cult of the new, that denigration made the copy even more antithetical and provocative by contrast. The ensuing dialectic between novelty and tradition led artists to invent new styles in their wholesale rejection of the past. How odd then that many leading vanguards continued to make copies after masters. Picasso, for example, put out several versions of art’s greatest hits, making works after Velázquez, Manet, Cézanne, and El Greco. Matisse, Dalí, Léger, and others did much the same. Why? Like the masters they were drawn to, these artists possessed a savvy, self-reflexive view of their place in art. They understood that the narrative of modern art, with its cycles of revival and innovation, encouraged this historical positioning. To compare oneself to such masters by copying their work was to elevate and situate oneself accordingly — to define oneself within and against the canon. To that end, artists like Van Gogh, Picasso, Dalí, and later Warhol devoted themselves in their twilight years to studying and copying the masters with whom they sought immortal lineage.

When the tumultuous 1960s ushered in the postmodern era, politicized artists — spurned on by civil rights, the women’s movement, and antiwar sentiment — began to challenge modernist ideals of art for art’s sake, debunking related notions of originality and genius in the process. Canonical appropriation via the copy began to shift accordingly. More than a function of technical study and homage, it became a potent means of parody and critique, and, significantly, the legitimate focus of a sustained practice. Elaine Sturtevant was a pioneer of this approach, though rather than the old masters she took on her peers, to her detriment. Her flawless imitations in the 1960s of works by Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Frank Stella, which she called “repetitions,” were either roundly ignored or censured. Reenacting the work of others to underscore “the politics of image production,” they recalled Duchamp’s readymades and their emphasis on restaging found objects to emphasize the role of context in the reception of meaning. Despite her prescient use of style as medium and subject, which remains pivotal to the evolution of appropriation art, it was too radical for the time. Sturtevant soon withdrew from the art world, and from the early 1970s to the early 1980s stopped making art altogether.

