Roxana Marcoci: Your work came of age in the post-1968 period marked by student uprisings all over Europe, not least in the universities of Yugoslavia, when artists broke free from mainstream institutional settings and laid the ground for a form of praxis antipodal to official modernist culture. This alternative art was known as the New Art Practice, and its arrival signaled the peak of neo-avant-garde activities in East-Central Europe. In what ways did the New Art Practice transform the discursive relationship between art, politics and social change in the contemporary world?

Sanja Iveković: Conceptual art of the late ’60s and ’70s from ex-socialist European countries is often attributed — in critical discourse and modes of presentation — with a dissident orientation. Our Yugoslavian experience was different. New Art Practice, as critics called the art made in Yugoslavia in the ’70s, was mostly happening in student cultural centers, but occasionally it also took place in prestigious state galleries, such as the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, which featured exhibition programs of the local and international avant-garde. Although conceptual art was marginalized (student cultural centers were places fostering the practice of an “alternative activity”), this practice cannot be defined as dissident, because it was financed by the state and it was supported by a few progressive critics and intellectuals, some who were influential members of the Communist Party who held dominant political positions in art institutions and within the governmental establishment. Nor did artists position themselves as dissidents. Their critique wasn’t a “struggle against dark communist totalitarianism.” Rather, artists were more inclined to see their practice as a critique of the bureaucratic government that tried to maintain the status quo at all costs. One can rightfully say that those who were active on the counter-cultural scene at the time took the socialist project far more seriously than the cynical governing political elite.

New Art Practice was really new insofar it posed radical questions about the nature and function of art itself, about the autonomy or lack thereof of the gallery-museum context, about the influence of market logic on the production of artwork, etc. It’s true that all of this was also present on the agenda of artists working in the West, but it seemed to us that the idea of the artwork’s dematerialization and generally of art that leaves the institutions to communicate with “the people” was much closer to the socialist model of society.

RM: “Sanja Iveković: Sweet Violence” on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, is your first retrospective in the United States. The exhibition’s title derives from your earliest work included in it, Sweet Violence (1974), a video piece that addresses the corrosive effect of media culture under the state doctrine known as the Third Way. This was a political experiment that took place during Marshal Tito’s rule, which was defined by an idiosyncratic mix of socialist revolution and free-market economics (Marx and Coca-Cola), steeped in propaganda. Could you say a few words about this piece and your intention in making it to overlay black strips on a television monitor to videotape Zagreb’s daily propaganda program? Was your intention to visually disconnect viewers from the “sweet violence” of media seduction?

SI: In the early ’70s I made a number of videos focusing on the institution of television. At the time there was no video equipment available to artists. The promise of the “3/4-inch revolution” coming from USA sounded quite strange to us. The idea that television is a powerful tool that can “sell” not only a president to his country but also something else, for instance, education, or critical judgment, was for a while supported by Zagreb intellectuals who were enthusiastic about the socialist society. Yet, their voices were not heard. I found the text by Guido Guarda, the Italian media critic who first employed the term “dolce violenza,” and I used it as the title of my video. Placing black tapes over the TV screen while recording the “Economic Propaganda Program” was the simplest and most effective way to disconnect viewers from the “sweet violence” of media culture — violence committed in a tender, endearing way and thus being even more efficient in its damaging effect.

