“Träume scheinen mir wie Orchideen – / So wie jene sind sie bunt und reich” (“Dreams appear to me like orchids – / like them, colourful and rich”). – Rilke, Der Traumer (II), 1895

In art history, the orchid has always been the uncanny flower. Unlike the lily or the rose, it never carried a fixed Christian symbolism; even its name, from the Greek orchis (“testicle”), encodes an erotic undertone. With the colonial orchidelirium, or ‘orchid mania’, of the nineteenth century, the bloom became a trophy of empire: fragile, decadent, impossible to cultivate without hothouses and capital. Later, from Art Nouveau ornament to Georgia O’Keeffe’s abstractions, the orchid signified sensuality, excess, and strangeness, depicted as a flower of luxury and desire but also of morbidity and fetish.

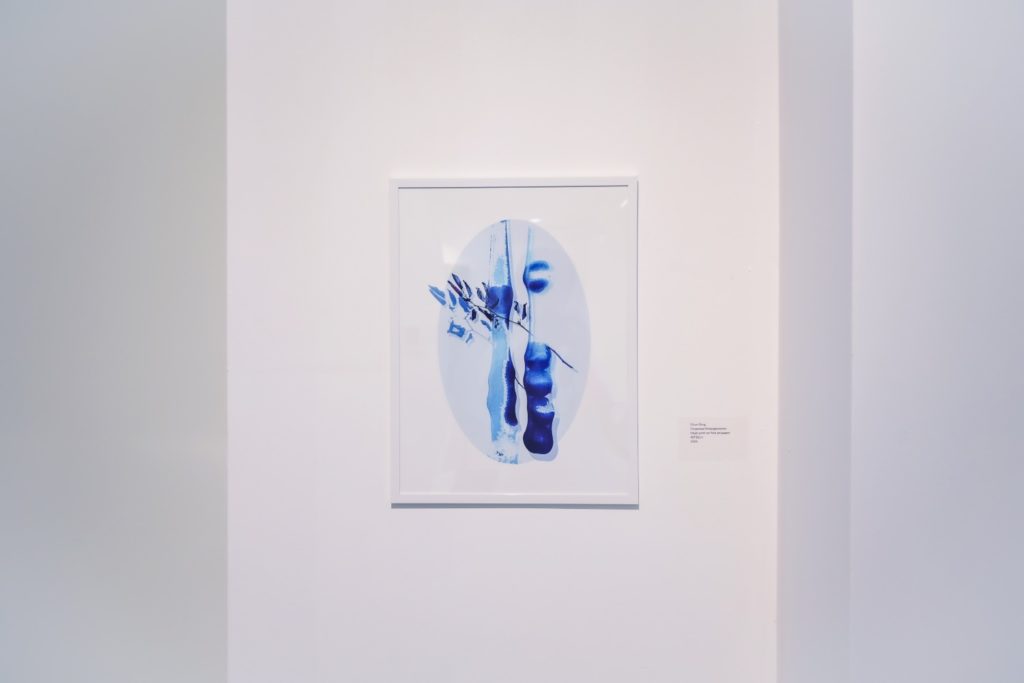

This unstable history makes it an apt material for Chun Ding’s Corporeal Entanglements (2025) and Orchid Atlas in Reversal and Phase (2025). In these works, Ding pulls the orchid out of museological taxonomy and spectacle in order to re-stage it as an image of reversal, fragility, and entanglement.

The cyanotype, with its reliance on light and shadow, already materialises this dialectic. Corporeal Entanglements builds on Ding’s use of the method as a site of emulsion, a blurred boundary between not only historical/traditional techniques and emerging visual technologies, but between body and environment. The work layers a fragile plant cutting against two vertical columns of suspended forms – fruit or spheres encased in a translucent sheath, suggestive of stockings or stretched skin. The effect is both bodily and architectural; we are somewhere between blueprint and x-ray, the fruit becoming organs, the columns becoming limbs. This submerged anatomy hovers between specimen and apparition, held at the threshold between diagram and dream.

Much like Rilke’s orchids, Ding’s images exist “between worlds” as translucent, unfixed, layered dream-objects. In Orchid Atlas in Reversal and Phase, she presents the orchid in paired inversions: upright and inverted, positive and negative, ying and yang. The cyanotype process extends the poetics of superimposition. A cutting is set against biomorphic blue structures that suggest bone, scaffold, architectural frame. Both panels refuse the authority of the traditional lithographic plate via Ding’s decision to stitch the prints into fabric – the image of a plant pressed onto a surface made itself of natural fibres. In Baudrillard’s terms, it becomes a textural sign, a semiotic gesture revealing that depictions of living things do not merely represent the Real but substrate them into their own image – literally, in the case of atlases, sites of knowledge wherefrom cartographic diagrams and botanical plates have long shaped the terms of encounter with land and life.

Ding’s cyanotypes ultimately resist the fantasy of mastery, whether through taxonomy or technology. In Der Traumer (II), orchids are said to draw from aus dem Riesenstamm der Lebenssäfte (“the giant stem of life’s sap”). Corporeal Entanglements and Orchid Atlas in Reversal and Phase’s orchids operate in this same register of fleeting intensity, drawing strength from their substrates even as they slip toward dissolution. The boundaries between presence and withdrawal, material and apparition, taxonomy and trace remind us as Rilke does that orchids – like dreams – belong to the interval between life and image.