At M Leuven, the solo exhibition “A History of Touch” by German-British artist Grace Schwindt offers an unusually intimate encounter with the past. Schwindt invites us to approach history through the senses: through touch, closeness, and care. The exhibition is the result of a residency the artist undertook in 2023 in the museum’s storage and conservation facilities, during which she observed how damaged historical sculptures are stored, handled, and preserved. What emerged is a deeply felt and conceptually rich body of work: poetic, precise, and quietly transformative.

M Leuven has a long tradition of engaging its historical collection in meaningful, contemporary ways. The museum previously invited American artist Jill Magid, whose 2023 two-channel installation The Migration of Wings followed the complex trajectory of Dieric Bouts’s The Last Supper (1464–68), a major work of the Flemish Primitives.

From the basement cloakroom, I take the elevator to the second floor and cross the beautiful open gallery to enter the room where “A History of Touch” is on view. Schwindt’s residency in the museum’s storage depot inspired a profoundly emotional response. She became fascinated by the careful, almost reverent way these broken objects were handled. The museum staff, headed by Benedicte Dierickx, didn’t treat them as ruined or useless, but as delicate carriers of meaning, worthy of preservation and gentle attention.

That sense of tenderness runs throughout the exhibition, which is carefully curated by chief curator Eva Wittocx. At its center lies the work that shares the exhibition’s title: A History of Touch (2024), a six-part glazed “ceramic landscape” (as the artist calls it herself) created to support and house a single sculptural fragment, one leg from a sixteenth-century depiction of Christ on the Cold Stone. Schwindt chose not to restore or recreate what was lost, but to build something new around what remains. Using 3D scanning, she shaped ceramic forms that cradle the leg fragment, and suggest – through absence and contour – the body that is no longer there.

The work is quiet but powerful. It invites viewers to lean in, to take time, to feel – figuratively. In doing so, it sets the tone for the entire exhibition. The main gallery space has been divided by cross-shaped walls, creating four smaller viewing areas within the larger room. The layout feels appropriate: a subtle reference to Christian iconography, but also a way to slow down our movement, to shift us into a more contemplative rhythm.

As I move through the space, I am struck by how many of the works are about fragment: never whole bodies, but parts. Torsos lie horizontally, as if resting. Schwindt was inspired by the way sculptures are stored in museum depots: not standing upright as we might expect, but lying down, cushioned, carefully protected. That posture – vulnerable, passive – repeats across her large-scale paintings, her watercolors, her sculptures.

