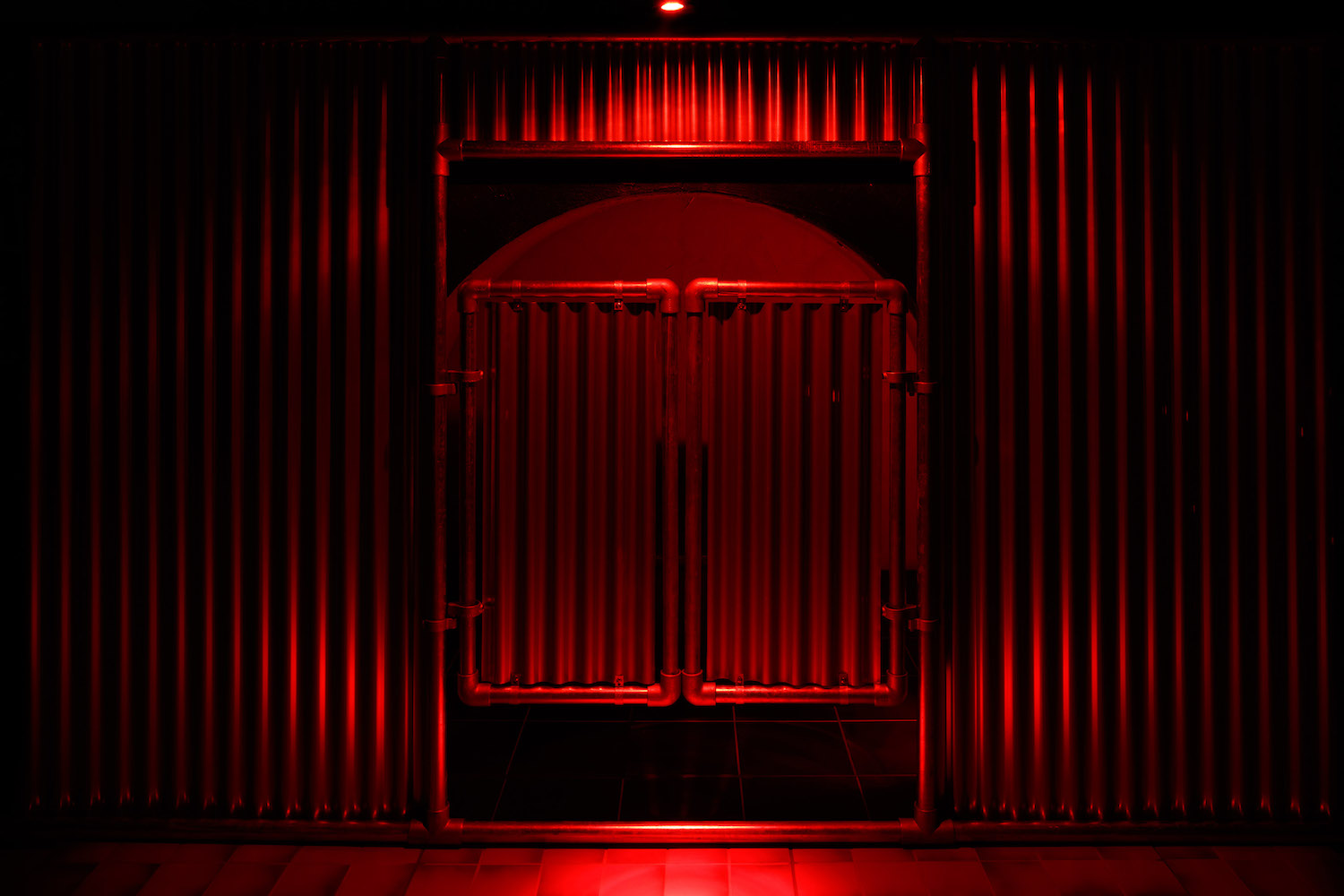

At the end of a concealed cobbled mews, hidden behind London’s busy Dean Street — known for its sexual health clinics and members’ clubs — a thick black door stood ajar, letting through a red glow. Inside, a long narrow corridor was enveloped in corrugated steel sheets and paved with shaded tiles, punctuated by red LED lights that guided visitors through to the end of the space. To the left, a young, seemingly able-bodied white male was collapsed on a square black plinth, motionless, surrounded by a rolled up white T-shirt, a leather wallet, and some coins.