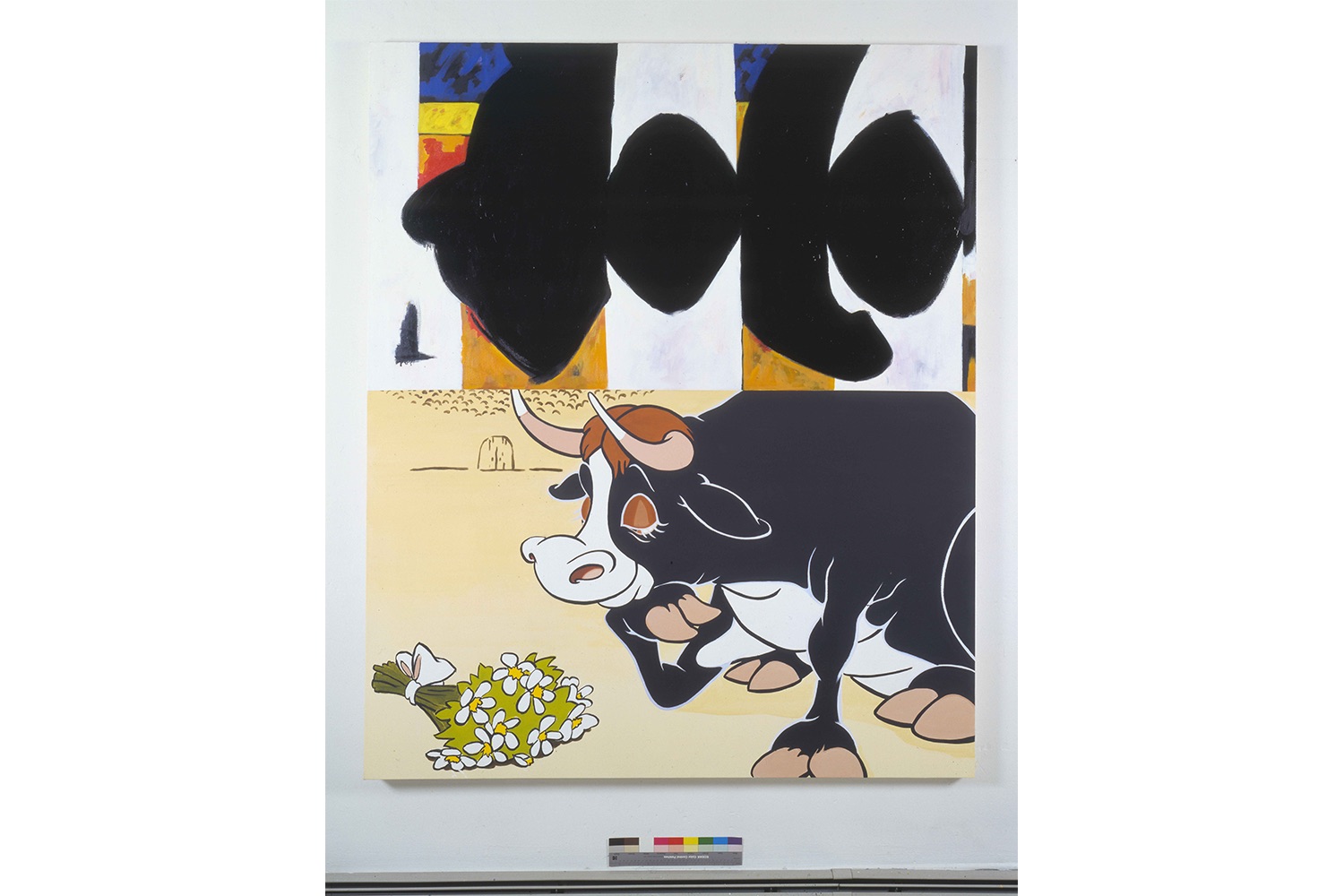

In that interim decade, artists like Robert Colescott took up the mantle, appropriating and quoting canonical works in satires after Manet, Picasso, and Matisse. In contrast to Sturtevant’s implacable mimesis, his insertion of black figures into his versions made them overt and racially charged. His infamous 1978 painting I Gets a Thrill Too When I Sees De Koo, for example, replaces the garish toothy grin and bulging eyes of de Kooning’s archetypal Woman I (1950–52) with a mammyesque caricature. The defacement of one female grotesquerie with another still in circulation at the time was pointedly echoed by the title’s clever word play and reference to racist slang (“de koo” being code for “coon”). Like many related works Colescott produced in the 1970s, the work questioned the originality of the European modernists whose appropriation of African art and obsession with the so-called primitive was fundamental to their output.

If Sturtevant’s impassive “repetitions” were too far ahead of their time, the issues of authorship and authenticity they entangled found currency in the conceptual and media-driven strategies of the Pictures Generation. In particular, Sherrie Levine’s appropriations of canonical male photographers in the early 1980s bore their stamp. Her photographs of work by Edward Weston, Walker Evans, and Alexander Rodchenko were similarly conceived as regenerative acts. Made after reproductions from books and not actual prints, they brilliantly underscored the mimesis already embedded in the photographic medium itself. Not surprisingly, they too were controversial and ambivalently received by critics, but the scandal they caused brought infamy rather than alienation. While Levine described them as “collaborations,” her choice to exclusively appropriate the work of male modernists carried an inherent if discrete feminist critique, exposing, like Colescott, the bias of canonical genius.

Artists in the 1990s were much more up-front. No longer sly or arid, their adaptions treated the canon like a cultural readymade, one inherently malleable and flawed. Moving beyond the theory-laden model of the 1980s, with its exploration of the slippery line between sign and signifier, their relationship to appropriation was personal. The rise of identity politics helped shape this turn as issues of representation in the art world moved from the margins to the center.