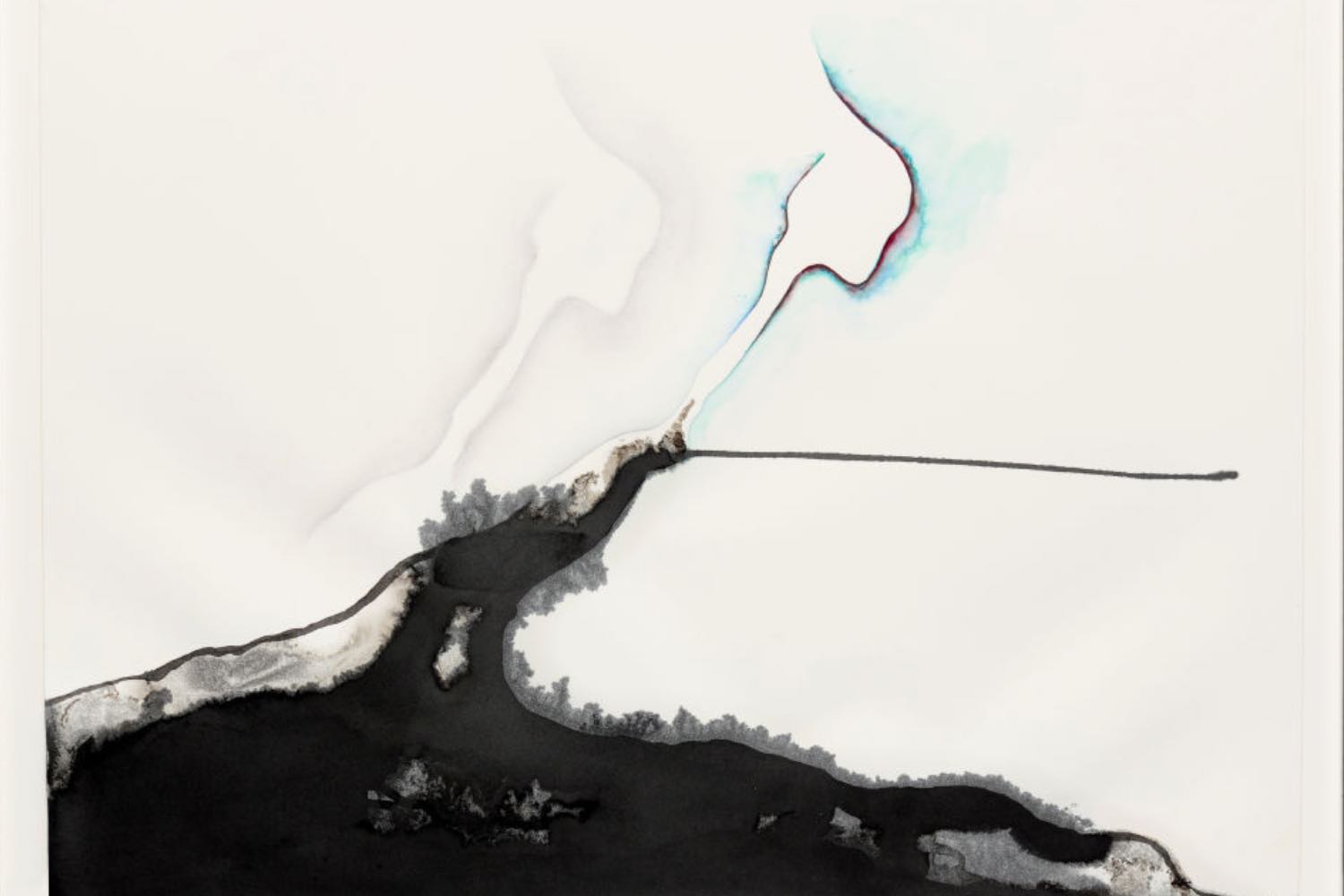

While I’m looking at the piece When A Body Becomes A Landscape (2024), a gallery attendant approaches me. “Did you see the face?” she asks. At first, I’m not sure what she is after, but I indeed did see it: on the right side of the painting is a vague, shifting face that seems to emerge from the texture. It’s barely there, just a suggestion. But when you see it, it stays with you.

This is what Schwindt excels at: drawing our attention to what we almost overlook. In her drawings and watercolors, she often focuses on the overlooked aspects of sculpture: cracks, scars, backsides, negative space, fractures. She captures not the polished front, but the places where history has left its mark. In doing so, she transforms damage into narrative.

Scattered throughout the room are smaller sculptures combining human, botanical, and animal forms. A leaf rests gently against a head. A bird figure perches quietly. In Touched (2024) and Becoming a Flower (2024), human and vegetal shapes merge. There is always a sense of care, of contact, of beings leaning into one another, resting together. Vulnerability is not framed as weakness here. On the contrary, it is shown as a site of strength, healing, possibility.

Schwindt’s work asks urgent questions: How do we treat things – and people! – that are broken? What do we value in a world obsessed with wholeness, productivity, and perfection? Is there a beauty in fragmentation, in the evidence of time?

Her approach resonates with the museum context, but also far beyond it. In a time when the world feels increasingly fragile (socially, politically, environmentally), “A History of Touch” proposes an alternative way of seeing: slower, softer, more attentive. It asks us not just to look, but to care for what we are looking at.

This is not an exhibition you walk through quickly. This is one that asks you to pause. To notice. To feel. And, ultimately, to imagine a world where tenderness is a form of resistance, and care is a way of understanding both art and life.