Michael Abel: First question — how does Volumes begin?

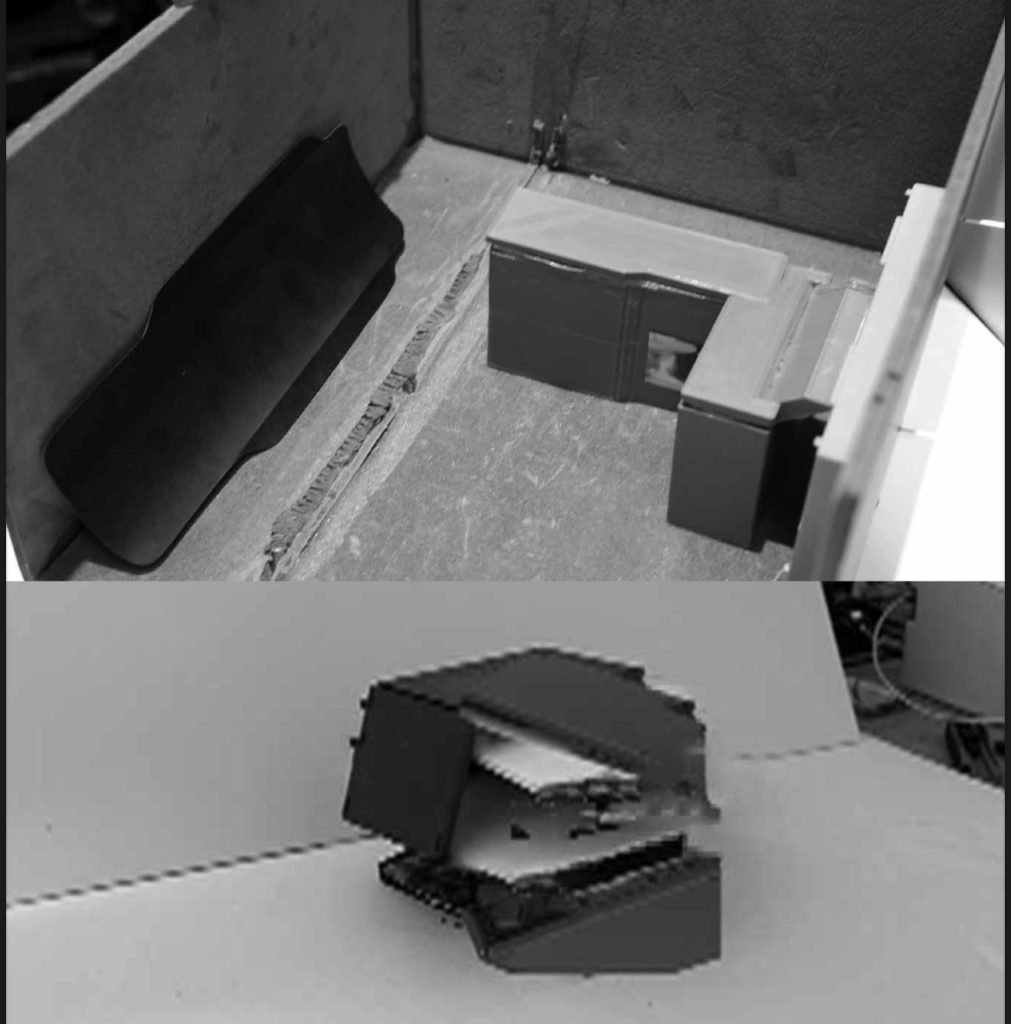

Luigi Alberto Cippini: What I tried to do, within my limitations, was to make something about stalking — architecture should be more extreme. Stop e-flux, stop Casabella, stop everything. Just print nonsense — low-resolution JPEGs of things you love. Write a critical text about it, or a poem, or a song. Then, make the most of this platform to create the shift you feel architecture needs —something that can reenter general culture, fashion, and broader society. It needs to be liked by the burning minds of fashion. That said, if you look at our themes or buildings, they were incredibly anal — highly specific, deeply engaged in noisy, hyper-specialized research. But the way we treated them was completely different: “Fuck you. That’s it.” I still believe you can create architecture rather than just create a new office.

Nile Greenberg: Our theme — “Crisis Formalism” — has a lot of overlap with yours, “Anti-Composition.” What interests me is the disciplinary critique. I think each of us understands it differently. Luigi, I think you see the discipline as dead, or as an accelerationist, speeding up its downfall. I see it as nearly dead and needing to build it back up by reintegrating crisis and form. Maybe Michael still believes disciplinarity exists?

MA I don’t find it productive to be so polarized. I’d rather take the good and leave the bad. But disciplinarity? It’s fine.