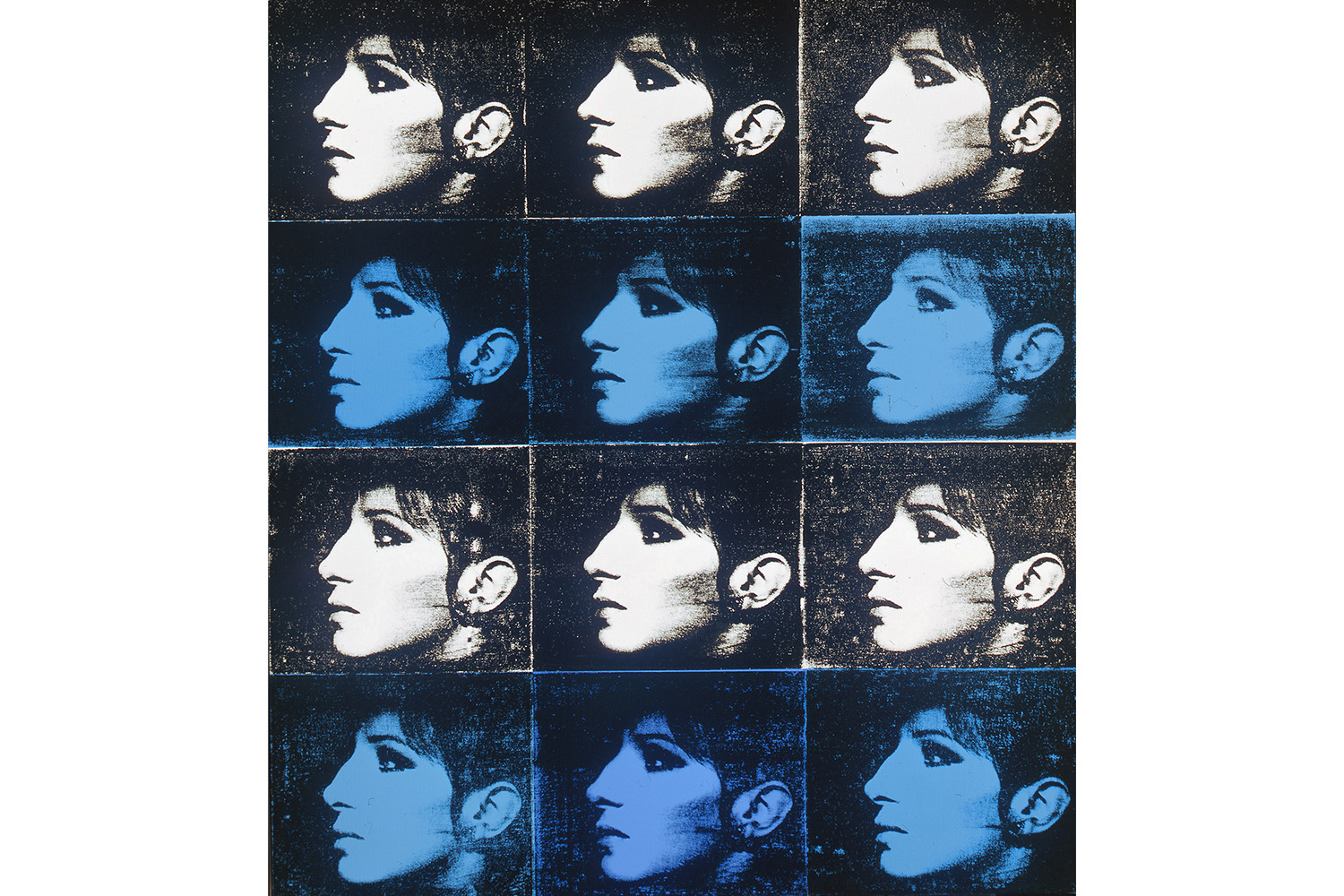

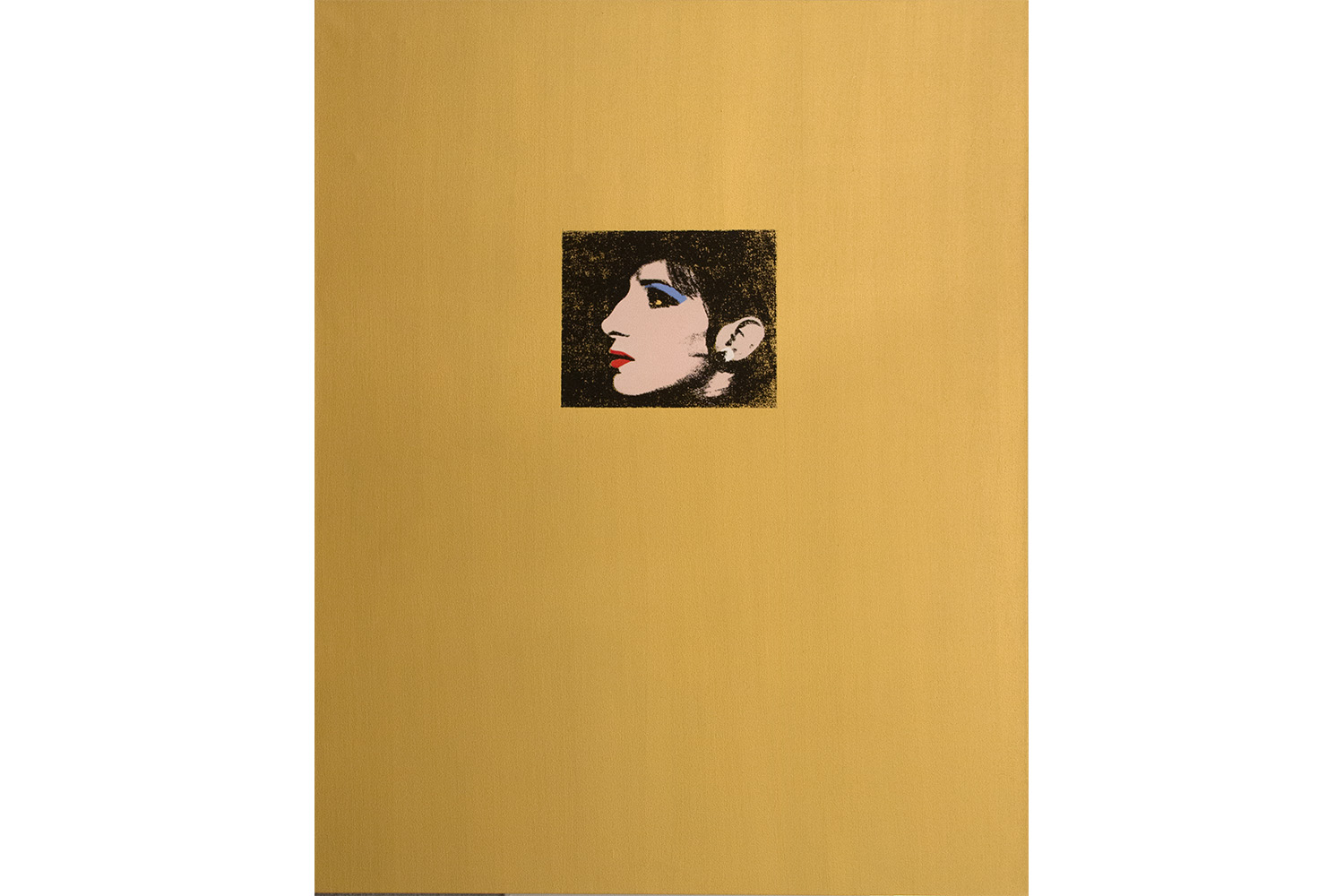

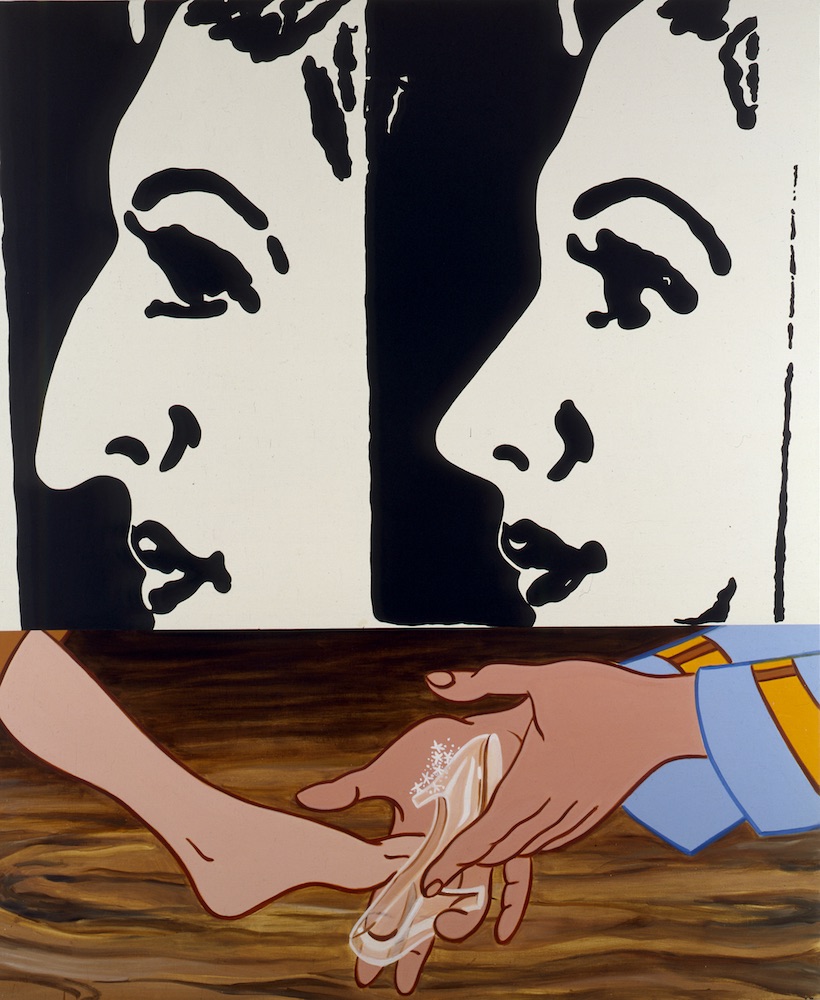

As a result, artists like Deborah Kass, Renee Cox, and Yasumasa Morimura redressed canonical omissions via gender, race, and sexuality in appropriations that offered a provocative form of redress. When Kass started the Warhol Project in 1992, neo-expressionism had robbed painting of its radical potential. She refused to equate the message with the medium, and, in a desire to salvage the prospects of painting for a feminist agenda, launched her seven-year project. Her rendition of Warhol’s “Jackie” series (1964), titled “the Jewish Jackies” (1992), encompassed both her love of pop culture and its problematic relationship to gender, ethnicity, and sexuality. By transposing images of Jackie Kennedy with those of Barbra Streisand, the works deconstructed notions of beauty and glamour via the male gaze that, as a Jewish lesbian, had impacted the artist growing up. Though the two pop culture icons had become famous at the same time, Streisand’s inability — and refusal — to assimilate to white Anglo standards of beauty made her unworthy of the same worshipful status, and consequently Kass’s hero. The artist’s emotional identification with the diva as an icon of difference is thereby essential to her critique, as is its seminal and unabashedly queer gaze. By creating a signature style that was entirely Warholian, like Sturtevant and Pat Steir — whose “Brueghel Series (A Vanitas of Style)” (1982–84) was a touchstone for the artist — she underscored modernism’s alignment of gender with style. In doing so, she ironically made a name for herself.