The unsettling performance was part of London artist Prem Sahib’s immersive installation “People Come & Go” (November 13–30), with elements based on the interior of a nearby cruising club. It was the first of three exhibitions in a series titled “DESCENT” at Southard Reid, of which the third is currently on view. Like much of Sahib’s work, it deals equally with pleasure and exclusion, embodied within architectural forms and devices that often evoke minimalist aesthetics, oscillating between the permissible and the unbearable.

The dislocation of cruising practices and histories is an ongoing motif in Sahib’s work. In 2017, he salvaged a series of 12 lockers from the now-defunct Chariots bathhouse in gentrified East London, and temporarily reterritorialized them at the Kunstverein Hamburg, Germany, where he had a solo show (they have since been acquired by the Tate collection). Most recently, in the summer of 2019, he staged a one-off, site-specific performance at the archeological site of Pompeii, curated by The Fiorucci Art Trust. Titled simply Cruising Pompeii, it featured half a dozen local men walking up and down colonnades in the Villa of the Mysteries, performing cryptically stylized routines with their arms, guided by iPhone lights and accompanied by the noise of a motorbike outside the site. By contrast, the confining atmosphere at Southard Reid’s opening exhibition was daunting. There — wherever that was — desire felt equally bullied by memory and hope, removed from the utopian ideals of queer futurity we were once promised.

Fast forward to the second leg of the exhibition, titled “Cul-de-Sac” (December 5–21, 2019), and we appear to finally transcend the “here and now,” diving instead into Sahib’s own psyche. The first section of the show focused on a series of press clippings and other archival material spanning the late 1970s and the 1980s (the decade Sahib was born in) spread across a display case. They belong to the artist’s uncle, a community worker whose activism involved HIV prevention and advocacy on behalf of the local youth of Southall — a South Asian hub of West London — who, we learn, were regularly subjected to police violence. Meanwhile, projected onto a wall at the back of the gallery space were images of Sahib’s childhood street, shot with a drone that falls from the sky into the familiarity of suburban scenery: a nod to the double meaning of the series title.