LAC Can I say something stupid? I don’t even know what disciplinarity is anymore. When every architect is drawing pink lines and nonsense diagrams, and what we actually build just looks like architecture, they’re all so happy to be part of this general statement — where everything needs to announce itself as architecture. And yet, the entire process — how it’s done, how it’s communicated — is the most boring, useless, and pedantic way possible. So honestly? I don’t give a fuck about discipline anymore.

MA The fact that you reject it actually proves you are disciplinary. Maybe you’ll be remembered for doing something different. But honestly, nobody cares about the people drawing pink lines —that’s an old trope. Nobody even talks about that anymore.

LAC The real issue is that whatever people do is so rigidly designed to fit into a communication compromise — a way to appease the small group of people who actually need the information to build the thing. And over the last ten years — aside from a few extreme cases — the built environment has become just architecture. In cities, we have buildings — just buildings — and then we have things we call architecture. And the presence of architecture, whether in cities, magazines, or construction sites, is fading. Because no matter what, when you try to create something new, what you’re really doing is achieving a kind of edgy compromise — just enough for people to recognize you as an architect, to say you’re “doing architecture.” But all that means is you’re coordinating your language, your subjectivity, your economic production with the general statement of the city. Right now, the city is built by buildings. In some rare cases, it’s built through architecture. I need the discipline to stop acting like a snobbish family reunion and start behaving like the drug-addict punk daughter — the one who, no matter her heritage, will do whatever it takes to be free again.

MA Let’s be real — punk daughters usually come from extremely wealthy backgrounds. Maybe this is just a stupid semantic debate because, honestly, right now we’re literally creating discourse, and frankly we’re getting old.

NG It is relevant. To you it’s semantic because you think the discipline is still operating. The reason our Armature Globale’s work is relevant — the path we’re on too — is because mediums, including architecture, have collapsed. No single medium has enough power to express something fully. There’s no longer authorship in a single medium. No single format can carry enough weight. Architecture doesn’t exist as a medium at the moment. Its failure is closer to a “cry for help,” an attempted suicide. It’s seeking an act of faith and love — waiting for us to reconstitute it as a new body.

MA People keep trying to separate buildings from architecture. But what if buildings are architecture, and then you use other mediums to describe them? That’s what we call architecture. It’s not that complicated. It’s like painting —anyone with a brush and a surface can make a painting. We’re in a building, and then we use other mediums to describe it. That’s what architecture is.

LAC Exactly. The medium is the brush. You can be like Blinky Palermo and paint a wall — or you can paint a building. The surface itself is irrelevant. What matters is who is doing it and why. There’s no real “collapse.” Everything is always in flux — constantly being destroyed, rebuilt, and reshaped through new mediums and new ways of communicating. The point isn’t whether something is architecture or not — the point is what we do with it and how loudly we say it. That’s what discourse is for. Whether it’s buildings, architecture, magazines — it’s all the same. For me, I don’t waste time critiquing the process. My approach has always been what I call “suicidal modernism” — a kind of reckless modernism where you just do things without overthinking. Instead of getting caught up in theoretical debates about, say, computational realism or 1920s structural patterns, I’d rather focus on making architecture that feels foreign — something outside the discipline. Being on the outside is more powerful. You don’t need institutional validation. You don’t need to be perceived as part of the discipline. You can influence things by simply staying a little outside. I feel connected to your practice because I see what you’re trying to do. But what interests me more than texts or critiques is the process — how you act as a studio, almost in a pop-fanatic way. Your buildings will be interesting, but they’ll also be shaped by the discourse you generate around them. It’s like against the politique des auteurs in French cinema — where the work is separate from the author. I believe in extreme subjectivity, in pushing things to an extreme. Architecture, when in progress or still under construction, becomes a kind of diluted medium — where critique and theory exist in fragments, embedded within the work itself. And that’s what makes your studio so fascinating. The way you use it as a platform — not just to design buildings, but to communicate what it means to be an architect today. I’d rather look at buildings that might be so-so but come from real, honest reflection about the limits of being an architect in New York —than admire a beautiful, empty formal language. What you’re doing makes architecture feel contemporary, aligned with what it means to be alive in 2025. And that’s the way forward. In the end, the goal is to make buildings that truly belong to our time — edgy, engaged, aware. Not in some localized, superficial way, but in a way that understands what being contemporary actually means. And I think, eventually, we’ll get there.

MA What we’re saying is simple: the dominant discourse is all about crisis, but no one talks about its formal implications. Everyone fixates on doomsday scenarios, and we just wanted to ask: What does that look like? From the moment I saw your work, I was seduced by it. And I think your work is a reaction to this constant sense of impending collapse. We’re reacting to it too, but differently —as we should. We tried categorizing how this crisis is manifesting in form. One category is “Collapse,” which might align with “Anti-Composition” — would you say? Another is this “Repair Language,” like Brandlhuber or 51n4e. And then there’s “Form Follows Forces” — which is basically Bjarke Ingels. Honestly, it’s that whole “climatic force changes the angle of the building” thing — super dumb, but it works. We’ve also been obsessed with Preston Scott Cohen. He does it better, but he doesn’t care about politics. Have you ever seen his Tel Aviv Museum of Art?