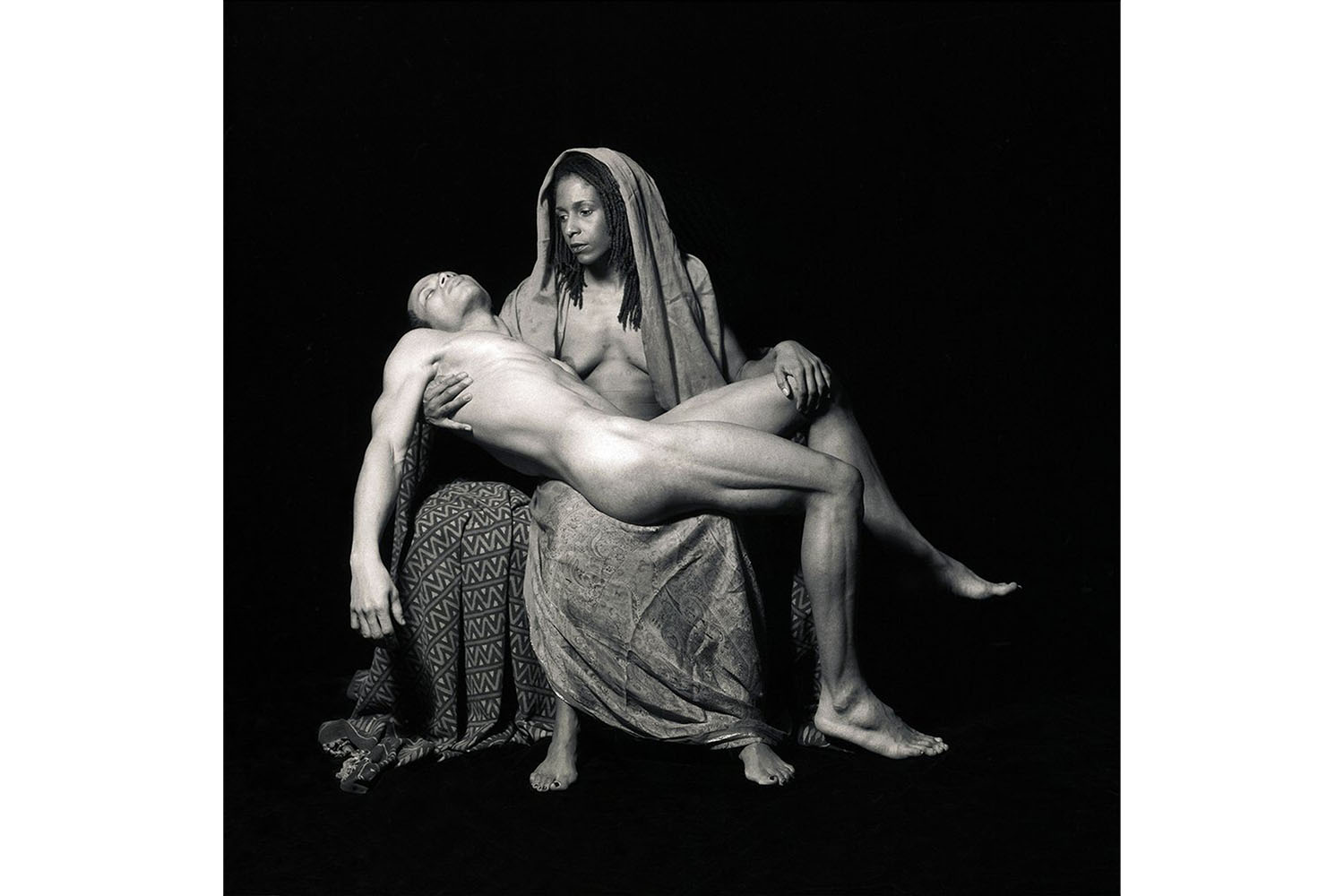

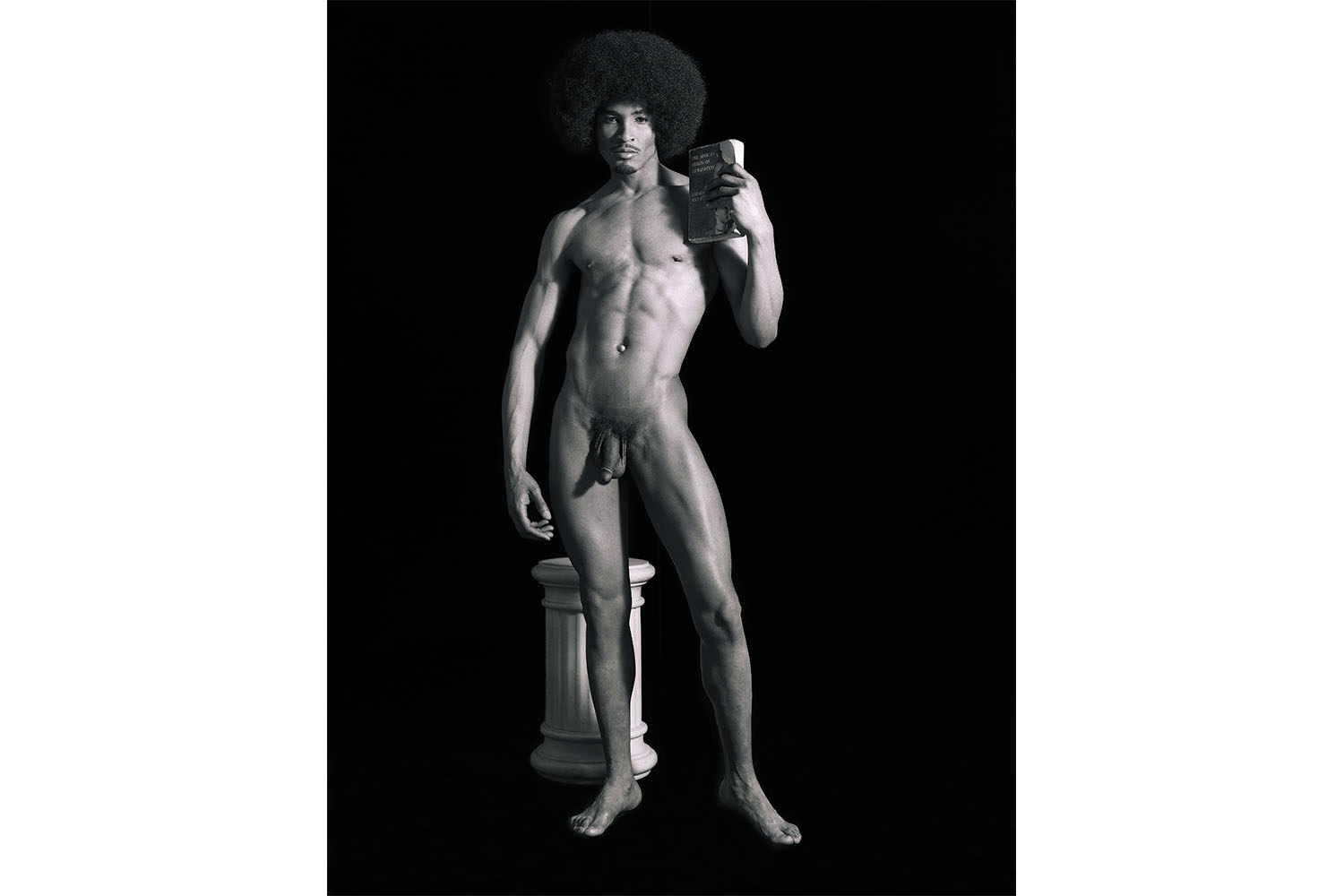

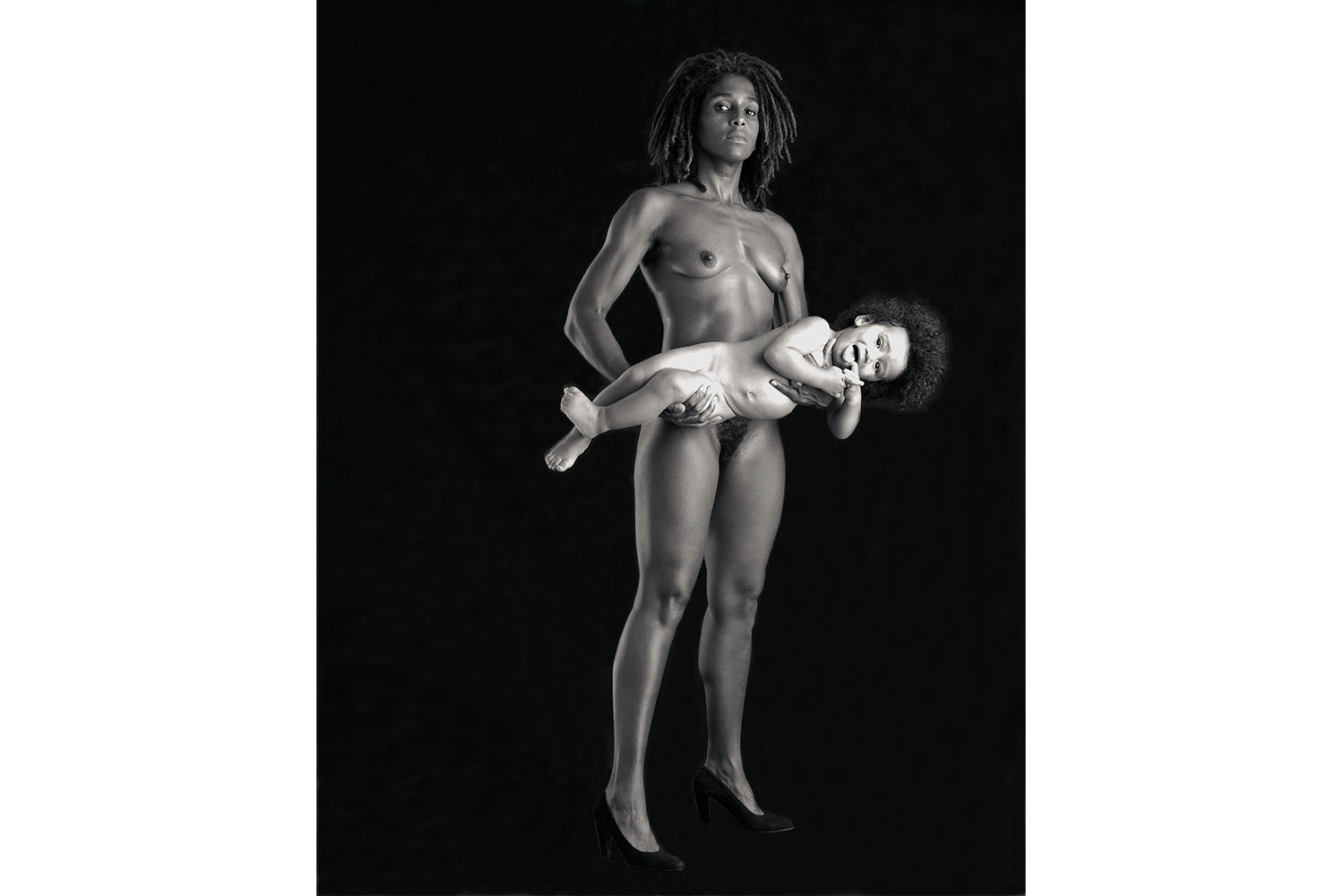

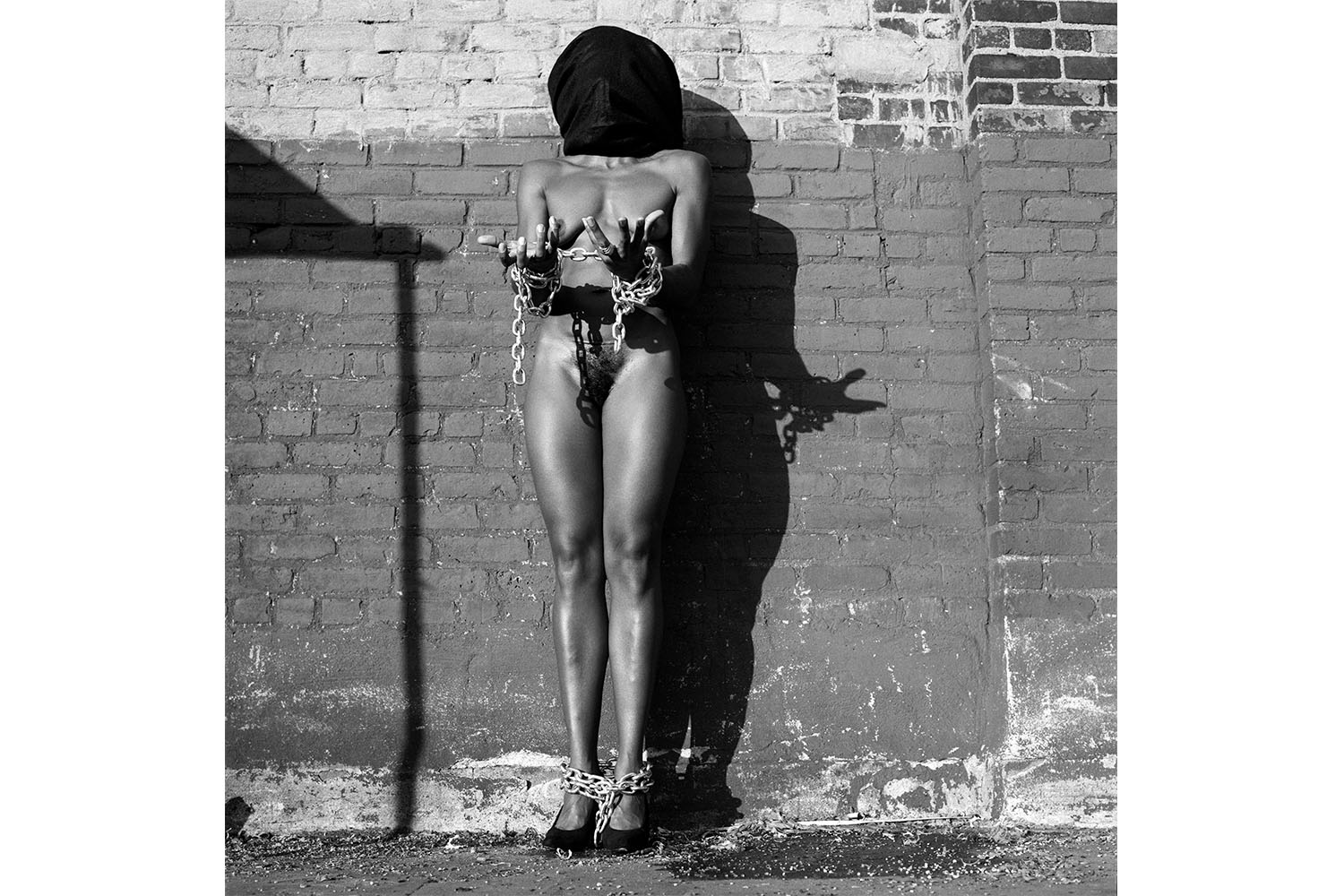

In a similar vein, Renée Cox’s photographic series “Flippin’ the Script” (1992–96), which revamped religious masterpieces from the European tradition, helped catapult the artist’s career. The life-scale diptych Origin (1993), which borrows its subjects and monumentality from Michelangelo, consists of two panels: Yo Mama, which evokes both his Pieta and Madonna of Bruges (1501–4); and David, after the Italian master’s David (1501–4). Although the two works were made to be shown together, the black-and-white diptych only recently had its public debut in 2019. Yo Mama, included in Marcia Tucker’s 1994 exhibition “Bad Girls” at The New Museum (under the title Mother and Child), depicts the buff artist standing nude in heels as she holds her toddler son close, his body — also unclothed — posed horizontally. The self-portrait, shot from below, imbues the artist’s gaze with a resolute authority that resists Mary’s characteristic humility. In addition to her desire to “introduce people of color in these classic scenarios,” the work took on prevailing views in a white, sexist art world that devalued motherhood. David, the second image in the pairing, featured an equally fit black male nude with a similarly confident stare, his contrapposto stance mimicking the Renaissance marble’s sensual lean. In his left hand, held up near his face, is Cheikh Anta Diop’s groundbreaking 1989 text The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality. Like Colescott before her, Cox’s David, so altered, functioned reparatively, gesturing to an iconographic past buried by the legacy of slavery. That it was Cox’s spectacle of a towering black male nude as a proto-Adam that kept the diptych from public view simply underscores its symbolic power.

If there’s any artist to emerge from the 1990s multicultural zeitgeist as a progenitor of the copy as a sustainable practice, it is Yasumasa Morimura. For more than three decades, the Japanese artist has made works after those in the Western canon. His deconstruction began as early as 1985 with his best-known series, “Daughter of Art History,” in which he painstakingly recreates paintings by famous artists — Van Gogh, Vermeer, Duchamp, Frida Kahlo, etc. — by photographing himself costumed and made-up amid painted backdrops. Theater A (1989) remakes Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), giving the nearly century-old work a facelift of sorts. Honing in on the barmaid at the heart of Manet’s late painting, the artist replaces her forlorn face with a powdered and rouged version of his own. Like the wig he wears, the attempt to assimilate or “pass” — as white, as female, as European — is set up, quite literally, to fail. Instead, through the artifice of drag, Morimura conveys the impossibility of a gay Asian man finding any version of himself therein. The failure is made all the more hyperbolic by the surreal montage of Morimura’s crossed forearms and clenched fists — their skin tone darkened here rather than lightened — that burst out of the maid’s bodice.

It’s an apt metaphor for the whole enterprise of canonical appropriation, a practice that has only proliferated in the twenty-first century as the canon diversifies. From Marina Abramovic’s Seven Easy Pieces (2005), in which she reenacted 1960s- and 1970s-era performances by peers — including Joseph Beuys, Vito Acconci, and Valie Export — who, like herself, are now part of the canon, to Kehinde Wiley’s masterful renditions that rival and usurp his neoclassical sources, the role of the copy renews itself with each generation. Just ask the Greeks.