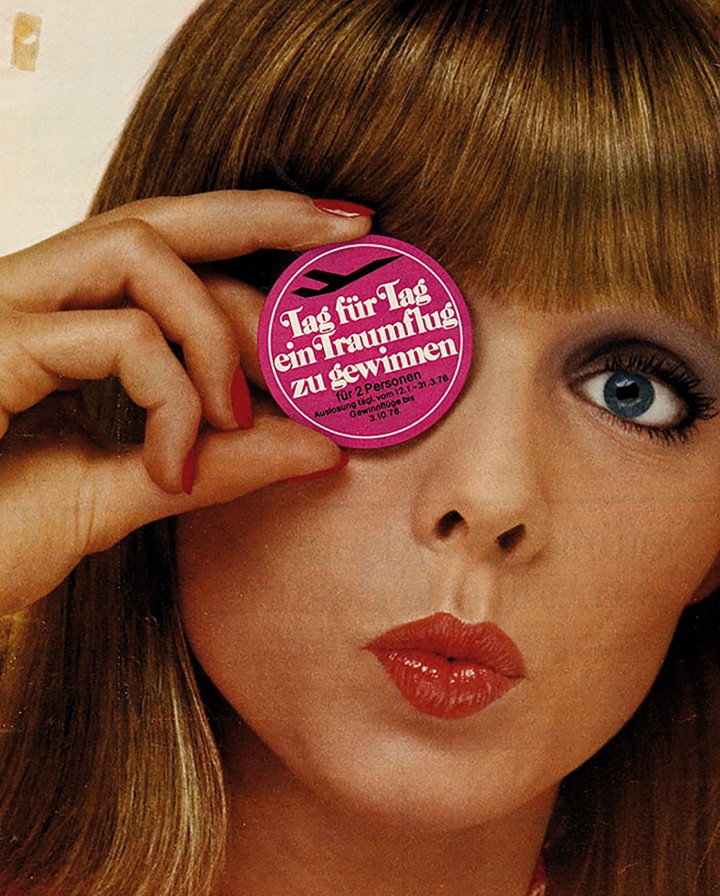

RM: Other works from the mid ’70s, such as Double Life (1975-1976) and Tragedy of a Venus,(1975) address the media’s role in identity formation. How did these influential photomontages enact the feminist shifts that have been at play in your work?

SI: In Double Life I juxtaposed the advertisements I found in women’s magazines (mainly imported from the West) with photographs of myself taken from my private albums. Since the pictures of myself predate the advertisements taken from mass media, it is clear that I did not mimic or re-enact the models’ body postures and gestures, although the similarities are quite striking. I wanted to show the power of mass media not only in the identity construction of some intangible women but also to analyze my own personal role as a woman in society, and specifically in a society in which — in spite of its officially egalitarian policy — patriarchal culture was still very much present and alive, and in which the consumerist dream was a part of everyday life. Double Life, Tragedy of a Venus, and other early photomontages were shown in 1976 in my first large-scale museum exhibition in Zagreb. In 1979, the first international feminist conference took place in the Student Culture Centre in Belgrade. It was the first conference on this topic to take place in a socialist country. Although at the time I had the chance to see some feminist art in foreign magazines and at one exhibition in Graz, the fact that I was able to listen to and read our feminists was extremely empowering to me.

RM: In 1979 you engaged in an act of political defiance when you performed Triangle on the balcony of your apartment during one of Marshal Tito’s official visits to Zagreb. What did it mean to you as a woman and as a feminist artist to confront the cult of the leader and the state’s system of political surveillance?

SI: The important advantage of living and working in socialism is that you learn very early on that nothing is independent from ideology. Everything we do has a political charge, and the division between politics and aesthetics is entirely erroneous. I have repeatedly asked myself what is my position in the social system, my relationship with the system of power, domination and exploitation, and how can I respond and act meaningfully as an artist. The political and activist attitude is the result of this dilemma: I want to be deliberately active rather than a passive “object” of the ideological system. In Triangle I played my own politics of display against the state’s politics of display.

RM: The decade of the ’80s was bracketed by two historic events: Marshal Tito’s death in 1980 and the dismantling of the Berlin Wall in 1989, which began the splintering of the communist bloc in East-Central Europe and the intensification of nationalist movements among federations in Yugoslavia. In Croatia, the political paradigm changed with the election of the Social Democrats in 2000. However, the switch from communism to postcommunism resulted in the formation of a consumerist society with little recollection of its past. Would you comment on Gen XX (1997-2001), and on the question of historical memory?

SI: My aim in making Gen XX was to articulate my own act of resistance at a moment when Croatia was infected with nationalist ideology in its fight against the so-called leftist cultural hegemony. Gen XX was conceived not for a gallery. I wanted to find a context that would be broader than just that of art. Therefore, I made it as artist’s pages for Arkzine, an alternative magazine, which at the time was the only publication in Croatia open to national and international theoreticians and activists fostering a critical discourse. My target audience was the younger generation, which explains why I found it appropriate to use images of fashion models in advertisements for Dior, Chanel, Armani and others. I erased the logos of companies and replaced them with the names of women partisans who fought in the antifascist resistance movement during the socialist revolution, heroines well known to my generation but unknown to the generation that came of age in the ’90s.

RM: Many of your recent works, such as Lady Rosa of Luxembourg (2001/2011), Women’s House (Sunglasses) (2002-ongoing) and Report on CEDAW U.S.A. (2011), expose the disregard for women’s rights that today pervades both transitional societies and democracies that pretend otherwise. What do you consider to be the most effective way of engagement in activist artistic practice?

SI: My works are formally very diverse because I always seek the most effective way of getting the message across in a given context. I think that this state of urgency, which is a characteristic of the times we live in, demands that artists be extremely flexible; strategies of intervention (as opposed to an individual style, the auratic and the idea of artist as genius) form the feminist heritage, which is exceptionally relevant to today’s artistic practices. I try to figure out a mode of dealing with art in a political way. Instead of involving myself in traditional politically engaged art, I propose political engagement in artistic practice. I like to collaborate with nongovernmental and women organizations. I am convinced that activism and art can be mutually complementary.