LAC No, not yet. I was into his work for a while, but not recently. Still, I love everything in architecture — I enjoy what’s happening, even if it’s media-trained nonsense. He had a small footprint, kind of like Doxiadis but pop and stupid, like Bjarke Ingels. Bjarke is like Doxiadis in the sense of presence — backed by power, everywhere, but ultimately making blockbuster architecture. Like playing PlayStation. And I love that. One of my favorite buildings in New York is United Nations Plaza by Roche. It’s this mix of trashy, vulgar, formal chaos over the city — the one with the skyscraper cut through the middle. And the building Bjarke Ingels did with a skyscraper with a courtyard cut through in the middle…

MA Insane. One of the best buildings in New York.

NG I was in a taxi in New York, and the driver told me his son lives in this “disgusting” building, but apparently architects love it.

LAC Also, the Maritime Museum — it’s underground. It’s like Michael Bay in architecture, and I fucking love Michael Bay.

MA Better than Rem?

LAC Formally? I don’t know. Rem’s uber cool. He’s done everything that needs to be done and everything no one has dared to do. Unbeatable — for now. But I don’t have idols. I treat everyone as competition, though I still enjoy their work. I’m self-sufficient like that. NG And America?

LAC I love America. I pitched a project on Lafayette Street in NYC — a five-story concrete-and-glass building. Also I did one in Miami. I can’t wait to build in the US because it’s just built trash. And I love that.

MA Do you fetishize trash? Do you want Milan to be more trashy?

NG Milan is very vulgar — authorship and taste are superfused into the morphology of the city. In the city planning itself there are far too many roads.

LAC Milan is fucked. I love America because everything there is violent — even its buildings. The only way to make good American architecture is to not be American. I can’t wait to do that myself, to be an American architect. But Milan is trash, and we’ve been trying to build here for years. It got so boring — redoing existing buildings, working with clients who were also bored. So last week we said, “Fuck it.” Let’s stop adapting to the built environment. Let’s just buy things, describe them, and build new. We’ve embraced a new mode: nope form. Meaning, we’re doing whatever it takes — extreme, direct — to make architecture. Milan, honestly, is just a loop of people hyped on fashion, cocaine, and art. That’s the reality.

MA There’s definitely a strong crossover. Fashion has infiltrated everything.

LAC Yeah, but beyond that, Milan is boring. It feeds on itself.

MA Los Angeles feels like a city of the future right now.

LAC Exactly. We’re trying to build things that feel transnational — buildings that just happen to be in Milan, but could exist anywhere. More about the future of architecture than the city itself.

MA I’m a New York Critical Regionalist.

LAC I am a Sagaponack Critical Regionalist.

NG New York is bureaucratic form more than trash at the moment. It’s hard to define it beyond rules, codes, and zoning. It’s less a formal identity based on zoning forms like Sol LeWitt or Hugh Ferriss and more based on process engineering.

LAC I love this old book — it’s thin, yellow, full of weird projects like Jesse Reiser’s bachelor flat and these insane garden-fence buildings. It captured a raw energy before they all moved into academia and started building trash. But that’s America — completely contradictory, and I love it.

NG Why does architecture always operate at the state-of-the-art?

LAC Absolutely. We call it “total warfare” — architecture should engage all levels of society, but in a fun way. It’s unrestricted happy warfare against everything, using every new technology possible.

NG Funny you say that. War kept coming up at a conference, “Utopia and Psychopathology,” on Anthony Vidler.[1]“Total war” was the basis for the avant-garde, the Smithsons, the Eameses… But the West hasn’t seen a “total war” in a hundred years, just asymmetric ones. Asymmetric war is all about sustained power, ongoing and only procedural. That lack of symmetry has trickled into all forms of mediation, into everything — bureaucracy, data, insurance, logistics. Architects have become coordinators…

LAC That’s why every project should be an act of creative terrorism. Happy warfare means everyone does whatever they want for maximum impact. At some point, that changes things. I fought to publish dark, blurry images of my projects when everyone said it wouldn’t work. Now that it’s accepted, I’ll switch to beautiful ones. It’s about negotiating freedom within the system.

[1] “Utopia and Psychopathology: A Symposium in Honor of Anthony Vidler,” Organized by Beatriz Colomina, Spyros Papapetros, and Mark Wigley, Princeton University School of Architecture, November 7–8, 2024.