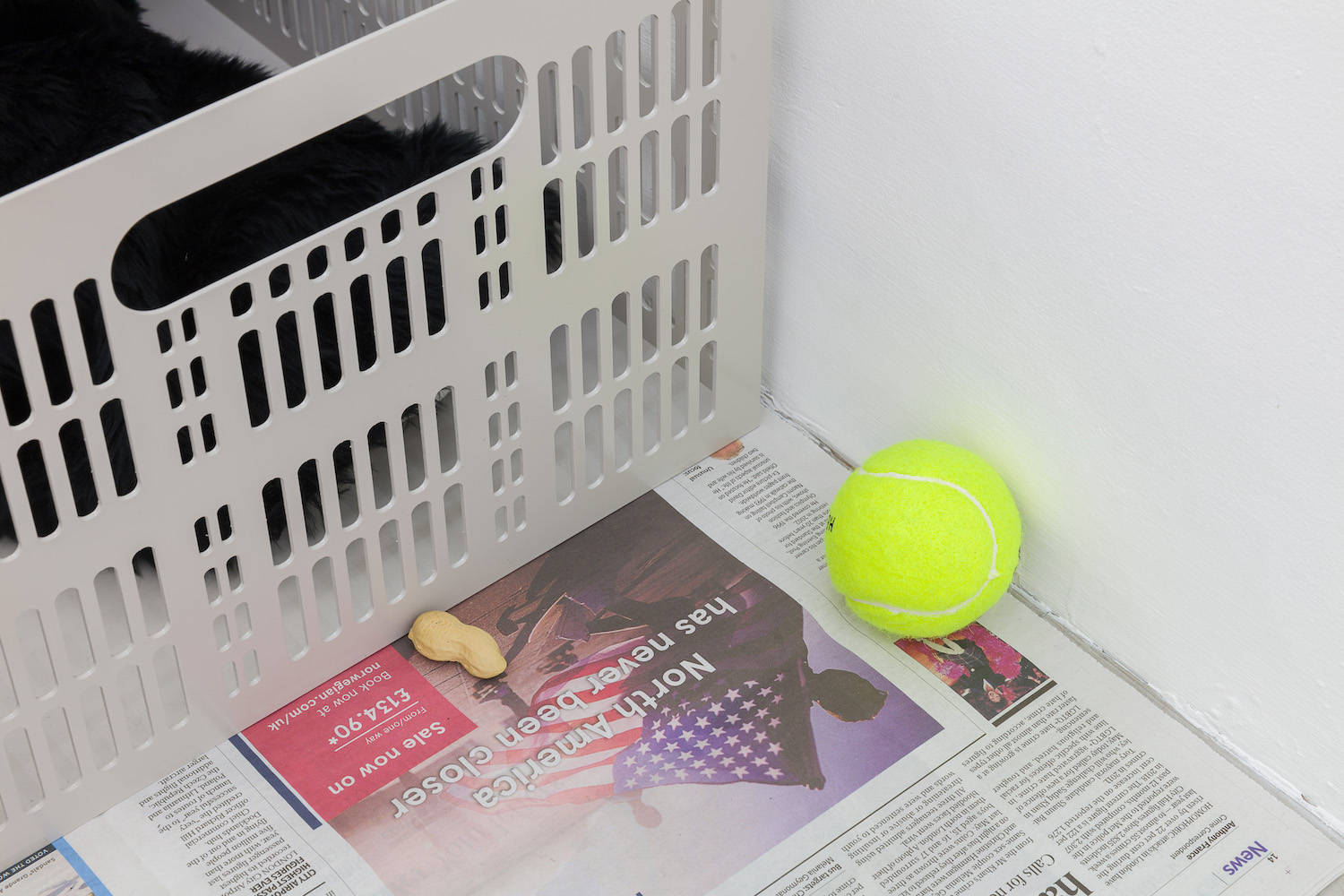

Now, the freshly opened third and final show, “Man Dog,” throws us into the uncertain sphere of the possible. It is titled after its central piece: a black, obsidian mirror sculpture converted into a speaker. Occasionally interrupted by otherworldly sound effects, we can hear an American man verbally abusing the artist in a monologue recorded from Chatroulette, a video chatroom predominantly used by men for the purpose of masturbating on camera. “I don’t care if you’re even human,” the man concludes, after delivering an impassioned speech fueled by nationalistic sentiment, enforcing borders on the otherwise virtual territory of the chatroom. Other works include three still-life arrangements reminiscent of pet beds placed on newspaper, from which sensationalist headlines (all dated from 2020) radically contrast with the press material featured in the preceding exhibition. One of them reads: “Woman, 21, posed as skater boy to groom and sexually assault girls,” reflecting the mainstream media’s perpetuation of “gender fraud” narratives.

But the exhibition’s most intriguing and, arguably, conclusive piece is one titled Beneficiary: a sculpture composed of eight, life-size legs — like those of a spider — made of white plaster and wrapped in identical white socks and nondescript white trainers. They stick out from the bottom of a faux wall, like an indistinct, anthropomorphic mass in a state of perpetual revolt. In a Deleuzian reading, a process of becoming-animal is underway: much like that of Kafka’s protagonist Gregor Samsa who, in Metamorphosis, wakes up one morning transformed into a huge insect, forever transcending the determinism to which he was subjected. But if desire is a becoming, is it always ours to keep? Prem Sahib doesn’t seem to think so.